Introduction

Marine microorganisms are a novel source of biologically active compounds which can influence the growth of pathogens [1]. Recently, metabolic profiles of selected strains of marine bacteria from the Colombian Caribbean Sea have been conducted in order to identify bacteria extracts with antibacterial effect, quorum quenching, and antifungal activity [2], with the aim of using them as phytopathogic biocontrol agents.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) from bacteria have been studied as responsible of fungal-bacteria interactions [3, 4] acting as infochemicals in interactions among microorganisms [5] and promoting plant growth [6]. Fungi and bacteria can establish volatile mediated molecular communication that can be used to modulate the antagonistic answer of bacteria against the negative effect of fungi of a pathogenic nature, avoiding spore germination, and thus reducing growth, even decreasing pathogenicity [3, 7].

VOCs have great relevance for their applications as controllers, which takes advantage of the inter- and intra-specific communication between microorganisms through secondary metabolites, thus making it a promising environmentally friendly crop protection strategy. As a result, the use of VOCs could be a possible substitute for hazardous chemical pesticides and fertilizer.

Hundreds of VOCs released from bacteria have been identified [8, 9]. Such VOCs profile can vary depending on several factors, such as the culture media, microorganism growth stage, temperature, and even the used volatile extraction methodology [3]. Indeed, it is necessary to identity them in the specific conditions and their biological activity to get a well-defined combination of several VOCs, that could influence behaviour in fungi with accuracy.

According to current knowledge, VOCs are generally produced by catabolic pathways and belong to different chemical classes of organic compounds [8]. Acetamide, trimethylamine, 3-methylamine, 3-methyl-2-pentanone, benzaldehyde, N,N-dmiethyloctylamine, benzothiazole, phenylacetaldehyde, cyclohexanol, nonanal, dimethyl trisulfide among others have been identified and described as VOCs released by several strains with activity against other organism such as fungi [9].

In the present work, our goal is to identify some VOCs, released by marine bacteria which are able to control the yam phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B. In particular, we use eight bacterial isolates obtained from marine environments, collected at coral reefs of Providencia and Santa Catalina (Colombia). To identify the antifungal activity of released VOCs against the pathogenic fungi Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B, we use a petri dishes methodology avoiding direct bacteria-fungi contact to determine mycelia growth inhibition (%) and we also evaluated the stimulation of spore germination. To evaluate only the VOCs' activity, a headspace test was designed, and HS-SPME and GCMS was used for VOCs extraction and putative identification.

Materials and methods

Yam Phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B

The phytopathogenic fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B, obtained from yam plants with classical symptoms of anthracnose, was provided by "Grupo de Estudio en Ñame" from the Biotechnology Institute of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia (IBUN). The phytopathogen fungus was reactivated (by inoculating the yam tuber), fungus was grown in potato dextrose agar (PDA), and once its maximum growth was reached in a 90 x 15 mm Petri dish (at 25 °C for four days), the spores were scraped. Those spores were suspended using 25 mL of the solution of 0.85% NaCl + 0.1% sterile Tween® 80, then it was filtered and collected in 50 mL falcon tube. Using 10µL of the solution, the count of conidia was performed using the Neubauer chamber (2.9 x 106 conidia/mL). Besides, 10 µL of this solution was inoculated on the sterile yam slides. After 3 days of growth, conidia of the pathogen that grew on the yam were taken and inoculated in PDA. For long-term storage, small portions of an actively growing colony were brought into fungi preservation medium stored at -80 °C (Luria-Bertani LB solution fortified with glycerol 80%). A second suspension for short-term maintenance was stored at -20 °C (Luria-Bertani LB solution fortified with glycerol 20%).

For the inoculation of the pathogen, 100 µL of suspension stored at -20 °C was grown onto PDA, then the pathogen was gently scraped off the surface by hand with 5-10 mL of 0.85% NaCl + 0.1% sterile Tween® 80 solution to detach conidia. Finally, the resulting spore suspension was passed through sterile cotton to remove the mycelial fragments, obtaining a conidia solution of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B.

