INTRODUCTION

Penile cancer is one of the less frequent urologic tumors, accounting for 2-3% of male urogenital tumors; in 95% of cases, it is a squamous cell carcinoma 1. Incidence tends to be higher in developing countries and it is associated with risk factors such as poor hygiene, smoking and infections such as human papilloma virus infection 2. It is usually a slowly growing tumor that spreads mainly through the lymphatics and requires surgery as standard treatment. Surgery consists of total tumor resection, attempting to preserve as much length as possible of healthy tissue that is functional for micturition and maintenance of sexual contact. Radical penectomy (RP) with perineal urethrostomy is performed in those cases in which the resection level is such that it preempts this goal 1.

Radical penectomy is infrequently performed and has precise indications which are increasingly the subject of controversy considering that meatal preservation is critical for quality of life 3. However, recent reports claim that RP is the main form of treatment in 15-20% of primary penile cancers 4.

There is scant information regarding anesthetic and perioperative considerations related to this surgery, coming from isolated case presentations or in the form of extrapolations from penile prosthesis implant surgery. Some of the perioperative issues associated with RP include significant acute postoperative pain, bleeding, surgical wound infection and mood disorders 5-8.

We present the case of a patient with coronary heart disease and a psychiatric condition who presented with advanced, overinfected, penile cancer and underwent radical penectomy using a combined spinal-epidural (CSE) technique. The patient received intraoperative transfusion and was followed up by the pain team on a daily basis.

CASE REPORT

A 65-year-old patient with a history of hypertension, non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus type 2, dyslipidemia and percutaneous coronary revascularization with two stents performed 5 years before, on treatment with enalapril, metformin, bisoprolol, rosuvastatin and aspirin. Surgical history included appendectomy and vasectomy, with no reported incidents during anesthesia. The patient was functional class I and a preoperative echocardiography performed 4 months before showed good global and segmental systolic function. The patient signed the informed consents for surgery and anesthesia and gave his permission for photographic documentation. Approval was obtained from the Scientific Ethics Committee of Admiral Nef Naval Hospital (July 2017).

The patient presented in July 2017 with a penile tumor. The incisional biopsy performed under local anesthesia showed a well differentiated, eroded and infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma. However, the patient refused surgery and chose alternative medicine therapies. In August 2019, the patient presented with stabbing and burning genital pain, grade 4 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and findings of purulent secretion and enlarged glans (Figure 1), fever and altered general status. Significant results of the laboratory tests performed on admission included Hb of 7.2; creatinine 1.73; increased inflammatory parameters (C-reactive protein and leukocyte count), hyperglycemia, and inflammatory urine sediment with abundant bacteria. The approach to management was antibiotic therapy, hematocrit optimization with red blood cell transfusion and compensation of pre-renal failure and diabetes. The patient was also found to be anhedonic and emotionally labile and was diagnosed with major depressive disorder which was treated with citalopram. One week after admission, the patient was scheduled for surgical resection of a stage IIIB penile cancer, T3N2MO, in two stages: 1) radical penectomy and 2) bilateral inguinal lymphadenectomy (with a 1-month interval), due to the existing infectious compromise.

The preoperative physical examination showed preputial edema preventing glans coverage, together with a hard mass adjacent to the base of the penis (Figure 1). Additional workup included a bone scan which showed no evidence of secondary bone involvement, and computed axial tomography (CT scan) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis that revealed the penile mass already described plus bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy. Pain was classified by the pain team as somatic and neuropathic based on a pain score of 4 using the DN4 questionnaire (Table 1) for burning genital pain. Pregabalin at a dose of 75 mg/day was initiated five days before the surgery.

TABLE 1 DN4 Questionnaire. of the penis.

| Parameter | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Question 1: Does your pain have one or more of the following characteristics? |

1. Burning 2. Painfulcold 3. Electric shocks |

1 1 1 |

| Question 2: Is the pain associated with one or more of the following symptoms in the same area ? |

4. Tingling 5. Pins and needles 6. Numbness 7. Itching |

1 1 1 1 |

| Question 3: Is the pain located in an area where the physical examination had one or more of the following characteristics? |

8. Hypoesthesia to touch 9. Hypoesthesia to pricks |

1 1 |

| Question 4: In the painful area, can the pain be caused or increased by: |

10. Brushing | 1 |

| Patient score: /10 | ||

Every positive response is assigned 1 point and every negative response is 0. Points are added and if the total score is equal to, or greater than 4, pain is classified as neuropathic.

SOURCE: Adapted by the authors from Bouhassira 9.

Every positive response is assigned 1 point and every negative response is 0. Points are added and if the total score is equal to, or greater than 4, pain is classified as neuropathic.

