Introduction

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is a nematode of the family Angiostrongylidae, within the Strongylida order. A. abstrusus is the most important nematode of the respiratory system in domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) and is distributed worldwide (Traversa and Di Cesare, 2016). A. abstrusus cause occasional infections in several wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris) from Europe (Traversa and Di Cesare, 2016), and also in serval cats (Leptailurus serval) and lions (Panthera leo) in Africa (Di Cesare et al., 2016). Infection by A. abstrusus has also been reported in South American Leopardus tigrinus, L. colocolo and in Puma yagouaroundi (Penagos-Tabares et al., 2018).

A. abstrusus is characterized by having an indirect life cycle with gastropods acting as intermediate hosts (Anderson, 2000); the L1 requires hosts such as land snails (Helix spp. and Lissachatina fulica), land slugs (Deroceras spp. or Arion spp. and Arion lusitanicus) (Jezewski et al., 2013; Valente et al., 2017) or a paratenic host such as rodents, reptiles, birds or frogs (Elsheikha et al., 2016). The A. abstrusus L3 is the infective larval stage for the definitive host (Anderson RC, 2000). The L1 penetrates snails and slugs, where they develop to L3. Once ingested, the infective L3 penetrates the intestinal mucosa of the definitive host and reaches to the lungs via lymphatics (Elsheikha et al., 2016).

Infection by A. abstrusus ranges from subclinical to severe clinical manifestations that may include abdominal breathing with an open mouth, intense coughing, sneezing, mucopurulent discharge, dyspnea, and hydrothorax. In more severe infections the animal may develop interstitial pneumonia (Traversa et al., 2008). Secondary bacterial infections can occur in severe cases, leading to death (Salamanca et al., 2003). Diagnosis is based on direct observation of the parasite in fecal samples or airway wash examination (Traversa and Di Cesare, 2016).

A. abstrusus was previously reported in domestic cats in Colombia (Penagos-Tabares et al., 2018), and more recently using the Baermann Method in cats from Antioquia, Colombia (Lopez- Osorio et al., 2021). The parasite was observed in a case using the Ritchie technique (Salamanca et al., 2003). To the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first describing pathological lesions caused by A. abstrusus infection in a wild L. tigrinus from Colombia. L. tigrinus is currently considered a vulnerable species by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/54012637/50653881, accessed on November 5, 2021).

Case presentation

Anamnesis

A wild adult L. tigrinus from the Colombian Andes (Chipaque municipality, Cundinamarca province -North Latitude 4.4425, West Longitude 74.0414) was admitted with severe polytraumatism to “Unidad de Rehabilitación y Rescate de Animales Silvestres (URRAS) of Universidad Nacional de Colombia”. The trauma was related to a car incident on the road.

Clinical findings and diagnostic aids used

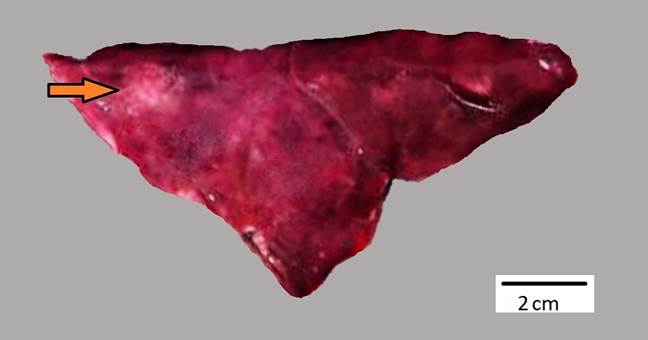

Clinical examination revealed a deep wound with partial exposure of the omentum in the ventral region of the abdomen, pneumothorax, and complete fracture of the right ilium. The feline was subjected to surgical procedures to correct the bone fracture and omentum exposure. Despite the medical efforts, the animal died six hours later. The necropsy showed poor body condition, pale mucous membranes and multiple hematomas on the ventral abdomen. The 11th and 12th ribs on the right side of the rib cage were fractured, as well as the right ilium. The lung was partially collapsed, had diffuse congestion and edema, and 2 mm white nodules randomly distributed on the visceral pleura of caudal lobes and parietal pleura of the chest wall were observed (Fig. 1). Lung tissue samples were collected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, routinely processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Figure 1 Lung of a Leopardus tigrinus naturally infected with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. Multiple white nodules of approximately 2 mm in diameter were found near the caudal region (arrow) of the lung. Moderate diffuse pulmonary edema and congestion was also present. Bar, 2 cm.

