1. Introduction

Mangrove forests cover around 13,200,000 ha along tropical and subtropical coasts, with 3,799.54 km2 distributed along the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea coasts of Colombia. These are a highly productive ecosystem with a wide range of species, an essential source of food, tourism, medicinal plants, and forestry products (Hamilton and Casey 2016, Villate et al. 2020). The ecosystem is made up of plants with aerial roots that enhance gas exchange, nutrient recycling, and water purification Stabilize plants on unstable substrates protect against erosion and extreme events like cyclones and tsunamis, and act as litter traps (Chong 2005, Díaz 2011, Kauffman et al. 2011, Ivar do Sul et al. 2014, Norris et al. 2017, Martín et al. 2019).

The mangrove is a fragile ecosystem, affected by disorganized infrastructure planning, industrial development, uncontrolled tourism, deforestation, fishing activities, sedimentation, climate change, and poor litter management (Hartley et al. 2015, Rangel-Buitrago et al. 2017). Deforestation resulted in the loss of 35.0 % of the world´s mangroves in the span between 1980 and 2000 (Valiela et al. 2001, Giesen et al. 2007, Kauffman et al. 2011) with a range of annual deforestation from 2000 to 2012 of 0.16-0.39 % (Fries et al. 2019), and constant litter input is turning the ecosystem into one of the final disposal destinations, contributing to its degradation and converting it into a litter dump (Cordeiro and Costa 2010, Garcés-Ordóñez and Bayona 2019, Riascos et al. 2019).

Marine litter (ML) is defined as any solid and persistent materials manufactured or processed that are disposed of or abandoned in the marine and coastal environment (UNEP 2009). They are indirectly transported by seas, rivers, sewage water, stormwater, winds, and fishing activities, or thrown by people into the sea, beaches, and other marine and coastal ecosystems, like the mangroves (Derraik 2002, Gall and Thompson 2015, Rangel-Buitrago et al. 2019a, Williams and Rangel-Buitrago et al. 2019).

ML (Marine litter) pollution suffocates seedlings by hindering light penetration in the water column, introduces invasive species, induces morbidity of marine species, affects human health (inflammatory lesions, neurodegenerative diseases, immunological disorders, and cancers), and increases negative economic impacts (Boix-Morán 2012, Bulow and Ferdinand 2013, Green et al. 2015, Lozoya et al. 2016, Antão-Barboza et al. 2018, Botterell et al. 2019, Garcés-Ordóñez and Bayona 2019).

Colombia produces about 11.6 million tons of litter annually, of which only 17% is recycled (DANE 2018). A few studies have evaluated the presence and impacts of ML on coastal ecosystems and mangrove forests. In Colombia, ~65.0 % of its coastal populations dispose of their litter in the open air by burning it, burying it in the ground, or dumping it in bodies of water like rivers and lagoons (Gárces-Ordóñez et al. 2019). These studies include the mangroves of the Buenaventura Bay on the Pacific coast (Riascos et al. 2019) and of the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta on the Caribbean coast (Garcés-Ordóñez et al. 2019, Garcés-Ordóñez and Bayona 2019).

Preliminary studies carried out by Williams et al. (2016a), Gracia et al. (2018), and Rangel-Buitrago et al. (2017, 2018, 2019a, 2020) refer to the presence, composition, magnitude, fate, and serious environmental problems related to ML along the Colombian Caribbean coast where the Ciénaga de Mallorquín (CM) is located. The CM is part of a Ramsar site declared in 1998 by Decree 0224, updated in 2009 by Decree 3888. This Ramsar site has a high diversity of fish, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, mollusks, crustaceans, and birds (migratory and endemic).

Recently, relevant restoration projects have been carried out in the CM by the current administration of the District of Barranquilla and by an environmental government agency called EPA Barranquilla Verde (Blanchar et al. 2020). The ecosystem presents environmental degradation caused by increased sedimentation processes, urbanization of nearby areas, illegal deforestation, industrial litter, domestic sewage water, hospital litter, and litter in general (Vera and De La Rosa Muñoz 2003, GTA 2005, Berrocal et al. 2018, Fuentes et al. 2018, Chacón et al. 2020, Portz et al. 2020).

Our study focused on assessing the magnitude, composition, sources, and environmental impacts of ML in the mangrove ecosystem of the CM. As a critical input not only for the recovery and conservation processes of the ecosystem but also to demonstrate the pressing need for formal actions leading to Integrated Coastal Marine Management. It is the first study on this topic in the CM.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study site

The CM is a shallow estuarine coastal lagoon with an area of close to 650 ha and an average depth of 0.90 m, surrounded by floodplains and dunes (Rebolledo-Colina and León-Luna, 2017; Fuentes et al., 2018; Villate et al., 2020). It is located on the Caribbean coast before the mouth of the Magdalena River (75°52’00’’ W and 11°05’00’’ N). This ecosystem is in the jurisdiction of the municipalities of Barranquilla City and Puerto Colombia town (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Location of the CM and surveyed sites inside the mangrove forest with a 9 m2 quadrant in each of the sample points.

