Introduction

Assessing and quantifying rural development is a complex and challenging task. Several circumstances define its complexity. Firstly, rural development problems have been approached separately, based on a disciplinary point of view (Ellis & Biggs, 2001); secondly, rural development difficulties have been beyond the capacity of governments to deal with them (Kay, 2005). Thirdly, many of the beneficiaries of rural development policies have remained isolated from the spaces where the decisions are made (Van der Ploeg, 2013). Finally, the understanding of the significance of rural development, and hence the best way to reach it, have caused huge disagreements among the stakeholders involved in these struggle (Chambers, 1983; Scoones, 2015).

Regarding the understanding of rural development, it has been focused mainly on an economic perspective, which privileges the economic activities of rural areas (Bernstein, 2010; Pachón, Bokelmann & Ramírez, 2016a). Consequently, the rise of agricultural production has been the way to increase rural incomes and hence rural development (Bryceson, Kay, Mooij & Barkin, 2004). However, the prominence of social and environmental concerns in the rural development debate is currently accepted by many more stakeholders involved in the rural development analysis (Desmarais, 2008; Patel, 2009; Roberts, 2008). The method analysed in the current paper defines rural development as the process to improve the quality of life for all rural inhabitants while ensure that their rights are respected.

The rural development approaches have evolved from a limited view based on a disciplinary focus, to a transdisciplinary emphasis where more relationships among all the challenges of rural development are taken into consideration (Scoones, 2009). For instance, while the Modernisation of Agricultural Production was focused on the Green Revolution and the cutting edge of technology to increase production (Kay, 1998), Food Sovereignty emphasises the social recognition of rural inhabitants (Desmarais, 2002; Wittman, Desmarais, & Wiebe, 2010). In this context, it is important to define a different framework able to analyse the complexity of the countryside, as well as to identify the most critical challenges of rural development for the purpose of creating policies capable of overcoming those problems.

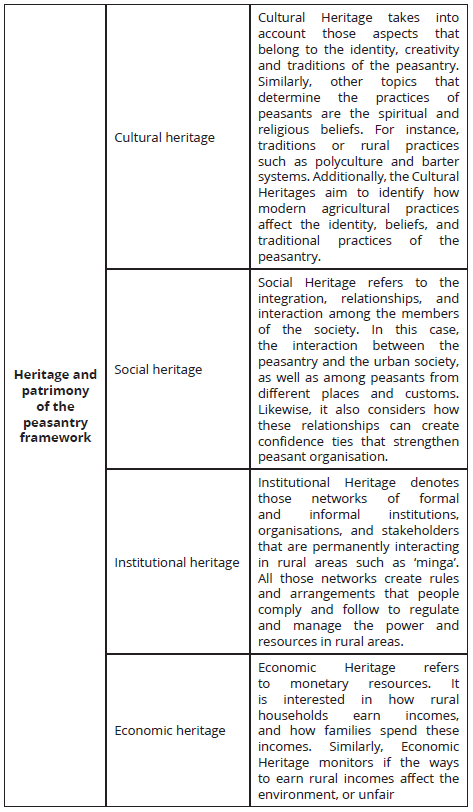

Heritage and patrimony of the peasantry, is a framework that includes the principal topics of the main rural development approaches. These topics are organised in seven heritages and patrimonies that the peasantry holds to improve its quality of life while ensure that its rights are respected. Initially, it is important to debate the meaning of heritage. A heritage is a network of knowledge, traditions, views, and practices that a society contemplates as vital for its history, identity and culture (Dormaels, 2012). Patrimonies are those structures, thoughts, and behaviours that the society obtains from its ancestors (Absi, Cruz, & Berkson, 2005). Based on these ideas, heritage and patrimony should be assumed in a similar way, and hence they should hold the relevance to be appreciated, protected, and promoted (Pachón-Ariza, Bokelmann, W, & Ramirez, Cesar, 2016b).

The patrimonies of the peasantry are seven: cultural, social, economic, natural, institutional, physical, and human, which are described in Table 1. Nevertheless, a crucial differentiation between capital and patrimony, must be examined. A capital is connected to the procedure of commercialising assets and commodities; hence capital belongs to the market scenario. In contrast, heritage and patrimony should be considered as part of the traditions, culture, and identity of the society. Patrimonies are priceless and impossible to commercialise. That is why the Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry framework no longer uses the idea of capitals (Pachón-Ariza et al., 2016b).