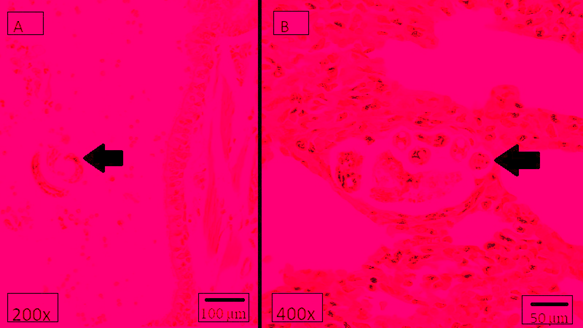

Histopathology revealed multiple coiled metastrongyloid nematode larvae in the sagittal section (80-150 μm) and cross-section (12-16 μm) within the lumen of bronchi, bronchiole and alveoli of the lung (Fig. 2). The parasites were associated with severe multifocal lymphocytic and plasmacytic interstitial pneumonia. Some macrophages and neutrophils were also present. Moderate amount of mucus, cell debris and some desquamated epithelial cells were present in the lumen of the bronchi. In addition, alveolar atelectasis, moderate multifocal hemorrhage, edema and diffuse congestion were observed.

Figure 2 Severe verminous interstitial pneumonia in a Leopardus tigrinus caused by Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. The left panel shows coiled nematode larvae (arrow) in the lumen of the bronchi. The right panel shows moderate interstitial pneumonia, characterized by a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate associated with intralesional parasitic forms (the arrow indicates a transversal portion of the nematode). H&E stain.

Following the Ritchie technique, the first step was comminution of the fecal sample, continuing with a straining with two layers of gauze. Fecal sediment was added with 10 ml of 10% formalin, allowing five minutes for fixation of parasite structures and continuing with the addition of 3 ml ether to the formalinized solution. The specimen was then centrifuged at slow speed (1500 rpm for two minutes). Ether, superficial debris and formalin were completely decanted using an applicator to free superficial debris from the centrifuge tubes. The last step consisted in coverslip preparations. The remaining sediment was mixed with the fluid and poured onto a slide. A small drop of 2% iodine solution was placed near the drop of the sediment and mixed. Finally, the coverslip was pushed into the drop (Rictchie, 1948). A. abstrusus (Railliet, 1898) L1 were identified in the sample (Fig. 3). A. abstrusus L1 in feces were 360-400 μm long (median range: 370 μm and 15-20 μm in diameter). A. abstrusus appeared as a short and thick larva with sub-terminal spine on its S-shape, with conical head and granular content. Ancylostomatidae eggs (Ancylostoma spp., Uncinaria spp.) and Capillaria spp. were also observed.

Discussion

Although A. abstrusus is routinely found in domestic cats, its presence and potential pathological effects in wild cats is mostly unknown. In this report, the necropsy of an injured and finally dead L. tigrinus and the histopathological analysis of tissue samples revealed a number of lesions associated with severe A. abstrusus larvae infection. The intralesional parasitic larvae, observed in sagittal and cross-sections, caused a moderate interstitial pneumonia characterized by lymphocyte and plasmacyte infiltration. Parasitological studies confirmed the diagnosis. Since the animal was admitted to the clinic as a case of multiple traumas, which is also the most probable cause of death, the subclinical or clinical nature of A. abstrusus larvae infection remains unknown. Both pulmonary and gastrointestinal parasitosis could contribute to a poor body condition and weakening of the animal. Polytraumatism likely occurred when the animal and a vehicle collided on a roadway, worsening the health status and ending in the death of the animal. It is also possible that the anesthesia procedure conducted in the parasitized cat may have contributed to the deadly result. In this regard, previous studies report that anesthesia procedures were associated with death in domestic cats infected with A. abstrusus (Gerdin et al., 2011).

The A. abstrusus infection caused a lymphoplasmacytic interstitial pneumonia, which has also been reported in infected domestic cats (Philbey et al., 2014) where macrophages and eosinophils are associated with the parasites. Interstitial pneumonia has been reported mainly in subacute infections (Traversa et al., 2008), while a previous study described interstitial pneumonia in experimentally infected domestic cats (Schnyder et al., 2014). Tissue damages observed in L. tigrinus in the present case are very similar to those described in fatal natural or experimental cases in domestic cats (Schnyder et al., 2014; Traversa et al., 2014). Since all available reports of A. abstrusus infection have been documented in domestic cats, it was not possible to compare the pathological lesions of L. tigrinus with other wild cats; therefore, this report constitutes the first case of A. abstrusus infection in a wild feline in Colombia.