Marine bacteria

Eight bacterial isolates (Table 1) were selected from a collection obtained from the coral reef of Old Providence and Santa Catalina islands (Colombian Caribbean Sea). For this study, we selected Paenibacillus strains because this genus was proposed as potentially effective biocontrol and plant growth promoting agent in previous research [10-12].

Table 1 Selected bacteria for antifungal activity screening.

| Code | Taxonomic identification of each straina (% Similarity) | Source | Morphology | Gram |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNM24 | Paenibacillus elgii NBRC 100335 (99.9%) | Mangrove bark | rod-shaped | Positive |

| PNM32 | Paeiiibacillus ehimensis IB-739 (99.8%) | Coral sand-pinnacle | rod-shaped | Variable |

| PNM34 | Paenibaciilus ehimensis HSCC-594 (100%) | Niphates digitalis | rod-shaped | Positive |

| PNM50 | Paenibacillus ehimemis NBRC15659 (100%) | Codium (algae) sp. | coccobacillus | Variable |

| PNM54 | Paenibacillus ehimemis NBRC15657 (99.9%) | Codium (algae) sp. | rod-shaped | Variable |

| PNM63 | Paenibacillus ehimensis NPUST1 (99.9%) | Unknow | coccobacillus | Positive |

| PNM65 | Paenibacillus ehimensis NBRC15659 (100%) | Niphates digitalis | rod-shaped | Positive |

| PNM68 | Paenibacillus ehimensis NBRC15657 (99.9%) | Niphates digitalis | rod-shaped | Positive |

a Determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing in previous studies in our research group (unpublished data).

All the strains were registered in the collection of microorganisms of the IBUN and were preserved in cryovials at -80 °C, each vial containing 1 mL of the suspension resulting from scraping with 10 mL of solution of Luturia Bertani broth modified with glycerol 85%.

Screening of VOCs antifungal activity

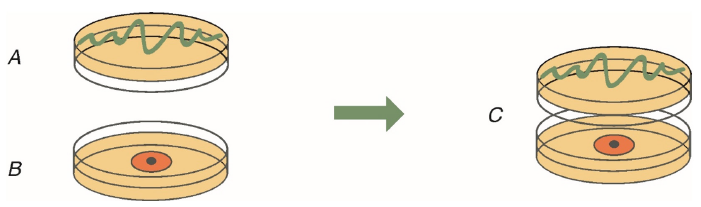

To evaluate the antifungal activity of VOCs released by the eight marine bacteria, both organisms (respective bacteria + fungi) were grown in separate petri dishes, then they were put together avoiding direct contact between both microorganisms (Figure 1), as follows: Bacterial strains were grown in Muller Hilton (MH) Agar plate by striatum in a Petri box (90 x 15 mm). Over a second Petri dish, the pathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B was inoculated in PDA, using 10 µL of a solution of conidia (2.9 x 106 conidia/mL). The box containing the bacteria was placed on top and inverted over the one that kept the pathogen fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B (Figure 1). The boxes were sealed with Parafilm™ tape to prevent the escape of VOCs and incubated at 28 °C for 10 days, because according to our experimental results, this is the necessary time for the fungus to reach its maximum growth in a 90 x 15 mm Petri dish. Growth inhibition of pathogen caused by bacterial VOCs were measured at the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day of inoculation. Plates with C. gloeosporioides cultured on PDA in the absence of the bacterial strain were used as negative control. Each assay was performed by triplicate with three independent cultures for each strain.

Figure 1 Experimental design to test the antifungal activity of bacterial VOCs. A). Bacterial strain growth in Muller Hilton (MH). B). Phytopathogen C. gloeosporioides 26B growth on PDA medium. C). Both Petri dishes were sealed with ParafilmTM tape facing each other to obtain a double-plate chamber.

The diameter of each fungal colony was measured on the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day after inoculation. The fungus size is measurable after three days of growth and on the tenth day it covers the entire of Petri dish area. Three measurements of length per box were made each day using photography. The ImageJ 1.x Java [13] public image processing program was used to carry out the measurement. The inhibition percentage against the phytopathogenic fungus was calculated using Eq. (1).

