Introduction

The specific terminology for marriage, expressed by derivatives of the root γαμος,1 occurs 57 times in the nt2. In the nt literature where this terminology is found, Hebrews is the only book with one single occurrence (see Heb 13:4)3. While the importance of a concept in a book cannot be determined solely on the basis of the frequency of its specific terminology, a single occurrence of a concept does raise the interesting question on how this concept is connected with the ideas explored in the book. Generally speaking, when a notion appears several times in a document, the association of this notion with the conceptual contours of the document tends to be more evident in the text, since there are more possibilities of explicit explanations of such connection or clues that implicitly point to a connection. Conversely, less occurrences of a notion may imply fewer opportunities for the articulation of its connection with the points argued in the document. In cases of only one occurrence, conceptual connections may not even exist, as the notion may be an isolated idea merely mentioned along with other ideas.

With this perspective in mind, there is a fundamental question to be pursued in this article: is it possible to discern connections between the concept of marriage and the ideas developed in Hebrews? If so, how is marriage conceptualized in the theology of Hebrews? In order to pursue this question, I will engage in a theological reading of Heb 12:28-13:6. As it will become evident in my discussion below, 12:28-29 is part of the conceptual climax of the theology of Hebrews articulated until chapter 12, and is also a transition for the hortatory material found in chapter 13. Therefore, since in this article I will not be able to cover the entire theology of Hebrews, I will focus on how 12:28-29 provides a theological framework, which draws from the concepts developed up to that point, for the exhortations that are delineated at the end of the book. With this framework in mind, I will move to 13:1-6, the immediate context where marriage is mentioned. After hearing the theological tone of 12:28-29 (step 1) and observing the basic structure and ideas of 13:1-6 (step 2), I will concentrate on the reading of 13:4, the exhortation about marriage (step 3). After these 3 steps, it would be possible to conclude whether and (if so) how the concept of marriage is connected with the ideas developed in Hebrews. According to this plan, I will begin the reading of 12:28-29.

1. The Transition to Chapter 13 - 12:28-29 Sets the Theological Tone

A potential obstacle for the connection of the concept of marriage with the ideas explored in Hebrews is related to its location in the book. More precisely, due to differences in terms of vocabulary, form, and style, there is a trend in Hebrews scholarship that argues for a discontinuity between chapter 13 (where marriage is mentioned in v. 4) and the previous chapters of Hebrews, with the implication that chapter 13 would be «a series of miscellaneous exhortations»4. The most recent study focused on the differences of chapter 13 and Heb 1-12 is probably an article written by A. J. M. Wedderburn5. In this article, he firstly highlights differences in terms of arguments and style. According to him, while 12:25-29 is the climax of the arguments developed in chapters 1-12, chapter 13 is «a series of miscellaneous exhortations»6. Furthermore, in contrast to the style of chapters 1-12, chapter 13 is «tersely formulated, almost staccato in its string of direct or implied exhortations and commands»7. Secondly, Wedderburn underlines differences regarding vocabulary. He provides lists of words in chapter 13 that appear for the first time in Hebrews, words in chapters 1-12 that do not appear in chapter 13, and words in chapter 13 that are not found in chapters 1-12 but that are synonymous of terms that appear in chapters 1-128. At the same time, Wedderburn recognizes points of contact between chapters 1-12 and chapter 139. Finally, he suggests that chapters 1-12 and chapter 13 were written by different authors (which would explain the differences between these texts), but the author of chapter 13 wrote this chapter later, and with the content of chapters 1-12 in mind (which would explain the points of contact between these texts). Since a difference of authorship implies different recipients and purposes, Wedderburn argues that chapters 1-12 and chapter 13 cannot be simply merged «into one harmonious whole»10. Although Wedderburn’s proposal is distinct from previous ideas in Hebrews scholarship11 that stipulated that chapter 13 was an appendix of the book or a later addition by another later writer to give the impression that Hebrews had a Pauline authorship, Wedderburn’s view of Hebrews is similar to these previous ideas in the sense that he emphasizes a discontinuity between chapters 1-12 and chapter 13.

