Introduction

The nursing exercise has had, for years, a debt with society in the results of care that could be solved upon perceiving the conditions that hinder satisfying the social demands from nursing and ensuring quality humanized practices aimed at solving problems. The prevalence of this debt is due to deficiencies in the delivery of direct care that obstruct and restrict the duration of contacts with the patients, which is why nursing aides and relatives must offer care. Lack of time has become an unfailing argument to justify lack of quality in care1 and has led to “the absence of the application of theories to catastrophic results in care and to complaints from patients”.2 Not in vain, nurses claim the possibility of more comprehensive care, spend enough time sharing with patients, address problem solution, and develop adequate rapprochement and mutual knowledge.2

For their part, health institutions have assumed a motivation toward the market and present deficiencies in the availability and use of resources, in access to services, delays, obstacles and excessive requirements for care, shortage of staff, little regard for the quality of processes and services restricted by the pretension of obtaining maximum gains, but with scarce response to the needs of individuals, without respecting their rights or their dignity, which is why they only become means to achieve monetary objectives.3 Likewise, legislative and social proposals carried out under mercantilist mandates have not contributed at all to fulfilling the quality and humanization conditions required for care; in spite of their apparent intention of solving the problems present in society, they end up contributing to exclusion and lack of equality.4 Current social phenomena pose to Nursing the need to reconstruct care routines, guides and protocols, as well concepts, models and theories, and to recognize the sense of caring within the general context of each person’s experience.5 This concern is shared by Leininger and McFarland6 when they state that “nurses use care and have flaws in its study and explanation, of its explicit meanings and their uses and in documenting the evidence obtained from patients and nurses”. Besides, they propose that “humanistic care is essential for growth and survival and needs to be fully studied and explained to favor progress of the discipline”.6

Centering care on humanized nursing care means emphasizing on an essential attribute referred to by De Souza7 when stating: “care that is not imbricated in humanization is not care” and practicing it is not nursing. Many proposals have been made with respect to care entailing the humanized attribute and, thus, speaking of humanized care could be redundant, but in the practice of nursing there is a recognized gap with theory and, due to this, the response it gives to problems of individuals, in many cases, is not what is expected. For Da Silva and Aparecido8, humanized care should respond to the maxim “you shall love your neighbor as yourself”, but really, “there is more talk of it than what is actually done” and this is why care “is not as it should be”.

This article is part of an interpretative phenomenological study as PhD thesis conducted according to the method proposed by Munhal9 to understand the meaning of humanized care in the experiences of those who participate in it. Likewise, the work sought to establish sense beyond the definition of said care and contribute with qualitative evidence regarding the experience of said form of caring, which is what theorists propose and what people expect.

Methods

This was an interpretative phenomenological study to understand the meaning of the care experience lived by others, from the description of this practice in their own language. This research method permits “extracting the meaning of the narrative carried out based on the participant’s world, their temporality and relation with other people and their context”,9 achieved through in-depth interviews that were recorded, then transcribed and subjected to a process of organization and interpretation by the researchers. This type of interview was selected because “it liberates the description made by the person from the researcher’s influence”9 and permits variations in the phenomenon due to the context, gender or condition of each individual; additionally, it permits spontaneous development of the description. According to Munhal9, it is “an interpretative phenomenological dialogue, aimed at listening in neutral manner” in which “the participant’s way of describing is as important as the researcher’s way of listening”. The interviews lasted between one and one and a half hours; only one meeting took place with each participant. The information was recorded under conditions of privacy, and then it was faithfully transcribed and identified with a label to protect confidentiality. The label contained the letter N followed by the initials of the name to identify the nurses, the letter P for patients, and the letter S for the patients’ relatives; at the same time, a third letter was used corresponding to the middle name initial when two individuals had names starting with the same letter.

The study included 16 people: four men and twelve women between 29 and 62 years of age, selected via purposeful sampling,10 who accepted voluntary participation without receiving monetary stimuli, after receiving a telephone call from the researcher and which was possible because of data provided in snowball manner in their social and work settings. Six of the participants were professionals and employed in different areas who had been previously hospitalized due to emergency conditions or critical disease or because they required surgical interventions; seven were close relatives of patients hospitalized, and three were nurses; three of them were single and lived with their paternal families; the rest were married. Information saturation was the criterion to end participant selection, determined upon achieving a profound description of the experience. Questions, like what have you thought about the care received, permitted getting information. Doubts and each point expressed by the participants were clarified with expressions, like: I am not sure what you are trying to say. Other questions emerged according to how the interview was conducted.