Here, td is the diameter of the fungal colony in the presence of the bacterial isolate and cd is the diameter of the fungal colony of negative control.

The Paenibacillus isolates, with inhibitory activity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B higher than 50%, were also tested on Nutritive Agar (NA) (yeast extract 3 g/L, beef extract 3 g/L, peptone 5 g/L, and NaCl 5 g/L), International Streptomyces Project (ISP2) (yeast extract 4 g/L, malt extract 10 g/L, and dextrose 4 g/L); Mueller Hinton (MH) (beef extract 2 g/L, hydrolizated casein 17,5 g/L, and starch 1,5 g/L) and Luria Bertani (LB) (yeast extract 5 g/L, NaCl 10 g/L, and tryptone 10 g/L) media following the same procedure.

In addition, the effect of the VOCs on the conidia number was measured on the 10th day, following the methodology of Perez et al. [14]. In brief, 5 mL of solution, 0.85% NaCl, and 0.1% Tween® 80, were added over a fungus culture previously exposed to VOCs in order to obtain the conidia suspension. Using a Neubauer chamber the number of conidia (10 µL of suspension) were counted. The same procedure was carried out without exposure to volatiles from bacterial isolates, serving as negative control.

Identification of VOCs by HS-SPME-GC-MS

In 100 mL glass vials, containing 20 mL of culture medium, 100 µL of each strain was inoculated in LB culture media, with an optical density OD600 of 0. 456 ± 0.005 (Elisa absorbance reader, IFS).

The systems were sealed with air-tight Teflon septum and an aluminium cap and were kept in incubation at 28 °C for 10 days.

VOCs were collected on a divinylbenzene/carboxen/ polydimethylsiloxane fiber (DVB/CAR/PDMS, 50/30 um, Supelco®, Bellefonte, PA, USA) for 15 min on the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day of inoculation, i. e. at the same points of time as the inhibition measurement described above. SPME fiber, HS volume, and time conditions were selected according to previous studies (data not shown here).

SPME samples were analysed using a GC-MS-QP2010S from Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) and a capillary column SLB®-5ms-28471-U (Sigma-Aldrich) (30 m x 0.25 mm, df 0.25 µm). Helium was used as carrier gas with a flow rate of 1.20 mL/min. Manual injection for 5 min was done in splitless mode (1 min), the injection port and transfer line temperature were set at 250 °C. The column oven was programmed from 50 °C; increasing to 190 °C at 6 °C/min, then 12 °C/min to 230 °C and held at that temperature for 5 min. Mass spectrometry analyses were done in full-scan mode using an electron energy of 70 eV and the m/z range was 35-350 with a scanning speed of 0.50 scans/s.

VOCs were putatively identified by comparison of their retention indeces (RI) calculated by using the headspace of a mixture of alkanes (C6-C26) with those informed by the literature or standards. The signals from control culture media must be subtracted of each TIC to be analysed. The obtained mass spectra were compared to those present in the libraries NIST/EPA/NIH (National Institute of Standards and Technology) and VOC databases available online (http://bioinformatics.charite.de/mvoc) [15].

Results and discussion

Yam (Dioscorea sp.) is an important crop in tropical and subtropical regions around the globe [16]. In Colombia there are 340,000 hectares of it, with a production of 85,000 tons per year. This crop is affected by different fungi, including Fusarium oxysporum, which has been associated with dry rot in yam tubers, and the fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, which causes Yam anthracnoses [16]. In this context, we are looking for bacteria that are capable of controlling C. gloeosporioides and we focus on Paenibacillus species due to their potential in the development of biocontrollers.

Bacteria of the genus Paenibacillus comprise bacterial species that have been reported as symbionts of plants such as corn, squash and rice, and it has been identified that they can promote their growth [17, 18]. They are widely distributed around the globe. In fact, they have been isolated from soils, plant roots, polar regions, marine environments, and even deserts. This genus of bacteria has been characterized as producer of enzymes such as amylases, cellulases, hemicellulases, lipases, pectinases, oxygenases, dehydrogenases among others, which may have applications for detergents, foods, textiles, etc [17]. Antimicrobial compounds have been isolated from bacteria of these genera. In this context, we selected eight marine bacteria of genus Paenibacillus to evaluate their capability to release VOCs with antifungal activity.

