Introduction

Belching is the audible release of air from the esophagus or stomach into the pharynx1. It is a physiological event that typically occurs up to 30 times a day2. Although common in the general population, it can be considered a disorder when it becomes excessive and bothersome1. Patients who are unable to control their belching in public may feel embarrassed, disrupting their social life and negatively impacting their quality of life2,3. These are the patients who most often seek medical consultation for their symptoms3.

Studies report the prevalence of belching symptoms in the general population, with rates ranging between 6.7% and 28.8%3. One study found that approximately 3.4% of patients with upper gastrointestinal discomfort referred to a gastrointestinal physiology unit had supragastric belching (SB)4. However, the results can vary depending on the definition of excessive belching3.

Belching can occur in isolation or be associated with other gastrointestinal complaints such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), rumination syndrome, or functional dyspepsia2. It has also been linked to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. The advent of technologies and advances in impedance monitoring and high-resolution esophageal manometry have improved our understanding of belching5. The aim of this study is to present a case series from our experience at a gastrointestinal physiology referral center in managing patients with SB using diaphragm rehabilitation, alongside a review of the literature.

Materials and Methods

Consecutive patients referred to the gastrointestinal motility laboratory at the GutMédica Institute in Bogotá, Colombia, from January to December 2021, aged 18 years or older, were included in this study. These patients underwent 24-hour esophageal pH-impedance monitoring (pH-IIM) without proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) due to frequent belching as their predominant symptom, whether or not it was associated with typical GERD symptoms. Patients who were taking PPIs or had a history of esophageal or gastric surgery were excluded. Prior to the test, typical symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) and atypical symptoms (belching, dysphagia, cough, throat clearing, and globus sensation) were assessed using a standardized questionnaire. Patients presented for the exam after fasting for at least eight hours.

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) was located manometrically, and a catheter with impedance sensors at 3, 5, 7, 15, and 17 cm, and a pH sensor 5 cm above the upper edge of the LES, was used. Monitoring lasted at least 20 hours, and patients were given a diary to record symptoms during the study period. They were instructed to maintain their daily activities, meal schedules, and normal sleep patterns.

Data from the impedance and pH channels were stored on portable equipment by Sandhill Scientific or Sierra. The traces were reviewed, and manual editing was performed by expert gastroenterologists who noted meal events and symptom recordings. Meal periods were excluded from the analysis. A supragastric belching (SB) event was defined by an increase in impedance moving in a caudal direction from the proximal to the distal channel, followed by a return to baseline, starting in a retrograde manner from the distal channel.

Patients with frequent SB underwent diaphragm biofeedback therapy, with a protocol of one to two sessions per week, each lasting 45 minutes. The sessions were individualized, focusing on the specific needs of each patient, and were conducted by the same clinician. The treatment included an assessment to identify the patterns triggering the belching. Next, patients were educated about the nature of their symptoms to promote awareness and understanding of the factors causing them. During the therapy, techniques were applied such as postural correction, manual therapy for diaphragm release aimed at restoring proper mobility during breathing phases, and respiratory pattern awareness with an emphasis on diaphragmatic breathing. This included phonorespiratory coordination, myofunctional exercises for phonoarticulatory muscles, glottis training, vocal orientation and training exercises, and swallowing exercises designed to limit air entry into the esophagus. All exercises were focused on controlling the air entry and exit from the esophagus during daily activities.

A symptom evaluation was performed before and after the therapy sessions via a telephone survey, using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (0-3: mild, 4-6: moderate, 7-10: severe). A significant response was defined as a VAS improvement from severe to mild, while a partial response was considered when the change was from severe to moderate or from moderate to mild.