The CM is part of the 225,000-ha northern floodplain of the Magdalena River. It communicates with the Caribbean Sea sporadically by natural and human-made events, with one or more openings in the sand bar (Fig. 1). Salinity ranges between 9 and 22 PSU in surface waters and between 14 and 50 PSU in interstitial waters (Chacón et al., 2020; Villate et al., 2020). The CM receives water contributions mainly from hydrographic basins such as Arroyo León and Arroyo Grande-intermittent channels that only provide large volumes of water during the rainy season. The main channel is Arroyo León, with a length of 37 km and a hydrographic area of 247 km2 (Vera and De La Rosa Muñoz, 2003; GTA, 2005; Fuentes et al., 2018).

The CM has three types of vegetation: 1) herbaceous vegetation such as bushes and paddocks; 2) mangroves (Rhizophora mangle L., Avicennia germinans (L.) Stearn, Laguncularia racemosa (L.) C. F. Gaertn. and eventually Conocarpus erectus) and 3) scrub (Vera and De La Rosa Muñoz, 2003).

Mangrove forests make the main structure covering the CM ecosystem, with mainly mixed formations of the basin physiographic type, developed in areas with slow water exchange and high sedimentation rates. There are also monospecific and mixed formations made of three or four species, dominated by A. germinans.

The study was conducted at four sites: (1) Puerto Mocho site (PtM) is a forest made up of two mangrove species (1660 trees ha-1, 20.2 m2*ha-1), dominated by R. mangle. (2) Box Coulvert site (BCv) is a mixed mangrove forest composed of A. germinans, L. racemosa and R. mangle (1360 trees ha-1, 23.6 m2*ha-1). (3) Vía Prosperidad site (VPd) is a narrow strip of mixed mangrove forest composed of L. racemosa, R. mangle, and A. germinans, with good structural development, high conservation status, and excellent phytosanitary conditions. (4) Arroyo León site (ArL) is a mixed forest (2016.7 trees ha-1, 15.8 m2*ha-1) composed of L. racemosa, R. mangle, and A. germinans. ArL is the site with the highest density and the lowest total basal area, suggesting a lower degree of development or a greater degree of degradation.

Despite the degradation of the mangrove forest, the ecosystem has a high diversity of species such as snails, oysters, clams, shrimp, and crabs; and fish species like mullet, tarpon, snook, mojarra, anchovies, bonefish, catfish, and others of great commercial and environmental importance. Bird species are still abundant, mainly pelicans, seagulls, and flamingos (Padilla-Barrios and Pineda-Vides, 2019).

2.2. Litter collection and quantification

The ML-associated pollution in the mangrove forest of the CM was executed by adapting methodologies and international guidelines for monitoring marine litter developed by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP, 2009) and the OSPAR Commission (2010). ML was collected in an area of 9 m2 located close to the body of water in each of the sample points (Fig. 1). The litter density and weight were calculated in terms of the number of items*m-2 and kg*m-2, respectively.

ML types were divided and counted in situ. The OSPAR Commission (2010) proposed a guide used for classifying the ML based on properties, origin, and uses. A total of 135 categories were identified and then grouped into general categories such as plastic, polystyrene, rubber, paper/cardboard, textile, processed wood, glass, metal, medical disposals, fishing gear, organic matter (e.g., pet excrement), cigarette butts, mixed (footwear made of different materials such sandals), and other (unidentified materials).

2.3. ML sources

The quantified ML was classified according to its buoyancy, following the method proposed by Rech et al. (2014) into:

Persistent buoyancy objects: litter items that can potentially float without sinking or decomposing (e.g., plastic, polystyrene, and processed wood).

Intermediate buoyancy objects: short-term litter items transported by currents that sink or decompose in a relatively short time (e.g., rubber, textiles, paper/cardboard, fishing gear, mixed, and organic matter).

Non-floating objects: dense or heavy litter items transported for short distances from the source (e.g., metal and glass).

The Ocean Conservancy proposed a method (2010) to relate the ML items to their sources (economic sector or human activity). The categories of possible sources of marine litter are: 1) shoreline and recreational activities; 2) marine and river activities; 3) smoking-related activities; 4) dumping activities, and 5) disposal of personal care and hygiene items.

2.4. Environmental impact of ML

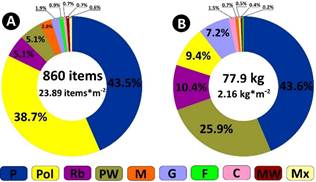

The environmental impact of ML in the mangrove forest of the CM was assessed employing two indexes: The Clean-Coast Index (CCI) modified in this study going from using the total number of articles to their density (not overestimating the results due to the small sample area used on each point), and the Hazardous Items Index (HII). The modified CCI was calculated by quantifying the ML in each mangrove forest study site, based on the index proposed by Alkalay et al. (2007), using the following equation:

where CCI determines the state of cleanliness (absence of ML) and the habits required to achieve and maintain that state (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019a, 2019b), estimated by total items quantified, divided by the total sampling area (m2) and multiplied by the K coefficient equal to 20. Based on the scale provided by Alkalay et al. (2007), resulting values are grouped into five different classes, ranging from I ‘very clean’ to V ‘extremely dirty’.

