Introduction

Based on archeological evidence, water buffaloes were domesticated in Iran from 2500 BC (Naserian and Saremi, 2007). Buffaloes adaptability to low quality grasses, high temperature and humidity, irregular rainfall, disease resistance along with having a long productive life made them the first option as domestic animals for providing milk and meat in Iran (Dezfuli et al., 2011). In comparison to cow milk, Khuzestan buffalo milk has more fat (6.6%) and solid content (Borghese and Mazzi, 2005). This prominent benefit of Khuzestan buffalo can compensate for the low fat percentage of Iranian Holstein dairy cows (Eghbalsaied et al., 2016), and is the subject of growing attention in the Iranian dairy market.

Several studies have been conducted to identify the major genes responsible for milk production and composition in dairy cows (Komisarek and Dorynek, 2009; Pasandideh et al., 2015). The polymorphism in growth hormone (GH) was associated with selection for milk fat production in Red Danish and Norwegian Red cattle (Høj et al., 1993). It controls energy metabolism in high-yield cows (Hart et al., 1978), affects the size of mammary tissue (Capuco and Akers, 2009), reduces the apoptosis rate of the mammary cells (Accorsi et al., 2002), and consequently increases milk production (Yao et al., 1996). The growth hormone receptor (GHR) can also affect milk and fat yield of dairy cows (Jiang and Lucy, 2001; Viitala et al., 2006). Growth hormone- releasing hormone receptor (GHRHR) is secreted by the hypothalamus and stimulates the release of pituitary growth hormones (Godfrey et al., 1993). Besides these genes, a number of miscellaneous genes are involved in milk yield and milk contents. Among them, pituitary-specific transcription factor-1 (Pit1), also known as POU domain-class 1 transcription factor 1 (POU1F1) and Kappa-Casein (KCN3) are important genes involved in milk quality (Erwin et al., 1983; Fries et al., 1993; Lien and Rogne, 1993).

Although the importance of the above-mentioned genes has been well documented in dairy cows, there are limited publications on their role in buffaloes. Therefore, providing the genetic polymorphism of these candidate genes is essential for devising an integrated breeding plan for water buffalos. The goal of the present study was to assess the effect of genetic polymorphisms in GH, Pit-1, GHR, GHRHR, and KCN3 genes on milk production and body weight of water buffaloes in Khuzestan province, Iran.

Material and methods

Ethical considerations

The method for blood sampling was approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Isfahan Islamic Azad University, April 2014 (Nr. 15021393).

Animals and location

Blood samples were collected from 60 buffaloes from the Ahvaz (31°19′13″N 48°40′09″E) and Dezful (32°22′57″N 48°24′07″E) districts in the Khuzestan province, Iran. The buffaloes were 4 to 15 years old. Based on twice daily milking, animals were divided into low-yielding (<10 kg) and high- yielding (>13 kg) dairy buffaloes. In addition, based on their body weight, buffaloes were classified into three categories: light (<450 kg), moderate (450-500 kg), and heavy (>550 kg). Breeding and feeding conditions were similar in the rural riverine production for all animals.

DNA was extracted from blood samples using a SinaClon kit, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out for amplification of GH, GHR, GHRHR, Pit1, and KCN3 genes using the specific primer sequences (Table 1) (Moody et al., 1995; Woollard et al., 1994); (Andreas et al., 2010); (Balogh et al., 2009); (Kalashnikova et al., 2009). Amplification of segments of interest (Table 1) was performed in 20 µl reaction volume containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 5 µM of each primer pairs, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 10X PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1.5 units of Taq DNA polymerase (SinaClon, Iran). The PCR program for amplification of the desired targets was as follows: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 minutes, 35 cycles comprising 94 °C for 50 seconds, 62, 53, and 53 °C (for GH, GHR, and GHRHR, respectively) for 50 seconds, and 72 °C for 50 seconds, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 7 minutes. Then, the PCR product of GH and GHR genes underwent digestion with AluI, while GHRHR amplicon was digested with HaeIII restriction enzyme (Maga et al., 2006). In addition, Pit1 and KCN3 amplicons were digested with HinfI and HindIII, respectively. Samples were genotyped using the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay (Table 1). Briefly, 10 µl of the PCR product was incubated with 2 IU of the corresponding restriction enzyme at 37°C for two hours. The digested products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel. In addition, the PCR products of GH and GHR from a random sample of animals were sequenced.

