Introduction

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare disease characterized by the presence of large, extensive intestinal lymphatic vessels, leading to the loss of lymphatic fluid into the intestinal lumen. This condition results in severe hypoalbuminemia and consequently generalized edema1. PIL was first described in 1961 by Waldmann, who observed varying degrees of lymphatic vessel dilation in 18 patients2. The etiology of PIL remains unknown; however, several genes, including VEGFR3, PROX1, FOXC2, and SOX18, are implicated in the development of the lymphatic system3.

PIL can be suspected at birth or during pregnancy based on ultrasound imaging, which can detect fetal ascites or lower limb lymphedema2. In a child with symptoms suggestive of PIL, routine tests typically indicate hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. The diagnosis is confirmed through endoscopy, which reveals the characteristic snowflake appearance of the affected duodenal mucosa, and histological examination of biopsies showing lymphatic vessel dilation4.

The primary treatment strategy for PIL involves dietary modification, specifically a low-fat diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides (MCT)2. When dietary measures are insufficient, dietary supplements or enteral nutrition based on fat-free formulas or formulas with MCTs5 as the main lipid content are utilized5. In cases where dietary interventions fail, additional options can be considered, either alone or in combination with a low-fat diet and MCT supplementation2. Second-line therapies include surgical interventions (ranging from laparoscopic resection to major surgery such as duodenopancreatectomy), radiological interventions, and medications. The choice of treatment depends on the extent of the disease6. The prognosis of PIL can be severe and potentially fatal, particularly when malignant complications (such as lymphoma) or pleural or pericardial effusions occur2.

Case presentation

The patient is a two-month-old girl with a prenatal diagnosis of ascites identified on a third-trimester ultrasound, which led to a planned cesarean section. She was born weighing 3500 grams and was discharged with furosemide and instructions for exclusive breastfeeding. At one and a half months of age, she presented with an increased abdominal circumference and had five episodes of food vomiting, leading to her hospitalization.

On physical examination, the following data were recorded: weight: 6.8 kg, height: 60 cm, weight/height index (+2SD) unreliable due to ascites, mid-upper arm circumference (-3SD) indicating severe malnutrition, and abdominal circumference: 53 cm. The abdomen displayed a collateral venous network and was globular, tense, with a positive fluid wave and crescent-shaped dullness. The remainder of the examination was apparently normal.

Paraclinical test results were as follows: white blood cells: 4900/μL, neutrophils: 41.8%, lymphocytes: 39.9%, hemoglobin: 11 g/dL, platelets: 531,000, fibrinogen: 351 mg/dL, total proteins: 4.9 g/dL, albumin: 3.4 g/dL, globulin: 1.5 g/dL, urea: 9.1 mg/dL, creatinine: 0.21 mg/dL, cholesterol: 138.9 mg/dL, triglycerides: 5512.6 mg/dL, C-reactive protein (CRP): 0.28 mg/dL, immunoglobulin A (IgA): 0.2 g/L, immunoglobulin G (IgG): 2.2 g/L, immunoglobulin M (IgM): 0.4 g/L, immunoglobulin E (IgE): 3.4 IU/mL, alpha-fetoprotein: 434 IU/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen: 1.5 ng/mL, CA 125: 568.1 IU/mL, CA 15-3: 6 U/mL, CA 19-9: 10 U/mL, fecal fats: positive. The ascitic fluid study showed a milky white appearance, albumin: 0.8 g/dL, amylase: 16 U/L, glucose: 133.5 mg/dL, proteins: 2.7 g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): 442 U/L, white blood cell count: 0.209 cells/mL, lymphocytes 79%, neutrophils: 21%, ascitic fluid culture: negative, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) and GeneXpert in ascitic fluid: negative.

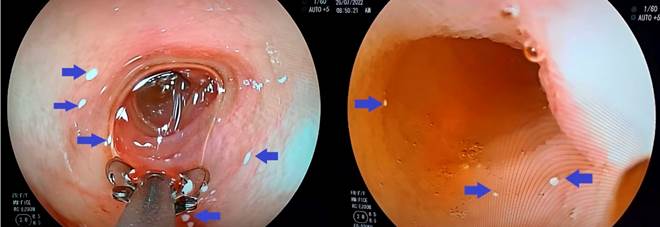

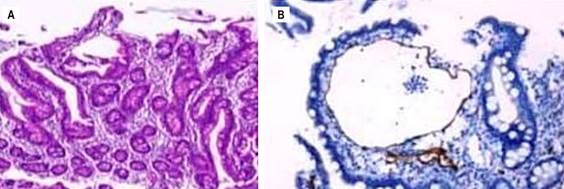

Imaging studies included a chest-abdominal X-ray, which revealed abundant free fluid. Both the abdominal ultrasound and the triphasic abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1) indicated marked ascites. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed snowflake-like images in the first, second, and third portions of the duodenum (Figures 2A and B). Duodenal biopsy revealed villi with a preserved crypt-villus ratio (greater than 2.5/1), and no increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (less than 30%) was observed with routine techniques. Slightly dilated mucosal and submucosal lymphatic vessels surrounded by scant lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate were noted in the lamina propria of some villi, without macrophages suggesting xanthomatous lesions. Immunohistochemical staining with podoplanin (D-240) highlighted lymphatic vascular structures in isolated villi, findings consistent with focal duodenal lymphangiectasia (Figures 3A and B).

