Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Biomédica

Print version ISSN 0120-4157

Biomédica vol.32 no.3 Bogotá Jul./Sept. 2012

https://doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v32i3.707

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v32i3.707

1Grupo de Microbiología, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia

2Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas, Medellín, Colombia

3Hospital Universitario Erasmo Meoz, Cúcuta, Colombia

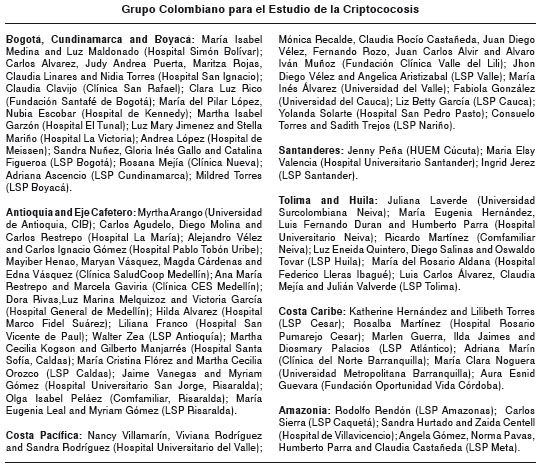

4Grupo Colombiano para el Estudio de la Criptococosis

Author contributions: Patricia Escandón: played an important role in writing and preparing the manuscript, in charge of the surveillance at the Instituto Nacional de Salud, controlled receipt of questionnaires.

Catalina de Bedout: in charge of the mycological diagnosis for all Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas cases, established links with physicians in charge of patients, controlled receipt of questionnaires and performed the susceptibility testing in all isolates.

Jairo Lizarazo: physician in charge of the patients from Norte de Santander, checked the questionnaire’s contents for medical accuracy, analyzed the data through statistical analysis.

Clara Inés Agudelo: worked all long in the surveillance study, played an important role in preparation of the manuscript and in the analysis of the data, including statistical tests.

Ángela Tobón: examined many of the Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas patients, filled in the corresponding questionnaires, supervised the clinical aspects of most patients and served as a consultant for other physicians in charge of cryptococcosis patients.

Solmara Bello: in charge of the mycological diagnosis for Instituto Nacional de Salud cases.

Ángela Restrepo: surveillance of the whole program, contacting physicians and serving as consultant for all participants, analyzing data, writing of the manuscript and analyzing results.

Elizabeth Castañeda: conceived the plan for the surveillance program, orchestrated connections with hospitals, diagnostic centers and worked all along the development of the study, including writing and analyzing the manuscript.

The Colombian Cryptococcosis Study Group: a large group composed by all physicians and clinical personnel filling in the questionnaire when diagnosing a cryptococcosis case.

Recibido:02/12/11; aceptado:19/04/12

Introduction: A survey on cryptococcosis is being conducted regularly in Colombia since 1997. We present hereby the results corresponding to patients diagnosed from 2006 to 2010.

Objective: To analyze the data obtained during this period.

Materials and methods: Retrospective analysis of the corresponding surveys.

Results: A total of 526 surveys originating from 72% of the Colombian political divisions were received during the 5-year period. Most patients (76.6%) were males and 74.9% were 21-50 years old. The most prevalent risk factor was HIV infection (83.5%) with cryptococcosis defining AIDS in 23% of the cases. In the general population the estimated mean annual incidence rate for cryptococcosis was 2.4 x 106 inhabitants while in AIDS patients this rate rose to 3.3 x 103. In 474 surveys stating clinical features, most frequent complaints were headache 84.5%, fever 63.4%, nausea and vomiting 57.5%, mental alterations 46.3%, meningeal signs 33.0%, cough 26.4% and visual alterations 24.5%. Neurocryptococcosis was recorded in 81.8% of the cases. Laboratory diagnosis was based on direct examination, culture and latex in 29.3% cases. From 413 Cryptococcus isolates analyzed, 95.6% were identified as C. neoformans var. grubii, 1% C. neoformans var. neoformans, and 3.4% C. gattii. Treatment was reported for 71.6% of the cases with amphotericin B alone or in combination with fluconazole prescribed in 28%.

Conclusions: Surveys done through passive surveillance continue to be sentinel markers for HIV infection and represent a systematic approach to the study of opportunistic problems regularly afflicting AIDS patients since cryptococcosis requires no compulsory notification in Colombia.

