Introduction

Some episodes, as the great depression that lasted until the 1930s, not only divided the world into defined areas, accentuating in this way the model of commercial self-sufficiency at an intraregional level, but it was also an essential trigger to one of the worst global conflagrations, that undoubtedly, ended up leaving its mark on the history of humanity. In this sense, the end of World War II may be regarded as a decisive episode for the resurgence of idealism in international relations. Therefore, the total absence in that period of the supranational and interstate structure influenced decisively to consolídate a system of international integration and cooperation nowadays (Cardona, 2018).

In fact, Mavroidis (2016) adds that Bretton Woods was not only to establish a series of rules to boost commercial relations among countries after World War II, but it also aimed at alleviating the marked protectionism of the interwar period that began in 1914 and ended in 1939. Then, this initiative promoted peace within the international political system, and it was necessary to adopt a series of economic opening strategies that foster foreign trade and the free trade of goods among countries. Likewise, it dealt with matters concerning international cooperation, public health, monetary and financial operations, and food security, among others.

Then, under the aegis of the United Nations, shaped in 1945, many global and regional institutions were created to face challenges that trans-cend national borders; all this, in a complex scenario where elements as economic globalization, state sovereignty, and the social policies about welfare states coexist. Therefore, these institutions and international rules have promoted the liberalization of cross-border flows of products and capital, thereby disseminating the free-market logic. However, there are still significant reluctances from several states that perceive, in this supranational system, commitments that may limit their ability to maneuver politically and economically; this is the reason why there is still many matters of political will to be resolved to move closer to the ideal of a world government (Fernández, 2009).

Likewise, in the economic domain, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was created in 1947, understood as a "code ofgood conduct". Based on the principle of non-discrimination, this legal framework stood out within the international rules that were successfully created along with the United Nations. Even though this agreement did not achieve all the objectives initially desired, it made significant progress for almost five decades through eight rounds of trade negotiations concerning tariffbarriers (TBS) and many other issues. It was after the last round of negotiations known as the Uruguay Round, that took place between 1986 and 1994, essential matters as non-tariffbarriers (NTBS), services, dispute settlement, agriculture, and matters relating to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) itself were finally covered (Kirshner, 1996; Jackson, 2000; Baena, 2018).

In this way, the setting up of the Multilateral Trading System or GATT- WTO paradigm was completed, which has developed specific rules homogeneous to all countries. Likewise, this paradigm shows several positive elements for the joint growth among those members who have participated in TBS and NTBS liberalization within their foreign trade. While there may be significant criticisms about its operation, it is still necessary to look for ways to revitalize the GATT-WTO system to favor more robust policies in the interest ofmost ofits members and the developing economies. In any case, it is clear that a multilateral system with difficulties is still a better option than each State going a different path according to its judgment that could undermine international trade stability and foreseeability (Lal Das, 2004).

Thus, Kinoshita and Barbosa (2016) add that the existence of GATT Article XXIV: "Territorial Application-Frontier Traffic-Customs Unions and Free Trade Areas" as well as the Enabling Clause ofthe 1979 Tokyo Round stand out within the rules developed in the current model ofthe Multilateral Trading System. The latter is due to these rules to provide a legal basis to the preferential exceptions, especially TBS, with no detrimental effect on the principle of trade without discrimination stipulated in the preface of the same agreement. Consequently, the then incipient Multilateral Trading System recognized an exception for those full members who signed trade agreements as a parallel alternative to liberalize trade worldwide. Even Herz and Wagner (2011) add that the multilateral liberalization of trade responds positively to the liberalization of regional trade in practice. In this way, international trade agreements can serve as essential elements to boost the process of cutting both TBS and NTBS in international trade.

Curiously, despite laudable intentions from Multilateral Trading System for reducing trade barriers legalizing international trade agreements, these last can mean a fragmentation of multilateral interest from the WTO. A situation that supposes different scenarios where a group of countries tries to solve trade issues together through reciprocal agreements or regional integration, giving rise to unnecessary fragmentation within the GATT-WTO paradigm. The preceding, because some agreements count with remarkable differences in terms ofpolitical and economic power besides geographical distance among their members, also exposing the complexity of the debate about what regionalism is (De Lombaerde, Sõderbaum, Van Langenhove, & Baert, 2010).