This paper seeks to ponder an alternative method to address rural development in a broad way based on the analytical framework ‘Heritage and Patrimony of the Peasantry’. For this purpose, analyses the results of six different regions in Colombia surveyed using a set of indicators selected through a comprehensive methodology. The current research represents a contribution to the analysis of rural development challenges, and hence, it is useful to all the stakeholders interested in those topics. For instance, for peasants because it is a way to identify their problems in a different form; for the government and policy-makers because it is a tool to identify aspects that can improve its practices to implement participatory spaces to construct public policies; and for students and academics because it is an alternative manner to address the studies of rural development from the conceptual and practical points of view.

Description of the process

Selection of indicators

Pachón-Ariza, Bokelmann & Ramírez (2015), describe deeply the Delphi Methodology used to select the indicators to analyse rural development in a broad way. The process used allows taking into consideration the perception of several factors by many stakeholders involved in rural development. Essentially, the methodology used starts with a literature review of a comprehensive range of scientific papers that permitted the selection of the first group of indicators, which were organised according to the conceptual affinity they had. Thereafter, a panel of experts assessed the indicators using the technique of the Vester’s Matrix. Afterwards the ‘critical indicators’ were selected. The next step was an online survey, where 190 people from 29 countries assessed the indicators according to the characteristics of a good indicator: reliability, feasibility, relevance, completeness, comparability, and sensitiveness. The results of the online survey were statistically analysed using the Principal Component Analysis. The final step was a pilot test of the indicators chosen. At the end of the process, 23 indicators remained. Figure 1, shows the seven heritages and their indicators.

Each issue was classified into three levels as follows: Low (1), Medium (2), or High (3) according to the answers of every interviewed. The level of the indicators was pondered according to the responses of the questions that belong to them. Consequently, the level of the indicators could be Low (1.0 - 1.66), Medium (1.67 - 2.32), or High (2.33 - 3.0).

Accordingly, the level of the Heritages is the result of the mean of the indicators that belong to every Heritage. For example, the level of the Physical Heritage is the outcome of the mean of Incomes, Entrepreneurism, and Infrastructure.

Selection of regions to apply the tool

Six different regions in Colombia were selected to apply the tool (Figure 2). The territories were chosen according to several categories: kind of agricultural production, distance to market places, infrastructure, and size of farms. Correspondingly, they were organised in three groups according to their similarities. In the first group are the regions of Arauca and Sur de Bolivar. The second group is composed by the territories of Santander and Gutierrez. Finally, the regions of Tundama and Gualiva constitute the third group.

The first region, Arauca and Sur de Bolivar, are territories characterised by isolation, because they are far away from important market places, and the infrastructure in general, is poor. For instance, the road network is mostly unpaved. Another important characteristic is the presence of illegal and legal armed forces that fight regularly, which means that violence is higher than in other places in Colombia. The fertility of the soils of these areas is low. However, both territories are rich in natural resources such as crude oil, water and biodiversity. Besides food crops, there is a significant presence of illegal crops. The common denominator of both territories is a limited presence of the government. In Arauca, 35 interviews were done, while 33 in Sur de Bolivar.

The second region, Santander and Gutierrez, are territories characterised by two important nearby marketplaces, Bogotá and Bucaramanga in the case of Santander; as well as Bogotá and Villavicencio in the case of Gutierrez. Despite these strengths, both regions remain fairly isolated because the roads in the neighbouring area of the cities selected (Florian and Gutierrez) are unpaved, which means the transport becomes strongly difficult and expensive during the rainy seasons. However, in the surroundings of these cities, there are some A-roads that connect to marketplaces. The agricultural production is mainly food crops, although livestock and bean crops are the representative productions of both areas. In Santander, 31 interviews were done, while 33 in Gutierrez.

Finally, the third region, Tundama and Gualiva, is characterised by an excellent infrastructure (highways and paved secondary roads) to access to markets, however, using it is expensive. The main market for both territories is Bogota, Colombia. Nevertheless, other places such as Tunja and Duitama in the case of the Tundama region, and Villeta and Facatativa in the case of the Gualiva territory are excellent market places. The production in Tundama is specialised in milk, even though it is a perfect place to produce food crops because it has the availability of irrigation. On the other hand, Gualiva that produces some food crops has a tendency to use the land for tourism. In Tundama, 39 interviews were done, while in Gualiva 36.

About the findings

This part of the paper analyses the findings that, in first place show big differences between the regions in some specific indicators, as well as similarities in other topics. In general, Biodiversity and Recycling were at a low level in all the six regions, while Communal Values was at a high level in all the territories.