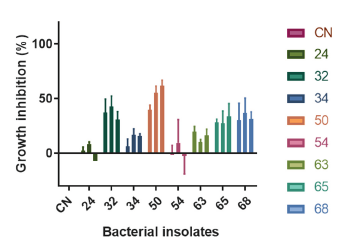

To assess the effects of VOCs released by each bacterium on the growth of yam fungi pathogen Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B, both microorganisms were cultured at the same space avoiding their direct contact, as is shown in Figure 1. VOCs produced by four marine bacteria denoted as PNM-32, 50, 65, and 68, inhibited the mycelia growth of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B as significantly different from the control (P < 0.05). Figure 2 shows the % inhibition presented by each bacterial isolate. Overall, growth inhibition rates over pathogenic fungi increase with incubation time.

Figure 2 Antifungal activity screening. The radial mycelium growth of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B was determined on the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day of inoculation and the percent inhibition compared to the control growth was calculated. All strains were evaluated in three independent replicates. Error bars indicate ± SD.

Since the VOCs released by PNM 50 show the highest mycelia inhibition rate (61.5 ± 5.3% after 10th day of inoculation), PNM 50 was selected for chemical study. PNM 50 was identified as Paenibacillus ehimensis NBRC15659 (100%) by 16S rRNA gene sequencing (unpublished data).

The impact of culture media on bacterial metabolic profiles is well known [19]. To establish the effect of culture media on VOCs composition (qualitative and quantitatively) and their antifungal activity, we studied the impact of four different culture media (MH, NA, ISP2, and LB) on mycelia growth inhibition (Table 2).

Table 2 Antagonistic effect of volatile organic compounds from Paenibacillus PNM50 against C. gloeosporioides 26B on four media on the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day of co-cultivation.

| Media | Growth inhibition (%) | % Conidial reduction 10th day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd day | 6th day | 10th day | ||

| (NA) | 29.6 ±6.5 | 31.5 ±7.4 | 27 ± 12 | 92.1 |

| (MH) | 36± 12 | 27± 18 | 37.8 ±9.1 | 94.4 |

| (ISP2) | 41.8±4.6 | 35.0 ±5.0 | 28.3 ±9.8 | 95.2 |

| (LB) | 40.8 ± 3.0 | 39.3 ±4.5 | 40.8 ± 3.4 | 96.5 |

n = 3, ± SD.

In all used media mycelia growth inhibition of phytopathogenic fungi by VOCs was observed (Table 2), as well as morphological changes on C. gloeosporioides 26B, such as changes in mycelium colour. The highest inhibition percentage was obtained when PNM-50 was grown over ISP-2 and LB on the 3rd day of incubation.

There was a greater inhibition of the phytopathogen when the culture medium (LB) is rich in yeast hydrolysate, which suggests that the presence of this component would contribute with the content of vitamins, amino acids, and growth factors, thus favouring the production of VOCs in bacterial isolates. Finally, the LB medium was selected for VOCs analysis.

Our results allow to point out that a culture medium serves in the first instance as external nutrient source to promote bacterial growth. As a result, greater biomass is generated, and therefore, a greater amount of active metabolite is synthesized. Secondly, some of the medium compounds could be involved in the production of active metabolite, specifically in this study yeast hydrolysate could play that role. Furthermore, there is a complex effect by interacting the culture medium- bacterial- fungal volatile emissions, as reported an ongoing dialog between the pathogen Verticillium longisporum and its antagonist Paenibacillus polymyxa [12].

In addition, the production of fungi conidia in four tested media was measured on the 10th day obtaining a conidial reduction of 92-97% in all media. This result would be associated with the reduction in the size of phytopathogen fungal colony in all the examined cases, indicating that at a lower mycelial mass, there is a lower number of asexual spores. The conidiation reduction further suggests that the exposure to VOCs emitted by bacteria influences the reproductive processes of phytopathogen and, therefore, the probability of infection would be reduced.