Bhagwati and Panagariya (1996) also pointed before regarding the inherent risks in the role of trade agreements because while these can help liberalize trade among the countries involved, they may also signify the creation of specific provisions or spurious rules. In this sense, all these rules may go against the fundamental interests of the current GATT-WTO paradigm and may even hinder trade flows given the challenges that traders may face due to having to comply with different commercial regulations that can result from these agreements and also from GATT.

Similarly, Wilson (2008) claims that the role oftrade agreements within the GATT-WTO paradigm may seem reasonable; this is because all of them impact on trade liberalization among countries besides they have existed since antiquity. Nevertheless, it is essential for this tool not to become an easy way out for states when the negotiations rounds within the WTO experience difficulties and avoid international trade agreements replacing the still under construction Multilateral Trading System.

In this sense, this paper offers through a descriptive study some sociological interpretations about how, on the one hand, Article xxiv was developed from GATT'S inception to legitimize the signing of bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, as is the case of free trade agreements (FTAS) and economic integrations (EIS) respectively. Likewise, on the other hand, some interpretations about how within the negotiation rounds of GATT, the Enabling Clause was necessary to legitimize the signing of trade agreements, especially unilateral nature, as preferential trade arrangements (PTAS).

Therefore, this article offers some reflections regarding the history of trade agreements, their generic nature, and the legal system for their legali-zation. Likewise, it is shown the behavior of international trade agreements exposing their nature and representation, the number ofinternational trade agreements notified before the WTO according to its legal framework, the international trade agreements in effect notified at the GATT-WTO paradigm to the present. Then, this scenario reveals a profound consensus crisis within the Multilateral Trading System and subsequently displays a transition from multilateralism to open regionalism.

International trade agreements and some reflections about regionalism and multilateralism

Agreements among politically organized regions date back to the period of Classic Antiquity. In this vein, within agreements, it has been usual to agree on specific issues that may be related to matters of peace, alliances, borders, among others, as was the case of the Ancient cities of Lagash and Umma in the region of Mesopotamia (Oduntan, 2015). In fact, one of the first agreements of which there is a historical record, trade-related in this case, dates from 1400 BC where the former Egyptian Empire and the Kingdom of Alashiya, now Cyprus, signed a treaty that granted island merchants exemptions in customs duties as a counterpart for the importing of a given amount of copper and wood (Bhagwati, 2008).

For this reason, many centuries later, it should not be surprising that what is thought to be the first FTA of the modern age. In this case, the renowned Cobden-Chevalier Treaty was signed in 1860 between France and England during a considerable and obscure period of trade protectionism. Therefore, this international trade agreement is considered a landmark in the history of international trade (Gowa & Hicks, 2018). Thus, the Cobden-Chevalier's relevance is related to booting the signing of new agreements in the region because nations were motivated to attempt the liberalization of their trade, which meant a falling average of 40 % to 8 % in customs tariffs according to different estimates (Millet, 2001). In addition, this treaty became a pioneer in implementing the Most-Favored Nation (MFN) clause, that established that the best deal negotiated with any other countries in other trade agreements should also be extended to them. Hence, this rule became an innovative element that, until the present, is considered an essential normative provision within the GATT signed in 1947 (Lampe, 2011; Corbin & Perry, 2018; Baena, 2020; Baena-Rojas & Herrero-Olarte, 2020).

In this sense, Orrego (1974) argues that GATT editors, aware of the exis-ting precedents in trade agreements and its dynamics within international relations, decide to incorporate the MFN clause, whose content is reflected in GATT Article I: "General Most-Favored Nation Treatment". Similarly, Article xxiv: "Territorial Application-Frontier Traffic-Customs Unions and Free-trade Areas" was also deliberately included as a possible exception to the MFN clause within GATT. Doing so enabled the setting up of commercial agreements from the beginning; on the one hand, of a bilateral nature or free trade agreements (FTAS) and, on the other hand, of a multilateral nature or also known economic integrations (EIS). The latter because the government contractors thought that if these liberalization mechanisms were not allowed, many countries would lose interest in becoming new GATT contractors (Lacarte & Granados, 2004; Kinoshita & Barbosa, 2016).

Nevertheless, according to Chase (2006) decades after GATT come into force emerged a vital loophole, in practical terms, into the treaty pointed in Article XXIV, that puzzled prominent theorist in this field because never was clarified if Article XXIV was an exception to the rule regarding the content of Article I.