The HII proposed by Rangel-Buitrago et al. (2019b), measures the possibility of being affected by hazardous marine litter (HML) items that can generate a potential danger (direct or indirect) for any living organism. These are grouped into sharp litter (e.g., metal, glass, and ceramics) and toxic litter (e.g., medications, health, and sanitary paraphernalia). The amount of potentially hazardous litter items (both sharp and toxic) is calculated using the following equation:

HII evaluates the relationship between hazardous litter items and Log10 of the total number of litter items found in the sampled area. K is a coefficient equal to 8, used to generate a better interpretation of the data. In terms of exposure to hazardous litter, the environmental quality of the ecosystem is classified into five classes that range from I ‘Safe site - no hazardous items’ to V ‘Extremely hazardous site - too many hazardous items.

2.5. CCI vs HII in the CM

Following the method proposed by Rangel-Buitrago et al. (2019a), the CCI and the HII were integrated through a sector analysis developed by Williams et al. (2016a, 2016b). A table was constructed using the percentile technique (Langford, 2006) and was divided into three areas:

The green area shows from very clean and clean areas without hazardous items, where protection measures are necessary to maintain current conditions.

The orange area represents moderate cleanliness sites with a considerable number of hazardous items and where cleaning actions are necessary.

The red area describes from dirty to extremely dirty areas with a large number of hazardous items where urgent intervention and even restoration measures are necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Marine litter characterization

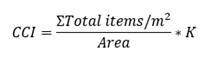

A total of 860 items were collected in the 36 m2 area of mangrove forest in the CM; these items weighed 77.9 kg of ML and had an average item density of 23.89 items*m-2, and an average weight density of 2.16 kg*m-2 (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1 Categories, types, sources, items number, densities (items*m-2), and percentages of marine litter observed at each site inside the mangrove forest of the Ciénaga de Mallorquín. Sites: Puerto Mocho (PtM), Box Coulvert (BCv), Vía Prosperidad (VPd), and Arroyo León (ArL). Plastic [P], polystyrene [Pol], rubber [Rb], processed wood [PW], metal [M], glass [G], fishing gear [F], cloth [C], medical disposals [MW], and mixed items [Mx].

| Ospar Code | Item | Type | Source | PtM | BCv | VPd | ArL | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | Density | Nº | Density | Nº | Density | Nº | Density | Nº | Density | % | ||||

| 2 | Bags | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 26 | 2.89 | 0 | 0.00 | 26 | 0.72 | 3.02 |

| 3 | Small plastic bags | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.11 | 0.47 |

| 4 | Drinks (bottles, containers, and drums) | [P] | Shoreline and Recreational | 3 | 0.33 | 4 | 0.44 | 16 | 1.78 | 82 | 9.11 | 105 | 2.92 | 12.21 |

| 5 | Cleaner (bottles, containers, and drums) | [P] | Dumping | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 2 | 0.22 | 3 | 0.33 | 8 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| 6 | Food containers ind. Fast food containers | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 5 | 0.56 | 2 | 0.22 | 8 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| 7 | Cosmetics | [P] | Medical/Personal Hygiene | 1 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.44 | 2 | 0.22 | 12 | 1.33 | 19 | 0.53 | 2.21 |

| * | Cooking oil containers | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.44 | 10 | 1.11 | 16 | 1.78 | 30 | 0.83 | 3.49 |

| 8 | Engine oil containers and drums <50 cm | [P] | Ocean/waterway | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.58 |

| 12 | Other bottles, containers and drums | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.22 | 4 | 0.44 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.17 | 0.70 |

| 14 | Car parts / Electric applicances | [P] | Dumping | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.56 | 2 | 0.22 | 8 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| 15 | Caps / lids | [P] | Shoreline and Recreational | 3 | 0.33 | 13 | 1.44 | 26 | 2.89 | 69 | 7.67 | 111 | 3.08 | 12.91 |

| 16 | Cigarrete lighters | [P] | Smoking-Related | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.22 | 4 | 0.44 | 6 | 0.17 | 0.70 |

| 17 | Pens | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.35 |

| 18 | Combs / hairbrushes | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.44 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.58 |

| * | Tootbrush | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.35 |

| * | Kitchen utensils | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| 20 | Toys and party poppers | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.33 | 6 | 0.67 | 9 | 0.25 | 1.05 |

| 21 | Cups | [P] | Shoreline and Recreational | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.33 | 5 | 0.56 | 10 | 0.28 | 1.16 |

| 22 | Cutlery / trays / straws | [P] | Shoreline and Recreational | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.44 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.58 |