Information analysis was based on the proposal by Munhal9 for interpretative phenomenological research: first, the interviews were carried out within the framework of inter-subjectivity in which each person describes their own interpretations of their experience. Second, the contents of each interview were analyzed in detail, taking note of references to the context, expressions from each subject, feelings, metaphors, and interpretations expressed in each description. The following phase analyzed the themes contained in each interview to look for coincidence in the rest. Thereafter, a narrative was written, which reflected the meanings extracted through the researcher’s interpretation process; this permitted accounting for that proposed in the objective and, besides, proposing the hourglass model to describe the results. It should be highlighted that this model was proposed based on results and not as a product of a bibliographic review or of any other type. This last step discussed the findings in light of previous studies or theoretical proposals from other authors reported in the literature. To safeguard investigative rigor, several participants were asked to read the product of the interpretation to establish the relation with what they wanted to express during the interview. Likewise, a consultant with a PhD degree revised each of the products, both interpretation and discussion of the results; also, the work was revised and received suggestions from 10 members from the research group on “Emergency and disasters” of the Faculty of Nursing at Universidad de Antioquia and received peer opinions because the results were presented to different audiences. Through prior approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Nursing at Universidad de Antioquia (Registry CEI-FE 2012-4), the study was conducted in Medellín, Colombia between December 2012 and March 2013.

Results

Humanized care: doing things well

According to what is expressed by patients, family members, and nurses participating in the study, when referring to nursing care, it should not be necessary to pin down certain attributes, given that by definition, they are implicit in it and this is precisely the case of the adjective “humanized”. Due to this, non-humanized behaviors make us think of something different from care and, consequently, if the activity nurses perform does not have that characteristic contained in the theoretical definition; it is not nursing care and obeys, rather, to impersonal care. I believe it is redundant because speaking of care in itself should include the word humanized; we are dealing with human beings, in equal terms, and that word is inherent to care. N.G.H.

Humanized care takes place between nurses and patients as human beings, aimed at doing the good for others and desiring to offer help, but it is not necessarily thus. The nurses’ tendency to freedom of thought and action could lead them at times to acting independently without consulting the other’s position, even when their actions end up affecting them in positive or negative manner: We speak of humanizing as if we had been dehumanized and turned into machines that in front of patients repeat some tasks; we care for human beings and we are humans and the intention of humanizing is trying to say let’s react because we are not giving patients visibility. N.G.H. Humanized care reflects an inclination to virtue, to acting for the good of people. When best caring and complying with the institutional and professional mission, nurses find satisfaction: humanizing nursing care means that the nurse, who is caring for patients considers them as human beings. N.J.T.

Additionally, humanized care rescues equality between nurses and patients; equality based on their humanity with their potentialities and limitations, but with different roles within a relationship that revolves around a disease experience in which one of them requests help to regain health or wellbeing and the other offers participation to accompany, help, and motivate. The condition is that nurses truly feel human and display that attitude toward others. An attitude in which whoever needs care can be in the same conditions as the nurse, as a human being. P.J.E.

Recognizing the centrality of human beings in care means assigning them a leading role, with respect to their autonomy and revising knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and practices in light of their humanity to respect it and not overlap it. It means examining the specific ways of approaching and establishing interpersonal relations in caring to reflect the patterns of personal, ethical, and aesthetic knowledge and offer true care: the added value, to humanize care, is to approach people as human beings and so: how do I approach them, do I explain and perform my interventions?. N.J.T.

An interesting expression that reflects what humanized nursing care is, was used by a participant in terms of “doing things well and with knowledge” in what refers to the very action, ways of proceeding, the opportunity in the realization and achievement of results. My definition is doing things well, with knowledge: To care for another, you have to know what you are doing and you get that through studying. It means preferring to work well and not in any manner and that is where humanization begins. P.G.M.

A condition highlighted by the participants is the physical “closeness”, the nurse’s presence and participation in all situations arising within an experience of disease with an attitude of acceptance and support: the expression of humanized service is the nurse’s relationship with the patient and the relatives, which reflects the closeness and empathy in how the nurse cares for them. S.D.E.

