Introduction

Intestinal pneumatosis is defined as the presence of gas within the intestinal wall, which can affect the small intestine, the colon, or any layer of the intestinal wall1. Its pathogenesis is not well understood; it is idiopathic in 15% of cases and serves as a secondary manifestation of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal diseases in 85% of cases2. We report a case of colorectal lymphoma presenting with intestinal pneumatosis among its clinical, endoscopic, and imaging features. The patient was treated with the R-CHOP regimen, resulting in disease remission and clinical improvement.

Clinical Case

The patient is a 59-year-old male, previously healthy, with no relevant personal or family medical history. He presented with a 30-day history of fatigue, weakness, generalized abdominal pain primarily in the right iliac fossa, up to 12 daily episodes of diarrhea, each with associated rectal bleeding, and a weight loss of six kilograms.

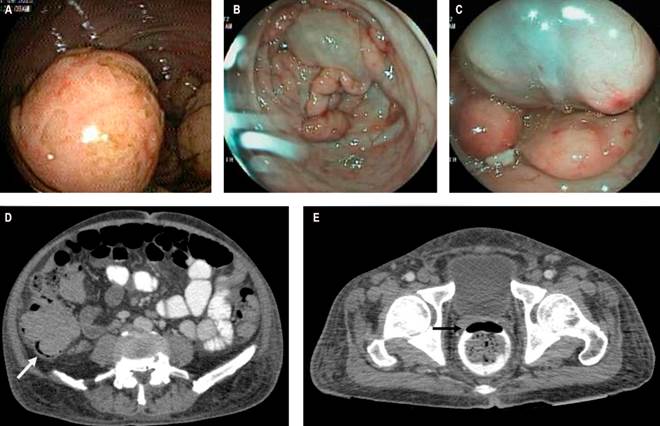

On admission, his hemodynamic parameters were normal, with documented generalized abdominal pain, most pronounced in the right iliac fossa, but without signs of peritoneal irritation. Admission tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin [Hb]: 8.1 g/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (2.6 g/dL). A total colonoscopy showed multiple solid masses in the cecum, sigmoid colon, and rectum, affecting the mucosa and appearing submucosal, ranging from 15 to 40 mm in size, friable and non-collapsible, surrounding a large, soft, 6-cm mucosal cyst that was compressible on biopsy forceps contact. Biopsies were taken from the solid lesions. The remainder of the colon also displayed multiple cystic lesions, with larger ones observed in the rectum (Figure 1A, B, and C).

Thoracic CT imaging revealed no lesions. Abdominal CT showed cecal wall thickening with a thickness of 16 mm and thickening of the right posterolateral rectal wall, reaching a thickness of 15 mm, with a clear image of pneumatosis at this level (Figure 1D and E). Adjacent pericolic lymphadenopathy was seen near the ascending and transverse colon, with diameters up to 10 mm, associated with some cystic lesions of the colonic and rectal walls. Gastric antrum thickening was also observed, prompting an esophagogastroduodenoscopy with endoscopic findings suggestive of gastric lymphoma, from which biopsies were taken. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry results were compatible with mantle cell lymphoma (blastoid variant) in the stomach, cecum, sigmoid, and rectum.

Author’s File.

Figure 1 A. Ulcerated solid lesion. B. Cystic lesion surrounded by multiple solid lesions. C. Cystic lesion with pale blue mucosa compatible with colonic cystic pneumatosis. D. Cecum occupied by a solid mass with pneumatosis of its wall (white arrow). E. Pneumatosis image in the rectal wall (black arrow).

Treatment was initiated with the R-maxiCHOP regimen by the hematology-oncology service, resulting in a favorable response. The final assessment via positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed a complete metabolic response, with no evidence of colonic cystic pneumatosis.

Discussion

Intestinal pneumatosis is a condition of variable etiology characterized by the presence of gas within the intestinal submucosa or subserosa3. It was first described by Du Vernoi in 1783 and later named pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis by Mayers in 18254. In 1952, Koss presented a comprehensive series of 213 cases of intestinal pneumatosis, characterizing the condition and concluding that it is 3.5 times more common in men than in women2. Its incidence remains unknown due to the asymptomatic course observed in a high number of patients1.

In terms of etiology, 15% of intestinal pneumatosis cases are idiopathic, while 85% are secondary2. Various theories have been proposed to explain its pathogenesis. The mechanical theory suggests that gas dissects the intestinal wall through small mucosal lacerations or via the serosa, following the path of the mesenteric vasculature5. The bacterial theory posits that gas-producing bacteria reach the submucosa through small mucosal disruptions6. The biochemical theory supports the presence of pathogenic hydrogen-producing bacteria that increase intraluminal pressure due to excess gas, facilitating its migration into the submucosa, where it becomes trapped7.

The diagnosis of intestinal pneumatosis is generally radiological and can be visualized on plain abdominal X-rays; however, tomography is more sensitive and can help document underlying conditions causing it8. Typical findings in colonoscopy include polypoid submucosal cysts covered by pale blue mucosa, which rapidly deflate upon puncture or biopsy7. Colonoscopy also allows for the identification of other mucosal lesions, such as polyps or tumors.

Most patients do not require specific treatment3. Patients presenting with intestinal pneumatosis alongside signs of peritonitis, metabolic acidosis, hyperlactatemia, or portal venous gas benefit from surgical exploration9. For patients who do not require urgent surgical intervention, management depends on symptom severity. Asymptomatic patients do not require treatment7. For patients with mild symptoms, antibiotics (such as metronidazole) and treatment of the underlying cause are recommended10. Oxygen supplementation and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have also been proposed to increase venous partial oxygen pressure, reduce partial pressure of other gases, and promote a diffusion gradient across the cyst wall. However, the precise dosage and duration required for complete resolution are not well defined7,11. Elemental diets have been used with relative success, aiming to alter the intestinal microbiota and inhibit gas-forming bacteria7,12.

Lymphomas have been documented as an underlying cause of intestinal pneumatosis; however, most of these cases present with intra-abdominal complications that necessitate urgent surgical exploration, such as intussusception, stenosis, or free perforation due to colorectal lymphoma13-16. There are also limited reports of colonic cystic pneumatosis associated with lymphoma, which resolves after receiving specific quadruple therapy for lymphoma16. It remains unclear whether imaging should be repeated to document the resolution of intestinal pneumatosis, although some authors recommend it17.

This case presents colonic cystic pneumatosis as a manifestation of gastrointestinal mantle cell lymphoma. Its significance lies in the fact that, in 85% of cases, pneumatosis is secondary to an underlying disease, necessitating a comprehensive patient evaluation. The colonic pneumatosis resolves once treatment for the underlying condition is provided.

Conclusions

Intestinal cystic pneumatosis is a condition marked by gas deposits in various layers of the intestine and often reflects an underlying morbid condition.

Diagnosis is generally radiological and should be supplemented with endoscopic evaluation, with the full clinical picture considered to guide treatment.

Colonoscopy reveals submucosal cysts covered by pale blue mucosa that deflate upon puncture or biopsy.

Reported etiologies include immunosuppression, medication associations, and gastrointestinal tract neoplasms, including lymphomas.

Treatment options include oxygen supplementation, elemental diet, antibiotics, and addressing the underlying condition if identified.

text in

text in