According to Kreiger et al. (2013), recycling practices are uncommon in rural areas, and our findings based on the families interviewed confirm this statement. Some of the interviewed understand recycling as burning off all the residues, as well as burying or covering the waste with soil, especially plastic and cardboard. However, there are special cases such as the Parra family in the Gualiva region, who reuses plastics to make flowerpots. Jakus et al. (1997), explain the motivations of rural households to participate in recycling programmes, which are similar to the reasons why the families interviewed, consider recycling as important in rural areas. They remark that a proper disposal of the containers of fungicides and herbicides will avoid poisoning events. They remark the role of the government to collect all these containers because they do not know how to recycle, even though they have heard about it several times.

Concerning biodiversity, almost all the families answered that years ago their ancestors or themselves used non-commercial seeds. For instance, in the Tundama region, years ago peasants planted barley, and they sold their production to a company that made beer. However, for that company importing barley from Canada was cheaper when Colombia implemented the neoliberal policies, the border taxes disappeared, and the economy was open to the global market. Other traditional crops mentioned by the people interviewed in the Tundama Region as traditionally cultivated were the Andean tubers such as yellow and purple Oxalis tuberosa (oca), Ullucus tuberosus (olluco), and Tropaeolum tuberosum (mashua). However, just a few families plant these tubers nowadays. Aguirre et al. (2012), describe the current situation of these crops in that region, arguing that mainly the senior people planted and ate these tubers, young people do not know or eat them, and this calls the attention about the high risk of losing these tubers. Similarly, the interviewed mentioned that in the past it was possible to watch a lot of animals, but currently it is almost impossible. For instance, birds such as eagles and condors (Vultur gryphus), or other animals such as bears, foxes, and deer are rarely seen. They argue as the main reason for that situation that hunting was allowed years ago.

Regarding communal values, represented as solidarity in the questionnaire, got a high level among all the regions tested. The question was related to solidarity from neighbours when a difficult situation happened. Almost all the interviewed gave a high score to it because relatives and friends always have been alert to support when some natural disaster, bereavement, or illness affects other people. These findings correspond with Fafchamps (1992) & Skocpol (1982), who consider solidarity as an important characteristic of the peasantry.

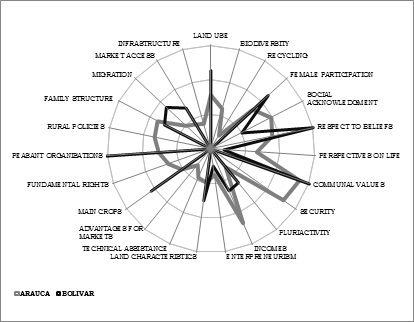

Arauca and Sur de Bolivar

As it was mentioned previously, both regions are distant from Bogota, the capital city of Colombia. According to Acosta & Bird (2005), even though the administrative decentralisation started since 1991, the disparities among regions in Colombia are evident, and that is exactly the case of Arauca and Sur de Bolivar. Figure 3, shows the results of all the indicators in both regions, where the area of Sur de Bolivar shows extreme results.

The infrastructure in both regions is really poor. Beyond the road infrastructure that is deficient, the most critical problem mainly in Sur de Bolivar is the electricity service. Around Ciénaga de San Lorenzo, the place where the information was gathered, there is no electricity service, while in Arauca in some rural areas the service is intermittent. Regarding other topics of infrastructure such as schools, communication, health centres, restrooms in the house, and clean water, the condition in Arauca is better than in Sur de Bolivar. It is remarkable that the transport network, especially in Sur de Bolivar, is virtually non-existent. The peasants interviewed must travel at least six hours by river to reach the market in a city nearby, which is the only alternative they have. However, it is exactly the same route they must use to have access to a health centre, bank branch, or a local government office. Obviously, it is an extreme case of isolation of rural areas in Colombia. Unfortunately, there are several examples like this.

That isolation determines a low level of other indicators. Galvis & Meisel (2010; 2013) explore a kind of ‘neighbourhood effect’ that creates poverty traps, which maintain a lag behind particular areas of Colombia, especially those located in the periphery and borders. This lag, beyond the economy, affects other topics such as fundamental rights. According to the interviewed in Arauca and Sur de Bolivar, the access to education, culture, information, and health centres, or old age pension is placed at a low level. The key point behind this low level, besides a poor infrastructure, is the few real incentives to rural inhabitants to access education, information, or culture because it does not imply an improvement in their quality of life. In other words, the priority of rural areas is surviving or getting a basic livelihood, instead of getting access to education, information or culture.