Approaching the patient facilitates physical and affective closeness, comprehending the situations and understanding in terms of language and attitudes, which patients and nurses show in the interactions and supposes the ability to offer friendship, affection, and acceptance, which depends on the nurse’s personal background and which can be enhanced with preparation, effort, and interest: A sick person needs someone to talk to when there is doubt, to consult about a problem, or place a complaint; someone who takes care of their pain or who shows interest in the family situation and for that one should at least have the skills to be able to approach patients, provide trust and become their support. N.G.G.

It is not an easy task to adapt to people’s demands and expectations, but it is possible to accomplish them when considering that if individuals are not equal in their daily lives and social environment, neither will they be when they are ill in a hospital; this is precisely the place to find the most special human singularities and specificities due to the illness’ effect upon cognitive functions or to a matter of taste and exercise of autonomy: Something peculiar was that he, in spite of his degree of unconsciousness, did not let female nurses undress or bathe him, but was more at ease with male nurses. S.D.E.

Patients’ oddities test nurses’ capacities to recognize and accept them or to dominate and subject them to the instructions consigned in manuals and protocols that consider individuals as equal, given that they are affected by the same disease, which does not reflect humanized care: Grandpa could not live without his hat or his teeth and I thank the nurses who allowed him to have them all the time and he was tranquil and that reassured us. S.D.E.

Impersonal care: greater interest for things

Interest for profits of some health institutions, inadequate assignment of resources, and restrictions from insurance carriers supported on legal dispositions or on bureaucratic management have led to flaws in care; this is why complaints and claims exist in society and in the collective of nurses that invite to retake the care path and recover the work of nursing with clear humanization and quality criteria: It would mean going back to our principles, to remembering that we are human beings and that we are here as equals with our patients. N.G.H.

Ignoring what humanized care is means not bringing it to practice, which justifies every effort that favors reflexion what care actually is and its meaning to people. Besides, if in the human condition it is possible to have behaviors of lack of consideration, lack of solidarity, and even wickedness, it is necessary to insist on the need for care practice with humanized orientation, without discrimination and with constant concern for defending and respecting human dignity, rights and principles of the nursing work: A recommendation for nurses, during their training and work, is to try to be human, without regard for the patient arriving. S.D.E.

Speaking of humanized care not only refers to the condition of people as human beings, but takes into consideration the qualities the nurses may have in their relationship with others, the orientation to the good, solidarity and aide to whomever needs it and interest in contributing to their wellbeing, keeping from doing harm. Humanizing care must be the main value; the humanization expected of individuals who work with others independent of their being ill. N.J.T.

It is possible to find differences in how to care for people and how care interactions are carried out; this could be logical if we consider that people are different among themselves. Often, variations on how to approach patients does not have to do with their specificities, but with the tastes and preferences of nurses who value the responses and behaviors of others, not precisely for the reason for being, but for how pleasant they can be: Human beings have certain inherent characteristics and there are people with whom it is easier to interact with than with others. P.M.E.

According to what the participants describe, communication with nurses is limited and this is another of the big motives for care to have been displaced by impersonal care: Care? Impersonal. They entered the room: good morning, I am going to apply a medication! And… good-bye! There was no… how are you? Or… how do you feel? What needs do you have? N.L.A.

It seems that questioning or evaluating were avoided to keep from engaging in any activity to solve the situation identified with the response; “ignore to avoid doing” seems to be the motto, although evaluations in nursing should be frequent because changes caused by the disease or the treatment must be detected early for their early solution. Apparently, there is more interest for things, for all types of elements existing in the unit than for patients and their relatives: The nurse would enter. Excuse me! She gathered things, changed some and removed others and exited; there was not even a word. S.R.D.

Patients and their relatives expect kindness and courtesy required in human interaction, especially when expecting to achieve therapeutic effects, as occurs in the nurse-patient relationship; however, they perceive the presence of inconvenient attitudes from the nurses that distance them affectively, hinder compliance of the work of nursing, and are taken by them as modes of punishment or sanction: I saw the chief (nurse) once and he was bad tempered; I asked him many things and he did not know or did not answer me; if I needed something, he never got it; so you say: well, what are failing at if supposedly they prepare each day!. P.M.E.

Precisely, one of those forms of punishment is the lack of nurses or their remoteness when it is considered that the patient is of “difficult control” or when the perception they have of the patient does not promote closeness because they do not acknowledge the patient’s worth as a human being or because the relationship with him is considered under conditions of inequality: She did not return; I think this is what should be requested of a professional nurse, but she never came back. S.C.O

The reasons for the nurses’ removal from direct patient care seem to be many, among them work overload and lack of time; however, it is not possible to get people not to need their help and their presence to perform procedures and obtain information or company: You are going to assign aides to perform the procedures that correspond to nurses; the administrative and care functions are our responsibility; however, the administrative is prioritized over care. N.L.A.