Moreover, the main problem with trade agreements was specifically linked to unilateral trade preferences or preferential trade arrangements (PTAS). The above, because these treaties were not considered when GATT came into force because at first it was thought that an exception in this aspect could go against the very essence of GATT Article I. Then, some countries usuallyjustified granting special treatment considering the gaps in the applicable regulations, while these treaties just meant detriment of the MFN clause for many other countries (Condon, 2007).

In any case, all doubts about these international trade agreements were finally solved after creating the Enabling Clause in the 1979 Tokyo Round in the hearth GATT. In this manner, it was argued that this new normative provision could act as a clear, punctual exception to the MFN clause. All of this as long as the countries granting this type of PTAS, without reciprocity, did so under the premise of "differential and more favorable treatment" over developing countries; since otherwise, it would constitute a flagrant violation of GATT Article I (Jackson, 1997, Acua, 2003; Cardona, 2015).

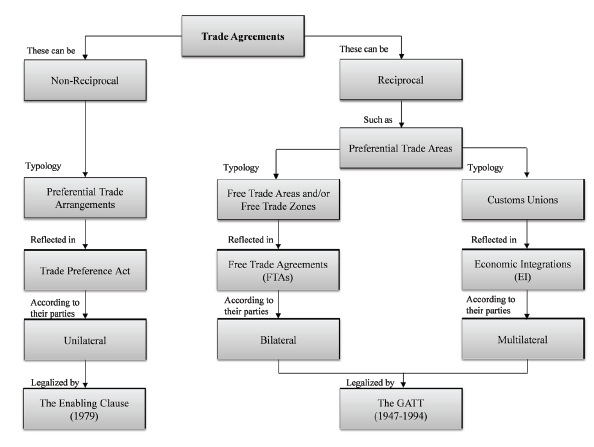

Consequently, the scenario for creating trade agreements of any type or nature (see figure 1) seems to have been wholly delimited at the normative level since then. In turn, other relevant commercial matters were also addressed in GATT'S rounds, remaining until the last one. The Uruguay Round (1986-1994), which after its closure, would bring the creation ofthe WTO one year after and reveal an increasingly favorable institutional and supranational environment for the liberalization of TBS and NTBS within the international trade.

It is necessary to indicate that all this matter related to supranationality within the GATT-WTO paradigm entails an intense debate because it is true that WTO as an international organization is not officially a supranational body with extraterritorial powers. Even their rules result from free negotiation between sovereign governments and within a consensus-based system (WTO, 1998). However, despite this official statement, the truth is that WTO possesses certain supranational dimensions, to the extent that litigation issues have been gradually deepened over time; i.e., WTO contains defacto limited supranationality, which is efficient over countries on certain occasions but not in all cases. In this way, the WTO still has limitations that prevent it from becoming a supranational entity, with all its virtues, maintaining the same essence as other international organizations with supranationality (Correa, 2005; Prado, 2010).

Thus, it may be said the current consolidation of the GATT-WTO paradigm began based on a fundamental international milestone as Bretton Woods in 1944 that led to the creation of multilateral institutions, that also influenced the strengthening of the international economic system as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (Jackson, 1997; Mavroidis, 2016).

In short, it can be asserted that international trade has been an economic process with many essential political and social transformations based on the state's decision-making. In this way, trade liberalization usually has been through international treaties among states with particular interests in specific geographic areas. However, World War I, the Great Depression, and the Second World War destroyed almost all the progress in trade liberalization that had been attained up, for years ago, to that point. In this manner, the idea that a peaceful world order could only rely on a stable international economic order gained strength led to institutional attempts supported on multilateral cooperation principles, Post-World War II, to liberalize and make better use of the world economy, giving rise to the GATT and subsequently to the WTO (Schütze, 2017; Goldstein & Van Lieshout, 2019).

Then, trade liberalization and trade openness can be understood as a result ofthe creation ofinternational trade agreements among geographically closer countries. This position is also known as open regionalism because countries looked for signing new treaties with their neighbors for joint growth among their parties. In other words, it was possible to change the economic model of many states regarding their foreign trade dominated for decades by the import substitution model where foreign trade ofstates changed their economic approach characterized mainly by the adoption of many different TBS and NTBS measures. Likewise, because ofthe openness via the GATT-WTO paradigm, this latter situation also gave to a different position known as multilateralism because countries could achieve joint growth grounded in the MFN clause, moreover, through rounds of negotiations to solve other trade issues. Hence, all this meant that states could go further in constructing a supranational model for developing standard regulatory provisions by consensus on a global scale (De la Reza, 2003). By all means, with the configuration of the GATT-WTO paradigm, multilateralism seemed to take on a significant role in international relations; considering this construct is based on critical aspects as universally applicable rules for all states within international law and on the collective form ofdecision-making where cooperation is essential (Manrique, 2009).