Source: Patient’s medical records.

Figure 1 Triphasic abdominal CT scan showing homogeneous parenchyma of the liver and spleen, pancreas with a normal tissue attenuation pattern, normal kidneys, spontaneous ascites, bilateral posterobasal subsegmental pulmonary atelectasis, and no identifiable tumors.

Source: Patient’s medical records.

Figure 2 Endoscopic images of the first, second, and third portions of the duodenum displaying white speckling with a snowflake appearance that does not disappear with pressure washing. Pathological findings are indicated by blue arrows.

Source: Patient’s medical records.

Figure 3 A. Duodenal mucosa. B. Histological sections of duodenal biopsy with podoplanin (D2-40) immunohistochemical staining highlighting lymphatic vascular structures in isolated villi.

Upon admission, the patient received an intravenous dose of albumin at 1 g/kg and was started on prophylactic cefazolin before the diagnostic and therapeutic paracentesis. A milky fluid of 370 mL was obtained (Figure 4), prompting the initiation of octreotide infusion at 1 μg/kg/h along with total parenteral nutrition (TPN). This regimen was maintained initially and later increased to 3 μg/kg/h due to refractory ascites. Several evacuative paracenteses were performed, draining volumes up to 900 mL, with concurrent albumin administration for replacement. Due to the unavailability of formulas with exclusive medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) in the country, an extensively hydrolyzed formula containing MCT was used. Subsequently, the octreotide infusion was switched to subcutaneous administration at 100 μg every eight hours, which allowed the discontinuation of parenteral nutrition after 25 days of hospitalization. On day 26, the patient was discharged with an abdominal circumference of 38 cm and treatment that included an extensively hydrolyzed formula, MCT, subcutaneous octreotide, spironolactone, fat-soluble vitamins, and folic acid. During follow-up in the outpatient service, she required hospitalization once more for a therapeutic paracentesis, but she continued to show favorable progress.

Discussion

PIL is a rare disease, and the prevalence of its clinically manifest form is unknown due to the presence of asymptomatic cases. Few cases have been reported in Latin America, and none in Ecuador. In children, it is generally diagnosed before the age of three but can present later in childhood or even in adulthood(2).

The main clinical manifestation is peripheral edema of varying degrees, which is usually symmetrical. However, moderate serous effusions such as pleural effusion, pericarditis, or chylous ascites are common and can be life-threatening in severe forms2. In this case, the patient presented with ascites detected on ultrasound during pregnancy, which was already a warning sign for appropriate management at birth. Unfortunately, adequate management was not initiated until she was one month old, by which time the ascites had become severe.

Although several methods have been proposed to investigate PIL, none can replace the histological examination of biopsies for confirming the diagnosis2. Routine imaging tests at the onset, such as abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), can typically identify diffuse thickening of the small intestine wall and edema, which are consequences of dilated lymphatic vessels within the villi2.

Diet modification is the cornerstone of PIL treatment, involving a high-protein diet (2 g/kg/day) and low-fat content (< 25 g/day). The fat component should consist of more than 90% MCTs and short-chain triglycerides SCTs because these components are transported directly to the portal circulation instead of the lymphatic system, thereby decreasing intestinal lymphatic flow and preventing the rupture of lymphatic vessels with the resultant loss of proteins and T cells2,6. TPN allows for digestive rest and a reduction in splanchnic and subsequently chylous flow. TPN is not recommended as an initial nutritional support measure but is an option for patients who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to oral feeding, do not respond to dietary treatment, have an underlying disease requiring more aggressive nutritional therapy, or are malnourished5.

Other treatment options depend on the extent of the disease. Focal segmental PIL refractory to dietary therapy can be treated by intestinal resection or radiological embolization. Diffuse intestinal lymphangiectasia and extensive lymphangiectasia require treatment with drugs such as octreotide, propranolol, and tranexamic acid6.

Octreotide is a somatostatin analogue that decreases splanchnic blood flow, intestinal motility, and triglyceride absorption. Therefore, it can be optimally used in patients with intestinal lymphatic vessel involvement only6. Complete resolution of chylous effusion has been observed after initiating octreotide therapy in newborns7. An induction therapy with a subcutaneous injection of 1 to 10 μg/kg/dose twice daily for two weeks is recommended, followed by the same dose injected subcutaneously at four-week intervals as maintenance therapy6. However, in our patient, we initially opted for an octreotide infusion, which has shown good response in cases of congenital chylothorax, before transitioning to subcutaneous administration at doses up to 40 μg/kg/day8. Albumin infusion is a symptomatic treatment proposed for patients with significant ascites9 or severe lower limb edema, but its effectiveness is transient due to persistent lymph leakage into the intestinal lumen2.

Other therapeutic options include propranolol, which appears to have a therapeutic effect on the endothelium of lymphatic vessels6. Tranexamic acid has demonstrated utility, as intestinal protein loss can occur during increased fibrinolytic activity10.

Recommendations

Healthcare professionals should be made aware of the suggestive symptoms of this rare disease to facilitate early and appropriate intervention, thereby improving the quality of life for these patients. No other cases of PIL have been reported in Ecuador, making it important to note that the treatment was successful despite local challenges.

text in

text in