Delays in care and lack of response to the demands of patients and their relatives also hinder the care relationship and are interpreted as signs of lack of interest to solving problems or preventing them: I went to the nurses’ station to ask the head nurse something and she answered: ‘we’ll see you later! Two hours later I went back to tell her if I had to do whatever was necessary. That was my only contact with her. N.L.A.

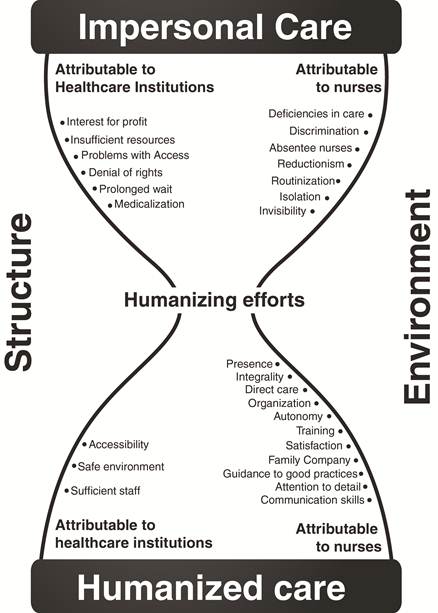

The themes that describe the relationship between humanized care and impersonal care in the experience of those who participated in the study were organized in the “hourglass” model (Figure 1), inspired on study data because that type of hourglass and problems in the humanization of care have existed over time and still remain. The exposition in the illustration lets the nursing community understand the components of each of the concepts described and their relation among them and highlights the importance of carrying out efforts to favor humanized care.

Figure 1 Hourglass model. Source: Beltrán S. OA. Memories of the 11th National Seminar on Nursing in Cardiovascular Problems and the 8th National Seminar on Neurovascular and Pulmonary Problems. Medellín: Clínica Cardio VID; 2014

The hourglass refers to the time required, besides efforts, to guide the care practice so that it permits going from the impersonal care approach, prevalent in the institutional context for many years, to favor humanized care that requires the revision of how nurses, administrators, and legislators need to proceed and even think. Time is necessary for contacts between nurses and patients to develop a culture of humanization, a way of thinking, living, and acting in function of service for whomever needs it and going beyond simple programs or campaigns with specific purposes.

The upper chamber of the hourglass represents “impersonal care”, reflected on conditions that through humanizing efforts will be intervened to achieve those that express humanized in the lower chamber. The same way the sand has limited time to go from the top to the bottom, nursing should also have a limit to advance toward humanized care because the debt with society regarding care effectiveness and results has already lasted too long.

In the “sand” position, we find the conditions that favor the impersonal orientation of care and which, as a result, produce general dissatisfaction, complaints, and claims even when these ensure growing profits for the institutions, insurance carriers, and the social system. Some of these are attributable to the social medium, like denial of rights, interest in profits, and deficiency of resources. While difficulties of access for patients and their relatives, fractioned and ‘medicalized’ care, long waiting periods, discrimination, routinization, and assigning multiple functions to nurses correspond to the institutional environment, lack of direct care, isolation of patients, focus on the physical, invisibility, and lack of interaction are related to the nurses.

On the hourglass “neck” position, we find the “humanizing efforts” that commit all the levels and will permit changing unfavorable conditions to care, orientation toward the good, and respect to human dignity. These will allow transforming the components of impersonal care into those of humanized care, like the presence of nurses at the patient’s bed side, direct and organized care, integrality in problem solving, communication skills, nurse autonomy, work and personal satisfaction, information, caring for details, training, family accompaniment, and accessibility to nursing care during illness. Given that humanizing efforts are essential to accomplish change, they occupy a central and important position in the model. The hourglass’ supports, which give it shape and hold its position are the institutional structure and the social medium that are determinant to guide the orientation of care because its approaches influence upon the work nurses carry out, given that they are subjected to a system of oppressions that limit their autonomy and professional independence.