Statistical analysis

Genotypic and allelic frequencies were estimated using the PopGene software, Version 1.31 (Yeh et al., 1999). Genotypic and allelic frequencies were compared between classes of milk yield and body weight using a Chi-square test. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The effect of polymorphisms using PCR-RFLP on milk yield and body weight

Using the RFLP technique, genetic polymorphism was assessed in five candidate genes in relation to milk yield of Iranian water buffalo. Using the HaeIII restriction enzyme, the previously detected mutation in GHRHR (Maga et al., 2006) was not detected in the Iranian water buffaloes. Implementation of the restriction enzymes for GH, GHR, Pit1, and KCN3 resulted in detection of polymorphisms, corresponding to other studies on water buffalo around the world. Allelic frequencies of GH, GHR, Pit1, and KCN3 genes are presented in Table 2. The allelic frequencies of mutant alleles for GH/AluI, GHR/AluI, KCN3/ HindIII, and Pit1/HinfI were 47.5, 74.2, 49.2, and 51.7%, respectively.

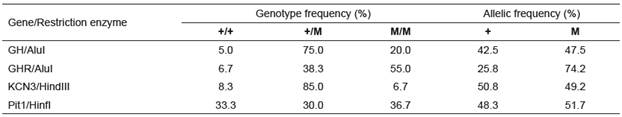

Table 2 Allelic and genotypic frequencies of GH/AluI, GHR/AluI, KCN3/HindIII, and Pit1/HinfI in Khuzestan water buffaloes.

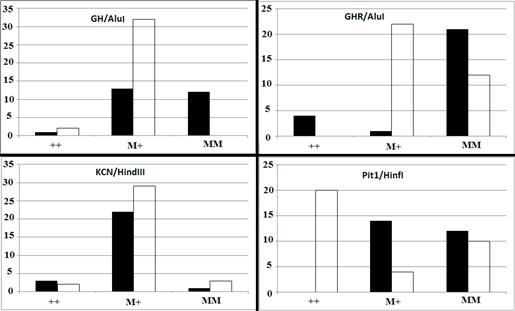

There was a significant difference in GH/AluI genotypic frequency between high and low milk-yielding buffalos (p<0.0001). Frequency of the wild type allele was higher in the low-yielding group, while the mutant allele was more abundant in the high-yielding group (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Genotypic distribution of GH/AluI (p<0.0001), GHR/AluI, KCN3/HindIII (p=0.5729), and Pit1/HinfI (p<0.0001) in two classes of high- (black bar) and low-yielding (white bar) Khuzestan water buffalo. M and + indicate mutant and wild type alleles, respectively.

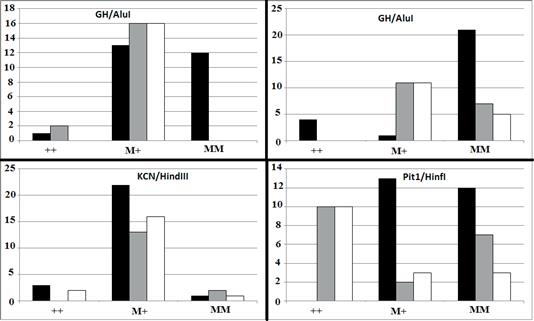

Also, there was a significant difference in genotypic frequency of GH between body weight classes (p=0.0002) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Genotypic distribution of GH/AluI (p=0.0002), GHR/AluI (p<0.0001), KCN3/HindIII (p=0.5489), and Pit1/HinfI (p<0.0001) in three classes of light- (black bar), moderate- (gray bar), and heavy-weight (white bar) Khuzestan water buffalo. M and + indicate mutant and wild-type alleles, respectively.