Key words: Cryptococcosis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gattii, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, morbidity, mortality, Colombia

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v32i3.707

Criptococosis en Colombia: resultados de la encuesta nacional, 2006-2010

Introducción. Desde 1997 se viene realizando un programa nacional de vigilancia sobre la criptococosis en Colombia. Se presentan los resultados correspondientes a los pacientes diagnosticados entre el 2006 y el 2010.

Objetivo. Analizar los datos obtenidos durante este periodo.

Materiales y métodos. Análisis retrospectivo de las encuestas.

Resultados. Durante los cinco años mencionados se recibieron 526 encuestas representativas del 72 % de la división política colombiana. La mayoría de pacientes (76,6 %) eran hombres y 74,9 % estaban entre los 21 y los 50 años. El factor de riesgo prevalente fue la infección por VIH (83,5 %), y la criptococosis definió el sida en 23 % de los casos. La incidencia anual promedio en la población general fue de 2,4 por un millón de habitantes mientras que, en pacientes con sida, aumentó a 3,3 por 1.000. En 474 encuestas se informaron manifestaciones clínicas; las más frecuentes fueron: cefalea (84,5 %), fiebre (63,4 %), náuseas y vómito (57,5 %), alteraciones mentales (46,3 %), signos meníngeos (33 %), tos (26,4 %) y alteraciones visuales (24,5 %). La neurocriptococosis se reportó en 81,8 % de los casos. El diagnóstico se hizo por examen directo, cultivo y antigenemia en 29,3 % de los casos. De 413 aislamientos recuperados, 95,6 % fueron C. neoformans var. grubii, 1 % C. neoformans var. neoformans, y 3,4 % C. gattii. En 71,6 % de los casos para el tratamiento se administró anfotericina B y en 28 % se combinó con fluconazol.

Conclusiones. La vigilancia pasiva continúa siendo un marcador centinela para la infección por VIH, y constituye una aproximación sistemática al estudio de infecciones oportunistas en pacientes con sida, debido a que la criptococosis no es de notificación obligatoria en Colombia

Palabras clave: criptococosis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Cryptococcus gattii, síndrome de inmunodeficiencia adquirida, morbilidad, mortalidad, Colombia

[doi]doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.7705/biomedica.v32i3.707[/doi]

Cryptococcosis, an opportunistic mycosis affecting both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients, is acquired by the inhalation of the fungal propagules, small capsulated yeasts and probably also basidiospores, present in the environment (1).

At present, the etiological agent is classified in the Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii species complex, with two species and several hybrids: C. neoformans var. grubii, serotype A, C. neoformans var. neoformans, serotype D, C. gattii, serotypes B and C and the hybrids AD, BD, AA, and AB (2-5).

Although it is known that both species affect primarily the lungs and secondarily the central nervous system (CNS), there are certain differences in the epidemiology and clinical presentation of the diseases. C. neoformans var. grubii is responsible of almost all the infections in AIDS patients whilst C. gattii affects mainly apparently immunocompetent persons (6). Both C. neoformans and C. gattii invade essentially the cerebral parenchyma; however, C. gattii is more likely to produce pulmonary and cerebral masses (cryptococcomas) (6).

Since 1981, as a consequence of the AIDS epidemic and other type of immunosuppression conditions, infections caused by the members of the C. neoformans complex have become important causes of morbid-mortality with approximately 5-10% of the patients with CD4+ lymphopenia developing cryptococcosis (7). At present, this mycosis is classified among the three most important opportunistic infections leading to death in AIDS patients (8). The prevalence of the disease in these patients has diminished thanks to the introduction of the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) but the viral disease is still epidemic in Africa and Southeast Asia, where nearly 30% of the patients with AIDS are affected by cryptococcosis (8,9).