On arrival of the patient at the ward, monitoring was established with electrocardiography (EKG), heart rate (HR), non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) and pulse oximetry (SatO2). Two peripheral venous accesses (# 16 and # 18) were established uneventfully. With the patient in the sitting position, a combined spinal-epidural anesthesia technique was used at the L3-L4 space using a #16 peridural catheter and a long #27 catheter for the spinal component after infiltrating with 2% lidocaine, with injection of 12.75 mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine and 15 μg of fentanyl. The peridural catheter was then fixed at 12 cm. The setup time was 16 minutes. The patient refused sedation.

With the patient placed in modified lithotomy position, radical penectomy (sectioning both corpora cavernosa) was then performed, leaving a perineal urethrostomy (Figures 2,3 and 4).

SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 3 Surgical wound after radical penectomy with perineal urethrostomy and Jackson Pratt surgical drain.

SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 4 Surgical specimen of penile cancer arising from the balanopreputial sulcus and infiltrating the fascia, tunica albuginea and tunica dartos, corpora cavernosa and periurethral spongy tissue.

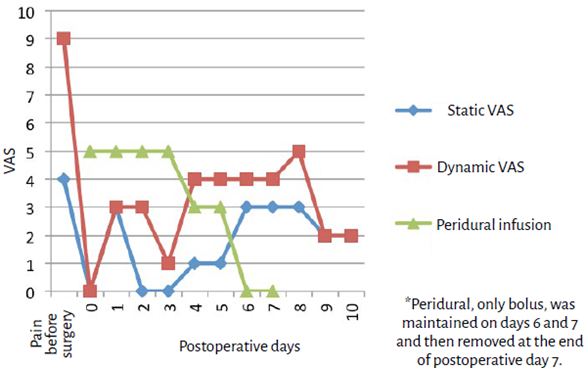

The patient received tranexamic acid, ephedrine 6 mg, magnesium sulphate 1.25 g and paracetamol 1 g, plus antibiotic therapy according to schedule. Two units of red blood cells were transfused due to blood loss of approximately 700 cm3. Surgical time was 115 minutes. The patient was transferred to the step-down unit for postoperative recovery, with the following vital signs on arrival: BP 114/74, HR 67 and 98% ambient Sat02, no fever and a score of 0 on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The patient had a stable course over the next few days, with static and dynamic VAS pain scores of 1 and 2 (average during the first 96 hours), respectively, treated with peridural patient controlled analgesia (PCA) consisting of 0.125% levobupivacaine initially set at 5 (mL/h infusion), 5 (mL bolus as required by the patient) and 20 (20 minute block). Additionally, paracetamol, pregabalin and citalopram were also used. The VAS and peridural infusion data are shown in Figure 5. Because of high daily requirements (average demand of 35 boluses per day, with 25 administered), the peridural catheter was left in place for seven days, with a good response as shown by a daily VAS score < 2. After peridural PCA removal, pain increased to 4 on the VAS, requiring the administration of intravenous analgesia and an increased dose of pregabalin. Because of the development of surgical wound infection, the patient received 10 days of antibiotic treatment with amikacin and was seen on a daily basis by the psychologist due to exacerbation of his psychiatric condition. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 16 with a score of 1 on the VAS and a score of 2 on the DN4.

VAS: Visual Analog Scale. SOURCE: Authors.

FIGURE 5 Pain assessment 10 days after RP and peridural infusion.

After a one-month interval, the patient was brought back for bilateral lymphadenectomy, again using the CSE technique, with good postoperative course, removal of the peridural PCA on the second postoperative day and discharge after 7 days. The patient was later started on radiotherapy.

Monthly follow-up was indicated with the participation of a multidisciplinary team consisting of psychiatry, urology, and pain clinic. Treatment was maintained with citalopram 20 mg every 12 hours, pregabalin 150 mg every 12 hours and paracetamol 1 g every 8 hours, with good postoperative course, improved mood and sleep, and a VAS of 2.

Twelve months later, the patient presented with fever and hypotension associated with a painful mass in the right thigh; a CT scan of abdomen and pelvis revealed a relapsing pelvic mass, bladder metastasis and iliac and periaortic lymphadenopathy. The patient and the family declined any future interventions and decided on referral to palliative care. Pregabalin was maintained and the patient was started on the use of buprenorphine patches. The patient died two months later at home.

DISCUSSION

Radical penectomy has a profound impact on the patient's psychological condition, sexual life and quality of life, as illustrated by this case of a patient who suffered from anxiety disorders and depressive syndrome 10. Table 2 summarizes the perioperative considerations with their respective strategies derived from different clinical cases used in this report.

