Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Colombiana de Ciencias Pecuarias

Print version ISSN 0120-0690

Rev Colom Cienc Pecua vol.25 no.4 Medellín Oct./Dec. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Forage intake of the collared peccary (Pecari tajacu)¤

Consumo de forraje del pecarí de collar (Pecari tajacu)

O consumo de forragem pelo cateto (Pecari tajacu)

Rubén C Montes Pérez1*, Biol, Dr; Odeisi Mora Camacho2, MVZ; José M Mukul Yerves1, MVZ, MSc.

1 Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán;

2 Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia.

* Corresponding author: Rubén C Montes Pérez. Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. Apartado Postal 4-116. Itzimna. CP. 97100. Mérida, Yucatán, México. Email: mperez@uady.mx

(Received: 24 june, 2011; accepted: 15 may, 2012)

Summary

Objective: to evaluate voluntary intake of four forage species by collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) under confinement. Methods: four peccaries underwent a consumption test to assess their preference among four forages (Leucaena leucocephala, Guazuma ulmifolia, Brosimum alicastrum and Pennisetum purpureum). The experiment was divided into two phases. The first consisted of an adaptation period of 4 days during which they were offered 1 kg of each forage in different feeders for 4 hours, then removing and weighing the remaining forage to determine consumption. The voluntary intake test was assessed in the second phase using a Latin square design (4x4). Forage intake was analyzed using the Statgraphics 5.1 software. Results: highly significant differences (p <0.01) between consumption of each forage were observed, being G. ulmifolia the most consumed (170.18 g dry matter), followed by L. leucocephala, and B. alicastrum (132.19 and 98.37 g dry matter, respectively). The least consumed was P. purpureum (21.65 g dry matter). Conclusions: considering its high consumption and moisture content, G. ulmifolia could be successfully used as cut fodder for peccaries under confinement.

Key words: confinement, native fodder, peccaries, voluntary intake.

Resumen

Objetivo: evaluar el consumo voluntario de cuatro especies de plantas forrajeras por el pecarí de collar bajo confinamiento (Pecari tajacu). Métodos: cuatro pecaríes fueron sometidos a una prueba de consumo en cautiverio para evaluar su preferencia entre cuatro sustratos forrajeros (Leucaena leucocephala, Guazuma ulmifolia, Brosimum alicastrum y Pennisetum purpureum). El experimento se dividió en dos fases. La primera consistió en un periodo de adaptación de 4 días, durante los cuales se les ofreció 1 kg de cada forraje en diferentes comederos durante 4 horas, retirando luego el forraje y pesando el remanente para determinar su consumo. La prueba de consumo voluntario se ejecutó en la segunda fase mediante un diseño de cuadrado latino (4x4). El consumo de forraje se analizó mediante el software Statgraphics 5.1. Resultados: se encontraron diferencias altamente significativas (p<0.01) entre los consumos de cada forraje, siendo G. ulmifolia el más consumido (170.179 g materia seca), seguido de L. leucocephala, y B. alicastrum (132.19 y 98.37 g de materia seca, respectivamente), siendo P. purpureum el menos consumido (21.65g materia seca). Conclusiones: por su alto consumo y gran contenido de humedad, G. ulmifolia podría utilizarse exitosamente como forraje cortado para pecaríes bajo confinamiento.

Palabras clave: consumo voluntario, forraje nativo, pecaríes, zoocriadero.

Resumo

Objetivo: avaliar o consumo voluntário de quatro espécies de plantas forrageiras pelos catetos sob confinamento (Pecari tajacu). Métodos: quatro catetos foram submetidos a uma prova de consumo em cativeiro para avaliar sua preferência entre quatro substratos forrageiros (Leucaena leucocephala, Guazuma ulmifolia, Brosimum alicastrum e Pennisetum purpureum). O experimento dividiu-se em duas fases. A primeira consistiu num período de adaptação de 4 dias, durante os quais foi oferecido 1 kg de cada forragem em diferentes comedouros durante 4 horas, retirando depois a forragem e pesando o remanente para determinar o consumo. A prova de consumo voluntário executou-se na segunda fase mediante um desenho de quadrado latino (4x4). O consumo de forragem analisou-se mediante o software Statgraphics 5.1. Resultados: Foram encontradas diferenças altamente significativas (P <0.01) entre o consumo de cada forragem, sendo G. ulmifolia o mais consumido (170.179 g de matéria seca), seguido por L. leucocephala e B. alicastrum (132.19 e 98.37 g de matéria seca, respectivamente), e P. purpureum o menos consumido (matéria seca 21.65g). Conclusões: Devido ao consumo elevado e ao alto teor de umidade, G. ulmifolia poderia ser utilizado com sucesso como forragem cortado para catetos em confinamento.

