Introduction

Airway-related problems are the most common perioperative complications in pediatric anesthesia. Incidences in the literature are as high as 53% in children taken to non-cardiac procedures under general anesthesia,1 resulting in higher perioperative morbidity and mortality. In fact, Bhananker et al reported that out of 193 cardiorespiratory arrests occurring in children under 18 years of age between 1998 and 2004 in the United States, 49% were anesthesia-related and, of those, 27% were associated with airway complications, laryngospasm being the main cause (6%).2 Moreover, it has been documented that, in itself, the treatment of this condition may actually increase postoperative morbidity.3-5

Growing interest has emerged recently regarding the potential association between this outcome and the type of device used for securing the airway during anesthesia. Although the endotracheal tube (ET) is considered the standard device for airway management, it has been found to be associated with an increased incidence of laryngospasm,6 apparently as a result of direct stimulation on the larynx and the trachea.7

The increasingly frequent use of the classic laryngeal mask (LM) in pediatric anesthesia led to consider that it would remove the main trigger of laryngospasm and that the incidence of this complication in the pediatric population would improve. However, 3 prospective studies8,9 have not found a difference in the incidence of laryngospasm between the 2 devices; and, in contrast, 2 retrospective studies1,3 showed an increase in this complication with the use of the LM as compared with the use of ET in children.

In view of these contradicting findings and bearing in mind the absence of any prior clinical trials, a non-inferiority clinical trial was undertaken with the aim of determining the risk of developing laryngospasm with the use of ET versus LM as methods for securing the airway in a pediatric population taken to surgery under general anesthesia in a referral healthcare centre in the city of Medellin, Colombia.

Methods

Study design

Non-inferiority, single-blind, controlled clinical trial of parallel groups with 1 to 1 random assignment. The study was submitted for evaluation and approval by the bioethics committees of Antioquia University and San Vicente Fundación University Hospital in Medellín, Colombia, through approval certificate No. 009 of June 7, 2018.

Study subjects

The study population included children 2 to 14 years of age, American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification I to III, scheduled for elective surgery under general anesthesia in the San Vicente Fundación University Hospital, whose parents agreed to their participation in the study. Excluded were patients going to head and neck, thoracic, or abdominal surgery; positions other than supine decubitus; surgeries of more than 3hours; high risk of aspiration such as gastrointestinal bleeding, gastroparesis, and gastroesophageal reflux; difficult airway criteria; and anticipated mechanical ventilation in the immediate postoperative period.

Interventions

Patients were assessed in the pre-anesthetic preparation area and following a medical history and verification of compliance with eligibility criteria, the patients and their parents were invited to participate in the study, and the informed consent was signed.

In the operating room, basic ASA monitoring was instituted (electrocardiogram, capnography, oximetry, and non-invasive blood pressure measurement) and anesthetic induction was performed either with inhalation agents, intravenous, or mixed anesthesia, depending on whether the subject arrived with a peripheral or central access line, and in accordance with the anesthetist's preference regarding the use of opioids and nitrous oxide.

In general, doses used for intravenous induction were the following: fentanyl 1 to 2 µg/kg, lidocaine 1 mg/kg, propofol 2 to 5mg/kg and dexamethasone 0.15 to 0.2 mg/ kg. For inhalation induction, 6% sevoflurane was used in oxygen flow mixed or not with 50% nitrous oxide, fentanyl 1 to2 µg/kg and dexamethasone 0.15 to 0.2mg/kg.

Later, the patient was assigned to 1 of the 2 groups: LM, Laryngeal Mask Device (LMA Classic Airway, Teleflex Medical Europe Ltd, Dublin Road, Westmeath, Ireland); and ET (Well Lead Oral Endotracheal Tube, SSEM Mthembu Medical Ltd, Wynberg, Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa) (Kendall Carity, Well Lead Medical, Medite), assigning the size and use of the balloon cuff according to age.

Outcomes

The main outcome was laryngospasm, clinically manifested in the form of inspiratory or expiratory stridor, absence of respiratory sounds, and paradoxical thoracic/ abdominal movement.

The secondary outcomes were: arterial desaturation lower than 90% and bardycardia, defined as heart rate below the 5th percentile for the age; additionally, any other related complication was assessed, for example, cardiac arrest and death.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the method described by Christensen10 for non-inferiority clinical trials, taking as a basis an expected incidence of laryngospasm of 12% in both groups, which is the mean incidence reported by Bordet et al,7 and is the annual incidence standard in the healthcare center where the study was conducted.

