Introduction

Gastrointestinal leaks and fistulas are serious and potentially life-threatening conditions that can be seen as a wide variety of clinical presentations. Leaks are mainly related to postoperative anastomotic defects and are responsible for an important part of surgical morbidity and mortality. Leaks and postoperative collections can lead to the development of a fistula between two epithelial structures. Interventional endoscopy with stent placement plays a fundamental role as first-line and salvage treatment in these situations, as it is an effective and minimally invasive method in which a customized and multidisciplinary approach is required based on clinical presentation, defect characteristics (size, location), local experience and device availability. Leakage is defined as a pathological communication between intra- and extraluminal compartments, while fistula is defined as an abnormal communication between two epithelialized surfaces (1,2.

Most gastrointestinal leaks and fistulas (75%-85%) occur as a complication of intra-abdominal surgery and are caused by a variety of factors including absent or improper placement of drains, malnutrition, inadequate surgical technique, infection and anastomotic dehiscence. A smaller percentage occurs secondary to inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, neoplasms, trauma and radiotherapy (3.

Fistulas can be difficult to diagnose and frequently require surgical interventions; thus increasing morbidity and mortality and hospitalization costs, therefore, the main principles of treatment are identification of the defect site, drainage and prevention of additional collections, either by diverting the flow of luminal contents or closure of the defect (4,5. Although traditional surgical or conservative management with bowel rest, intravenous antibiotics and nutritional support are the mainstays of treatment, they are not always effective (6-8. Endoscopic management has proven to be an effective and less invasive alternative to primary surgery, and fully or partially covered self-expandable metallic stents are a minimally invasive alternative in the management of gastrointestinal leaks and fistulas, whose objective is to prevent the leakage of gastrointestinal contents through the fistulous tract, thus allowing the defect to heal, which favors the patient to resume oral nutrition and improve his nutritional conditions, therefore allowing the closure of the defect and, in the future, improving the quality of life9,10).

One of the disadvantages of metallic stents is that they can cause hyperplasia of the adjacent mucosa, which makes them difficult to remove once fistula closure has been achieved (10. Uncovered or partially covered stents are more associated with epithelial hyperplasia and other complications, especially when their use is transient, such as for the management of benign conditions. Therefore, the use of fully coated metallic stents has been favored for this indication, although they may have a higher migration rate (11.

Blackmon et al. reported data from a prospective study with a 15-month follow-up, which included 25 patients, 23 of them were diagnosed with anastomotic leaks, tracheoesophageal fistulas and benign perforations and subsequently managed with covered metallic stents as the first line of treatment. Ten patients were cured, who were managed with stents for anastomotic leaks after gastric bypass or gastric sleeve. One patient with three iatrogenic esophageal perforations was controlled with stent placement, and 2 out of 4 patients had their tracheoesophageal fistulas sealed with the use of stents. Stent migration was reported as the most frequent complication in 10 patients12.

The retrospective series of Tuebergen et al. included 32 patients, 24 with postoperative leaks mostly after gastroesophageal oncologic surgery, and 8 patients with nonmalignant esophageal perforation. They achieved a complete functional seal after stent deployment in 78 % of the cases with the use of fully covered metallic stents, and it is noted that the positioning was performed on average between 3 and 5 days after diagnosis (13.

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate closure rates in the management of gastrointestinal fistulas with self-expandable metallic stents, and the secondary objective is to determine early and late complications and hospital stay.

Materials and methods

A retrospective evaluation of the databases of interventional procedures in the gastroenterology division was performed from January 2007 to December 2017, there were 11 patients with a diagnosis of esophageal fistula, 10 of them were treated with a self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) and 1 with SEMS plus OVESCO (Over The Scope Clip) in the gastroenterology division of the Hospital Universitario San Ignacio. All data was recorded in a format designed for this purpose, before and after stent placement. Follow-up was done by reviewing medical records or by telephone contact.

Regarding the baseline diagnosis, two cases reported a history of adenocarcinoma and one case a squamous cell carcinoma of the distal third of the esophagus (3 cases, 27%). In 6 cases (55 %) there were adenocarcinomas of the cardia (1 case) or gastric corpus (5 cases), one case of obesity surgery (9 %) and one case of perforated metastatic cervical cancer (9 %) (Figure 1). Derived from the previously described underlying pathologies, the most frequently performed surgical management was total gastrectomy plus Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy (45.5 %), followed by esophagogastrectomy plus esophagogastric anastomosis (36.4 %).

Clinical parameters were recorded using a Microsoft Excel database, describing technical success, clinical success, procedure-related complications such as SEMS displacement, mortality, and length of hospital stay. Follow-up was performed on patients with endoscopic and radiological studies.