Palavras chave: catetos, consumo voluntário, forragem nativa, zoo-criadouro.

Introduction

The digestive tract of the collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) is anatomically and physiologically similar to ruminants, as it has three compartments in the stomach: one on the left side, one intermediate, and one on the right side. The left side has two diverticula where fiber fermentation occurs. The intermediate compartment leads to the esophagus. The right compartment shows glandular and nonglandular regions similar to monogastric animals. Given the above, it is assumed that this species has an intermediate digestive physiology resembling traits of both polygastric and monogastric animals (Gisela et al., 2003).

The nutritional requirements of collared peccaries have been studied by Zervanos (1972), who reported that the digestible energy requirement of the peccary is 198 kcal / day / kg of metabolic weight during winter and 153 kcal / day / kg of metabolic weight during summer. Carl and Brown (1985) mentioned that the peccary requires 6.8% crude protein to meet its maintenance requirements, while Sowls (1997) reported that it requires 10 to 15% dietary crude protein for growth.

Some studies suggest that domesticated herbivorous species such as the collared peccary have the ability to select their food based on the energy and protein content of the diet. These animals tend to maximize or minimize their intake of these nutrients according to their needs and the concentration of anti-nutritional substances (Cassini, 1994).

There is little information about the collared peccary's preference of native forages, which is important when formulating diets that include local and readily available feedstuffs (Mukul, 2003; Montes, 2005).

Based on the above, the objective of this study was to evaluate preferences among several fodder plant species (Leucaena leucocephala, Guazuma ulmifolia, Brosimum alicastrum, and Penisetum purpureum) as a feed source for collared peccaries (P. tajacu) in captivity.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the Xmatkuil Management and Wildlife Conservation Unit, Municipality of Merida, Yucatan, Mexico. The Unit is located 10 meters above sea level at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of the Autonomous University of Yucatan. The region's climate is subhumid tropical, with rains in the summer, according to Köppen Awoig climate classification modified by Garcia (1988). The maximum temperature varies between 35 and 40 °C and the average annual temperature is 27 °C. The relative humidity varies from 65 to 90% (average 80%) and annual rainfall is 935.5 mm. There are two seasons: rainy (June to November) and dry (December to May) (Garcia, 1988).

Four unneutered, adult male collared peccaries (P. tajacu) were used. Their average weight was 20 ± 1.8 kg. The animals were housed in a 100 m2 pen. The pen had a tin roof, feeders, drinking water supply, and a pond.

The experiment was divided into two stages. The first phase was an adjustment period. At this stage the animals were weighed and identified with ear tags. Subsequently, four 60 x 40 cm feeders were placed in the pen. Each feeder contained one of the substrates under evaluation: Huaxin (L. leucocephala), Pixoy (G. ulmifolia), Ramon (B. alicastrum), or Taiwan grass (P. purpureum). Feed was placed in the pen for 3 to 4 hours. Subsequently, rejected feed was removed and weighed to determine the amount of dry matter intake. Following this, a basal diet was offered. This diet consisted of pumpkin (Cucurbita sp), papaya (Carica papaya), cabbage (Brassica oleracea), chayote (S. edule), and commercial pig-feed (Lorgam, Mexico) with 9.5% crude protein. This process was repeated during the four-day adaptation period.