Along with the fundamental rights, the indicator perspectives on life, represented by topics such as the resting behaviour or alcohol consumption, was asked. Most of the peasants use to visit the city nearby to buy the basic groceries on sundays, because it is the common market day, and because it is the holiday for catholic people, that is the largest religion in the interviewed rural areas. The indicator additionally asks peasants about problems with alcohol consumption, and their answers are related to these problems on Sundays because it is the day to visit the city. Regarding this discussion, Páez & Posada (2015), argue that the risk of strong dependency in rural areas be higher than in urban ones, even though the consumption is lower in rural regions. However, the problem remarked by the interviewed is that the alcohol consumption, especially in men, is associated with domestic violence. Another question formulated was about the future of rural areas and the answers got a negative tendency, highlighting that current rural policies maintain the peasantry isolated and do not contribute to the likelihood to participate in the spaces where the decisions about rural population are made. Even though, since 1994 the ‘Municipal Councils for Rural Development’ were created to involve as many stakeholders as possible in the decision-making, and peasants as a central actor, they do not know about these Councils, as was mentioned by the interviewed.

The low level of the next two indicators, technical assistance and entrepreneurism, are related to the isolation described previously. Consequently, the peasants answered that they have not received technical assistance from the government for many years. Nowadays, they occasionally receive some technical advice from the sellers of agricultural supplies, but focused on the products they sell. The scheme of agricultural technical assistance was transferred in the process of administrative decentralisation from a national organisation called ‘Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario’ (ICA) to a municipal agency called ‘Unidad Municipal de Asistencia Técnica Agropecuaria’ (UMATA). Farah et al. (2004), emphasise in the fact that the UMATAS, as part of the decentralisation process, have played an important but limited role as a bridge between peasants and the municipal government. However, the lack of human and economic resources, as well as the influence of political interests does not offer a real solution for the technical assistance.

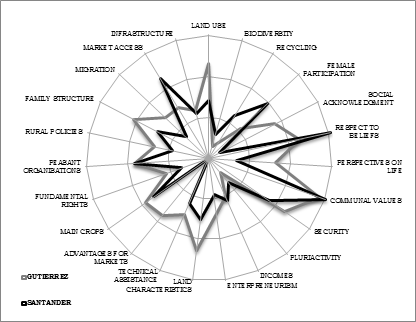

Gutierrez and Santander

The results remark that in both cases the majority of indicators are located at a medium level, Gutierrez shows more indicators at a high level than Santander, but less at a low level (Figure 4).

As it was mentioned before, both regions are located in the centre of Colombia, near Bogotá and other leading marketplaces such as Bucaramanga, Tunja, and Villavicencio. That means the isolation process described for Arauca and Sur de Bolivar is not evident in these regions, because they are close to the capital city of Colombia. However, there are topics such as the roads in the nearby of the places interviewed, that hold acceptable usability during the dry seasons, but not during the wet ones.

It is important to emphasise the problem of the transport network that affects these regions, as well as several secondary and tertiary roads in small Colombian cities. Even though the infrastructure was ranked at a medium level, the peasants from Gutierrez and Santander remark that the unpaved roads generate a kind of isolation to reach markets and to receive the benefits of the public services. That is why the Advantages for Markets indicator are qualified at a low level in Santander. Equally, the condition of the roads network hinders the access to the benefits of the beautiful landscapes and natural reserves in their surroundings.

Pluriactivity, is an indicator with a low level in both regions. Pluriactivity refers to family members working off the farm. Martínez (2010), proposes an interesting debate about pluriactivity, from the authors who believe that it is a representation of a rural crisis, to those who argue that it is an opportunity to get family incomes, however, calls the attention in the likelihood to change the rural traditions. dos Anjos & Caldas (2007), show two visions of pluriactivity according to the importance that the rural activity holds in the territories. When it is important, the incomes derived from the pluriactivity are spent to strengthen rural culture. On the other hand, when the pluriactivity is present in areas where rural activities are in crises, the rural culture is lost. This debate will be resumed later at the moment of the analysis of the economic heritage.

On the other hand, the indicator qualified at a high level in both regions was respect to beliefs. The interviewed think that their relatives and neighbours understand and show deference when someone expresses his/her ideas, even though these are different. It is interesting to find out a high level of this indicator in both regions that had a strong history of violence, especially during the decade of the fifties in the last century, where the main political parties faced each other in several rural areas, including Gutierrez & Florian (Guzmán et al., 1962).

The answers gathered in Santander show a possible contradiction between two indicators: Market Access and Advantages for Markets. The first one was qualified at a high level, whereas the second got a low level. The questions in the Advantages for Markets indicator are related to special products for the market. For instance, organic, green label, or post-harvest practices that add value to products. Poultry production is the main activity near to the cities of Puente Nacional and Barbosa, while sugar cane and blackberry are the principal ones near the city of Florian. None of the activities currently hold practices such as organic or green labels to add value to products. That is why this indicator was located at a low level. On the other hand, the questions related to the Access to Markets indicator are related to the place to sell the production, which is mainly on the same farm; the forms of payment that are usually immediate, and the habit of selling products along with the neighbours, in the case of blackberry.