Diagnosis of pulmonary parasitosis caused by A abstrusus larvae was established and supported by the data collected from the Ritchie technique along with the morphological characterization of the parasitic larvae. The Ritchie technique is known for increasing the likelihood of finding ova, cyst, and larvae, particularly in those specimens where they are present in insufficient numbers (Manser et al., 2016) and it is very useful in small size samples from wild animals with unknown parasitological records.

Molecular techniques such as PCR may be useful to confirm the identity of parasite species in animal tissues. Since extraction of DNA with suitable quality for PCR is not an easy procedure from formalin fixed and paraffin embedded tissues, recently, the morphological characterization of A. abstrusus and Angiostrongylus chabaudi and the location of adult nematodes was proposed as an alternative methodology to differentiate them (Wulcan et al., 2020). In addition, Giannelli and collaborators summarized the main lesions observed in different feline metastrongyloid infections and reported that A. abstrusus is usually present in respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts while Angiostrongylus mainly affects the pulmonary arteries (Giannelli et al., 2016). In the present case, no lesions were observed in blood vessels, whereas the presence of morulated eggs and larvae within the airways and alveolar ducts of the lung sections were indicative of A. abstrusus infection. Although the pathological lesions observed in L. tigrinus were mostly associated with A. abstrusus, it is important to note that the animal had a mixed parasitosis where Ancylostoma spp., Uncinaria spp., and Capillaria spp. may have also contributed to the poor body condition and was prone to traumatic coalition. In Brazil, up to 12 different parasite species in 14 fecal samples from L. tigrinus and a significant proportion of samples (35.7%) were reported positive to A. abstrusus (Kusma et al., 2015).

Large scale epidemiologic studies are limited. Research in Italy found A. abstrusus in 1.82 % (Site A) and 9.96 % (Site B) of individual fecal samples of domestic cats (total sample size: 970; Di Cesare et al., 2011). In a large European study of lungworms in domestic cats, 1990 animals were sampled, from which 613 (30.8%) were positive for at least one parasite, while 210 (10.6%) were infected with lungworms, and A. abstrusus was the species most frequently detected (78.1%) (Giannelli et al., 2017). Recently, an experimental semi-nested PCR in blood samples of 171 domestic cats in Chile found 19.9% molecular positivity (Barrios et al., 2021). In Brazil, two cases of 81 cats (2.5%) were positive for metastrongyloid L1 at the Baermann’s test, and one case was confirmed for A. abstrusus by a molecular test (Silva et al., 2021). Recently, an epidemiological study reported, for first time, the presence ofA. abstrusus, Troglostrongylus brevior, Crenosoma vulpis, and Angiostrongylus vasorumin the invasive giant African snail (L. fulica) in several locations of Colombia. A. abstrusus was found in 9.2% of L. fulica, with all positives present in a single municipality (Penagos-Tabares et al., 2019).

A. abstrusus has been reported in domestic cats in Colombia: A case in Quindío province from 121 samples processed (Echeverry et al., 2012), a case from Caquetá province (Penagos-Tabares et al., 2018), L1 was found in two cats from 473 sampled in Antioquia province using the Baermann Method (López- Osorio et al., 2021), and the parasite was observed in a case using the Ritchie technique in Bogotá (Salamanca et al., 2003). The distribution of A. abstrusus in Colombia is unknown because the parasite is limited to case reports and few studies.

Currently, the impact of A. abstrusus in wild felids is unknown. Whether unnoticed relationships between wild and domestic cats may affect the health status of domestic cats is also unknown. The absence of epidemiological information on A. abstrusus in domestic and, probably, wild cats can be explained by at least two reasons: a predominance of subclinical infections, or underdiagnosed parasitosis (Traversa et al., 2008). Feline aelurostrongylosis is distributed worldwide and is often erroneously considered to be sporadic despite being a common infection (Di Cesare et al., 2011).

The ‘dilution effect’ hypothesis suggests that the net effects of biodiversity (including host and non-host species) reduce the risk of certain diseases in ecological communities (Keesing et al., 2006). There is evidence of this effect on parasites ecology (Civitello et al., 2015). Predators can induce trait-mediated indirect effects (TMIEs) on parasites and vice versa, and these effects could have important implications for disease emergence and parasite regulation (Raffel et al., 2008). Understanding the influence of predation on parasite transmission requires explicit examination of the host, parasite, and environmental conditions that influence parasite vulnerability (Orlofske et al., 2015). The role of intermediate or paratenic host in the ecology of A. abstrusus is not fully understood. This knowledge is highly relevant for a mega-diverse country such as Colombia.

Reports of A. abstrusus infection in wild felids diagnosed either by examining fecal samples or histopathology are very limited. Being the first report of lungworms in a wild felid from Colombia, this study warns about lungworm infection of wild cats and its potential impact on animal health and wildlife conservation.