| 23 | Mesh vegetable bags | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 48 | Other plastic items | [P] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 19 | 2.11 | 19 | 0.53 | 2.21 |

| 6 | Food containers ind. Fast food containers | [Pol] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 7 | 0.78 | 5 | 0.56 | 13 | 0.36 | 1.51 |

| 45 | Foam sponge | [Pol] | Ocean/waterway | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 0.89 | 18 | 2.00 | 26 | 0.72 | 3.02 |

| 117 | Polystyrene pieces 0 - 2,5 cm | [Pol] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 1.78 | 46 | 5.11 | 62 | 1.72 | 7.21 |

| 46 | Polystyrene pieces 2,5 - 50 cm | [Pol] | Dumping | 1 | 0.11 | 15 | 1.67 | 61 | 6.78 | 110 | 12.22 | 187 | 5.19 | 21.74 |

| 47 | Polystyrene pieces >50 cm | [Pol] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 1.78 | 10 | 1.11 | 26 | 0.72 | 3.02 |

| 49 | Ballons, valves, ribbons, strings, etc. | [Rb] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 50 | Boots/Shoes/sandals | [Rb] | Shoreline and Recreational | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.44 | 34 | 3.78 | 39 | 1.08 | 4.53 |

| 52 | Tires and belts | [Rb] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| 53 | Other rubber pieces | [Rb] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| 57 | Shoes (e.g., leather) | [C] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.44 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.58 |

| 59 | Other textiles | [C] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| 74 | Other woods <50 cm | [PW] | Dumping | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 4 | 0.44 | 4 | 0.44 | 11 | 0.31 | 1.28 |

| 75 | Other woods >50 cm | [PW] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 13 | 1.44 | 20 | 2.22 | 33 | 0.92 | 3.84 |

| 77 | Bottle caps | [M]** | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.22 | 6 | 0.67 | 8 | 0.22 | 0.93 |

| 89 | Other metal pieces | [M]** | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 13 | 1.44 | 3 | 0.33 | 16 | 0.44 | 1.86 |

| 91 | Bottles | [G]** | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.33 | 8 | 0.89 | 12 | 0.33 | 1.40 |

| 92 | Light bulbs / tubes | [G]** | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| * | Cosmetic containers (e.g., perfumes) | [G]** | Medical/Personal Hygiene | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.35 |

| 103 | Medicine containers | [MW]** | Medical/Personal Hygiene | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 1 | 0.11 | 2 | 0.22 | 6 | 0.17 | 0.70 |

| 115 | Nets and pieces of net < 50 cm | [F] | Ocean/waterway | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| 33 | Fragments fishing nets | [F] | Ocean/waterway | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.11 | 7 | 0.19 | 0.81 |

| * | Footwear | [Mx] | Dumping | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.11 | 4 | 0.44 | 5 | 0.14 | 0.58 |

| Total | 15 | 1.67 | 56 | 6.22 | 275 | 30.56 | 514 | 57.11 | 860 | 23.89 | 100.00 | |||

| HML | 2 | 0.22 | 3 | 0.33 | 21 | 2.33 | 20 | 2.22 | 46 | 1.28 | 5.35 | |||

| CCI | 3.71 | - | 13.82 | - | 67.91 | - | 126.91 | - | 13.27 | - | - | |||

| HII | 1.51 | - | 1.52 | - | 7.65 | - | 6.56 | - | 3.48 | - | - | |||

* Litter items not described by Ocean Conservancy (2010).

** HML collected in this study.

Figure 2 Magnitude and composition of marine litter: (A) number of items and (B) weight (kg). Plastic [P], polystyrene [Pol], rubber [Rb], processed wood [PW], metal [M], glass [G], fishing gear [F], cloth [C], medical disposals [MW], and mixed items [Mx].

The densities of ML varied depending on the sampled sites. The Arroyo León site (ArL) registered the highest density, with 57.11 items*m-2 and 60.0 % of the total ML collected in the CM, followed by the Via Prosperidad site (VPd), with a density of 30.56 items*m-2 and 32.0 % of the total ML collected (Table 1). Together, Puerto Mocho (PtM) and Box Coulvert (BCv) represented 8.0 % of the total ML recorded in our study, with densities of 1.67 items*m-2 and 6.22 items*m-2, respectively (Table 1).

Still, plastic and polystyrene were the most abundant litter items registered, each one representing 43.5 % (10.38 items*m-2) and 38.7 % (9.25 items*m-2) of all ML collected. Which was true in each site sampled, where the plastic composition was between 41.5 % and 66.7 %, and that of polystyrene was between 28.6 % and 40.5 %. Other items found were rubber (5.1%), processed wood (5.1 %), metal (2.8 %), and glass (1.9 %). Textiles, medical disposals, fishing gear, and mixed items such as sandals made up only 0.9 % to 0.6 % of the items collected (Table 1, Fig. 2a).