However, Wedderburn is aware that his theory is not aligned with current trends in Hebrews scholarship, which does not regard the differences in style and vocabulary as evidence for discontinuity. In fact, he starts his article acknowledging that «it is generally thought that Heb 13 is an integral part of the document»12 and he will attempt to challenge this dominant trend. Indeed, Gert Steyn affirms that «most scholars these days are of the opinion that . . . Hebrews 13 is authentic and that it belongs to the rest of the book»13 and David DeSilva argues that «the literary unity of Hebrews is rarely challenged today»14. Overall, scholars have observed continuity between the last chapter and the other chapters of the book in terms of content and connections of style and form. From a thematic standpoint, DeSilva points out that «each exhortation» in chapter 13 «is directly relevant to the pastoral need addressed by chapters 1 through 12, giving the hearers specific directions concerning how they are to persevere in the face of a hostile society and arrive safely and unwearied at the goal of the “lasting” city that is to come»15. In his remarks on Heb 13:1-17, Luke T. Johnson argues that «virtually everything said here echoes earlier passages in which the author praises what his hearers are doing or exhorts them to do»16. In terms of style, Attridge highlights that the abrupt «shift in tone and style at 13:1 from the solemn warning of the previous pericope to the series of discrete and staccato admonitions that begin this chapter (13:1-6)» is «not totally unprecedented» in Hebrews. He mentions examples of similar abrupt shifts in 12:14 and 2517. With regard to the argument that the vocabulary of Heb 13 is different from Heb 1-12, Albert Vanhoye underlines that each section of 12:18-21 and 12:14-17 has fourteen words not found elsewhere in Hebrews18. This should minimize an overemphasis on the difference of vocabulary in Heb 13. From a formal perspective, based on Hellenistic rhetoric, Gareth Cockerill stipulates that Heb 13:1-17 is a peroratio, a final attempt of the orator «to move his audience in the desired direction», generally drawing «on the earlier parts of the speech, using short exhortations and vivid imagery»19. According to this perspective, the key point of continuity is 12:28-2920, a passage that concludes21 chapter 12 and provides the transition to chapter 1322.

In light of what has been discussed previously by the author of Hebrews, 12:28-29 basically exhorts the audience to have gratitude (ἔχωμεν χάριν) and offer worship/service acceptable to God (λατρεύωμεν εὐαρέστως τῷ θεῷ)23. Indeed, the exhortations to gratitude and worship/ service are related, as the latter is a relative clause subordinated to the former24. This syntactical relationship is properly captured by nasb25, «let us show gratitude, by which we may offer to God an acceptable service» (italics mine). As Attridge points out, «gratitude is part of the worshipful response that Hebrews tries to evoke»26. In this way, λατρεύωμεν «is the main thrust of the exhortation»27.

Before I move to the discussion on how the concepts of gratitude and worship in 12:28 inform chapter 13, it is important to recognize that vv. 28-29 add further details to these concepts. The exhortation to gratitude is justified positively by the idea that the audience of Hebrews is receiving an enduring kingdom (βασιλείαν ἁσάλευτον παραλαμβάνοντες, v. 28)28. In its turn, the encouragement to worship includes the suggested manner of performing this service, namely, «with reverence (εὐλαβείας29) and awe (δέους)» (v. 28). The ground for such manner of worship is the somber recognition that «God is a consuming fire»30. Thus, acceptable worship in 12:28-29 is related to the acknowledgment of the seriousness of divine judgment31.