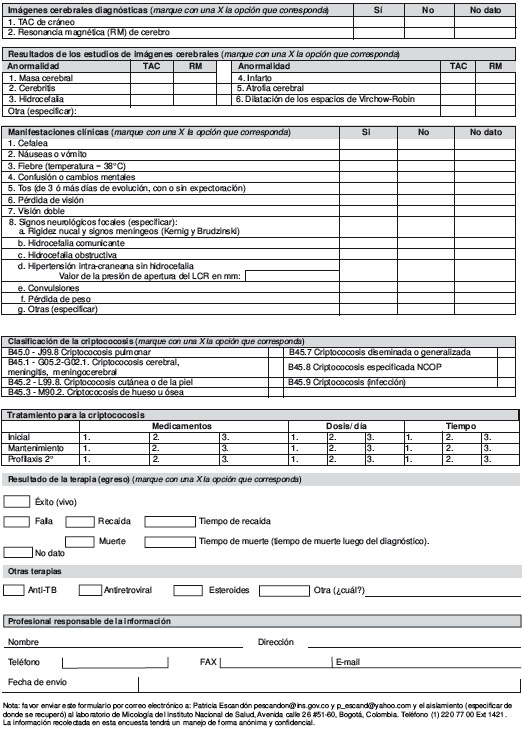

Even though in Colombia cryptococcosis does not require compulsory notification, a series of reports reveal its importance in the country (10-15). In the year 1997, a national survey centered in cryptococcosis was designed with the aim of identifying the demographic characteristics of the afflicted Colombian population, the risk factors involved, the laboratory assays employed for diagnosis, the etiological agents involved, and the initial treatment given to the patients (16). Recently, an update on the survey’s questionnaire was done, in which, additional to the data already mentioned, the person in charge of filling the survey specified what type of cryptococcosis was diagnosed and what were the results of the therapy given to the patients (see supplement 1).

The aim of this work was to analysis the results obtained during the cryptococcosis national survey for the period 2006-2010.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a descriptive observational study in which clinical and epidemiological information on cryptococcosis cases was gathered from the survey done during the period 2006-2010. The survey was designed according to the guidelines established by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology, with the corresponding authorization (17); the formularies were filled out by health professionals in public, private and educational institutions, as well as in public health laboratories across the country.

In the survey, the following entries were considered: patients demographic data, gender and age, year and geographic department of birth, place of residence, risk factors (HIV infection, use of corticosteroids, autoimmune disease, transplants, solid tumor, hematological malignancy, diabetes mellitus, hepatic cirrhosis, renal failure, sarcoidosis). We inquired if cryptococcosis was an AIDS defining illness, we asked about diagnosis date, clinical manifestations of the disease, condition of the patient when leaving the health center and type of clinical treatment. The diagnostic tests employed were also registered taking into consideration fungal visualization and culture test results, determination of the capsular antigen in CSF or sera, and data on the results of the diagnostic images (chest X-ray, cerebral images). Information about other types of treatment received by the patient (anti-TB, antiretroviral) was also requested.

The surveys and isolates were sent to the study coordinating centers (Instituto Nacional de Salud in Bogotá and Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas in Medellín) and a database was created in the Biolomics software and the analysis was done in the statistical program Epiinfo 6.1.

Furthermore, a comparison between the data obtained in this study with the information published for the 1997-2005 period was also done (16).

Ethical considerations

The present study received the approval of the Ethics Committee of the CIB. Its implementation was subjected to the principles stated in the Helsinki declaration concerning medical research in human beings. Due to the descriptive character of the study and considering that the research reported was exempt of any risk to the subjects whose data were employed, an informed consent was not obtained. This was in accordance with Resolution 8430 issued in 1993 by the Ministry of Health of Colombia in charge of regulating medical research in the country. Furthermore all clinical and para-clinical procedures employed were those required by the consulting physician for the establishment of the diagnosis with no extra tests being carried out. The authors did not intervene with the patients and only processed their samples as ordered by the physician in charge.

Case definition

A case was defined when clinical findings compatible with cryptococcosis were noticed, as well as when one or several of the following laboratory results were present: isolation of the fungus from a normally sterile site, or from sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage and/or skin lesions. Additionally, fungal visualization in a CSF direct examination with India ink, or in a cutaneous lesion, or in a biopsy, as well as a capsular antigen titer ≥ 8 in sera or any titer in CSF, were considered diagnostic tests.

Patients with relapsing disease were also included in the survey if the new clinical episode had occurred 6 or more months after the initial diagnosis (16).

Epidemiological analysis

For the analysis, the country was divided in 7 geographic regions, as follows: 1. Bogotá D.C., Cundinamarca and Boyacá; 2. Antioquia and Eje Cafetero (Caldas, Risaralda, Quindío); 3. Costa Pacífica (Chocó, Valle, Cauca, Nariño); 4. Santanderes (Santander, Norte de Santander); 5. Tolima and Huila; 6. Costa Caribe and Insular Territory (Cesar, La Guajira, Magdalena, Atlántico, Bolívar, Sucre, Córdoba and San Andrés y Providencia) and 7. Amazonia-Orinoquia (Amazonas, Vaupés, Guainía, Putumayo, Caquetá, Meta, Casanare, Arauca and Vichada). The geographic origin of each patient was determined on the basis of his (her) place of residence.