In terms of weight, plastic (43.6 %, 0.94 kg*m-2) and processed wood (25.9 %, 0.56 kg*m-2) were the predominant items in the litter collected due to their large volume and higher density. Next was rubber (0.23 kg*m-2), polystyrene (0.20 kg*m-2), and glass (0.16 kg*m-2) (Fig. 2b). This result, both in terms of number of items and weight, highlights the fact that plastics were the main ML items collected in the mangrove forest of the CM, with a total of 374 items and 34 kg (Table 1, Fig. 2).

3.2. Buoyancy and sources of ML

The 87.3% of items collected in the study area were of persistent buoyancy, followed by intermediate buoyancy (8.0 %) and non-buoyancy (4.7 %). Similar results were registered in the remaining sample sites, with ML of persistent buoyancy between 80.0 % and 94.6 % (Table 2).

Table 2 Buoyancy (%) of ML at each site and along the study area surveyed in the Ciénaga de Mallorquín. Sites: Puerto Mocho (PtM), Box Coulvert (BCv), Vía Prosperidad (VPd), and Arroyo León (ArL).

| Buoyancy | PtM | BCv | VPd | ArL | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Persistent | 80.0 | 94.6 | 86.9 | 87.0 | 87.3 |

| Intermediate | 13.3 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 9.5 | 8.0 |

| No buoyancy | 6.7 | 1.8 | 7.3 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

Based on the Ocean Conservancy method (2010), 43 categories of litter were identified, consisting of plastic items (21), polystyrene (5) (Fig. 3a, d), rubber (4) (Fig. 3c), glass (3) (Fig. 3f), processed wood (2), metal (2), fishing gear (2) (Fig. E), textile (2), medical disposals (1) (Fig. 3b) and varied items (1). Most items collected come from dumping activities at 59.2 % (14.14 items*m-2) (e.g., cooking oil containers and toys), followed by the shoreline and recreational activities with 31.4 % (7.50 items*m-2) (e.g., soda containers, caps/lids, and footwear), ocean/waterway with 4.5 % (e.g., fishing gear leftovers), personal care and hygiene with 4.2 % (e.g., cosmetic and medicine containers) and smoking-related with 0.7 % (cigarette lighters) (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Different kinds of ML were collected in the mangrove forest of the Ciénaga de Mallorquín. Items: plastic (A), glass containers (B), rubber footwear (C), food packaging (D), remains of fishing gear (E), and medicine containers (F).

Table 3 The number of items, percentages, and average density (items*m-2) of ML in the mangrove forest of the Ciénaga de Mallorquín concerning sources and activities. Sites: Puerto Mocho (PtM), Box Coulvert (BCv), Vía Prosperidad (VPd), and Arroyo León (ArL).

| Source/Activity | PtM | BCv | VPd | ArL | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nº | % | Nº | % | Nº | % | Nº | % | Nº | Avg. Density | % | |

| Shoreline and Recreational (1) | 8 | 53.33 | 18 | 32.14 | 50 | 18.18 | 194 | 37.74 | 270 | 7.50 | 31.40 |

| Ocean/waterway (2) | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 5.36 | 16 | 5.82 | 20 | 3.89 | 39 | 1.08 | 4.53 |

| Smoking-Related (3) | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.73 | 4 | 0.78 | 6 | 0.17 | 0.70 |

| Dumping (4) | 4 | 26.67 | 28 | 50.00 | 201 | 73.09 | 276 | 53.70 | 509 | 14.14 | 59.19 |

| personal care and hygiene (5) | 3 | 20.00 | 7 | 12.50 | 6 | 2.18 | 20 | 3.89 | 36 | 1.00 | 4.19 |

| Total | 15 | 100 | 56 | 100 | 275 | 100 | 514 | 100 | 860 | 23,89 | 100 |

Mainly littering by beach tourists, but also from waterside sports or debris washed away from streets, drains, and gutters.

Solid waste from recreational fishing/boating, recreational/commercial fishing, recreational/commercial shipping, and the oil and gas industry.

In Colombia, cigarette lighters are commonly used for cooking activities.

ML is derived from building and construction materials, tires, car parts, drums, household trash, and appliances.

Materials discarded into toilets/sewer system or left behind by beach tourists.

The BCv, VPd, and ArL sites had mainly litter from dumping activities, given their proximity to the mouth of tributaries of the Arroyo León hydrographic basin and the Magdalena River basin (Fig. 4a, b) and also their proximity to open-air Sanitary landfills.

Figure 4 Evidence of marine litter from the estuaries of a) the Arroyo León Stream near site ArL, b) the Magdalena River near site BCv, and c) litter dumps near the mangrove forest.

The PtM site located northeast of the CM and far from stream mouths-registered a higher composition of litter accumulated at the shoreline and from recreational activities (Table 3). The PtM site is located also, near a residential area on the Puerto Mocho beach with a population that occasionally dumps its trash outdoors on the margins of the mangrove lagoon (Fig. 4c, d).