Informed consent for the procedure was obtained from all patients or their relatives, in case the patient could not give authorization due to the clinical condition at the time. In all patients, the SEMS placement was performed under sedation provided by anesthesiology, with strict monitoring of vital signs. The location of the esophageal defect was marked for identification under fluoroscopy on the surface of the skin with a radiopaque identifier. Then, a semi-rigid guidewire was inserted into the esophageal lumen under endoscopic vision and left in situ with removal of the gastroscope. A fully or partially covered nitinol stent was inserted over the guidewire, which was released under fluoroscopic and endoscopic vision. The location of the fistula was verified to be in the middle part of the SEMS (technical success) by upper GI endoscopy.

The SEMS was removed at about 4 weeks in all patients who had evidence of healing in the fistulous tract, which was corroborated by performing an upper gastrointestinal x-ray. Clinical success was defined as the absence of symptoms (dyspnea, cough, expectoration and dysphagia), with normalization of serum markers of inflammation, and endoscopic or radiological evidence of control of fistula production.

Results

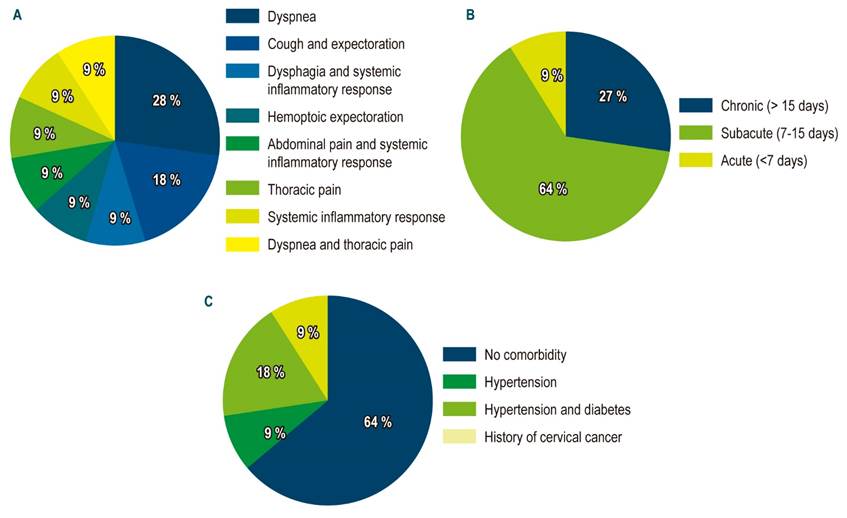

Fourteen SEMS were placed in 11 patients, which were distributed in 6 women (54.5 %) with an average age of 58 years (standard deviation [SD]: 16.02), with a minimum of 36 years and a maximum of 86 years. Regarding the comorbidities found, most patients had none (63.6 %), two patients had high blood pressure (HBP) and diabetes mellitus (18.2 %), one patient with high blood pressure and another one with a history of cervical cancer. Regarding the clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study (Table 1), it was found that the main symptom was the presence of dyspnea in 3 cases (27.3 %), followed by cough in 2 cases (18.2 %) and the remaining 6 patients had different symptoms, which are shown in Figure 2. The evolution time of symptoms in most cases was subacute (7-15 days; 63.6%), followed by chronic symptoms (> 15 days; 27.3%).

Table 1 Characteristics of the Clinical Diagnosis

Figure 2 Clinical characteristics of the study subjects. A. Symptoms for consultation. B. Symptom evolution time. C. Comorbidities.

The most frequent finding during follow-up was pleural effusion (36.4 %) and the diagnosis of fistula was made in most cases (45.5 %) with esophagogram. In 2 cases with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and computed tomography (CT) of the chest (18.2 %), and in the remaining 4 cases with esophagogram and EGD, esophagogram and CT scan of the chest, EGD and methylene blue, each of them respectively (Table 1). The most reported type of fistula is related to esophagoenteric anastomosis (45.5 %), followed by esophagopleural fistula (36.4 %), said patients were managed with SEMS.

Regarding the endoscopic management of the fistula, it was found that the average time of SEMS insertion since the diagnosis was made was 6.5 days, and the totally covered SEMS was the most used (in 54.5 % of the cases), followed by partially covered SEMS (in 36.4 % of the cases) and partially covered SEMS plus OVESCO (in 9.1 % of the cases). The OVESCO clipping system was used to close the defect and it was protected with a SEMS.

All procedures were technically successful and symptom resolution was observed in 72.7% of cases. The duration in situ of the SEMS had an average of 33.67 days, although it should be noted that this data was not defined in 5 patients since they died with SEMS in situ. The only complication reported was the displacement of the SEMS (27.3 %) and out of these, one patient required repositioning of the SEMS on 3 occasions due to displacements (Table 2). The average hospital stay was 41,5 days. The resolution of the fistula was observed in 63,5% of the cases. No deaths related to fistula, leakage, or SEMS implantation were reported.