Consequently, states' foreign trade liberalization strategies based on treaties with other states seem to be subordinated to regionalism and multilateralism. In both cases, the dynamics and the approach to the integration of economies to cope with globalization are entirely different, but the goal tends to be the same where states seek joint development and growth (Grugel & Hout, 2005). Thus, the term of regionalism as a sociological phenomenon may be understood in two different forms. Firstly, traditional regionalism is characterized by adopting trade policies by a State focused on import substitution to promote economic development. In this sense, this type of regionalism implied less integration with the rest of the world, except for neighboring countries (Spindler, 2002). Secondly, open regionalism is characterized by implementing an economic integration strategy by a State to facilitate trade with neighboring countries and the rest of the world (Drysdale & Garnaut, 1993; Bergsten, 1997; Kelegama, 2000; Sõderbaum & Shaw, 2003).

In that way, it is necessary to highlight that the purpose in both classes of regionalism and multilateralism is to eliminate or reduce trade barriers, usually reflected in TBS and NTBS measures, according to the doctrine of economic neoliberalism (see figure 1). All of the above for promoting economic integration through the joint development within the economies of parties involved (Frankel, Stein, & Wei, 1997; Cancino, 2015; Herrero, 2017).

Source: Own elaboration based on Winters (1999), UNCTAD (2007) and Bouzas & Zelicovich (2014).

Figure 1 Regionalism and Multilateralism contextualization as socio-economic phenomena

Regarding the whole issue of differential and more favorable treatment to developing countries, previously stated, it is essential to clarify all this matter because it is merely obvious that traditional regionalism has been changing. Nowadays, in general, countries tend to use trade agreements to liberalize their trade reciprocally among different regions in the world. This situation implies leaving aside the role of preferential trade arrangements (non-Reciprocal) or PTAS, that aim to encourage the development of some countries with specific economic limitations. Thus, it is clear that new dynamics in international trade rises, since many countries end up imple-menting trade agreements, outside the GATT-WTO paradigm, in a context of economic asymmetries (Baldwin, 2012).

Furthermore, traditional regionalism has experienced a significant transformation as the states do not focus on negotiating new trade agreements on a specific region and with interests beyond the commercial, as it used to be decades ago. Instead, the current progression tends towards expanding a country's foreign trade regardless of geographic limits, without pursuing related objectives that could reduce asymmetries among economies; in other words, countries pursuit markets in an open regionalism model that reinforces commercial coalitions among states and even economic blocs. In this manner, given the current conditions of the GATT-WTO paradigm, multilateralism does not manage to solve the problems of asymmetries among countries, also apparently giving up ground to regionalism (Reyes, 2005; Bertoni, 2014).

Indeed, according to Guerra-Borges (2008), regionalism and multilateralism are instruments of globalization, and each one has a specific role in trade liberalization within the international economy. For that reason, both strategies seem to coexist and interact to seek solutions that ward off outdated commercial protectionism positions that may threaten global trade evolution through excessive TBS and NTBS adopted by some states.

In this regard, although the GATT-WTO paradigm has generated significant contributions in political, legal, and economic terms for ensuring long-term predictability to entire full members; the truth is that the current trade regime still seems to show relevant challenges not yet overcome to keep up with the trends as well as the dynamics of international trade. This situation is witnessed in the considerable number of existing trade agreements that do not undermine the WTO, for the absence of legal prevision within GATT and other legal texts, but rather the lack of management ability within the WTO to deal with a complex agenda saturated with difficulties (Barton, Goldstein, Josling, & Steinberg, 2006; Zelikovich, 2016). This has been observed in the controversial results of the Doha Round in 2001, the only negotiation round within the Multilateral Trading System framework up to this day, and the eleven WTO ministerial conferences (Ravi-Kanth, 2017; Baena, 2020; Baena & Londoño, 2020).