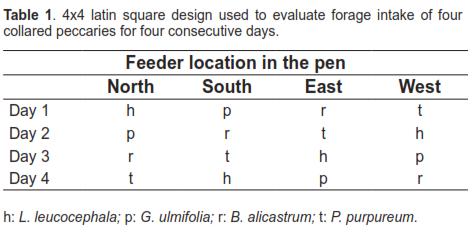

During the second stage the same individuals were used in a 4x4 latin square design with two replicates. The treatments corresponded to each of the four substrates: L. leucocephala (h), G. ulmifolia (p), B. alicastrum (r) and P. purpureum (t), which were randomly placed in the North, South, East, or West position for four consecutive days, respectively. The location of fodders was changed according to the Latin square design shown in table 1.

Estimation of dry matter content of the feed was conducted according to the report by Castillo et al. (2009). Forage intake was estimated from the difference between dry matter offered and rejected in each treatment. The sources of variation for the variance analysis were days, feeder location, replicate, and forage. The multiple means comparisons were conducted with the Tukey test (Steel and Torrie, 1985). The Statgraphics 5.1 software was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

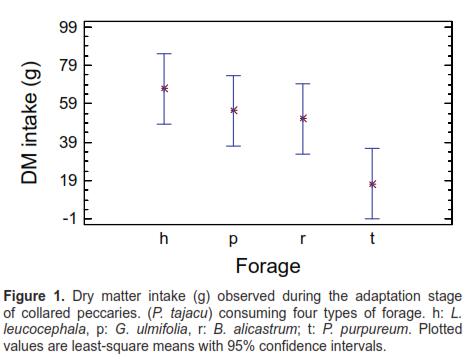

Forage dry matter intake during the adaptation phase is shown in figure 1.

Table 2 shows means and standard errors of dry matter intake for the tested forage during the adaptation phase and the statistical differences between them.

Differences in forage intake were detected during the second stage. Intake was highest for Pixoy (G. ulmifolia) and lowest for Taiwan grass (P. purpureum), as shown in figure 2.

Analysis of variance showed highly significant differences for dry matter intake between treatments (P <0.01). The multiple means comparison showed that G. ulmifolia forage was the most consumed, followed by L. leucocephala and B. alicastrum, while P. purpureum was consumed the least. These results are shown in table 3.

Discussion

Mean dry matter intake of B. alicastrum, G. ulmifolia, and L. leucocephala showed no significant differences during the adaptation stage. There was only a difference between the last two and P. purpureum. Dry matter intakes were relatively lower than those recorded in the second stage. Given the short period of time in which forage was offered, these results were expected for this stage. Moreover, at this stage the aim was not to evaluate forage preference but introducing the feed substrates to the animals prior to the second stage, as recommended in related studies (Garcia et al., 2008a; Garcia et al. 2008b). In the second stage, the Latin square design lasted four days, with periods of four hours each, replicated twice, with significant differences at 1%. This is consistent with the statistical inference principle, which states that design accuracy improves by increasing the number of replicas, allowing the detection of significant differences in the response variables (Wackerly et al., 2002).

In the second stage, intake differences were observed for two occasions of tree foraging. The Ramon (B. alicastrum) as Huaxin (L. leucocephala) and Pixoy (G. ulmifolia) are native forage that have been traditionally used for feeding cattle and pigs in Yucatan (Acosta et al., 1998). However, they are not widely used in commercial livestock operations. Despite this, they have high amounts of crude protein and condensed tannins in comparison to Taiwan grass (P. purpureum). Table 4 shows some characteristics of the tree forage tested in this study.

G. ulmifolia has relatively high moisture content (34.98%) compared to B. alicastrum (10%) and L. leucocephala (3.3%) (Medina, 2000). It is therefore expected to retain moisture for longer periods of time, which is an advantage due to the high temperature conditions in the area where water loss is significant when cut forage is offered. These characteristics could explain why G. ulmifolia forage was most preferred by peccaries. These results are in agreement with studies by Martinez- Romero and Mandujano (1995), and Garcia et al. (1992), who reported that the peccary eats mostly leaves and branches of B. alicastrum during most of the year, and fruits of G. ulmifolia in the fruiting season.