Case Presentation

Fifteen patients (8 women), aged between 21 and 70 years, are presented. In 33% of the patients, reflux hypersensitivity was evident, while 66% did not have pathological acid reflux. On average, seven (range: 3-20) diaphragm biofeedback therapy sessions were conducted. A significant response was observed in 66% of the patients, with better outcomes reported as the number of therapy sessions increased. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of Patients with Supragastric Belching

| Age | Sex | Esophageal pH-Impedance | AET | Number of Belches | Number of Therapy Sessions | Significant Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.2% | 10 | 7 | Yes |

| 60 | F | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.2% | 33 | 9 | Yes |

| 32 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.1% | 17 | 3 | No |

| 32 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.5% | 27 | 5 | Yes |

| 60 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 1.3% | 38 | 7 | Yes |

| 26 | M | Reflux hypersensitivity | 1.1% | 56 | 3 | No |

| 30 | F | Reflux hypersensitivity | 1.9% | 16 | 3 | No |

| 21 | F | Reflux hypersensitivity | 0.5% | 36 | 9 | Yes |

| 52 | F | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.1% | 16 | 3 | No |

| 27 | F | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.1% | 18 | 7 | Yes |

| 61 | F | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.1% | 10 | 3 | No |

| 70 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.4% | 24 | 10 | Yes |

| 49 | M | Negative for pathological acid reflux | 0.3% | 211 | 20 | Yes |

| 22 | F | Reflux hypersensitivity | 1.3% | 27 | 5 | Yes |

| 31 | F | Reflux hypersensitivity | 0.1% | 26 | 10 | Yes |

Author’s own research.

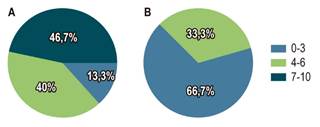

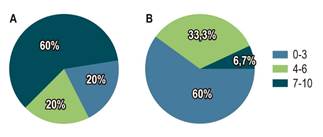

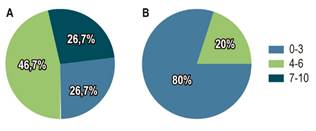

Eighty-six percent of patients showed improvement in the symptom of excessive belching (Figure 1); 73% reported improvement in their family environment (Figure 2); 66% reported improvement in their work environment (Figure 3); 74% experienced improvement in their social environment (Figure 4); and 94% achieved self-control over their belching.

Author’s own research.

Figure 1 Symptom Discomfort. A. Discomfort before therapy. B. Discomfort after therapy.

Author’s own research.

Figure 2 Discomfort in the Family Environment. A. Discomfort in the family environment before therapy. B. Discomfort in the family environment after therapy.

Author’s own research.

Figure 3 Work Environment Interference. A. Interference in the work environment before therapy. B. Interference in the work environment after therapy.

Physiology of Belching

With each swallow, a variable volume of air is ingested and transported to the stomach5. During belching, the accumulated intragastric air is vented into the esophagus, after which it may be expelled through the mouth5. The motor events of belching consist of three independent phases that are coordinated with each other: the gastric gas escape phase, the upper barrier elimination phase, and the gas transport phase6. The gastric gas escape phase involves a gastro-LES inhibitory reflex, causing transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which is triggered by distention of stretch receptors in the proximal stomach6. The upper barrier elimination phase involves transient relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) along with airway protection, activated by stimulation of rapidly adapting mechanoreceptors in the esophageal mucosa6. The gas transport phase is reverse esophageal peristalsis, mediated by elementary reflexes, and is believed to be triggered by rapidly adapting tension receptors in the serosa6.

Classification and Pathophysiology

There are two different types of belching: supragastric belching (SB) and gastric belching (GB). SB is considered an unintentional response to an uncomfortable sensation in the abdomen or retrosternal region, which does not occur during sleep, speech, or moments when the patient is distracted. Over time, SB can become a learned behavior for the patient2.

In supragastric belching, air rapidly enters the esophagus, followed immediately by its quick expulsion. Two theories explain its mechanism:

Air suction method: There is a movement of the diaphragm (in a proximal direction) that increases negative intrathoracic pressure, similar to what occurs during a deep inspiration. During SB, the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxes, the glottis closes, and air flows from atmospheric pressure in the pharynx to subatmospheric pressure in the esophagus. This esophageal air is then expelled orally, with the patient perceiving it as a belch6-8.

Air injection method: There is a simultaneous increase in pressure in the pharynx that initiates air entry into the esophagus. The pressure gradient is caused by elevated pharyngeal pressure, without any change in intraesophageal pressure. This can be due to increased pressure or contractions at the base of the tongue, and esophageal peristalsis does not occur (no simultaneous contraction of the esophagus)7,8.