The effect of the GHR allele detected by the AluI restriction enzyme was also significantly different between high and low milk-yielding groups (p<0.0001). Although the majority of high-yielding buffaloes were homozygote for MM, all of the low- yielding buffaloes carried at least one mutant allele for the GHR/AluI restriction site. There was a significant difference in distribution of genotypic frequencies of GHR/AluI between body weight classes (p<0.0001). The majority (84.0%) of heavy-weight buffalos were homozygote mutant for GHR/AluI.

No significant difference was observed for KCN3 allelic and genotypic frequencies among either milk production or body weight classes. The effect of detected Pit1 polymorphism on milk production was statistically significant (p<0.0001). Fifty-eight percent of low-yielding buffalos were PP homozygous, while no animals from the high-yielding group were homozygous PP. In addition, Pit1/HinfI genotypic frequencies were significantly different among body weight groups (p<0.0001).

Sequencing results of GH and GHR revealed multiple SNPs in Iranian water buffalo

Results of sequencing revealed four mutations in GH and one mutation in GHR genes of Iranian water buffalos, compared to the NCBI reference sequences of NM_001290929.1 and NM_001290971.1, respectively (Figure 3). The mutations in DNA of GH correspond to G495A, C496A, and G498A conversions in the mRNA sequence. One of these mutations, C496A, was a missense mutation, which causes Q166K (Glutamine to Lysine) (Figure 3). Both the G495A and G498A were silent mutations for Lys (Lysine) and Thr (Threonine). In addition, one mutation was detected in intronic region 4, C1501T of GH. The only detected mutation in the GHR gene corresponded to the G1702T mutation in mRNA sequence, which was a silent mutation for Ile (Isoleucine) at position 561.

Discussion

Khuzestan buffalos are distributed in the tropical zone of Iran and Iraq with a population of more than 104,000 and 120,000 water buffaloes, respectively (Borghese, 2010). An average annual population growth of 2.6% has been reported in Iranian Khuzestan buffalos (Kamalzadeh et al., 2008). Defining important genes responsible for growth rate and milk yield is critical to uncover the genetic mechanism controlling these attributes in water buffalo. However, documentation is limited on the importance of these genes in water buffalo while several studies have documented the importance of growth factors on the performance of dairy cows (Bauman et al., 2015; Berry et al., 2016; Bines and Hart, 1982; Hadi et al., 2015; Machlin, 1973). Therefore, defining candidate genes that can play key roles in milk and meat production is an essential step for the genetic improvement of water buffaloes. Subsequently, identifying missense and nonsense mutations in the candidate genes can be helpful in animal genetic/genomic selection. In this study, polymorphisms in GH, GHR and GHRH as well as KCN3 and Pit1 genes in Khuzestan buffalo were investigated. The results indicated that except for GHRH, all the assessed genes using the RFLP technique were polymorphic. The mutant alleles were highly abundant in the studied population, ranging from 47.5 to 74.2% in GH and GHR, respectively. This result confirmed the findings of previous studies indicating the presence of high genetic diversity in Iranian buffalo and water buffalo (Heydarian et al., 2014; Javanmard et al., 2005; Ranjbar et al., 2016; Shokrollahi et al., 2009; Taghizadeh et al., 2014). The results of PCR-RFLP for GH/AluI and GHR/AluI genes showed that the frequency of mutant allele was 3.5% in Iraqi water buffaloes, while all animals were monomorphic for the GHR/AluI allele. No polymorphism was detected using the RFLP method for GH and GHR genes in Egyptian water buffaloes (Hussain, 2015). A study of Bangladesh water buffalos for GHRHR showed the presence of both mutant and wild type alleles (Andreas et al., 2010). All animals in the present study were monomorphic wild type for GHRHR. Our results showed that both Pit1 and KCN3 are highly polymorphic in Khuzestan buffaloes. Although the Pit1/HinfI mutation was characterized in Indian and Indonesian buffaloes (Jakaria and Noor, 2015; Parikh and Rank, 2013). Assessment of this mutation in Egyptian buffaloes showed a lack of polymorphism (Nasr et al., 2016). Moreover, KCN3/ HindIII was wild type monomorphic in Pakistani buffalo (Riaz et al., 2015). Our results indicate that local buffaloes can be substantially variable for the assessed genes. Iranian Khuzestan water buffaloes have some similarity with Iraqi Khuzestan buffaloes and may have originated from the same ancestor (Watanabe et al., 1994). However, the results of the present study showed that, unlike Iraqi water buffaloes, Iranian water buffaloes are polymorphic for GHR/AluI. Recently released data indicated the presence of high genetic diversity of African buffalo in nine African countries (Smitz et al., 2016) the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer. Therefore, the present study highlighted the importance of sequencing candidate genes in buffaloes from each specific local area to devise a proper strategy for genetic selection.