Tundama and Gualiva

The regions of Tundama and Gualiva are located in the nearby of the important marketplaces. That is why the infrastructure, especially in motorways, schools, and bridges, even in rural areas is exceptional compared to the other regions analysed previously. Figure 5, shows the results of all the indicators in both regions.

It calls the attention that an indicator such as Advantages for Markets, in both regions got a low level. However, as it was discussed previously, the production of the peasants interviewed in both regions do not have any added value regarding organic production, green label or post-harvest treatment, despite the only mature cheese produced in Colombia, the Paipa Cheese, is made in the Tundama region. Additionally, it is important to remark that the availability of irrigation in this region generates exceptional conditions to produce good quality food such as vegetables, corn, or bulb onion. However, the main production in this area is livestock for milk production. The peasants answered that they had been specialising in milk production because that activity does not require much hand labour, which is scarce in the region. That situation goes along with the results of a low level of another indicator: Migration.

Migration becomes a challenge for rural areas. In some cases, migration is important especially for young people, because they acquired skills that in the future could be applied in their original rural areas and stimulate the economy (Stockdale, 2006).That is real when the migrants return to their original places at the end of the training, otherwise it becomes a drain of human knowledge that will benefit the places where the migrants finally locate (Taylor & Martin, 2001). Migration has both positive and adverse effects in rural areas. For instance, in the Tundama and Gualiva regions, the hand labour availability has decreased significantly, bringing as a consequence changes of productive activities from those that require more efforts to those that are less demanding in hand labour. Equally, the most evident consequence is the process of ageing of people in rural areas. Jurado & Tobasura (2012), added to the debate that migration generates a change in the recognition of the population as peasants, as they lose their identity as rural inhabitants; that means migration creates an ‘identity crisis’ among the migrant youth.

Pluriactivity is the other indicator graded at a low level. Pluriactivity is narrowly related to the challenge of migration. The questions of these indicators are related to the members of the family working off the farm and if that work is full or part time. The answers to these questions in both places are that all the families interviewed have at least one member working off the farm. Besides, it calls the attention that in Gualiva a lot of rural people are working in a new rural activity in the area: tourism. That area is located 80 km away from Bogotá, it has an excellent motorway, and its temperature is around 22°C, conditions that give this region the potential for rural tourism. Again, rural tourism shows a positive consequence because of the increased likelihood to get incomes for rural families. On the other hand, Gualiva holds a potential for food production because of the quality of the soils, water availability, and weather conditions. However, nowadays the pressure of tourism is changing the use of the land.

Considerations on the process and the findings

Analysis in the heritages and patrimonies of the peasantry framework

As it was examined previously, the analytical framework “heritages and patrimonies of the peasantry” takes into consideration seven kinds of heritages that the peasantry holds to improve their quality of life while ensuring that their rights are respected, in other words, to reach the best level of rural development. Figure 6, shows the level reached of each heritage for every region.

Cultural Heritage

Cultural Heritage takes into consideration the identity, creativity, and traditions of the peasantry, as well as political, spiritual, and religious beliefs. The results achieved in the indicators that belong to the Cultural Heritage in the six regions analysed locate this heritage at a medium level with a tendency to a superior border. Tundama shows the lowest level, and Sur de Bolivar, the highest.

Biodiversity, is an indicator that belongs to the cultural heritage and remains at a low level and all six regions. As it was described previously, biodiversity refers to the loss of traditional seeds and wild animals. According to Andrade (2011), and the information system of Colombian Biodiversity, 798 plant species and 269 of vertebrates are in danger of extinction in Colombia, that is why the peasants interviewed answered that they do not use some traditional seeds anymore. These seeds, such as barley, were a fundamental part of their diets, which means a loss of the rural identity and traditions.

Even though the female participation indicator was graded at a medium level in all the regions, it is remarkable that some of the women interviewed answered that they had been victims of domestic violence at any time of their lives. They recognise that years ago domestic violence was a common behaviour in all rural areas. However, several studies have documented that domestic violence, especially in the countryside in Colombia, remains a problematic situation (Defensoría del Pueblo Colombia, 2014; Iregui et al., 2015). The common denominator for domestic violence according to the interviewed is alcohol consumption, especially on weekends. That is exactly one example of a cultural behaviour, which also happens in urban areas, which should be overcome to improve the quality of rural life and respect the rights, in this case, of rural children and women.