Discussion

The results of this study permitted the researchers to gain understanding of humanized care, reflect and become conscious of the strengths in the work of nursing, as well as of their weaknesses and errors, and propose the hourglass model. This task is highlighted by Nietzsche’s famous phrase: “improvement will only be invented by he who knows how to say: this is not good. Interest in understanding care and its attributes, like humanization, is compatible with that expressed by Roy et al.,11 who state that “in spite of the rich history of development of knowledge in nursing, ambiguity persists on the discipline’s central unifying focus” to articulate “what we are and what we offer”. Due to this, the authors propose, “facilitating humanization, election, quality of life, and care for living and dying”. Not in vain, it is possible to find that care has diverse determinations, as seen in the study, but without clarity in its meanings, which - in turn - influences upon the lack of forcefulness of the proposals by the nurses to improve care.12 Also, it generates a certain turbulence in how the nursing discourse is constructed, revised, and updated and its relation with the practice and the economic and political environment that increasingly complicate care.1 What is indeed clear is that nurses and the discipline are responsible for the practice and they are not allowed to be indifferent because “legitimizing care is a true necessity, even within a social medium in which there is no radical freedom”.13 According to Fawcett,14 nurses could be facing “a period of great ambivalence on the fundamental nature of the profession” in whose solution contribution can be attained from “participation from educators, practitioners, researchers, manuscript and research reviewers, nursing journal editors acting as defenders of the specific knowledge of the nursing discipline”. Similarly, Moreno15 proposes highlighting the interest in the proposals by nursing theorists embodied in models and theories “that describe nursing phenomena from a humanist perspective to broaden knowledge on care as a phenomenon of interest”.

“Doing well everything related to care” proposed by the participants refers to complying with the work and responding to the expectations of those requiring care, which “contributes to promoting trust”.16 This aspect is referred to by Aranda and Brown17 when they state: “Nurses are too clever to care for you”, an expression that could have at least two contradictory readings and which establish the orientation to the humanization of care or to impersonal care. First, that it would be an advantage and what individuals expect due to the condition of intelligent is that is recommendable to trust in care from nurses who are capable of responding to each situation. Second, and this would be reproachable, that in the name of said intelligence care is disdained and nurses consider themselves worthy of something higher or better, guided by the affirmation that “basic care in a non-essential component of the nursing knowledge and practice” and, consequently, nurses “act as supervisors and consider said care as a function of laborers with less skills,17 which results in the absence of nurses in direct care and scarce professional visibility.

The “close presence of nurses” refers to their presence by the patients, recognized by many theorists in nursing, as well as by the study participants, as a requisite for care because it favors interactions. In this regard, to contribute to said presence and, hence, to closeness with patients in the physical and relational spheres, it is recommendable to refrain from “delegating interactions with patients and emotional support or the procedures and interventions related to nursing; if care is imperceptible it could favor replacement of nurse by other less-skilled and less costly individuals”.16 According to Nelson and Gordon,1 generic workers and care assistants diminish autonomy and threaten the integrity and credibility of nurses.

The ability to interact with people makes it necessary to reflect on some important aspects in nurses for humanized care, understood as a relational activity: the first relates to the ability to speak and communicate through oral and sign language, likewise, to understand the messages and expression of ideas, feelings, and emotions of others. The second indicates that it is “fundamental to consider a more humanized proposal of care no as an obligation, but as an act of respect and solidarity, aimed at rethinking and reconstructing actions and to creating innovations to favor human life”,18 which would suppose controlling the tendency to routinizing and mechanizing care and subjecting individuals to uniformity, bearing in mind the disease they are enduring or the procedures required; disavowing, in any case, the individuality and importance of the patterns of ethical and aesthetic knowledge.

The way patients, family members and nurses perceive care varies according to conceptual, cultural, and contextual differences. According to Larson,19 “knowing the differences between the nurses’ perceptions and those of patients on behaviors is important” because it is not difficult to see that nurses have a marked tendency to conducting activities on the patients’ physical plane, possibly as a reflection of a comfortable and reductionist position given that “physical work is easier to carry out and it is delivered as a response to the few demands from patients”, according to that reported by Lövgren et al.,20 and, consequently, patients’ perceptions do not favor nurses because they “acted as if the work were only a job, as if their routines were inflexible and demonstrated indifference towards the other person’s condition”.

Losing sight of the conditions and demands for humanized care reduces the work of nurses, according to that expressed by the participants, to impersonal care”; this is also referred to by De Faria et al.,21 upon stating that “human beings go on to be treated as one more case and their individual problems are ignored and their relatives excluded” within a reductionist relationship in which the patient is seen as a simple object. This relationship is characterized by how the patient is dehumanized and the disease, as the focus of care by health professionals, is brought to the status of subject.