However, how are the ideas of judgment and kingdom related? It seems that the answer starts in 12:22-23. According to these verses, the audience of Hebrews has «come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem», and «to God, the judge of all»32. If Zion is an allusion to the divine kingship33, the idea that believers have come to Mount Zion is consistent with the information in 12:28 that they are receiving a kingdom. In both cases, the divine kingdom is already a reality for believers, even though v. 28 implies that their complete reception of the kingdom still awaits a future fulfillment. Nevertheless, why is God called judge in this context, and not king? As a matter of fact, in many places in Hebrews God is portrayed as king in His throne (1:8; 4:16; 8:1; 12:2), having Christ seated at His right hand (1:3, 13; 8:1; 10:12; 12:2). Indeed, there are two important Psalms used by the author of Hebrews to develop the idea of Christ as co-regent king, namely, Pss 2:7 (see Heb 1:5; 5:5) and 110[109 lxx]:1 (see Heb 1:13; 10:13), 4 (see Heb 5:6; 7:17, 21). In Pss 2 and 110, Zion is mentioned (see 2:6 and 110[109 lxx]:2) as the place of the king. In Ps 2, the Son will destroy the nations (v. 9), as «his wrath is quickly kindled» (v. 12) against the rulers of the earth (v. 10), who are considered enemies of the Lord and his anointed Son (v. 2). It is noteworthy that, in this context, these rulers are advised to “serve (verb δουλεύω, lxx) the Lord with fear, and rejoice with trembling” (v. 11). Therefore, the enemies of the divine kingdom should serve Him with fear and trembling, having in view the destructive wrath of the king against them. In Ps 110 [lxx 109], read Christologically through the lenses of Hebrews, the Son (who is called Lord in the Psalm) sits at the Lord’s right hand as a co-regent king (v. 1, 5), and is also a priest according to the order of Melchizedek (v. 4). Similar to Ps 2, there is an emphasizes on the attitude of the divine king against His enemies (110:1-2), with special reference «on the day of his wrath» and his «judgment against the nations» (110:6).

Hence, if the ideas of kingdom and judgment in Hebrews 12:28 are thought from a Christological perspective of Pss 2 and 110, in Zion there is the divine kingdom and its judgment against the enemies. Furthermore, I suspect that a parallel can be drawn between Ps 2:11-12 and Heb 12:28-29. In this psalm, the enemies are advised to serve (verb δουλεύω, lxx) the Lord with fear and rejoice with trembling, having in view the destructive wrath of the divine king against them. In Heb 12:28-29, believers are exhorted to serve/worship (verb λατρεύω) God with reverence and awe, having in view His destructive judgment. Generally speaking, the content of the advice (Ps 2:11-12) and of the exhortation (Heb 12:28-29) is similar, but the concepts are nuanced differently by distinct words for service. Likewise δουλευω, λατρεύω means to serve, but it has a religious or cultic connotation, being used in Hebrews in terms of worship (see 9:9, 14; 10:2; 12:28; 13:10)34. Moreover, the advice is given to enemies, while the exhortation is addressed to believers. However, Heb 10:26 warns the Christian audience that «if we go on sinning deliberately» (Ἑκουσίως γὰρ ἁμαρτανόντων ἡμῶν), there is «a fearful expectation of judgment, and a fury of fire that will consume the adversaries» (italics mine). In this way, the fiery divine judgment will come against enemies or adversaries, and 10:26 seems to imply that, because of continual deliberate sin, those who were believers become enemies of God35.

The problem of sin is explicitly explored in Hebrews. As a matter of fact, it is because of Christ’s sacrifice and priesthood (see 9:11-14) that believers’ consciousness of sins is cleansed, enabling them to serve/worship (verb λατρεύω) God (9:14)36. In this sense, Christ’s priesthood is the basis for the worship believers offer to God. It is important to note that in the context where believers come to Mount Zion, while God is called the «judge of all», Christ is referred to as «the mediator of a new covenant» (12:22-24). In the other two instances where Christ is called mediator (μεσίτης) of a new or better covenant (see 8:6; 9:15), this mediation is related to His priesthood. Christ’s sacrificial death redeems people from their transgressions under the first covenant and enables them to receive the promised inheritance (9:15). If the reception of the kingdom in 12:28 is seen as the promised inheritance in 9:15, then Christ’s priesthood is not only the basis for the worship believers offer to God-as this priesthood purifies their conscience from sin, enabling them to serve/worship God, but Christ’s priesthood is also the basis for their reception of the kingdom under the conditions of the new covenant, because His priesthood redeemed believers from past transgressions and enabled them to receive the promised inheritance, the divine kingdom.