The next step was to identify the compounds released by PNM-50. HS-SPME and GC-MS were used for extraction and analysis of VOCs from the bacterial isolate Paenibacillus PNM-50 grown on LB media. The VOCs were analysed on the 3rd, 6th, and 10th day (Table 3).

Table 3 Identified Volatile Organic Compounds from Paenibacillus PNM50 grown on LB media

| Putative identified Compounds | Experimental | Area % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rt (min) | RIDB-5 | m/z base peak | 3rd day | 6th day | 10th day | |

| 2-fiiranmethanol | 11.581 | 1110 | 39 | 20 | nd | nd |

| Phenylacetonitrile | 12.278 | 1138 | 117 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| undecanoic acid | 20.842 | 1497 | 60 | 1 | nd | nd |

| 2,4-dimethyl pentanol | 22.977 | 1597 | 44 | 4 | nd | nd |

Rt= retention time. RI= retention index for the bacterial headspace volatiles were calculated using the headspace of a mixture of alkanes (C6-C26). Area % = relative peak area of the total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the peak corresponds to the abundance of each compound after subtraction of COVs from culture media. nd= non-detected. Identification was done by retention index comparison with those from literature and mass spectra comparison with those from NIST data base.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of VOCs produced by the culture media. For the identification of VOCs produced by bacterial isolates, the signal of compounds observed from the control culture media must be subtracted from the signal from the bacterial cultures in order to avoid misidentification of bacteria-produced compounds. In this way, PNM-50 exhibits only four compounds as true bacterial VOCs: 2-furanmethanol, phenylacetonitrile, undecanoic acid, and 2,4-dimethylpentanol. We also identified the compounds coming from the culture media. Amongst these, benzotiazol, was reported in previous studies [4, 20-22] as constituent of the VOCs produced by bacteria. Furthermore, it has been tested for its antifungal activity showing mycelial growth reduction in Fusarium oxysporum [22] and S. sclerotiorum [20]. However, in our study we demostrate that this compound is also released by LB media. In this sense, it is not necessarily a true bacterial VOC, which emphasizes the importance of TICs subtraction, which is not commonly done at literature thus far.

Phenylacetonitrile has been reported in the volatile microbial database (mVOC) as a metabolic product of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [23].

This aromatic compound has a nitrile moiety, which is a functional group widely distributed among fungicides such as benomyl (methyl-1-(butylcarbamoyl)-benzimidazol-2-yl-carbamate) and chlorothalonil (2,4,5,6-tetrachlorobenzene-1,3-dicarbonitrile). Faced with possible positive results of the use of phenylacetonitrile as a compound with antifungal activity against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B, it would be necessary to study its mechanism of action and the convenience of its use in the field of sustainable agriculture, since this compound poses a toxicity hazard (R22, R24, R26).

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that VOCs mediated interactions between bacteria and fungi occur in four out of eight Paenibacillus strains tested here, which are active as fungi controller in an in vitro test. The strain PNM-50 (Paenibacillus ehimensis NBRC15659) is demonstrated to be the most active one against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides 26B based on a significant reduction in the radial growth and in the stimulation of spore germination.

Our results were consistent with previous studies suggesting that the VOCs emitted by bacteria depend on the growth medium [24]. In addition, it becomes clear this field of volatile compounds needs to be studied much more thoroughly: In past research several reported bacterial VOCs actually turned out to be by-products of the culture media sterilization process, but were falsely classified as bacterial metabolic products. It is important to analyse not only the head space of cultured bacteria but also those of culture media for reference (blank).

The compounds tentatively identified at headspace of PNM-50 cultured on LB media were 2-furanmethanol, phenylacetonitrile, undecanoic acid, and 2,4-dimethyl pentanol, the quantities of which depend on the incubation period.

VOCs from Paenibacillus could be used as pesticides and fertilizers, being an open-field to provide new sustainable and eco-friendly alternatives to conventional agents. Among our putatively identified compounds only phenylacetonitrile was previously reported to exhibit antifungal activity, whereas the other three are new candidates. Future research must therefore identify the assigned putative compounds by using standards to compare the chromatography peaks and by carrying out agrochemical safety tests before implementation in field applications.