In addition, a 10% non-inferiority margin between the 2 interventions was considered. With these data and an alpha error of 0.05 and 80% power, a sample size of 130 patients per group was obtained, for a total of 260 patients. Given the type of intervention, no losses to follow-up were considered.

Randomization

The random sequence was generated by an outside research assistant, using the RADN (Random Number Generator Software; Steven Piantadosi MD, Ph.D, Jhons Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, Maryland, United States) software package by means of variable-size block permutations (4, 6, and 8). The sequence was veiled using numbered opaque sealed envelopes, opened by the treating anesthetist once the patients met the eligibility criteria.

Blinding

The study was blinded for the patient and for the person in charge of determining outcomes. Given the nature of the intervention, blinding of the anesthetist who performed the intervention was not possible, Once the treating anesthetist introduced the device in the airway, a second anesthetist, blinded to the intervention, made the clinical assessment of the presence of the outcome during induction, maintenance and, postoperatively, once the device was removed. Blinding to the intervention for the second anesthetist was maintained by means of the use of the screen to block viewing of the device on the patient's face.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the subjects were described as frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables, and as central trend and scatter for quantitative variables. Normality for quantitative variables was analyzed using the Olmogorov-Smirnov test. Normal variables were reported as means and standard deviation; non-normal variables were reported as means and interquartile ranges.

Proportion differences in the 2 groups were evaluated for the laryngospasm endpoint and the Chi square test was used to determine statistical significance. Each result was reported with its respective 95% confidence interval (CI) and P value, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No subgroup analyses or interim goodness analysis were performed. Per protocol and intention to treat analyses were performed. All the analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS 20.0 software package (IBM SPSS Statistics; IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, United States).

Results

During the patient recruitment time period between October 2013 and May 2014, 934 patients were evaluated for selection and, of them, 270 were randomized to participate in the study (Fig. 1). One patient in the ET group had to be taken, intubated, to the intensive care unit due to perioperative complications not related to anesthesia, and 1 patient assigned to the LM group had to be intubated due to poor ventilation resulting from leaks in the device.

Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Characteristically, the majority of the patients in the study were healthy patients (62.2%) taken to orthopedic surgery and pediatric surgery (58%). There was a personal history of prior respiratory infections in 21% of patients and of passive cigarette smoking in 28.5%.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study.

ASA=American Society of Anaesthesiology, SD=standard deviation.

* Exhibit normal distribution.

Source: Authors.

The anesthetic management of the patients taken to different surgical procedures is described in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Table 2 Anesthetic management of the patients enrolled in the study.

N2O=nitrous oxide, SD=standard deviation.

* Chi-square test with a P<0.0001.

Source: Authors.

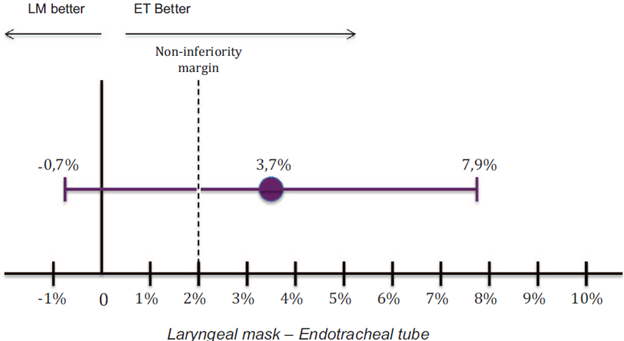

Laryngospasm occurred in 3.3% of all patients evaluated; 7 patients (5.2%) in the LM group, and 2 patients (1.5%) in the ET tube group developed laryngospasm, with a difference in risk of 3.7%, 95% CI (-0.7% a 7.9%), and a P value of 0.147 (Fig. 3). The per protocol analysis did not reveal any difference as compared with the results of the intention-to-treat analysis.

Source: Authors.

Figure 3 Laryngospasm, LM vs. ET (proportion difference and 95% confidence interval). LM=Laryngeal Mask; ET=Endotracheal Tube.