TABLE 2 Perioperative considerations in radical penectomy with corresponding strategies.

| Considerations | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Acute severe postoperative pain | Multimodal analgesia, prefer regional or combined techniques |

| Surgical nerve injury, risk of chronic post-surgical neuropathic pain | Daily follow-up by pain unit and avoid early removal of peridural catheters. Multimodal analgesia/regional technique |

| Profuse bleeding | Large venous accesses, reserve of blood products, individualized transfusion. Tranexamic acid. |

| High incidence of surgical wound infection | Broad spectrum antibiotic therapy. Multimodal analgesia. |

| Concomitant psychosomatic disorders | Psychiatric assessments, family support and pharmacological treatment. Multimodal analgesia. |

| Perineal urethrostomy stenosis | Regular nursing and urology follow-up. |

SOURCE: Adapted by the authors from Savu et al., 5; Yadav et al., 6; Reinstatler et al., 7 y Croll et al. 8.

The penis has a rich blood and nerve supply. Nerves frequently involved in penile pain are afferent nerve endings in the skin, glans, urethra and corpora cavernosa. The main nerve blocks for penile surgery focus on the dorsal nerve of the penis, the pudendal nerve and the sacral roots 7. The use of low lumbar CSE helps block those roots and treat pain at the point of origin. Moreover, patients who received regional anesthesia for penile surgery described less postoperative pain and required less opioid use when compared to patients who received general anesthesia 11.

Acute postoperative pain is the most frequent preoperative concern for the patients 12, because, if not treated adequately, it may become chronic. Post-surgical neuropathic pain is a highly underestimated clinical problem. It is estimated that it can be as high as 10% in oncologic surgery, urologic surgery accounting for many of those cases 13. Probably due to perineural permeation and infectious involvement, this patient reported preoperative pain, with the subsequent risk of chronic post-surgical pain, which is consistent with urologic surgery studies that report prior pain in 20% of patients 14. Other risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain are pre-existing emotional distress, prior opioid use, previous surgery in the same site, and acute postoperative pain 15. Two of these factors (pre-existing pain and emotional distress) were present in this patient. Moreover, RP requires nerve sectioning, another factor that has been implicated in the development of chronic pain 15. Therefore, the anesthetist plays a critical role in pain prevention and management following RP, given that prophylactic strategies are more cost-effective than allowing the pain to become persistent. In this case, the technique used were:

Peridural analgesia. By minimizing signal transmission to the spinal cord, nociceptive transmission to the dorsal horn can be prevented, avoiding central sensitization 15 . Regional techniques have been shown to reduce the risk of chronic post-surgical pain in thoracotomy and breast surgery 16 . Also, spinal anesthesia has been found to reduce the incidence of post-procedural chronic pain in cesarean section, when compared to general anesthesia 17. Although evidence is lacking in RP, the mechanism of chronic pain reduction could be assumed to be similar. In this patient, the use of a peridural catheter contributed to a faster recovery, better control of the psychiatric disorders and higher satisfaction. It also helped diminish surgical wound infection through modulation of the inflammatory response to the surgery and improved tissue oxygenation 18.

Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid that acts on presynaptic calcium channels. Good quality studies have shown that its preventive use may reduce chronic post-surgical pain 15.

As part of multimodal analgesia, magnesium sulphate and paracetamol contribute to a shorter length of stay and opioid sparing, with the resulting reduction of opioid-related adverse effects 19. Magnesium sulphate is an N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptor antagonist, therefore playing a key role in the management of postoperative pain and hyperalgesia as it reduces hyperexcitability and sensitization15. Moreover, this patient was not a candidate for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because of the history of renal failure.

Psychosocial factors. Pharmacological treatment and psychotherapy to optimize sleep and mood before the surgery contributed to a good recovery in this patient.

Following major urologic surgery, pain on the second postoperative day is described with a score of 4 on a scale of 0 to 10 which gradually drops to 1 after 6 months, with close to 2% of patients using oral opioids 15. Although there is a paucity of reports on VAS scores after RP, the assumption is that the situation could at least be similar.

As far a survival after RP is concerned, because it is mostly performed in patients with advanced-stage disease, more than 40% will die within the first 5 years, while 60% will relapse 4,20. This patient was no exception because he died one year after the surgery. However, despite this unfavorable outcome, individual case reports like the one described in this paper shed light on perioperative considerations and intra and postoperative pain management that can serve as a basis for the development of recommendations based on further larger scale studies.

ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

Approval by the Ethics Committee The Scientific Ethics Committee of Admiral Nef Naval Hospital granted approval in July 2017.

Human and animal protection The authors declare that no human or animal experiments were conducted as part of this research.

Data confidentiality The authors declared that they followed the protocols of their institution regarding patient data disclosure, ensuring confidentiality in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Right to privacy and informed consent The authors obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in this paper. The document is kept by the corresponding author.

text in

text in