Cryptococcosis incidence average per annum was determined by using the population perspectives for the year 2008, the intermediate year of the epidemiological survey presented in this study (18). The mean incidence rate of cryptococcosis per annum in the general population was calculated using as denominator the total number (43,926,034) of Colombia inhabitants for the year 2008. Additionally, data on the AIDS cases was obtained from the Instituto Nacional de Salud (19); the denominator used in this case was 25,122 persons living with AIDS in the year 2008.

Laboratory assays

The identity of the isolates submitted to the central laboratories was confirmed using conventional laboratory techniques (20). Species was determined employing culture in Canavanine-Glycine-Bromothymol Blue agar (CGB) (21). The isolates were maintained in sterile distilled water and as glycerol stocks at -70 °C.

Antifungal susceptibility

These data are part of the ARTEMIS DISC Network, Global Program of the antifungal susceptibility of which the CIB participates. From 2006-2009, the susceptibility profile of 135 and 115 isolates to fluconazole (FCZ) and voriconazole (VCZ), respectively, was studied using the disc diffusion method M44-A, described by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (22). This method uses discs of 25 µg/ml of FCZ and 1 µg/ml of VCZ (Becton Dickinson, Spark, MD). Reading of the plates was done using BIOMIC, a Petri dish scanner with a digital image analyzer, which measures the inhibition millimeters and converts it into MIC using a regression curve (Giles Scientific, 1999, Santa Bárbara, CA).

Quality control was done with Candida albicans ATCC 90028 that shows an inhibition range between 32-43 mm. The results of the inhibition zones, susceptibility, MIC values and quality control data were digitally stored. Even though there are no precise criteria about the cutoff point and the interpretation for FCZ and VCZ in C. neoformans, we used the criteria published by CLSI and Barry et al (22,23) for Candida. Isolates susceptible to FCZ, had a MIC ≤ 8 µg/ml (< 19 mm inhibition), susceptible dose dependent (SDD) between 16-32 µg/ml (15-18 mm inhibition) and resistant, MIC ≥ 64 µg/ml (≤ 14 mm inhibition). As for VCZ, susceptible, MIC ≤ 1 µg/ml (< 17 mm inhibition), SDD 2 µg/ml (14-16 mm inhibition) and resistant, MIC ≥ 4 µg/ml (≤ 13 mm inhibition).

Results

During the 5 years of the study, 526 surveys were received from 55 institutions located in 22 Departments (Colombia´ s political divisions) and Bogotá, the capital city. The number of surveys submitted according to the year was as follows: 115 (21.9%) in 2006; 111 (21.1%) in 2007; 63 (12.0%) in 2008; 128 (24.3%) in 2009 and 109 (20.7%) in 2010. No surveys were received from La Guajira, Magdalena, Bolivar, Sucre, San Andrés and Providencia, Vaupés, Guaviare or Vichada.

Incidence

In the general population data obtained from the 5 years of study showed an estimated mean annual incidence rate for cryptococcosis of 2.4 x 106 inhabitants while in AIDS patients this rate rose to 3.3 x 103 (Table 1). The estimated mean annual incidence for each geographic region in which the country was divided is shown in supplement 2.

Characteristics analyzed

Table 2 summarizes the chosen patient’s characteristics, namely, demographic data, risk factors, clinical features, clinical presentation, diagnostic images, laboratory diagnosis, cryptococcal species, varieties and serotypes according to the HIV status, and treatment.

In addition, distribution of cryptococcosis patients by age according to gender is presented in figure 1. Clinical features according to AIDS status are shown in figure 2.

Circulating antigen determination

Antigen was determined in 164 CSF samples, with a global reactivity of 97.0%, as well as in 66 sera samples with reactivity of 90.9%. In AIDS patients CSF samples, titers oscillated from 1:1 to 1:8,192. In non AIDS patients, such titers ranged from 1:1 to 1:2,048. Concerning sera, titers were up to 1:1400 in AIDS - and 1:1,024 in non AIDS – patients

Antifungal susceptibility

Susceptibility data of the isolates studied is shown in table 3.