GB is considered a physiological mechanism and occurs due to the rapid release of air from the stomach secondary to transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This mechanism prevents excessive abdominal distention from swallowed air2.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made through clinical evaluation and a thorough history taking. This helps to rule out the presence of red flags that may suggest organic causes, such as dysphagia or weight loss, and to assess the frequency and clinical pattern of the belching. Conditions such as GERD or anatomical abnormalities that may be involved must be ruled out4,5. In some cases, invasive investigations are unnecessary, as during the consultation, the patient may present with frequent and repetitive belching, suggestive of supragastric belching (SB). Gastric belching (GB) is neither rapid nor repetitive1,8.

According to the Rome IV criteria, belching disorders are classified into two types: excessive SB and excessive GB (Table 2)(1). The term aerophagia (frequent air swallowing), previously considered a mechanism of belching disorder under the Rome III criteria, was removed in the latest version of Rome IV because not all cases result from air swallowing(1).

Table 2 Diagnostic Criteria for Belching Disorders According to Rome IV Criteria

| Belching Disorders |

|---|

| Diagnostic Criteriaa |

| Must include all of the following: |

|

Belching from the esophagus or stomach occurring more than three days a week (severe enough to impact usual activities) Excessive supragastric belching (from the esophagus) Excessive gastric belching (from the stomach) |

| Supporting Comments |

| Supragastric belching is supported by the observation of frequent and repetitive belching. |

| Gastric belching has no established clinical correlation. |

| Objective intraluminal impedance measurement can be used to distinguish supragastric belching from gastric belching. |

aCriteria present for the previous three months with symptom onset at least six months before diagnosis. Adapted from: Stanghellini V, and colleagues. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1380-13921.

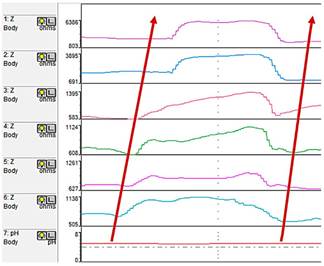

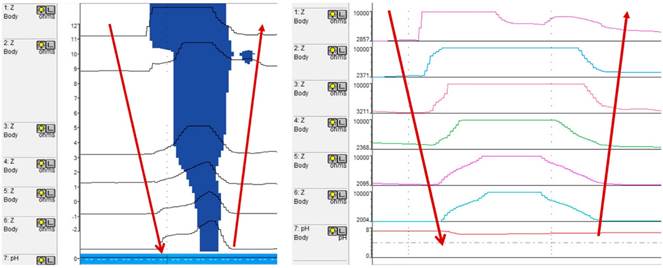

The gold standard for diagnosis and classification is 24-hour impedance-pH monitoring, which allows differentiation between the two types of belching and distinguishes them from GERD9. The esophageal impedance catheter is based on Ohm’s law, which states that impedance to current flow is inversely related to the medium’s electrical conductivity. As a result, this device can detect liquid or air refluxed into the esophagus based on changes in electrical conductivity, regardless of whether the content is acidic or non-acidic9. The transit of intraesophageal content can be detected through sequential changes in impedance along the catheter. Impedance monitoring plays a key role in the study of belching, as the conductivity of air is very low, and the presence of air between the electrodes results in an increase in impedance. Additionally, the direction of air flow must be evaluated. In GB, an impedance increase begins in the distal channel and progresses toward the more proximal channel, while in SB, the impedance increase begins in the proximal channel and progresses toward the distal channel (Figures 5 and 6)7-10.

Figure 5 Gastric belching: Increase in impedance begins in the most distal channel and progresses toward the most proximal channel. Air is expelled from the esophagus in the oral direction, and impedance returns to baseline from the distal to the proximal channel (the arrows indicate the direction of airflow). Adapted from: Kessing BF, and colleagues. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1196-2037.

Figure 6 Supragastric belching: Increase in impedance begins in the proximal channel and progresses toward the distal channel. Air is expelled from the esophagus in the oral direction, and impedance returns to baseline starting from the distal and ending at the proximal channel (the arrows indicate the direction of airflow). Adapted from: Kessing BF, and colleagues. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1196-2037.

Treatment

The most important aspect is establishing a strong doctor-patient relationship, in which the mechanism behind the belching is clearly explained during the consultation. In most cases, patients expect an explanation of their condition and hope to find an organic cause; however, in the absence of an organic etiology, some patients may disagree with the information provided4,5.