Consequently, there is no doubt as to the extent to which the WTO has been one of the most relevant bodies for the attainment of globalization and the development of trade policies that stimulate trade liberalization through the cutting of TBS and NTBS, bringing along significant effects for the economic growth of countries (Baena & Fernández, 2016; Baena, 2019). Nevertheless, the role of the supranational component seems in need to be reviewed, given that trade negotiations depend on the political will and the consensus of all WTO members. In addition, the fact that several sensitive issues in international trade as agriculture, services, market access for non-agricultural products, trade facilitation, rules, environment, intellectual property issues, dispute settlement, among others, have not yet been agreed upon and need to be regularly addressed, is to be taken into consideration. Additionally, there are still vestiges of the Great Recession amazingly, that took place a decade ago and still shows some traces of trade protectionism globally seeming to affect open regionalism, which has been stagnating to some extent (WTO, 2015; Cardona, 2017; Baena, Montoya, & Torres, 2017). This also includes the consequences of the recent world recession that originated during the pandemic in 2020 (World Bank, 2020; UNCTAD, 2020).

In other words, the GATT-WTO paradigm is living difficult times just like the Doha Round revealed and even just like the current reality still shows; all this due to the lack of consensus, which seems to have become a big blow for world trade governance. For this reason, it has been shaping yet again a more apt open regionalism for achieving precise goals within the states that seem to grant faster economic and commercial benefits rather than building more relevant and ambitious supranational initiatives worldwide (Wilkinson, 2017).

Methodological approach

First of all, to address the research problem raised within this article, it was essential to carry out a complete compilation of academic information, prioritizing databases of remarkable international recognition, as Scopus, Web ofScience (WOS), ScienceDirect, DOAJ, Scielo, and Google Scholar. In this way, keywords as regionalism, multilateral trading system, GATT, WTO, trade agreements, among others, were considered in both English and Spanish to increase the search possibilities within the works published in this field. Therefore, the literature review was carried out based on scientific highlighted papers; all ofthis, according to its number ofcitations, academic impact and current recognition.

Likewise, this research adopts a descriptive study that Lafuente & Marín (2008) defines as one where the features of a specific phenomenon are shown; all this, through the observation and measurement of its ele-ments. Thus, besides being an end in itself, the information provided by descriptive analysis can be used as a starting point for the development of a deeper and more detailed investigation. Similarly, the current work is based on a sociological reflection approach where it is also considered a factual question that allows addressing the central issue with rigor from the social science point of view (Giddens & Sutton, 2013).

In other words, is described the behavior of international trade agreements exposing their nature and representation, the number of international trade agreements notified before the WTO according to its legal framework, the international trade agreements in effect notified to the WTO according to their typology, and the international trade agréments in effect notified to the WTO from GATT and WTO creation to the present. In this sense, the sociological research scientific approach is applied where a factual question is proposed, see table 1 and figure 2, to analyze the central subject of this study.

Table 1 A sociological approach based on a factual question

Source: Own elaboration based on Giddens & Sutton (2013).

*According to the wto (2020), all the international trade agreements must be reported to this organism under international treaty law and established depositary practice to validate these kinds of treaties.

Source: Own elaboration based on Giddens & Sutton (2013).

Figure 2 Phases for the current process of research

As a central hypothesis of this study, it is proposed that legitimization of the international trade agreements and creation of the WTO originated a surprising emergence of various international trade agreements. Then, this scenario has generated remarkable trade liberalization between its signatory countries and generated, contradictorily, new legal systems outside the WTO.

In this way, this proliferation of international trade agreements discloses the functional problems and difficulties of consensus among full members to conclude the negotiation rounds within the GATT-WTO paradigm. These rounds increasingly ambitious due to the multiplicity of accumulated issues that tend to remain unfinished. A situation that reveals, in short, how within the international trade seems to parado-xically prevail a strategy of foreign trade policy, among the states, of regionalism and not of multilateralism as the WTO itself has advocated since its creation.

Subsequently, for the elaboration of the results of the present investigation, official statistics of the World Trade Organization (wto) were also considered, where databases as “Regional Trade Agreements database” and “Preferential Trade Arrangements database” can be accessed explicitly in whose content the current inventory of trade agreements is related within the Multilateral Trading System. In this manner, with all this information, it was possible through different tables and figures to carry out a descriptive study on the current behavior of international trade agreements within the GATT-WTO paradigm.