Possible causes for the increased intake of native forage compared with P. purpureum are the relatively high content of crude protein and the amount of condensed tannins. Castillo et al. (2009) reported that there is a positive linear relationship between amount of crude protein and condensed tannins with dry matter intake of four types of forage tested for white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Although the collared peccary seems to be monogastric, its stomach produces volatile fatty acids (VFA), such as acetic, propionic, and butyric, in amounts similar to bovines fed ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum). For this reason, the peccary has been considered a pseudo-ruminant (Sowls, 1997). It is therefore possible that peccaries have an intermediary metabolism similar to that of ruminants. Oliveira et al. (2009) indicated that P. tajacu is able to use urea added to diets based on corn, soybean, and Taiwan grass (P. purpureum). They reported greater weight for the animals fed urea compared with the control group (23.25 vs 22.08 kg, respectively).

The forage protein and dry matter content may not be a limiting factor as peccaries have low protein requirements (6.8%) in desert climates and prairies of Texas (Carl and Brown, 1985). Arboreal substrates offered in this evaluation had crude protein (CP) levels exceeding the requirements, except for Taiwan grass, which has minimal. This suggests that native tree forage, rather than being a basal diet food, can be given as a supplement to the animals daily diet. Lopez et al. (2006) note that under free-living conditions the whitelipped peccaries (Tayassu peccary) are capable of consuming a wide variety of foliage and fruit in the rainforest of Costa Rica. The annual average of crude protein thereof is 7.8%. During the rainy season, when the feed supply is greater and higher CP levels exist, peccaries reproduction increases and lactation improves. This is the case of B. costaricensis (15.9%) and Ficus sp (16.2%), indicating that the Tayassuidae family is highly adapted and resilient to changes of the floristic composition of its habitat.

Therefore, the diet formulation for confined peccaries could be based on low-cost and nutritionally adequate fruits, supplementing protein with native forage such as those mentioned here. This allows the producer to obtain crude protein at a lower cost than that offered by the balanced products in the market. Another advantage is that seeds of this native forage are readily available and very drought resistant. Taiwan grass would be less useful since it requires an adequate irrigation system to ensure optimal growth (Espinoza et al., 2001). The forage yield (biomass per hectare) and growth in order from highest to lowest is L. leucocephala, G. ulmifolia, and B. alicastrum. The latter requires a period of 3-4 years to reach optimum performance (Monforte, 2002).

References

1. Acosta BLE, Flores GJS, Gómez PA. Uso y manejo de plantas forrajeras para cría de animales dentro del solar en una comunidad maya en Yucatán. Etnoflora Yucatanense, Fascículo 14. Yucatán México: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán; 1998. [ Links ]

2. Carl GR, Brown DR. Protein requirements of adult collared peccaries. J Wild Manage 1985; 49:351-355. [ Links ]

3. Cassini M. Behavorial mechanisms of selection of diet components and their ecological implications in herbivorous mammals. J Mamm 1994; 75:733-740. [ Links ]

4. Castillo LFI, Montes PRC, Rodríguez MCE. Preferencias de consumo de cuatro forrajes por venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) mantenidos en cautiverio en Yucatán. Ciencia y Agricultura 2009; 7:75-82. [ Links ]

5. Chacon HPA, Vargas RCF. Digestibilidad y calidad del Pennisetum purpureum cv. King grass a tres edades de rebrote. Agronomía Mesoamericana 2009; 20:399-408. [ Links ]

6. Espinoza F, Argenti P, Gil J, León L, Perdomo E. Evaluación del pasto King grass (Pennisetum purpureum cv. King grass) en asociación con leguminosas forrajeras. Zootecnia Trop 2001; 19:59-71. [ Links ]

7. García SCLC, Castañeda MA, Santillán AS. Requerimientos de hábitat y estudio preliminar sobre los hábitos de alimentación del pecarí de collar (Dicotyles tajacu) en condiciones de semicautiverio en el estado de Yucatán. En: Memorias del X Simposio sobre Fauna Silvestre ''Gral. MV. Manuel Valtierra''. México: UNAM y Gobierno del estado de Guerrero; 1992:271- 281. [ Links ]

8. García E. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen. 4a edición. México, D.F: Instituto de Geografía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; 1988. [ Links ]

9. García DE, Medina GM, Clavero T, Humbría J, Baldizan A, Domínguez C. Preferencia de árboles forrajeros por cabras en la zona baja de los andes venezolanos. Rev Cientif FCV-LUZ 2008a; XVIII: 549-555. [ Links ]