A single mutation in the Pit1 gene causes a substantial deficiency in anterior pituitary Pit-1 hormone production and subsequently an aberrant activation of GH and prolactin genes (Cohen et al., 1996). A polymorphism in Pit1 gene was associated with milk traits in Egyptian and Indian buffaloes (Othman et al., 2011; Parikh and Rank, 2013). In addition, water buffaloes carry polymorphism in the KCN gene (Cinar et al., 2015; Mitra et al., 1998), which can affect their milk yield as well as feta cheese processing parameters (Shakerian et al., 2016).

We then looked at whether the detected polymorphism was associated with milk production and body weight traits. The results indicated that the majority of buffaloes from the high-yielding group carried the mutant allele for GH, GHR, and Pit1. Moreover, the genotypic distribution of GHR and Pit1 was different between body weight classes, so that the mutant alleles were more abundant in buffaloes from the heavy weight class. The effect of GH as a metabolic modifier in livestock has been well documented (Dunshea et al., 2016 ). An association of Pit1 with milk yield in buffalo was suggested by Parikh and Rank (2013). In line with our results, a recent study on Egyptian water buffalo verified the importance of Pit1 polymorphism on milk yield and body weight (Nasr et al., 2016). Therefore, our results indicate that besides employing growth hormones on dairy farms, there is a high potential for genetically selecting and upgrading GH and Pit1 as growth factors as well GHR in dairy buffaloes. However, KCN3 polymorphism was not associated with either milk yield or body weight traits. This indicates that the mutation has not been under selection pressure either naturally or artificially for milk and meat production in Iranian water buffalo.

Finally, the PCR amplicons from GH and GHR were sequenced to see if further mutations exist in these genes. Our results showed the presence of several mutations in GH and one mutation in GHR. Among them, the C496A causes Q166K (Glutamine to Lysine) in GH polypeptide. None of these mutations have been reported in the literature. The detected mutation in GHR has not been reported in the literature and is different from the detected mutation by Shi et al. (2012). Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, no literature has been published on the association of detected mutations and milk/meat attributes of buffalo. Nonetheless, an association study with a larger sample size is yet to be explored if the detected SNPs in the present study are associated with production performance of water buffalo.

In conclusion, our results suggest that a high number of SNPs may segregate in GH and GHR genes of Iranian buffalo. It should be noted that the majority of polymorphism studies, including this study, have been based on the PCR-RFLP results from bovine genome. Results of this study provides information for one missense mutation in GH and highlighted that sequencing the candidate genes in buffaloes can be very practical to survey the prevalence and importance of possible SNPs in buffalos. These data can provide information about genetic diversity as well as association analysis of the above-mentioned genes for further application in selection programs of Khuzestan buffaloes.