CD4+ Values.CD4+ count was informed in 104 (25.4%) surveys out of the 409 patients with AIDS; values fluctuated between 2 and 1400 cells/mm3, with a media of 52.9 cells/mm3; 87/102 (85.3%) patients had values equal or less than 200 cells/mm3, and from these 75/87 (86.2%) had values equivalent or less than 100 cells/mm3.

Relapses. Relapses were informed in 32 (0.06%) patient surveys. From these, 28 (87.5%) corresponded to HIV positive patients.

Mortality. Data were reported in 40 patient surveys at the time of diagnosis. Thirteen out of these 40 patients (32.5%) corresponded to females and 27 (67.5%) to males. From these, a total of 28 (70%) were HIV positive patients.

Data comparison between present survey and the 1997-2005 period. The most relevant data are described in table 4. Statistically significant differences were observed in the male: female ratio, which changed from 7.3:1 in 1997-2005 to 3.3:1 in 2006-2010.

Discussion

The most important issue being highlighted by this study, is the high cryptococcocal morbidity in Colombia both in immunocompetent, as well as in immunosuppressed populations, illustrating that although advances in the antiretroviral therapy have occurred, cryptococcosis is still being diagnosed in Colombia and several other countries(16,24-27).

In Colombia, the mean annual incidence of cryptococcosis is low compared with the reported in other regions of the world. In Houston, USA, the mean annual incidence reported for the year 2000 was of 0.4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants (28). In Africa, the incidence is even higher: 15.6/100,000 revealing the heavy disease burden due to cryptococcosis (29). In regions like the Northern Territory in Australia, it has been reported that the mean annual incidence per million population was 6.6 and in New Zealand, of 2.2 (30), similar to the incidence reported in Colombia. The low incidence observed in HIV patients is consistent with reports describing the changing epidemiology of opportunistic infections in persons with AIDS (31). The fact that in Colombia the overall incidence of cryptococcosis among HIV patients has not changed significantly since 1997 may well be due to modifications in the management of HIV infection itself rather than to changes in environmental exposure to the fungus or to an increase in the virulence of the pathogen (16).

A predisposition of the male gender to develop cryptococcosis, especially in the HIV infected population, here was noticed with a clear tendency towards presentation of the viral immunosuppression in males, a finding that correlates with the worldwide situation revealing that this disease is more common and more severe in young men (25,32-34). Nevertheless, because of the tendency of “feminization” of AIDS, this situation is presently changing (35), as observed when comparing our 2006-2010 period results with those obtained earlier (1997-2005) with a statistically significant difference in the proportion of women infected with cryptococcosis whose risk factor was AIDS (3.3:1 vs. 7.3:1). This observation was accompanied by a decrease in the male: female ratio, revealing the epidemiological situation of AIDS in Colombia in accordance with the reports of an increase in the proportion of women with this illness in our country (16,19).

When analyzing the data obtained for the period 2006-2010, it was observed that cryptococcosis is seen in all ages, even in the boundaries of life; between them we found 2 patients less than 15 years of age, which is in agreement with the low proportion of children known to develop cryptococcosis in global reports, even in endemic areas for this disease, except Brazil, where the prevalence in children is higher (19,9%) (16,36-39).

Clinical manifestations such as headache, mental alterations and fever, reported in the surveys analyzed in this study are similar to those informed worldwide for cryptococcosis associated with AIDS (34,35) and similar to the findings observed in the 1997-2005 period in Colombia, where 93.3% of all cases showed neurological signs (16). Interestingly data from British Columbia revealed that only 18.3% of the immunocompetent patients affected by C. gattii have had CNS involvement with most cases revealing pulmonary affection (40).

It is known that direct examination of the sample with India ink is a highly sensitive technique for detection of the blastoconidia, facilitating diagnosis of the infection. Association with culture increases the possibilities of correctly identifying the etiological agent, which is rather important for doing an on time diagnosis of the disease (41-45). We found a high positivity of direct examination and culture for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis (81.4%), which may imply that these two techniques must be done regularly in samples recovered from patients who are suspicious of having an inflammatory CNS illness.

We were able to study 413 isolates from the total of surveys received, the majority of them recovered from AIDS patients, similar to what was reported in different parts of the world, where the greater number of cryptococcosis cases in immunosuppressed patients is associated with C. neoformans var. grubii (16,24,25,34). Even though cryptococcosis in patients with impaired immunity is rarely caused by serotype B, in this study we found 2 patients with AIDS, and in the period 1997-2005, 1 of the 30 cases caused by C. gattii had HIV infection (16). Infections caused by both species of the C. neoformans/C. gattii species complex exhibit differences concerning their clinical presentation, among others; it is known that C. gattii invades the parenchyma more often than C. neoformans, and that in patients infected by C. gattii pulmonary infections are more common (5,30). However, in this study, clinical manifestations were similar in the cases attributed to either one of the 2 species, as observed in the period of time previously analyzed (16).