Table 2 Characteristics of the surgical procedure.

According to the characteristics of the patients in whom there was no resolution of symptoms after endoscopic management of the fistula (Table 3), the 3 patients who were clinically unsuccessful were male and had no comorbidities. These 3 patients had no acute symptoms, 2 of them had adenocarcinoma of the distal third of the esophagus as initial diagnosis and the third patient had diffuse adenocarcinoma of the gastric corpus.

Table 3 Characteristics according to the clinical success of the surgical procedure.

In 2 cases, total gastrectomy plus Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy was performed, and in the other case, subtotal esophagogastrectomy plus esophagogastric anastomosis was performed; 2 cases had esophagopleural fistula and the other one had tracheoesophageal fistula. Two of the SEMS used in the clinical failure were fully covered and the other one was partially covered. In addition, two of the cases presented displacement as a complication.

Regarding the time of SEMS insertion from the diagnosis of the fistula, on average, it was two days less in successful cases than in failure cases, and the mean hemoglobin value was lower in patients who had no clinical success.

Discussion

Esophageal fistulas have a wide spectrum of presentation, ranging from non-specific symptoms such as dyspnea or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) to severe patient compromise, due to sepsis secondary to empyema or mediastinitis, reason why the treatment must be individualized. Considering the unfavorable results after surgical reintervention in the case of anastomotic fistulas, such management has been increasingly displaced and less invasive managements such as endoscopic interventions with clipping implantation, OVESCO or SEMS, have been considered as the first choice (4,5,9.

To date, no consensus has been reached on the adequate treatment of esophageal fistulas; however, case reports and small series have been published in which endoscopic management with SEMS has been the mainstay of treatment in different pathologies associated with fistula (14-17. Our case series describes situations of high complexity such as esophagotracheal and esophagobronchial fistulas, which were managed by experienced endoscopists, which explains the high technical success rate and the mortality rate was low in relation to SEMS implantation, compared to other published series (Table 2).

In this case series the mortality rate in relation to SEMS was 0 %, significant in comparison with other studies, which may be related to the lack of surgical intervention, which may increase mortality after SEMS implantation due to the clinical condition of the patient (14,18-20. Furthermore, another of the justifications for the low mortality and the technical and clinical success observed in our patients is related to the time of SEMS implantation from diagnosis, which plays a fundamental role, as was successfully demonstrated in patients who were managed with SEMS implantation in the first 2 days after diagnosis, compared to those who received such management after 2 days, thus fully justifying that early SEMS implantation significantly reduces the morbidity and mortality of this potentially lethal pathology. Therefore, once an inadequate evolution is observed in a patient, the performance of an EGD or radiological study should be evaluated as soon as possible for timely diagnosis and management.

It should be taken into account that the endoscopic management of esophageal fistulas is complex from a technical point of view and has wide implications in economic terms, given that the implantation of the SEMS is not the only procedure performed, bearing in mind that additional studies are required, such as repetitive EGDs and radiological studies, until a precise diagnosis is obtained and the diagnosis and resolution of the fistula is clear.

It is important to consider the type of SEMS to be used. Partially or fully covered SEMS are used in the management of esophageal cancer, anastomotic fistulas and iatrogenic esophageal perforations, with adequate success21,22, but doubts have been raised about the long-term efficacy of SEMS due to their complications23, such as the embedding to the esophageal wall, so endoscopic removal can be complex23-25. In our case series, the SEMS was removed in 6 patients without complications after confirmation of resolution of the fistula, bearing in mind that the removal of the SEMS must be done carefully due to the risk of perforation and bronchoaspiration during the procedure.

In our case series, fistula closure was 63.3 %, slightly below of what is described in the literature, which can be attributed to distal migration (which occurred in 27.3 % of our cases) and to the time of SEMS implantation after the fistula diagnosis was made; however, mortality was 0 % in relation to SEMS implantation, with a mean hospital stay of 41.5 days, which is related to the clinical condition of each patient.

It is worth to take into account combined endoscopic techniques, such as the use of cyanoacrylate, endoscopic suturing, vacuum techniques (Endo-SPONGE®) and OVESCO in this type of fistula; the latter was used in our case for closure of the defect and subsequently protected with a partially covered SEMS. Combined techniques are increasingly accepted with favorable technical and clinical success rates, as described by Thiruvengadam et al. in their retrospective cohort (26.

In conclusion, based on the results and that reported in the literature, it can be affirmed that endoscopic management of esophageal fistulas or leaks with SEMS is an effective and safe alternative, with improvement of symptoms, high closure and low risk of complications.

text in

text in