Concisely, because of Christ’s priesthood, believers are able to worship God and receive the kingdom, which are the themes of 12:28. Even the theme of divine judgment, mentioned in 12:29 as the reason for reverent worship in 12:28, can be seen in relationship with Christ’s priesthood. As indicated above, due to the continual practice of deliberate sin, a believer becomes enemy of God and will face judgment. What 10:26 adds to this picture is that «there no longer remains a sacrifice of sins» for that person. According to 10:29, the punishment of the former believer is deserved because he/she has «trampled under foot (verb καταπατέω) the Son of God» and «regarded as unclean the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified» (nasb)37. This statement has two basic implications: (1) the former believer has invalidated the priestly work that enables him/her, under the conditions of the new covenant, to receive the promised inheritance/the kingdom and to worship God in an acceptable way; and (2) comparing with 1:3 and 10:13, where Christ is waiting for his enemies be made a footstool for his feet, the former believer is treating Christ as enemy by trampling Him under foot. It is not a surprise that in the judgment he/she will be destroyed as an adversary. In this sense, by means of gratitude and reverent worship believers affirm Christ’s priesthood. On the other hand, the fiery divine judgment is the punishment for those who reject His priesthood.

How does this large picture of gratitude for the reception of the kingdom, which is a form of reverent worship offered to God in view of the divine judgment, and all these concepts connected with Christ’s mediatorial priesthood, inform chapter 13? Many scholars suggest that the exhortations to gratitude and worship in 12:28 take concrete form in the life of believers in chapter 1338. To put it in another way, gratitude and worship are the key concepts to start reading chapter 13. Koester even argues that the (medieval) chapter division of 12 and 13 «obscures the natural section break» in 12:28. For him, the last section (peroration) of Hebrews is 12:28-13:21, finished by a benediction (13:20-21), and followed by a conclusion in 13:22-2539. While there is no scholarly consensus on how to outline chapter 13, many scholars agree that 13:1-6 constitutes a subunit40. Therefore, for the purpose of this article, I will briefly describe the structure of this subunit for the discussion of marriage in 13:4, and assume that 12:28-29 is a key link between the subsection of 13:1-6 and the content elaborated until 12:27.

2. The Subunit 13:1-6. The Immediate Context Where Marriage is Mentioned

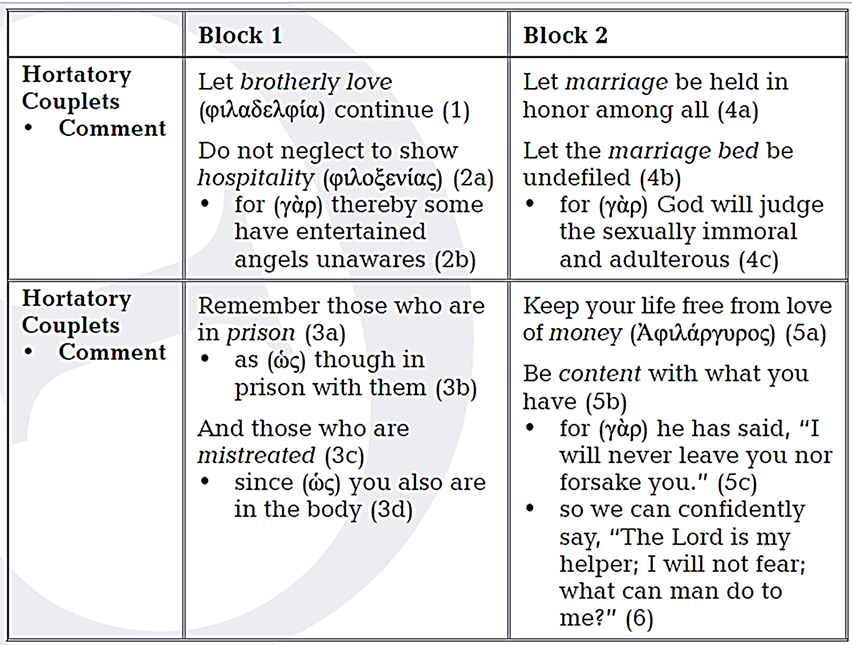

As Attridge points out, the subunit 13:1-6 is structured in «a series of four brief hortatory couplets asyndetically coordinated and interspersed with comments, which offer grounds for the exhortations»41. Emphasizing the link of this subunit with 12:28-29, Cockerill stipulates that these hortatory couplets indicate «how to live the faithful life of gratitude and godly fear within the community of God’s people»42. For a better visualization of these four pairs of exhortations, I will elaborate on Attridge’s suggestion that they are divided into two blocks, namely, vv. 1-3 and 4-643 (see Table 1).