Conducting research and results

After looking into the above sections on the historical emergence of trade agreements within the GATT-WTO paradigm, it is necessary to identify the generic nature of said agreements (see figure 3), bearing in mind that these can vary depending on their reciprocity level. In this way, these types of treaties are identified and categorized from the literature published so far. Then, their typologies are defined considering if these are reciprocal agreements or not, in which commercial treaty they are reflected, how they are usually known according to their parties, and finally, under which GATT normative provision or legal text they are legitimized.

Source: Own elaboration based on Kolb (2008), WTO (2019a) and Amadeo, & Estevez (2021).

Figure 3 Nature and sociological representation of the Trade Agreements as an open regionalism instrument

Overall, it is possible to state that international trade agreements can therefore be non-reciprocal or reciprocal. In the first case, only one party grants tariff preferences and liberalizes its trade in specific sectors without expecting the counterpart to do the same. In the second case, all parties give each other tariff preferences, and all liberalize their trade directly. In this sense, reciprocal agreements can be understood in their turn as preferential trade areas and are presented below two typologies known as free trade areas and customs unions, whereas in the case of non-reciprocal agreements, there is only the typology of preferential trade arrangements.

These last are often unilateral and legalized by the Enabling Clause. While free trade agreements and economic integrations are often bilateral and multilateral, both legalized by GATT Article xxiv (OECD, 2007; Baber, 2019).

After showing the nature ofthe international trade agreements, it is also necessary to provide some relevant statistical figures about them, clarifying that the present information is based on the notification carried out by the countries before the WTO for the case ofmerchandises. In this way, there may be variations in the actual number of existing agreements so far; besides, in this number, new member accessions to a single agreement are usually included as well as enlargements to existing treaties. Thus, according to the records of the agreements currently in effect (see figure 4), it can be stated that there are currently 343 agreements reported on the WTO. With these, the countries seek to liberalize their trade, validated for the GATT-WTO paradigm effectively; all this from the logic of open regionalism where there can even be a harmonization of the member countries' commercial regimens in cases when the multilateral system's norms do not succeed in regulating punctual matters (De la Reza, 2013).

Source: Own elaboration based on WTO (2019b) and WTO (2019c).

Figure 4 International trade agreements notified before the WTO according to the GATT provisions and other legal texts

International trade agreements, in general, are legalized through GATT Article XXIV and the Enabling Clause when they are notified to the WTO (De la Reza, 2015). In this manner, of the 34 existing preferential trade arrangements, 100 % are legalized through the Enabling Clause, while from the 291 preferential trading areas, 248, equivalent to 85,22 %, have been legalized through GATT article xxiv, and the remaining 43, equivalent to 14,78 %, through the Enabling Clause. Additionally, ifnew member accessions and time extensions are added to these agreements, it can be observed that 13 from a total of 18 accessions or extensions, equivalent to 72,22 %, have been legalized through GATT article xxiv, whereas the remaining 5, equivalent to 27,78 %, have been legalized via the Enabling Clause.

Subsequently, regarding the typologies ofthe existing trade agreements within international trade, without considering accessions or enlargements, a total of 325 agreements can be identified today (see figure 5). These are not used only to liberalize trade between the parties; given the relative easiness with which countries carry them out, they tend to imply fundamental challenges from the global economic governance for the GATT-WTO from the supranationality perspective (Nakagawa, 2012).

Source: Own elaboration based on WTO (2019b) and WTO (2019c).

Figure 5 International trade agreements notified to the WTO by typology

Mostly international trade agreements correspond specifically to free trade areas or free trade zones, that report 249, equivalent to 76,62 % of the total agreements. In the second place, there are 34 preferential trade arrangements equivalent to 10,46 %, followed by 22 partial scope agreements equivalent to 6,77 % (these are understood as a previous stage to the economic opening process, in which case tariff preferences are generated only for specific merchandise). Likewise, there are 20 customs unions equivalent to 6,15 % of international trade agreements in force nowadays. Regarding free trade areas or free trade zones stand out from the rest of typologies since, on the one hand, these trade agreements are usually easy to carry out as compared to customs unions due to the role of supranationality, interdependence, and other issues beyond the commercial that are involved in these later (Perdikis, 2006; Hamanaka, 2012). On the other hand, many preferential trade arrangements have ended up becoming free trade areas or free trade zones when the granting country decides not to renew them to the beneficiary countries (Lavopa, 2012; Lavopa & Dalle, 2012; Baena, 2020; Baena-Rojas, & Herrero-Olarte, (2020).