3.3. CCI vs HII in the CM

The CM with 860 articles of marine litter obtained a dirty state with a value of 13.27 based on the CCI (Class IV). In turn, the CM presented a considerable quantity of HML with a value of 3.48 based on the HII (Class III) for the 46 hazardous litter items that were found (5.3 % of the total collected throughout the study area) and classified as either sharp (glass and metal) or toxic (medicine containers) (Table 1, Fig. 2a). The CM obtained this status due to the entry and accumulation of ML in three of the four evaluated sites, with the VPd and ArL classified as extremely dirty based in the CCI (Class V, with densities of 30.56 items*m-2 and 57.11 items*m-2) and was a lot HML based in the HII (Class IV, with densities of 2.33 items*m-2 and 2.22 items*m-2), respectively. The BCv site was classified as dirty based in the CCI (Class IV, with a density of 6.22 items*m-2) and had a considerable amount of HML based in the HII (Class III, with a density of 0.33 items*m-2). The PtM was the only site considered clean based in the CCI (Class I, with a density of 1.67 items*m-2) and presented a considerable amount of HML based in the HII (Class III, with a density of 0.22 items*m-2) (Table 1, Fig. 5).

Figure 5 Sector Analysis Approach. Integration of the Clean Coast Index (CCI) with the Hazardous Items Index (HII).

This type of litter consisted of sharp objects, such as metal and glass (40 items, see Fig. 3f), or toxic items like medicine containers (6 items, see Fig. 3b), that come from dumping activities (37 items), personal care and hygiene debris (9 items) (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The 23.89 items*m-2 in the CM represent a large amount of litter from different sources and litter-generating activities and make it one of the mangrove ecosystems with the highest density of ML among different studies published around the world. Similar results were recorded by Smith (2012) in Papua New Guinea, Australia (15.29 items*m-2); Fernandino et al. (2016) in the Estuarine System of Santos - São Vicente, Brazil (7.80 items*m-2); Riascos et al. (2019) in the Buenaventura Bay, Colombia (13.25 items*m-2); and Chee et al. (2020) in the Mangroves on Penang Island, Malaysia (8.15 items*m-2) all representing high values of ML density (Table 4).

Table 4 Density (items*m-2) of ML and HML, and composition (%) of plastic (P) in mangrove forests around the world.

| Country | Specific zone | Sites | Total area (m2) | Average density | Avera ge density HML | [P] (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | São Paulo Vicente | 8 | 1,600 | 1.33 | 0.14 | 0.62 | Cordeiro y Costa 2010 |

| United States | Sal marshes of northern California | 15 | 63,096 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.40 | Viehman et al. 2011 |

| Papua New Guinea | Bootles Bay | 20 | 219 | 15.29 | 0.52 | 0.90 | Smith 2012 |

| Brazil | Paranaguá Estuarine Complex, Paraná state | 6 | 124,518 | 0.0023 | 0.0003 | 0.84 | Possatto et al. 2015 |

| Brazil | Estuarine system of Santos - São Vicente | 6 | 300 | 7.80 | 0.07 | 0.90 | Fernandino et al. 2016 |

| Brazil | Paranaguá Estuarine Complex, Paraná state | 6 | 4,500 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.58 | Krelling et al. 2017 |

| Philipines | Mayo Bay | 2 | 2,400 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.95 | Abreo et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (CGSM) | 6 | 44,445 | 0.054 | 0.003 | 0.94 | Garcés-Ordóñez et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Buenaventura Bay | 4 | 154 | 13.25 | 2.81 | 0.65 | Riascos et al. 2019 |

| Saudi Arabia | Red Sea and Arabian Gulf | 20 | 2,263.5 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.82 | Martín et al. 2019 |

| Spain | Pas, Miera and Asón estuaries | 32 | 1,900 | 1.53 | 0.32 | 0.76 | Mazarrasa et al. 2019 |

| Malaysia | Mangroves on Penang Island | 3 | 1,200 | 8.15 | 0.47 | 0.90 | Chee et al. 2020 |

| Brazil | Estuary of the Pará River | 8 | 20,286 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.15 | Gonçalves et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Commune Puerto Roma, Province of Guayas | 4 | 70 | 2.90 | 0.11 | 0.71 | Jacho 2020 |

| Mauritius | Mangrove forests of Mauritius | 2 | 1,500 | 1,42 | - | 0,43 | Seeruttun et al. 2021 |

| Colombia | Ciénaga de Mallorquín | 4 | 36 | 23.89 | 1.28 | 0.82 | This study |

The density of 1.28 items*m-2 of HML registered in this study is higher than the reported in other studies of sites with large volumes of ML with a considerable amount of sharp and toxic litter items. For example, Cordeiro and Costa (2010) registered a density of 0.14 items*m-2, Fernandino et al. (2016) 0.07 items*m-2, Krelling et al. (2017) 0.03 items*m-2, Martin et al. (2019) 0.08 items*m-2, Mazarrasa et al. (2019) 0.32 items*m-2, Chee et al. (2020) 0.47 items*m-2, and Gonçalves et al. (2020) 0.18 items*m-2. Currently, the highest density of HML for mangroves was registered by Riascos et al. (2019) in Buenaventura Bay, Colombia, with a density of 2.81 items*m-2 (Table 4).