From a linguistic standpoint, the main difference between the two blocks is that the first one uses imperatives for the exhortations, while the second block employs «predicate adjectives and a present participle [5b] with imperatival force»44. Conceptually speaking, it could be said that there is a communality between all the hortatory couplets, and at least two differences between the two blocks. On the whole, the four pairs of exhortations conceptually deal with love. The first couplet is related to brotherly love in general and brotherly love toward strangers, a love expressed by hospitality. The second pair deals with brotherly love toward those in prison and those who are mistreated, a love expressed by being empathically mindful of them, as if we were in their situation. The third couplet refers to matrimonial/sexual love. Finally, the fourth pair concerns the love of money. In terms of the conceptual differences between the two blocks, the first one stimulates the expression of (brotherly) love, while the second block is concerned with a distorted or perverted version of love. Therefore, whereas the first block highlights actions that need to be performed (show hospitality, remember those mistreated and those in prison), the second block emphasizes behaviors that must be avoided (adultery/sexual immorality, love for money)45 in order to maintain or protect an institution (marriage) and a Christian virtue (contentment46). The ideas of maintenance and protection are particularly evident in the language of holding marriage in honor (Τίμιος ὁ γάμος) and the undefiled marriage bed (ἡ κοίτη ἀμίαντος). In short, the first block stimulates the expression of love, with a focus on the brother or sister, whereas the second one warns against the distortion of love, with a focus on sexuality (adultery/immorality) and money (greed).

Another interesting difference is that God is mentioned in the second block. The fact that the attitudes toward marriage and money are somehow related to God should not be overstated. In 13:16, doing good and sharing (εὐποιΐας καὶ κοινωνίας) are actions classified as «sacrifices pleasing to God». In this sense, the practice of hospitality and the empathic concern for those mistreated and in prison could be regarded as sacrifices acceptable to God, inasmuch as they are interpreted as good works and altruism. On the other hand, the connection of block 2 with God does not derive from another passage in chapter 13, but appears already in the comments that «provide motivation for heeding the exhortations»47. More precisely, proper attitudes toward marriage and money are motivated by specific divine actions, judgment (expressed by the verb κρίνω) and provision/help (indicated by two statements from the ot48) respectively. The first action is negative, as it involves divine condemnation. The second one is positive, as it describes divine support.

Regarding the positive divine action of help, the author of Hebrews encourages believers to be confident (expressed by the participial form of the verb θαρρέω) about God’s action, which excludes the fear (expressed by the verb φοβέω) of human agencies (13:6). It is noteworthy that the verb φοβέω is used in another context to depict the faith (πίστις) of Moses’ parents and of Moses himself, as they did not fear the king’s edict (11:23) and his anger (11:27), respectively. In fact, 10:35-39 seems to indicate that the examples of faith provided in chapter 11 are mentioned to encourage confidence (παρρησία, 10:36) and endurance (υπομονη, 10:37)49. On the other hand, in the contrastive example of the Israelites that died in the wilderness (3:16-17), the lack of faith or unbelief (ἀπιστία) was the reason (see 3:12, 19) for them to receive the judgment of God in His wrath, not entering the promised land that is referred in Hebrews as the rest of God (3:11, 18; 4:3). Indeed, Num 14:9 clarifies the nature of this lack of faith/unbelief in the context of the narrative of this event. In the appeal made by Joshua and Caleb (see Num 14:6-9), it was evident that the Israelites were afraid of the people of Canaan (human agencies), instead of having the confidence in the divine provision, as expressed by Joshua and Caleb, “the Lord is with us; do not fear them.” Therefore, what seems to be clear in the theology of Hebrews is that, to use the language of 11:6, it is impossible to please (verb εὐαρεστέω) God without the confidence of faith50. This confidence is the basis for the contentment that avoids the love of money. According to this conceptual framework, such contentment pleases God, and considering that the adjective εύαρέστως and the verb εύαρεστέω are employed to describe the acceptable worship that believers are exhorted to offer to God (12:28) and the sacrifices of doing good and sharing that are pleasing to God (13:16), the contentment of believers in 13:5-6 could be conceptually seen as an attitude of worship to Him.