Finally, regarding the behavior over time ofinternational trade agreements since the GATT creation so far, it is possible to highlight that although the states have been able to carry out trade agreements since many years ago, this has been done under inevitable debate. Within the GATT-WTO paradigm, free trade areas and customs unions have been carried out in legal terms since the GATT and its article XXIV came into effect as of 1947. Likewise, in the case of preferential trade arrangements, said legality was possible until the Tokyo Round, when the Enabling Clause was developed in 1979 (Das, 2004). In this vein, it is possible to state that the effective configuration of the GATT-WTO paradigm after the Uruguay Round in 1995 (see figure 6) flourished the creation and signing ofvarious international trade agreements to liberalize trade while giving a central role to open regionalism.

Source: Own elaboration based on WTO (2019b) and WTO (2019c).

Figure 6 International trade agreements signed in the GATT'S regime and notified to the WTO

The evidence suggests that international trade agreements were not historically significant in the first or the second decade of the GATT regime, given that until the decade of 1960s, two agreements had been reported, and two further agreements until 1970 for a total of four trade agreements. This figure did not change until 1980 when 16 new agreements were recorded, and later in 1990, another ten were recorded, reaching an accumulated total of 30 agreements. The creation of the Enabling Clause can explain this scenario in 1979 and the new trends, in which case the import substitution model lost force within international trade (Cardona, 2018).

Afterward, until 2000, 40 new trade agreements were recorded, for an accumulated total of 70 treaties, which meant that more agreements were created in one decade than those produced during 40 years ago, a situation also explained by the creation ofthe WTO and with this the consolidation of the GATT-WTO paradigm (Acharya, 2016). Later, the most relevant number of new agreements was recorded until 2010, reaching 142 for an accumulated total of212 treaties. Lastly, from 2011 to 2019, 113 new agreements have been recorded for an accumulated total of 325 trade agreements, which seems to evidence that in this last decade, the Great Recession effects have led to interference in the process of trade liberalization (Baena, Montoya, & Torres, 2017) trough open regionalism in this case.

Conclusions

Since the setting up ofthe GATT-WTO paradigm, as a sociological pheno-menon within International Relations, free trade areas and customs unions were completely validated through GATT Article xxiv. Likewise, preferential trade arrangements were validated through the Enabling Clause of the Tokyo Round. Therefore, there is no doubt regarding the legality of this type of liberalization mechanism within international trade.

Nowadays, a total of325 trade agreements are quantified, among which free trade areas or free trade zones stand out. These make up more than two-thirds of the total existing agreements so far, with 249 agreements. Since these are usually bilateral, it can facilitate its negotiation process compared to other agreements as the multilateral where the consensus can represent greater challenges.

Likewise, about partial scope agreements, which account for 22 of the totals, it is essential to indicate that these usually end up becoming free trade areas or free trade zones. In the case of preferential trade arrangements, which account for 34 of the total, these seem to lose their central role since a good number of them have ended up expiring, without unilateral tariff preference extensions from granting countries; thus, many ofthese treaties ends in free trade agreements. Regarding customs unions, which account for 20 of the total agreements, their role is minimal in terms of the number oftreaties precisely due to the consensus challenges previously mentioned, besides the multiplicity of issues beyond the commercial involved in this type of international trade agreements.

Also, the evidence showed that the proliferation of trade agreements has soared since the creation of the WTO, changing the approach from traditional regionalism to open regionalism, a situation that seems to undermine multilateralism. The latter, perhaps because the liberalization of trade should be from idealism view in International Relations through the GATT-WTO paradigm and not from a specific group of states by their own, which even creating rules outside the GATT provisions and legal texts for regulating everything that is not possible in the Rounds of the WTO.

Then, the underlying issue has to do with the sociological challenges and unachieved issues of the GATT-WTO paradigm related to its capacity. This situation reveals the failure in consensus among the full members, preventing to move closer to the ideal model of world government. In this manner, the effort can be directed to managing the commercial outcome of the globalization process, which is gaining more and more weight on the national stage in each state. Therefore, the direction of the WTO'S discourse is necessarily solved the political will matter, beyond original purposes associated with multilateralism.

Finally, as future lines, it is essential to conduct these descriptive studies based on a sociological reflection approach to analyze social phenomena in International Relations and ensure the conceptual rigor based on the facts.