We found a relatively high percentage of isolates resistant to FCZ, similar to what was found by Pappalardo et al., who have reported a proportion of FCZ resistance equal to 12% in Brazil. This same author mentions several hypotheses to explain the existence of resistant phenotypes that may contribute to therapeutic failures (35). However, it is important to highlight that since there is no reference method for the determination of susceptibility tests for this pathogen, and because of the lack of studies that correlate clinical prognosis to yeast sensitivity, there is inconsistent data concerning therapeutic failure and presence of in-vitro resistant strains. Clinical condition of patients after treatment could not be ascertained from our results since this survey was intended to be completed giving only punctual information rather than more complete monitoring of the patient´s outcome after treatment had been initiated.

An important finding was that in those patients were CD4+ values were informed, 73.5% of these had levels equal or less than 100 cells/mm3; this is in accordance to the findings reported by Lizarazo et. al, who suggested that patients with low CD4+ levels represent a population at high risk of acquiring cryptococcosis (46). In this group of patients it may be useful to have a Point of Care Tests that may allow an early diagnosis of cryptococcosis, such as CrAg LFA, which helps to perform the diagnosis of infectious diseases in resource-limited settings, such as in Colombia (47).

Cryptococcal disease continues to be an important cause of death, with a 24.4% found in this study, particularly in HIV patients, showing the delay in diagnosis and calling the attention to the need to consider cryptococcal infection in the differential diagnosis of immunocompromised patients presenting with meningitis, pneumonia. On the other hand there is a need of notifying this and other events to the Colombian Public Health Surveillance System (SIVIGILA).

This survey represents an approximation to the real situation of cryptococcosis in Colombia. However, it has limitations due to the fact that it is a passive and voluntary assessment, for that reason it would require an audit to confirm the real number of cases of cryptococcosis in the participating institutions during the surveillance period. This determination is still pending at present.

The time has arrived when we should command attention in relation to diseases like AIDS and include one of its most important and serious consequences: cryptococcosis. Very few complications that may be present in advanced status of HIV-AIDS have a higher influence in morbidity and mortality than cryptococcosis. We are condemned to see very few progresses in patients affected by cryptococcosis, until we do not compromise by doing a more active surveillance so as to offer better treatments, better access to diagnostic tests and development of new research fields.

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their critical review of the manuscript.

The authors declare that no competing interests existed.

This work was supported by the Instituto Nacional de Salud, Bogotá,D.C, Colombia, and the Corporación para Investigaciones Biológicas (CIB), Medellín, Colombia.

Author for correspondence: Patricia Escandón, Grupo de Microbiología, Instituto Nacional de Salud, Avenida calle 26 N° 51-20, Bogotá, D.C., Colombia

Phone/Fax: (571) 220 7700, ext. 1421 pescandon@ins.gov.co

1.Velagapudi R, Hsueh YP, Geunes-Boyer S, Wright JR, Heitman J. Spores as infectious propagules of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 2009;77:4345-55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00542-09 [ Links ]

2. Franzot SP, Salkin IF, Casadevall A. Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii: Separate varietal status for Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:838-40. [ Links ]

3. Kwon-Chung KJ, Varma A. Do major species concept supports one, two or more species within Cryptococcus neoformans? FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:574-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00088.x [ Links ]

4. Bovers M, Hagen F, Kuramae EE, Díaz MR, Spanjaard L, Dromer F et al. Unique hybrids between the fungal pathogens Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:599-607. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00082.x [ Links ]

5. Bovers M, Hagen F, Kuramae EE, Hoogveld HL, Dromer F, St-Germain G, et al.AIDS patient death caused by novel Cryptococcus neoformans × C. gattii hybrid. Emerg Infect Dis.2008;14:1105-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1407.080 122 [ Links ]

6. Byrnes EJ 3rd, Barlett K, Perfect J, Heitman J. Cryptococcus gattii: An emerging fungal pathogen infecting humans and animals. Microbes Infect. 2011;13:895-907. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2011.05.009 [ Links ]