Other indicators discussed previously, which belong to the cultural heritage, are respect to beliefs, common values and family structure. Precisely, family structure is composed of two questions. The first one is related to migration, a topic discussed earlier. The other subject was about the education level of the family members. According to the answers, all the interviewed are literate. Even though the education degree reached especially by peasants older than 40 years old is the primary school, all of them answered that can read and write. This topic is important regarding the cultural heritage of the peasantry because the interaction with the entire world is more unfavourable to illiterate people. Literate peasants can recognise the importance of their role in the society beyond food production, and hence recognise the cultural value of many of their practices and traditions.

Physical Heritage

Physical Heritage beyond infrastructure, which is crucial to reach rural development, analyses the availability as well as the access and use of this infrastructure. Barrios (2008), focuses on the importance of physical infrastructure of roads, drinking water, and irrigation systems to improve the quality of life in the countryside. However, the current analysis goes beyond and includes schools, bridges, health centres, electricity, paved roads, and transport network. It is important to remark that the mere existence of this infrastructure does not guarantee the improvement of the quality of life and the respect for the rights of rural people by itself (Shen et al., 2012). Accessing and using this infrastructure of schools or health centres adequately requires a sufficient provision of equipment and personnel to offer an excellent service. It also requires sanitation and education systems that allow people to receive a service with a similar quality to the one offered in urban areas.

Contrary to Cultural Heritage, Tundama reaches the highest level regarding Physical Heritage, and Sur de Bolivar the lowest. Taking into account this aspect, according to the Global Competitiveness Report 2015-2016, Colombia is ranked 84 among 144 countries on the topic of general infrastructure, 104 on the subject of transport infrastructure, 126 on the quality of roads, and 60 in relation to the quality of electricity supply (Schwab & Sala, 2015). According to Departamento Nacional de Planeación de Colombia (2016), just the 20% of the total Colombian roads are paved, and 6% of tertiary roads, which usually correspond to rural roads, are gravelled. Some of the reasons previously discussed explain why Colombia reaches that level, and hence the degree of this indicator in the current research. The explanation of the backwardness in infrastructure again is the isolation of some Colombian regions, especially the rural areas.

Physical heritage plays as well a fundamental role to improve the quality of life at a household level. For instance, the availability of restrooms at home, besides avoiding health problems dignifies peasants. In addition to that, the materials of the walls, floors, and ceilings and electricity of the rural homes, undoubtedly improve the quality of rural life (Ilskog, 2008). Reaching a proper level of that physical infrastructure at homes requires the participation of all the family at the moment of deciding how to spend the incomes, as well as if the household has the likelihood to spend its incomes in its welfare instead of paying loans, buying agricultural supplies, or alcohol consumption. Along with this, the participation of the family in new enterprises or new alternatives to get incomes, and the use of these resources to improve the physical infrastructure at home will result in a better quality of life.

Social heritage

Social Heritage denotes the integration of the peasantry to the society. The indicators of social heritage look to answer the question: how do these relationships can create confidence ties that strengthen peasant organisation? Initially, it is remarkable that according to the peasants interviewed, Social Heritage got a medium level in all the regions.

Social acknowledgement, as one of the indicators of social heritage, got a high level in some regions while a low in others. Two questions belong to the indicator. The first question asks about the equity of rural society in comparison to ten years ago. Some of the peasants that think that the current rural society is more equitable than before argue that nowadays there is more likely to work in agriculture because the services offered such as communication, transport, and television are much better, and also because there is less violence in rural areas than before. On the other hand, people who think that the current situation is worse argue that access to loans and technical assistance, as well as agricultural supplies, is more complicated and expensive than before. Furthermore, they emphasise in a situation analysed previously, which is migration. They argue that rural areas are being left alone and that just senior citizens are living there. The second question is about young people. The interviewed think young people are not proud of being peasants; they want to migrate and forget their ancestors. They do not wish to live like their parents, working in agriculture.

The results of the assessment of the indicators of Social Heritage are somewhat contradictory with the real Colombian rural life. In Colombia, as in many countries, the whole society owes the peasantry a social recognition of its importance (Machado, 2009). The agricultural activities have been in the imaginary of the society as something carried out by isolated, poor, and illiterate people. Even though 70% of the Colombian population lived in rural areas 60 years ago, violence by various actors has changed the map, and nowadays just 30% are living there (Mondragón, 2002). According to Norwegian Refugee Council & Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (2015), after Syria, Colombia was the second country in the world with the most internal displacements in 2015. 6’044.200 people have been forced to leave their farms and belongings. Many of these internal displaced are currently living in the surroundings of the main cities under conditions of extreme poverty. Violence, displacement, and isolation are a common denominator of many peasants in Colombia. Those who remained working on their farms were affected by conditions such as poverty and isolation that led to significant rural social movements against the government in 2013 (Grajales, 2015). Beyond the agreements to solve the requirements of those movements, the most notable achievement was the recognition by the entire society of the role of the peasants, and the general support of their requests (Valencia, 2015).