The average ML density in weight in the mangrove forest stands of the CM was 2.16 kg*m-2, confirming that this is an ecosystem with a high input of litter. For example, on the 28th of October, 2017, the Secretariat of the District of Urban Control and Public Space of Barranquilla, the environmental authority ‘Barranquilla Verde’, and volunteers from the civil society and fishermen´s associations collected 5 tons of solid litter in 2200 m2 of mangrove inside the CM; these 5 tons represent an average density in weight of 2.27 kg*m-2. At the same time, on the 6th of February, 2021, as part of a Neotropical Census of Waterbirds; and clean-up activities carried out in the CM, 84 kg of recyclable and 62 kg of non-recyclable litter were collected. These values exceed by up to an order of magnitude those registered by Cordeiro and Costa (2010) in the São Vicente Estuary, Brazil (0.13 kg*m-2) and Riascos et al. (2019) in the Buenaventura Bay, Colombia (0.002 - 0.31 kg*m-2), becoming the ecosystems with the highest values of ML by weight per square meter of mangrove.

Plastic and polystyrene (another kind of plastic, but separated in the typology due to its high magnitude in the study area), with densities of 10.39 items*m-2 and 9.25 items*m-2, respectively, are the common denominator in ML in the mangrove forest of the CM (82.2 %) (Table 1, Fig. 3a), a condition common to the Colombian Caribbean coast (Williams et al. 2016a, 2016b, Botero et al. 2020, Garcia et al. 2018, Rangel-Buitrago et al. 2017, 2018, 2019a, 2020, Garcés-Ordóñez et al. 2020), the mangroves in the Colombian Caribbean coast (Garcés-Ordóñez et al., 2019) and the Colombian Pacific coast (Riascos et al., 2019), as well as all mangrove ecosystems around the world (Cordeiro and Costa, 2010; Fernandino et al., 2016; Krelling et al., 2017; Martín et al., 2019; Mazarrasa et al., 2019; Suyadi and Manullang, 2020) (Table 4).

ML pollution of the mangrove forest stands of the CM is aggravated by the large population of the District of Barranquilla (1,239,804 inhabitants), with the highest national litter production levels: about 1.20 kg of litter per person per day, compared to the overall national average 0.90 kg (SSPD, 2017; DANE, 2020). Between 2016 and 2018, Barranquilla generated an average of 46,519.9 tons of litter per month, of which only 2.05 % (954.3 tons) was recycled (SSPD, 2019). Inadequate handling of its solid debris is evident, with part of the litter deliberately thrown into local streams in Barranquilla (Rebolledo-Colina and León-Luna, 2017; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2020). Despite all the legal framework and all the institutions in charge of issuing the guidelines to regulate litter management (CCO, 2018), Colombia is a country where 11.0 % of its municipalities and cities use open-air dumps to dispose of their litter or dump it directly in the nearest bodies of water (Vivas-Aguas et al., 2015).

Our results confirm other studies carried out in mangrove forests in Colombia. Garcés-Ordóñez et al. (2019) and Riascos et al. (2019) conclude that solid litter is by far poorly managed, with approximately 65.0 % of coastal municipalities inadequately disposing of their litter causing it to accumulate in mangroves near urban areas. This problem is leading the mangrove forest of the CM to become a litter dump.

The large volumes of ML registered are due to several causes, including the high buoyancy of the litter (Rech et al., 2014, 2018) as observed in this study (Table 2); its resistance and durability (Derraik, 2002; Hardesty et al., 2016; Buhl-Mortensen and Buhl-Mortensen, 2017), the large amount of litter transported from hydrographic basins (Cordeiro and Costa, 2010; Riascos et al., 2019), and the potential of mangroves to retain and accumulate litter (Ivar do Sul et al., 2014; Smith and Edgar, 2014; Martín et al. 2019).

Most litter accumulated in the CM comes mainly from continental sources and is transported by the Magdalena River and multiple streams in the basin or deliberately dumped near the ecosystem (Table 3). Similar patterns were found in mangrove areas of Guatemala (Boix-Morán, 2012), on the Colombian Caribbean coast (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2017, 2020), and in different studies around the world (Cheshire et al., 2009; Ivar do Sul and Costa, 2013; Galgani et al., 2015; Jambeck et al., 2015) where 80 to 90% of ML comes from continental sources, and less than 10% from open sea activities. In the mangrove forest of the CM, dumping activity was determined as the primary source of ML in the ecosystem.