Up to this point, I have indicated how the couplets in block 1 are concrete forms of worship, as pleasing sacrifices of doing good and sharing, and how the second couplet in block 2 is a form of worship, as contentment expressed by a faith that pleases God. How about the first couplet of block 2, which refers to marriage? Can this couplet be understood also according to the concept of worship in Hebrews, as informed by 12:28-29? With this question in mind, I will move now to a more specific discussion of marriage in Hebrews.

3. Marriage in 13:4

Τίμιος ὁ γάμος ἐν πᾶσιν καί ἡ κοίτη ἀμίαντος, πόρνους γὰρ καὶ μοιχούς κρινεῖ ὁ θεός

As I have discussed above, marriage is mentioned in a hortatory couplet, which includes a comment that refers to God’s action of judgment to motivate, in a negative way, the audience to follow this exhortation (see Table 1). The hortatory couplet warns against the distortion of love. In this case, the protection of sexual love from perversion is achieved through a proper preservation of marriage. From a linguistic standpoint, the pair of exhortations about marriage do not use verbs, but predicate adjectives (Τίμιος, ἀμίαντος) with imperatival force51.

In the first exhortation, the adjective Τίμιος is placed in a position of emphasis (first position)52: Τίμιος ὁ γάμος ἐν πᾶσιν. This adjective conveys two related meanings, namely, being of exceptional value (costly, precious) and respected (held in honor, high regard)53. There are 13 occurrences of Τίμιος in the NT. Besides Heb 13:4, Τίμιος refers to a teacher held in honor (Acts 5:34), a precious life (Acts 20:24), Christ’s precious blood (1 Pet 1:19), precious promises (2 Pet 1:4), a precious fruit (James 5:7), costly wood (Rev 18:12), precious stones (1 Cor 3:12), and jewels (Rev 17:4; 18:12; 16; 21:11, 19). According to this perspective, in Heb 13:4, marriage (ὁ γάμος54) must be held in honor, which conveys the related idea of being regarded as something of exceptional value or precious. The prepositional phrase ἐν πᾶσ seems to imply that all people55, and not only the married couple, are involved in this practice of helding marriage in honor or attributing to it an exceptional value.

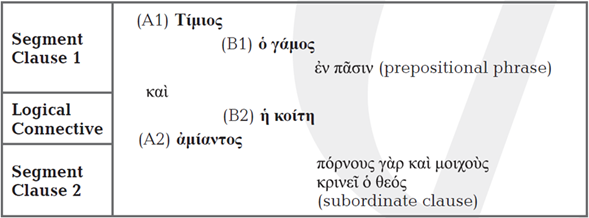

In contrast to the first exhortation, the next parallel exhortation has the articular noun in the first position of emphasis ἡ κοίτη. Such inversion seems to suggest a chiastic arrangement of this hortatory couplet56. If this suggestion is accepted, the content of v. 4 could be organized according to Table 2 57.

In this diagram, the parallel articular nouns ὁ γάμος and ἡ κοίτη constitute the central theme of the exhortation pair, and the parallel predicate adjectives58 Τίμιος and ἀμίαντος express what is expected about the central theme in the hortatory couplets. A comparison of the terms employed in segment clause 1 (Τίμιος, γάμος) and the ones used in segment clause 2 (κοίτη, ἀμίαντος) seems to indicate that the first exhortation is more general, while the second one is more specific59. The noun κοίτη conveys the related meanings of “a structure for laying down” (bed, marriage bed) and “engagement in sexual relations” (sexual intercourse, seminal emission)60. Considering the 4 nt occurrences of κοίτη, the term refers to bed (Luke 11:7), pregnancy (Rom 9:10)61, and sexual immorality (Rom 13:13)62. In Heb 13:4, the marriage bed or marital sexual relations (κοίτη)63 should be undefiled or pure (ἀμίαντος 64). In the 2 nt occurrences outside Hebrews, ἀμίαντος describes a pure and undefiled religion (James 1:27), and an imperishable and undefiled inheritance (1 Pet 1:4). In the other occurrence of ἀμίαντος in Hebrews besides 13:4, this term depicts Christ as a holy, innocent, and unstained high priest separated from sinners (7:26). Thus, ἀμίαντος tends to convey a moral, cultic, or religious sense of defilement. The language of defilement in Hebrews is also used in 12:15, which associates defilement with coming short of the grace of God. As a matter of fact, the warning about the danger of defilement precedes a reference to Esau’s sexual immorality in 12:16, an example that should not be followed by believers. This reference to Esau will be helpful for my comments on the justification or reason provided at the end of 13:4 for the purity of the marriage bed. Before I move to this justification, I would like to emphasize again that the hortatory couplet of 13:4 moves from a general to a more specific exhortation regarding marriage, with the implication that the «second exhortation makes the first more specific»65. In this sense, marriage bed/marital sexual relations (κοίτη) specify the topic of marriage (γάμος), and undefilement (ἀμίαντος) specifies the religious and moral sense of honor and value Τίμιος, in reference to marital sexual relations. In this way, the hortatory couplet could be understood as follows: marriage should be honored or regarded of exceptional value (exhortation 1), and «the most fundamental way of honoring marriage is by not violating the marriage bed through sexual relationships outside marriage»66 (the point of exhortation 2).