7. Pongsai P, Atamasirikul K, Sungkanuparph S. The role of serum cryptococcal antigen screening for the early diagnosis of cryptococcosis in HIV-infected patients with different ranges of CD4 cell counts. J Infect. 2010;60:474-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2010.03.015 [ Links ]

8. Levitz SM, Boekhout T. Cryptococcus: The once-sleeping giant is fully awake. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:461-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00113.x [ Links ]

9. Jarvis JN, Boulle A, Loyse A, Bicanic T, Rebe K, Williams A, et al. High ongoing burden of cryptococcal disease in Africa despite antiretroviral roll out. AIDS. 2009;23:1182-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832be0fc [ Links ]

10. Uribe P, Restrepo A, Díaz G. Estudio prospectivo clínico y microbiológico de las meningitis subagudas y crónicas. Antioquia Médica. 1973;23:153-64. [ Links ]

11. Greer DL, de Polanía LA. Criptococosis en Colombia: resumen de la literatura y presentación de doce casos en el Valle del Cauca. Acta Méd Valle. 1977;8:160-6. [ Links ]

12 Vergara I, Saavedra M, Saravia J, González G, Lorenzana P, Acosta C, et al. Criptococosis del sistema nervioso central. Estudio de 32 casos 1975-1991. Acta Méd Colomb. 1992;8:134-41. [ Links ]

13. Lizarazo J, Rodríguez MC. Ordóñez N, Vargas JJ, Castañeda N.Meningitis por Cryptococcus en el Hospital Erasmo Meoz de Cúcuta. Acta Neurol Colomb. 1995;11:259-67. [ Links ]

14. Ordóñez N, Torrado E, Castañeda E. Criptococosis meníngea de 1990 a 1995. Hallazgos de laboratorio. Biomédica. 1996;16:93-7. [ Links ]

15. Lizarazo J, Mendoza M, Palacios D, Vallejo A, Bustamante A, Ojeda E, et al.Criptococosis ocasionada por Cryptococcus neoformans variedad gattii. Acta Méd Colomb. 2000;25:171-8. [ Links ]

16. Lizarazo J, Linares M, de Bedout C, Restrepo A, Agudelo CI, Castañeda E, et al.Estudio clínico y epidemiológico de la criptococosis en Colombia: resultados de nueve años de la encuesta nacional, 1997-2005. Biomédica. 2007;27:94-109. [ Links ]

17. Viviani MA. Epidemiological working groups of ECMM. Mycology Newsletter. 1997;2:4-5. [ Links ]

18. Departamento Nacional de Estadísticas, Dane. Proyecciones de población. Fecha de consulta: 16 de septiembre 2011. Disponible en: http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=75&Itemid=72 [ Links ]

19. Instituto Nacional de Salud. Operación y mantenimiento del sistema de vigilancia y control en salud pública. Informe de VIH-SIDA Colombia período XII año 2010. Bogotá: Instituto Nacional de Salud; 2010. p. 13. [ Links ]

20. Ordóñez N, Castañeda E. Serotipificación de aislamientos clínicos y del medio ambiente de Cryptococcus neoformans en Colombia. Biomédica. 1994;14:131-9. [ Links ]

21. Kwon-Chung KJ, Polacheck I, Bennet JE. Improved diagnostic medium for separation of Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans (serotypes A and D) and Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii (serotypes B and C). J Clin Microbiol. 1982;5:535-7. [ Links ]

22. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Method for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of yeast. Approved guideline M44-A.2004. Wayne, Pa: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2004. [ Links ]

23. Barry A, Brown SD. Fluconazole disk diffusion procedure for determining susceptibility of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2154-7. [ Links ]

24. Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525-30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac [ Links ]

25. Dromer F, Mathoulin S, Dupont B, Laporte A. Epidemiology of cryptococcosis in France: A 9-year survey (1985-1993). French Cryptococcosis Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:82-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/23.1.82 [ Links ]

26. Sorvillo F, Beall G, Turner PA, Beer VL, Kovacs AA, Kerndt PR. Incidence and factors associated with extrapulmonary cryptoccosis among persons with HIV infection in Los Angeles County. AIDS. 1997;11:673-9. [ Links ]

27. Hajjeh RA, Conn LA, Stephens DS, Baughman W, Hamill R, Graviss E, et al. Cryptococcosis: Population based multistate active surveillance and risk factors in human immunodeficiency virus infected persons. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:449-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/314606 [ Links ]

28. Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, Graviss E, Hamill R, Brandt ME, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: An update from population based active surveillance in two large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/368091 [ Links ]

29. McCarthy KM, Morgan J, Wannemuehler KA, Mirza SA, Gould SM, Mhlongo N, et al. Population based surveillance for cryptococcosis in an antiretroviral-naive South African province with a high HIV seroprevalence. AIDS. 2006;20:2199-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b 013e3280106d6a [ Links ]

30. Speed B, Dunt D. Clinical and host differences between infections with the two varieties of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:28-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/21.1.28 [ Links ]

31. Galanis E, MacDougall L. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii,British Columbia, Canada, 1999-2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:251-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid 1602. 090 900 [ Links ]

32. Colom MF, Frasés S, Ferrer C, Martín-Mazuelos E, Hermoso-de-Mendoza M, Torres-Rodríguez JM, et al. Estudio epidemiológico de la criptococosis en España: primeros resultados. Rev Iberoamer Micol. 2001;18:99-104. [ Links ]

33. Darzé C, Lucena R, Gomes I, Melo A. Características clínicas e laboratoriais de 104 casos de meningoencefalite criptocócica. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:21-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822000000100003 [ Links ]

34. Lindenberg A de S, Chang MR, Paniago AM, Lazéra M dos S, Moncada PM, Bonfim GF, et al. Clinical and epidemiological features of 123 cases of cryptococcosis in Mato Grosso Do Sul, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50:75-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036-4665 2008000200002 [ Links ]

35. Pappalardo MC, Melhem MS. Cryptococcosis: A review of the Brazilian experience for the disease. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2003;45:299-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0036- 46652003000600001 [ Links ]

36. Moreira T, Ferreira MS, Ribas RM, Borges AS. Criptococose: estudo clínico- epidemiológico, laboratorial e das variedades do fungo em 96 pacientes. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:255-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822006000300005 [ Links ]

37. Miglia KJ, Govender NP, Rossouw J, Meiring S, Mitchell TG, Group for Enteric, Respiratory and Meningeal Disease Surveillance in South Africa. Analysis of pediatric isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from South Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;49:307-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01277-10 [ Links ]

38. Speed BR, Kaldor J. Rarity of cryptococcal infection in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:536-7. [ Links ]

39. Goldman DL, Khine H, Abadi J, Lindenberg DJ, Pirofski LA, Niang R, et al. Serologic evidence for Cryptococcus neoformans infection in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.107.5.e66 [ Links ]

40. MacDougall L, Kidd SE, Galanis E, Mak S, Leslie MJ, Cieslak PR, et al. Spread of Cryptococcus gattii in British Columbia, Canada, and detection in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:42-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1301.060827 [ Links ]

41. Pasqualotto AC, Bittencourt Severo C, de Mattos Oliveira F, Severo LC. Cryptococcemia. An analysis of 28 cases with emphasis on the clinical outcome and its etiologic agent. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2004;21:143-6. [ Links ]

42. Rozenbaum R, Goncalves AJ. Clinical epidemiological study of 171 cases of cryptococcosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:369-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/clinids/18.3.369 [ Links ]

43. Robinson PA, Bauer M, Leal MA, Evans SG, Holtom PD, Diamond DA, et al. Early mycological treatment failure in AIDS associated cryptococcal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:82-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/515074 [ Links ]

44. Saag MS, Powderly WG, Cloud GA, Robinson P, Grieco MH, Sharkey P, et al. Comparison of amphotericin B with fluconazole in the treatment of acute AIDS associated cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:83-9. [ Links ]

45. Antinori S, Galimberti L, Magni C, Casella A, Vago L, Mainini F, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans infection in a cohort of Italian AIDS patients: Natural history, early prognostic parameters and autopsy findings. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;20:711-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s100960100616 [ Links ]

46. Lizarazo J, Peña Y, Chaves, Omaña R, Huérfano S, Castañeda E. Diagnóstico temprano de la criptococosis y la histoplasmosis en pacientes que viven con el sida. Informe preliminar. Inf Quinc Epidemiol Nac. 2002;7:453-8. [ Links ]

47. Lindsley MD, Nanthawan M, Baggett HC, Surinthong Y, Autthateinchai R, Sawatwong P, et al. Evaluation of a newly developed lateral flow immunoassay for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:321-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir379 [ Links ]

48. Pappas G. Cryptococcosis in the developing world: An elephant in the parlor. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:345-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/649862 [ Links ]