The Arroyo León Basin (where the ArL site is located) and the Arroyo Grande Basin together host the municipalities of Puerto Colombia, Galapa, Baranoa, Tubará, and part of the urban area of the Barranquilla District, totaling a population of 1,386,688 - 53.3 % of the total population of the department (DANE, 2020) and contributing with much of the litter accumulated in the CM. On the other hand, the VPd site piles up ML that comes from the neighborhoods of Las Flores and La Playa, with 78,000 inhabitants (Corredor, 2018). For many years, Las Flores had a sanitary landfill that flowed directly into the water body of the CM (GTA, 2005), and La Playa lacks an environmental sanitation plan (Rebolledo-Colina and León-Luna, 2017; Berrocal et al., 2018).

The Magdalena River also carries a large volume of ML to the mangrove forest in the CM. The BCv site, with a moderate density of litter, receives its input from litter transported by the Magdalena River (50.0 %) from dumping activities and from the shoreline and recreational activities (32.1 %) (Table 3). The Magdalena River is the prime hydrographic basin in the country, crossing 724 municipalities; unfortunately, 46.0 % of these municipalities do not have an appropriate litter disposal system (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2017).

Another source of ML in this ecosystem is debris deliberately thrown near the mangrove forest by residents of Puerto Mocho Beach (Fig. 4c). This situation is of concern because, during natural flooding events, this solid litter is carried into the mangrove forest and retained by the aerial roots of the mangrove species (Cordeiro and Costa, 2010; Garcés-Ordóñez and Arenas, 2019; Martín et al., 2019), together with the potential retainer of the plastic of the other typologies of ML (Vélez-Mendoza, 2022).

The high population density in the city of Barranquilla has led to human settlements in mangrove areas (Las Flores and La Playa). The large volumes of ML input from different sources and the inadequate management of natural resources and solid litter have led to ecosystem degradation. The mangrove forest of the CM was classified as having a dirty state, with a value close to those of other coastal sites, like the beaches of the Department of Atlántico and Isla Arena in Bolivar, where most locations were classified as dirty or extremely dirty (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019a, 2020).

The high density of ML in mangrove stands has collateral effects on the ecosystem and its biota and is also a potential risk for the health and physical integrity of inhabitants and visitors (Somerville et al., 2003; Garcés-Ordóñez and Bayona, 2019; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2019a, 2019b). Initiatives led by government entities, fishermen´s associations, and volunteers to remove litter and plant mangroves in the CM may potentially expose participants to the risk of sharp and toxic litter items such as metal, glass, and medicine containers.

These results joined with those obtained by the sector analysis (Fig. 5), show that large amounts of ML increase the possibility of finding HML harmful to the ecosystem, biota, health, and human physical integrity, highlighting the need for urgent intervention and restoration measures at the VPd and ArL sites. For this reason, visiting these areas is not recommended unless minimum measures of personal care are taken (e.g., use of boots, jeans, and gloves). The PtM and BCv sites receive less ML that still needs adequate management and cleaning actions. Regardless of the condition and status of each site sampled, the mangrove forest of the CM needs the cooperation of all possible actors involved actors: citizens, public and government entities, private sector, and international agreements, together with efficient, comprehensive, and proactive strategies for controlling and reducing dumping, recycling or reusing waste, and eliminating ML sources.

The Development Bank of Latin America (Corporación Andina de Fomento, CAF) is currently designing, formulating, and financing an ambitious recovery project for the CM "focused on the environmental management of the Ciénaga de Mallorquín, to promote low-carbon and climate-resilient development." The project includes an entire urban development articulated with the natural landscape through "stilt structures above the ecosystem, with fishing docks, and areas for recreational activities and water sports, and especially a space for interaction with nature." However, the project does not mention a plan for integral management of the ecosystem.

Our results demonstrate the urgent need to design and implement actions aimed at the integral recovery of the ecosystem. Therefore, the previous project may be the best opportunity to formulate and develop an Integrated Coastal Marine Management plan, where different sectors like the economic, productive, environmental, social, authorities, environmental and territorial entities, and local communities could participate in the recovery and protect this essential ecosystem, referred to as ‘Barranquilla’s lung’ and turn it into ‘Barranquilla’s biodiversity’ showcase.

5. Conclusions

Despite the various and recurring cleanup activities carried out in recent years in the CM mangrove, this ecosystem continues to suffer from a high input of ML. Among the primary sources are the litter discharge activities from the urban area and transported to the ecosystem by hydrographic basins (eg, ArL site), and that caused by the defective or non-existent management of litter generated in recreational and shoreline activities in urban centers located near to the ecosystem (eg, VPd site).

The high average density of ML in the CM confirms that its mangrove forest presents a high influx of ML, causing three of the four sites evaluated to require urgent restoration measures, mainly due to the dominance of plastic items. Plastic, due to its persistent buoyancy and ability to retain other types of litter along with the mangrove roots is negatively influencing the cleanliness and safety of the ecosystem, its biota, and the health and physical integrity of the people (eg, residents of the area who depend on the natural resources provided by the ecosystem) due to the presence and accumulation of HML.