The isolation of some rural areas, as discussed before, affects the Fundamental Rights indicator, and hence the Social Heritage. Beyond education, culture, or information, it is significant to observe on a major challenge for rural people in the countryside, the access to an old age pension (Bohórquez-Caldera, 2013). The economic support for aged peasants mainly depends on their relatives, which have migrated to urban areas or remain working the agriculture, but in many cases with low incomes. The system of universal non-contributory pensions becomes an alternative to support rural people (Johnson & Williamson, 2006). Kakwani & Subbarao (2005), show evidence of the successful reduction of poverty in rural households in many countries using universal non-contributory pensions. However, a real solution to deal with this challenge is yet under construction, but beyond subsidies, it is important to include old peasants in a scheme that understands the conditions under which the Colombian peasants have been working the land.

Finally, to answer the question about peasant organisations, people were asked directly about the advantages of belonging to these organisations. The indicator got a medium level, and the answers show the meanings that these organisations have for the peasants. Several argue that they be good because they receive benefits from the government, while others think that they are the only possibility to survive. However, the idea that social organisations are dangerous remains in the imaginary of many people, which prefer working alone to avoid problems because of the history of violence in the Colombian countryside.

Institutional heritage

Institutional heritage encompasses official and informal rules that exist in rural areas to regulate relationships between people. In all the regions, Institutional Heritage got a medium level without big differences between them.

The indicators that belong to this heritage show how rural people try to overcome the challenges that normally they suffer. Security and hence violence are one of the indicators. As it has been debated, this is a huge problem in Colombian countryside, even though, according to the answers, security is ignored as an important problem in the regions interviewed. A possible reason for that perception is because the government since 2012 is involved in peace talks with the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC-EP) to achieve a consensual solution to the internal armed conflict that mainly rural areas have suffered for more than 50 years (Zerda-Sarmiento, 2016).

Strengthening communal values is the strategy used by peasants to overcome the consequences of the armed conflict. Interestingly, Communal Values was the only indicator that reached a high level in all the regions interviewed. Weldon (2006), describes the communal values such as solidarity, tolerance, and inclusion as the characteristics of the social movements to overcome violence and inequality. The peasants interviewed described solidarity as the method to overcome this long period of violence; equally, they argue that tolerance and inclusion have allowed them easy access to markets avoiding distortions, especially in regions where violence has been more severe.

Human heritage

Human Heritages of the Peasantry highlights the importance of the knowledge of the peasantry, transmitted over the generations. It notes the skills and abilities to tackle problems. Human Heritages of the Peasantry got a low level in all regions, which means that the traditional knowledge of the peasantry has been lost throughout the time.

Women have a crucial role in transmitting traditional knowledge among generations. That is especially true in rural areas because women share more time with children, and are in charge of their education (Nor et al., 2012; Smith & Akagawa, 2009). However, in the regions interviewed, the level of the female participation indicator was not high, although the answers about this topic remark that women are currently more respected than before, and nowadays they are taken into consideration at the moment of making decisions in the households. It could be explained because is common to find women as the heads of households in societies affected by armed conflicts (Galindo et al., 2009).

In this context, the perspective about the future of rural areas is ambiguous. According to the answers, the public policies are against the knowledge of the peasants because they try to impose production forms that ignore their traditions. Other reasons for this perception are due to migration and hence ageing; both aspects discussed earlier. An important topic remarked by the interviewed and mentioned before was that the entire society does not recognise the role and the significance of the rural areas. Besides, they emphasise in the aspect that the fertility of the soils has been lost because of the conventional cropping, instead of recovering the ancient ways of production.

Economic heritage

Economic heritage, refers to economic resources and how rural households earn and spend it. In all the regions, the economic heritage got medium level, excluding Sur de Bolivar where it got low level.

The indicators that belong to economic heritage have been explained before with the other heritages. However, it is interesting to remark that just a few of the interviewed have received some governmental subsidies; most of them special and transitory support to coffee growers. Regarding this topic, an example of the subsidies scheme of the Colombian government is the programme ‘Agro Ingreso Seguro’ (AIS) where the Colombian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development designed a strategy to support farmers between 2002 to 2010, to get ready for new free trade agreement with the United States. However, these resources ended up in the hands of people without any relation to the agrarian sector in a clear example of corruption (Mejía, 2012). In general terms, Colombia does not hold a strong programme of subsidies to support and protect its agricultural production (Coscione & Pinzón, 2014) .