The more specific meaning of the second exhortation of the pair is confirmed by the reason provided at the end of 13:4 (πόρνους γὰρ καὶ μοιχοὺς κρινεῖ ὁ θεός to motivate the attitude advised in the hortatory couplet. Firstly, the nouns πόρνους (sexually immoral people) and μοιχοὺς (adulterers) is directly related to sexual relationships κοίτη which means that the explanatory reason67 at the end of 13:4 is more explicitly connected with the second exhortation of the pair. Furthermore, the prepositional phrase ἐν πᾶσιν at the end of the first exhortation suggests that this exhortation applies to the audience in general. Conversely, the inclusion of the subordinate clause that describes the motivation for the hortatory couplet, and more directly the second exhortation, has the effect of applying the second exhortation of the pair (and by extension the first exhortation) to a more specific group, namely, those who defile (in terms of sexual immorality or adultery) the marriage bed.

The specific group of people mentioned in the last part of 13:4, πόρνους (sexually immoral people or fornicators68) μοιχοὺς and (adulterers69), is basically characterized by sexual practices outside marriage. The nouns πόρνος and μοιχός are mentioned elsewhere in the nt in 1 Cor 6:9. Considering that these terms appear there separately in a list of unrighteous practices, they do not convey exactly the same meaning70. Since the related term πόρνη means prostitute71, the label πόρνους (fornicators) could refer to either married72 or unmarried people who practice sexual immorality, while μοιχοὺς (adultereres) would refer only to married people, as the concept of adultery implies unfaithfulness to a spouse73.

According to this perspective, the use πόρνους and μοιχοὺς in Heb 13:4 includes fornicators and adulterers, meaning that the defilement of the marriage bed would be caused not only by a married person having sexual relations outside his/her own marriage, but also by the sexual partner outside this marriage, who could be either a married (adulterer/fornicator) or unmarried (fornicator) person. Therefore, the general application (ἐν πᾶσιν) of the first exhortation in 13:4 (Τίμιος ὁ γάμος) is necessary, since the honor of a specific marriage depends on everyone, the husband and the wife, and also those who are outside this marriage, both married and unmarried people.

It is noteworthy that the first of the two occurrences of the noun πόρνος in Hebrews is found in 12:16, which refers to Esau as sexually immoral or totally wordly (πόρνος ἢ βέβηλος)74. While most translations render βέβηλος as godless (nasb, niv, nrsv, net), the more precise ide conveyed by this adjective is totally worldly («pert. to being worldly as opp. to having an interest in transcendent matters»75). While the OT never explicitly accuses Esau of sexual immorality, Cockerill stipulates that the key to understand this reference is the concept of bodily desire or pleasure76. According to this interpretation, the author of Hebrews «used the term “immoral” for Esau because he was controlled by bodily desire and because he “sold” the eternal for a pittance of the temporal»77 Indeed, Esau «wanted the pleasures of this world» and «he paid for that pleasure like one who hires a prostitute-one could say he sold himself for that pleasure. And what a little pleasure it was. (…) Esau sold his eternal “birthright” for nothing more than “one meal”»78.