10. García DE, Medina MG, Cova LJ, Humbría J, Torres A, Moratinos P. Preferencia caprina por especies forrajeras con amplia distribución en el estado Trujillo, Venezuela. Arch Zootec 2008b; 57:403-413. [ Links ]

11. Giraldo A. Potencial del guácimo (Guazuma ulmifolia) en sistemas silvopastoriles. En: Memorias de la Conferencia Electrónica Agroforestería para la Producción Animal en América Latina. Sánchez MD y Rosales M, editores. Roma: Estudio FAO Producción y Sanidad Animal, 1999. p. 295-308. [ Links ]

12. Gisela C, García C, Leal LM. Morfología del estómago e intestino grueso del báquiro de collar (Tayassu tajacu). Vet Trop 2003; 28:117-134. [ Links ]

13. López TM, Altrichter M, Sáenz J, Eduarte E. Valor nutricional de los alimentos de Tayassu pecari (Artiodactyla: Tayassuidae) en el Parque Nacional Corcovado, Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop 2006; 54:687-700. [ Links ]

14. Martínez-Romero LE, Mandujano S. Hábitos alimenticios del pecarí de collar (Pecari tajacu) en un bosque tropical caducifolio de Jalisco, México. Acta Zool Mex (n.s.) 1995; 64:1-20. [ Links ]

15. Medina PA. Evaluación agronómica de cinco especies de árboles forrajeros en la zona henequenera de Yucatán. Tesis profesional. Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, Mérida. 2000. [ Links ]

16. Monforte C. Efecto de la carga animal y la suplementación con follaje de Leucaena sobre los cambios de peso vivo y el comportamiento reproductivo de vacas cruzadas (Bos taurus x Bos indicus) en la zona centro del estado de Yucatán. Tesis profesional. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida; 2002. [ Links ]

17. Montes PRC. Manual para la crianza del kitam o pecarí de collar (Pecari tajacu) en corral. Mérida, Yucatán, México: Consejo Editorial de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán; 2005. [ Links ]

18. Mukul YJM. Algunas variables fisiológicas y cambios de peso en pecaríes de collar (Pecari tajacu) alimentados con dietas de maíz, ramón y calabaza. Tesis profesional. Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida; 2003. [ Links ]

19. Oliveira EG, Santos ACF, Días JCT, Rezende RP, Nogueira- Filho SLG, Gross E. The influence of urea feeding on the bacterial and archaeal community in the forestomach of collared peccary (Artiodactyla, tayassuidae). J Appl Microbiol 2009; 107:1711-1718. [ Links ]

20. Plata FX, Ebergeny S, Resendiz JL, Villarreal O, Bárcena R, Viccon JA, Mendoza GD. Palatabilidad y composición química de alimentos consumidos en cautiverio por el venado cola blanca de Yucatán (Odocoileus virginianus yucatanensis). Arc Med Vet 2009; 41:123-129 [ Links ]

21. Santos RRH, Abreu ESJ. Evaluación nutricia de la Leucaena leucocephala y del Brosimum alicastrum y su empleo en la alimentación en cerdos. Vet Mex 1995, 26:1. [ Links ]

22. Sowls L. Javelinas and other Peccaries their biology, management, and use. Tucson Arizona: Texas A & M University press college station;1997. [ Links ]

23. Steel GDR, Torrie HJ. Bioestadística: Principios y Procedimientos. 2a ed. (1a ed. en español). Bogotá: McGraw- Hill Latinoamericana; 1985. [ Links ]

24. Tropfeed (Tropical feeds). Version 3.1 Software developing by Oxford Computer Journals. Rome: FAO; 1992. [ Links ]

25. Wackerly DD, Mendenhall III W, Scheaffer RL. Estadística matemática con aplicaciones. 6a ed. México D.F.: Thomson. 2002. [ Links ]

26. Zervanos SM. Thermoregulation and water relations of the collared peccary (Tayassu tajacu). Doctor of Philosophy Thesis. Arizona State University, Tempe. 1972. [ Links ]

Notas al pie

¤ To cite this article: Montes RC, Mora O, Mukul JM. Forage Intake of the Collared peccary (Pecari tajacu). Rev Colomb Cienc Pecu 2012; 25:586-591.