Natural heritage

Natural Heritage highlights natural resources, the consequences of the productive practices, and their significance regarding the climatic change mitigation (Andrade, Rodríguez, & Wills, 2012) . The level of this heritage was medium with a low tendency. Interestingly, Sur de Bolivar shows the lowest level, even though it is the region with more natural resources available.

The results of the biodiversity and recycling indicators, were discussed previously. Furthermore, the land use indicator reached a medium-high level. According to the answers of the interviewed, they have different type of crops, which means that polyculture predominates, which is a characteristic of the peasant economy (Bebbington, 1999). However, there is a clear tendency to use the land for livestock production. On the other hand, they answered that practices to conserve the soil are uncommon; by contrast, adding chemical products to it predominates.

The Land Characteristics indicator, aims to identify the land use in accordance with the soil type. According to the perception of the interviewed, they are using the land appropriately. However, according to the report of GISSAT (2012), soils with a clear aptitude for horticulture production, are currently being used for livestock, especially in those areas that are closer to marketplaces and the migration is higher. Other soils close to protected areas are being used to plant illegal crops. As a result of the presence of these crops, both the biodiversity and inhabitants of these regions have suffered damages because of the fumigation scheme to eradicate those crops (Castro-Caycedo, 2014). Such kind of fumigation scheme indeed has a serious impact on all the heritages of the peasantry. It is simple to imagine that aerial application of glyphosate can have an impact on the entire life of the peasants, from the livelihoods to behaviours, from the health to traditions, because, after the application, nothing remains alive. Fortunately, Colombian government (2010-2018) decided to search alternatives to aerial applications.

An alternative to such problematic situation regarding the natural heritage is, first of all, to understand that this heritage belongs to the peasantry and through them, to the humanity. It is urgent to appreciate the real value that the natural heritage holds, just when this is appreciated, it can be protected and promoted to mitigate the effects of the climatic change. The peasants living there are in charge of taking care of that heritage on behalf of all the humanity. Then humanity must provide the conditions for them to live and protect such precious heritage.

Summing up, in general terms, the Heritages and Patrimonies of the Colombian Peasantry are at a medium level, which means that public policies have an important likelihood to create the conditions to improve all these indicators, especially in isolated places such as Sur de Bolivar or Arauca.

Final considerations

This paper aimed to ponder an alternative method to address rural development in a broad way based on the analytical framework ‘Heritage and Patrimony of the Peasantry’. It was the first application of both, the indicators and the analytical framework. That is why the current study represents a contribution to the analysis of rural development challenges, and hence, it is useful to all the stakeholders interested in those topics.

The analytical framework heritages and patrimonies of the peasantry, its indicators, and its application in Colombia, are a new way to address a ‘Wicked Problem’ such as rural development. Undoubtedly, a broad vision to cover rural development in a more holistic way becomes a contribution to tackle as many aspects involved in the improvement of the quality of life and the respect for the rights of rural inhabitants as possible. A transdisciplinary approach used both, to define rural development indicators and the Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry, is a way to overcome the particular point of view that focuses on specific problems ignoring the complexity of rural development.

The current analytical framework and its application cover several challenges involved in rural development, as well as a way to analyse those challenges. That is why Heritages and Patrimonies of the Peasantry opens the door for all the stakeholders interested in rural development analysis such as governments, researchers, students, and peasants to approach all these problems taking into consideration the indicators selected. An advantage of the current methodology is that it takes into account the meanings of many stakeholders, for that reason several aspects are included. However, that advantage must be tackled in an adequate manner, establishing all the relationships that all these topics hold. Otherwise, understanding the real complexity of rural development challenges would be tough.

Taking a wider picture of rural development is possible when the outsiders involve the peasantry. That is another contribution of the current analytical framework. For that reason, this proposal could become a useful baseline in the future to evaluate the incidence of public policies in rural regions.

However, as this is the first application of the framework and its indicators, a deep statistical analysis is necessary for future research for the purpose of establishing future analysis among territories, or in the same territories in different moments. In other words, the current paper aims to describe by the first time the framework and its usefulness in order to understand and address rural development, but next applications are important to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the indicators and their relationship with the heritages, and then improve the entire proposal.

Official information regarding rural areas is difficult to get in several developing countries. Besides, gathering this information in a research project becomes a complex task due to funding limitation and access to isolated areas. The current research has collected information in Colombian regions such as Sur de Bolivar or Arauca where access is difficult. That is why this information is a baseline, based on the perception of the peasants, and then complementary studies with different methodologies are crucial to compare with the current results, and hence have a complete picture of the reality