The majority of laryngospasm cases occurred during emergence from anesthesia (85.7%). No statistically significant differences were found for the other outcomes evaluated (Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, laryngospasm occurred in 3.3% of the children taken to surgical procedures under general anesthesia. This incidence is within the ranges published in previous studies, which vary between 0.04% and 14%.7,11,12 Due to incidence found was much lower than the reported in the same institution, the authors decided to modify the non-inferiority margin by using the synthetic method,13 which allows to establish the margin according to the data thrown by the study and the clinical judgment of these. In this case, it is decided to generate a delta of 2% (see Figure 3). According to the above, and taking into account the incidences difference between them was 3.7% with a 95% CI(-0.7 to 7.9%), it cannot be declared non-inferiority between the devices used, laryngeal mask and endotracheal tube. Additionally, and given that the confidence interval crosses zero, it is not possible to declare superiority of one device over another (see Figure 3). These results show consistency when intention to treat or per protocol analyses are performed, the latter being the right analysis to declare non-inferiority of 1 group compared with the other.13

In terms of the other outcomes, no difference was found for the main complications derived from the development of laryngospasm, including bradycardia or oxygen desaturation. However, it is important to report that one of the patients in the LM group went into cardiac arrest due to sustained bradycardia, but with no fatal outcome or secondary neurological complications. This single finding does not allow to arrive at conclusions of superiority of 1 group over the other in terms of morbidity.

Our study found that more than half of the cases of laryngospasm occurred upon awakening, while the remaining were divided equally between induction and maintenance. These results are in contrast with a case-control study in pediatric patients which found a greater frequency of laryngospasm during anesthesia induction.14 When the ET was used, laryngospasm occurred more frequently upon awakening, while with the use of the LM, it occurred more frequently during induction or maintenance.15 It may be that the highest risk moment depends both on the anesthetic technique as well as on airway management.

Another striking aspect of our results is that the incidence of this outcome is far lower than expected, even much lower than the range of 15% to 7% found in this type of population in our hospital, where staff in training participate quite actively in the management of the pediatric airway (Fig. 2). This situation may be attributed to 2 possible explanations: the way the airway was managed, in particular during emergence from anesthesia, when the recommendations for this setting were used in the majority of patients: ET removal with the patient fully awake, and removal of the LM with the patient still asleep but under spontaneous ventilation (Table 2).16-21

In fact, this hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that the 2 patients in the ET group who developed laryngospasm did so while still asleep, and 5 of the 7 patients of the LM group developed laryngospasm long after emergence. A second explanation, very much related to the first one, is the potential Hawthorne effect of the treating anesthetist or student.

The blind, randomized design of this study is one of its strengths, considering that it allowed control of some confounding factors such as a history of acute infectious or chronic respiratory disease and patient exposure to cigarette smoking. In addition, several concomitant interventions were controlled from the beginning of the exposure to the evaluated factor (Tables 1 and 2). Another aspect worth highlighting is that the age range described in the inclusion criteria and the multiple surgical procedures evaluated allow extrapolation of these results to a large proportion of patients in the common pediatric anesthesia practice. Finally, the sample size, although it may have been small for the incidence found, is among the largest reported in the literature for these types of studies.

The study has several limitations, the most important being that the incidence found was much lower than expected. This result may lead to an oversized difference between the 2 groups based on which the adequate non-inferiority margin was determined, without disregarding the fact that a difference between the 2 groups as low as 3.7% may eventually be sustained in larger studies. For this reason, a study with a larger sample size may be required to demonstrate this difference. This study being a perioperative management study, it has the additional limitation of the inability to blind the treating anesthetists, which may explain the results. Finally, the study was conducted in a level IV university hospital where perioperative management may be different than in level II or III hospitals that serve this type of population. Consequently, our results may need to be confirmed in a multicenter study with a wider range of pediatric clinics and hospitals.

Conclusion

This study did not show that, in pediatric patients taken to surgical procedures under general anesthesia, airway management using LM is not inferior or superior to the ET in terms of the occurrence of laryngospasm. Greater morbidity or mortality secondary to the use of either of the devices used was not demonstrated. A larger sample size study may be needed to confirm non-inferiority in the outcomes studied.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to doctors Carolina Rodríguez, Eliana Castañeda Marín, Diomer Avendaño, Lacides Moscote, Andrés Barrios for their participation in data collection and synthesis.

Anaesthesiology Group of Hospital San Vicente Fundación who facilitated the research and participated in its development.

Ethical responsibilities

Human and animal protection. The authors declare that the procedures used in the study followed the ethical standards for responsible human experiments and were in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare having followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding patient data disclosure.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects reported in the article; the form is kept by the corresponding author.

text in

text in