Authors, like Roy et al.,11 have referred to the difficulties of nurses and institutions to respond to patients and society; a response related to delays and deficiencies in care, interest in things more than in people and the work overload reported by the participants. They state that an aspect that definitely influences is “the medicalization of the work of caring and the institutional approach that privileges economic gain and control of expenses at the expense of human wellbeing”11 that are definitely in force in the current hospital system. Likewise, Weinberg12 states “institutions distort the conditions for care upon reassigning the functions appertaining the profession to the least skilled and qualified personnel”. Heartfield5 complements this discussion upon stating “hospital policies cut times for nurses” under the motto “quicker and sicker”, that is, care more quickly for more people, which causes diminished time of interaction that is the crucial factor to establish and maintain trust, mutual understanding, and solution of problems.” This restriction diminishes the possibility of caring and interacting with patients and poses a new dilemma, between disobeying the hospital dispositions substantiating the need for care or becoming involved with that policy of doing more with less, delegating on the family, and proposing new homecare schemes integrating informal caregivers and family members to promote self-care. This last option results compatible with the function of supervisors who assumed the nurses and have contributed for the hospital bed to be seen as a means for profit and not as a care environment5. Within this hospital scheme, we fail to see that assuming functions that do not correspond to the work of nurses or caring simultaneously for a group of patients that exceeds physical and temporal capacities leads to difficulties in performance: “diverse studies report that for each patient added to a nurse’s workload, increased mortality of 7% is associated;22) in turn, association exists between complete team of nurses and lower frequency of adverse events in hospitalized patients”, as well as “between their educational level and low frequencies of mortality, infection, and flaws in rescue”, as stated by Needleman et al.,23 that is, problems in care decline when the nursing group increases and when it is offered better trained nurses22.

The researchers also reported that “inasmuch as institutions and insurance carriers exert financial pressure on care, nurses have increased their dissatisfaction for hospital conditions and safety and quality have deteriorated”.23 In this regard, Fawcett14 proposes the possibility that “nurses have fallen in love with the thought of seeing themselves as the victims of physicians and health administrators and became fond of accusing them of oppressing and not permitting the practice of autonomy”. This could “contain the explanation to the fact of having reached the point of discarding the very discipline of nursing in favor of developing and using knowledge from other disciplines; however, this does not explain why some of the basic procedures in nursing have been discarded”.14

In view of the gap between what care is and what it should be, efforts have been made in hospital settings with participation from academic institutions where, with studies and investigations, it has been possible to describe and understand many of the problems arising in the nursing practice, revising interests in the formation of nurses and proposing new approaches in education. Initially, it was thought that “teaching of humanization in undergraduate nursing assignments stemmed from the premise that human beings have biological and physiological needs and attitudes aimed at satisfying them were considered humanized and the dehumanized attitudes ignored them”;24 nevertheless, from reflections by nurses it has been understood that “recognizing merely the bodily needs would be insufficient to care for a human being and the proposal is to consider the psychological needs, as well as respect, affection, and sympathy in care interactions”.24 Batista et al.,25) highlight the importance of some approaches that seek humanized care in institutions propitiating conditions for patients and nurses that favor a practice of higher quality and of better results upon proposing that “nursing care, if applied properly, besides being profitable, provide great quality of life”; not in vain, in “magnetic” hospitals registered nurses assume the responsibility of caring and the results obtained in costs and patient satisfaction are quite satisfactory”.

The conclusion of this study is that in the experience of the participants, the relationship with nurses may be lived in two manners entre which there is a complex incompatibility: one of them is humanized care and the other is impersonal care whose presence is dependent of aspects pertaining to the social and legal system, health institutions, and nurses, which, in turn, go from the orientation to wellbeing to interest in capital or problems in using resources and personnel and involve personal attitudes and interests. The relationship between these two concepts is understood as vicariant, that is, one replaces the other according to how the relationship is guided with the individuals and the environment provided. Humanized care, for nurses, patients, and their relatives participating in the study does not depend exclusively on the will of nurses, but on the collective commitment that also involves the social context and health institutions and can displace impersonal care if efforts are channeled, in this case humanizers, toward said purpose. For its part, the impersonal relationship displaces care when the collective effort aims at profits and gains by following social guidelines that seem imperative currently. The hourglass model describes the relationship between these two forms of healthcare.

text in

text in