Without entering into the discussion on whether this interpretation eliminates the possibility of a literal interpretation of Esau as πόρνος, in my estimation, Cockerill’s point does fit the argument of Heb 12:16. Esau’s sexual immorality and total worldliness is associated with the fact that he «sold his birthright for a single meal». As a result, «he was rejected», which means that he was unable to inherit (verb κληρονομέω) the blessing (12:17). Elsewhere in the NT, the language of inheritance (κληρονομέω) appears in statements where the noun πόρνοι (and also μοιχοὺς in 1 Cor 6:9-10) is mentioned, and the emphasis is that these people will not inherit (verb κληρονομέω the kingdom of God (1 Cor 6:9-10; Eph 5:5). In Rev 21:7-879, the language against against πόρνοις is strong. In contrast to the inheritance (the verb κληρονομέω is used) of the one who conquers, the πόρνοις will face the divine judgment depicted as «the lake that burns with fire (πυρὶ) and sulfur, which is the second death» (italics mine).

If these nt parallels are read together with Heb 12:28-29 and 13:4, the divine judgment (κρινεῖ ὁ θεός, 13:4) against those (πόρνους and μοιχοὺς) who defile the marriage bed (against exhortation 2), and dishonor marriage (against exhortation 1), can be related with the language of the kingdom and of the consuming fire of 12:28-29. The recipients of divine judgment in 13:4 will not receive the enduring kingdom mentioned in 12:28, but will face God as a consuming fire (12:29). Accordingly, their lives are not characterized by gratitude and acceptable worship to God (12:28). Conversely, the attitude of those who, being aware of the divine judgment, honor marriage and keep the marriage bed undefiled, could be seen as an act of gratitude for receiving the enduring kingdom and a reverent offering of acceptable worship to God.

Besides this conceptual connection between 13:4 and 12:28-29, a general parallel of the hortatory couplet of 13:4 (marriage) with the other pairs of exhortations in 13:1-2 (hospitality), 3 (empathy for those in prison and mistreated), and 5 (money) can be suggested. Reading these hortatory couplets with the historical situation of the immediate audience of Hebrews in mind, Koester argues that «those who show hospitality bring strangers into their homes (13:2)», and those strangers could be potential agents of marriage bed defilement in those homes. Moreover, «imprisonment of a spouse left the other spouse without marital companionship for an indefinite period (13:3)». Furthermore, «economic difficulties (13:5) sometimes led to the exchange of sexual favors in return for benefits»80. When the exhortation of 13:4 is read with these potential situations in mind, the honor and purity of marriage is elevated above any circumstantial need or temptation, as the rational offered for such honor and purity focuses on God’s action and not on human circumstances. In fact, the serious divine reaction (judgment) against those who dishonor and defile marriage gives an idea of the exceptional value (Τίμιος) that marriage has in the eyes of God.

Finally, it is noteworthy that the last Greek word in the hortatory couplet about prison/mistreatment, before the pair of exhortations about marriage in 13:4, is body (σώματι, 13:3). Indeed, body is a fitting term for the transition from the exhortation about mistreatment to the one about marriage. In 13:3, the body is explicitly the concrete object of mistreatment, but in 13:4 the body is implicitly the concrete agent of potential marital dishonor and defilement. The awareness that believers live bodily should lead them to an empathic concern for those being mistreated (the explicit point of 13:3), and it is also with their bodies that they honor or dishonor marriage. Accordingly, it is with their bodies that they show gratitude and offer reverent worship to God by honoring marriage and keeping it undefiled, just as it is with their bodies that they will face divine judgment if they dishonor and defile marriage (an implicit point of 13:4, when read in light of 12:28-29).

Conclusion

This article attempted to delineate the conception of marriage in the context of the theology of Hebrews. This attempt followed three steps: (1) it depicted the conceptual contours of the transition from chapter 12 to chapter 13, which highlights the theological tone of Hebrews; (2) it explored the conceptual micro-structure of 13:1-6 as the immediate context where marriage is mentioned; and (3) it delineated how the notion of marriage in 13:4 is connected with the two previous steps, showing how they inform the idea of marriage in that verse, especially in terms of an attitude of worship to God and the acknowledgment of the future divine judgment.

Overall, marriage in Hebrews is not an isolated concept merely mentioned along with other notions with no connections with the ideas developed in the epistle. Rather, a theological reading of 12:28- 13:6 provides a rich perspective for the understanding of marriage in Hebrews, as this reading uncovers connections and implications that are not immediately evident in a simple reading of 13:4.