Currently, behavioral therapy and speech therapy are considered the most effective treatments for this condition11-17. Proper diagnosis with pH-impedance monitoring helps confirm that a behavioral disorder is present, which gives patients a clearer understanding of their symptoms and facilitates behavior modification and deconditioning7,10. The mechanism of air suction or injection into the esophagus should be explained to the patient to prevent its repetition and to achieve smooth breathing patterns. This is accomplished through exercises that train the glottis, vocal cords, and breathing10. Since SB is a learned behavior, behavioral therapy is useful. A recent clinical trial involving 42 patients with SB found that behavioral therapy reduced the frequency and intensity of belching at six months, with a 75% response rate to the therapy13. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has positive effects that persist for at least six to twelve months after treatment14.

Additionally, speech therapy and biofeedback can help reduce excessive belching15. Abdominal breathing exercises can be taught by having the patient place a hand on their abdomen during breathing, ensuring that the hand moves throughout the respiratory cycle. This shifts attention from the belching to the behavior associated with it, fostering a cognitive process that is crucial for successful therapy. It is believed that 10 to 20 sessions are needed to achieve a significant reduction in belching complaints, although this is not yet standardized7,8. Conducting therapy guided by impedance monitoring may facilitate the correlation of symptoms with real-time visual information, helping to improve patient understanding and motivation. However, the catheter can be uncomfortable and might reduce adherence to therapy10.

It is important to practice daily exercises that include breath-holding through glottic tension, with both laryngeal and oral closure, while redirecting the patient’s attention away from the belching toward the actions that precede it. The patient can observe themselves in a mirror, or in some cases, videos can be used to document the events10. Exercises should be performed to improve abdominal breathing, ensuring that it is smooth and calm, avoiding sudden stops. These exercises should be practiced both at rest and while speaking. Additionally, in cases of severe, persistent belching, the technique of breathing with a finger between the teeth can be used, along with phonation exercises to reduce subglottic pressure and tension in the laryngeal muscles, and appropriate diaphragmatic breathing. The laryngeal-cricopharyngeal-lingual complex is also studied to unlearn ineffective actions like movements of the tongue, larynx, and upper esophagus, through jaw relaxation exercises, laryngeal manipulation, effective articulation, and vocal techniques. If suboptimal swallowing is present, activities are performed to improve oral preparation, optimize the transport phase, and coordinate swallowing with breathing10,15.

Another behavioral therapy method involves teaching the patient to breathe with the mouth open and the tongue positioned behind the upper incisors, combined with slow, conscious diaphragmatic breathing in 3-second inhalation and exhalation cycles. These exercises should be practiced at least twice daily for three to four minutes in both the supine and upright positions. After this initial process, the exercises should be performed daily and as frequently as possible to prevent belching by recognizing warning signs of when belching might occur. The response to these therapies is subjectively recorded using visual analog scales (VAS) and quality-of-life questionnaires, which have shown improvements in perceived belching severity and quality of life in more than 50% of published studies11. Sustained glottic opening can improve by up to 75% at three months, and the therapy can be performed in the office10,16. This therapy involves slow, diaphragmatic breathing with the mouth open, starting in the supine position and then sitting to prevent belching. If successful, the patient is advised to repeat this sequence at home16. Finally, hypnotherapy has been used anecdotally with good results18.

The only pharmacological treatment that has shown efficacy is baclofen, sometimes in combination with pregabalin. By reducing transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations, it also decreases reflux events and may influence the mechano- and chemosensitivity of the esophagogastric junction. However, these medications can cause excessive drowsiness, and due to their side effects, they are infrequently used19,20.

Conclusion

Belching is a physiological event; however, for some patients, it can become a medical issue due to its excessive or difficult-to-control occurrence. Belching may occur in isolation or be associated with other gastrointestinal disorders such as GERD, rumination syndrome, or functional dyspepsia. Impedance monitoring assists in the accurate classification of belching. The most important aspect is a strong doctor-patient relationship, where the mechanism behind the belching is clearly explained to the patient. Psychoeducation is a therapeutic option since SB is a learned behavior. For the treatment of SB, diaphragmatic biofeedback therapy is an effective strategy. Other available alternatives include behavioral and speech therapy.

text in

text in