Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia

Print version ISSN 0121-246X

Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq vol.25 no.2 Medellín Jan./June 2014

ORIGINAL ARTICLES DERIVED FROM RESEARCH

EVALUATION OF ORAL HYGIENE IN PRE-SCHOOL CHILDREN THROUGH BACTERIAL PLAQUE SUPERVISION BY PARENTS

Jairo Corchuelo Ojeda1, Libia Soto2

1 Dentist, Ph.D. in Public Health. Associate Professor, School of Dentistry. Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. E-mail addresses: jairocorcho@yahoo.es, libisotto@hotmail.com

2 Dentist, Specialist in Pediatric Dentisrty and Preventive Orthodontics. Full Professor. School of Dentistry Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia

SUBMITTED: JUNE 11/2013-APPROVED: SEPTEMBER 10/2013

Corchuelo J, Soto L. Evaluation of oral hygiene in pre-school children through bacterial plaque supervision by parents. Rev Fac Odontol Univ Antioq 2014; 25 (2):.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: parents are the greatest influence on childrens lives and there is a close connection between parents practices and their childrens behavior. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of bacterial plaque supervision by parents on oral hygiene of children in grade 0. METHODS: this was a non-controlled trial to evaluate the response to intervention within the same group of subjects by recording plaque index before and after the intervention. The study included 32 schoolchildren, 18 girls and 14 boys, aged 5.6 years on average. RESULTS: This study assessed the effectiveness of parental plaque supervision on children of grade 0 from Juan Pablo II School. The group that presented adherence levels higher than 75% was formed by children of 5 years of age; plaque index showed significant differences in weeks 8, 12, 18, 20, 24, and 28 (p < 0.05). The group with adhesion levels between 51 and 75% included children of 5 and 6 years of age, and the plaque index evaluated up to week 18 presented significant differences during the evaluated weeks (p < 0.05). The group with adhesion levels between 26 and 50%, with children over 5 years of age, showed that plaque index until week 12 presented significant differences in all the evaluated weeks (p < 0.05). CONCLUSSION: parents can systematically monitor their childrens oral hygiene by using instruments such as community plaque index (CPI), which helps to reduce plaque levels.

Key words: primary prevention, tooth brushing, oral hygiene, dental plaque

INTRODUCTION

In developing countries, the emergence of dental caries is on the rise and the health care services have limited capacities to assist the entire population.1 Studies conducted in Valle del Cauca (Colombia) on 982 preschool children aged 4 years on average evidenced a rate of 41.3% plaque; 28% of these children had cavities without cavitation, 35% presented caries with cavitation, and 31% had gingivitis.2

Empirical evidence shows that parents are the most significant influence on childrens lives and that there is a direct association between the parents personal practices and their childrens behavior.3 Children learn brushing habits from their parents and teachers. Unfortunately, little research has been conducted on the role of parents as oral health educators. It seems that mothers social norms with regard to childrens oral hygiene behavior have not been sufficiently established.4

Traditionally, schools have been the place where children receive dental health education. Therefore, some researchers have made efforts to strengthen school programs that include parents participation.5

In reducing periodontal problems, it has been found that self-care is essential for periodontal health. If the individual is not willing to maintain reasonable levels of regular and consistent oral care at home, the benefits of treatments provided by oral health professionals will be reduced.6

Educational interventions have experienced considerable advances, from the simple provision of information to the use of complex programs involving strategies of psychological and behavioral change. The objectives of interventions have also been extensive, thus, knowledge, attitudes, intentions, beliefs, behaviors, the use of dental services, and oral health status have all been subject to change.7

Studies carried out in the 1980s and 1990s came to the conclusion that dental health education resulted in improved dental health behavior and better objective indicators of oral health status (reduction of plaque and gingival bleeding). However, it was less effective in changing attitudes and knowledge.8

Studies conducted by Scandinavian scholars showed significant associations between oral hygiene and dental caries, especially in smooth tooth surfaces.9 These findings motivated the researchers to promote hygiene programs. Taking into account that the necessary skills and perseverance in maintaining adequate levels of oral hygiene may exceed the average capacity of children, they considered necessary to start with supervised teeth cleaning programs. These efforts were documented, demonstrating significant effect in reducing gingivitis and caries in children and adults.10 Few similar efforts to prevent both tooth decay and gingivitis have been replicated in the literature of other Western countries.11

The European Workshop on mechanical plaque control approved the following policy statement in 1998: "forty years of experimental research, clinical trials and demonstration projects in different geographical and social environments have confirmed that the effective elimination of dental plaque is essential for dental and periodontal health throughout life. Therefore, we recommend that this be reflected in the development of explicit national and community oral health promotion policies".12

The effect of oral plaque parental supervision on pre-school childrens oral hygiene is still unknown. The objective of this study was to describe its effect on oral hygiene in children of grade 0 (preschoolers) from Juan Pablo II School (Cali, Colombia) through recordings of bacterial plaque by parents.

METHODS

This was a non-controlled trial to evaluate the response to intervention within the same group of subjects, by recording plaque index before and after intervention performed by parents on children enrolled in grade 0 at Juan Pablo II School. In this study, each participating child was its own control subject. The evaluated children were not compared with other groups.

The study was approved by the board of directors of Juan Pablo II School, the coordinators of Siloé Health Center and Ladera Health Network (Cali, Colombia), and by the parents of participating children.

In total, 32 schoolchildren participated, 18 girls (56%) and 14 boys (44%), aged 5.6 years on average (standard deviation 1.1). The study did not include children with systemic diseases (such as leukemia, cancer or respiratory infection) or acute lesions in the oral cavity (abscesses, dental pain, herpes, etc.).

Community plaque index (CPI) was recorded using a clinical instrument provided by the Pacífico Siglo XXI Research Group of Universidad del Valle School of Dentistry. In standardizing community plaque index, the obtained concordance was 80% (Kappa Index). CPI was recorded on forms from Monday through Saturday, and each Thursday these forms were handed in to the groups coordinating teacher, who in turn gave them to the research team in charge of consolidating plaque levels weekly.

For three weeks, the parents were trained on basic aspects of oral hygiene at Juan Pablo II School. They were taught how to perform bacterial plaque control with CPI and they were standardized on this instrument. For plaque registration, parents asked their children to rinse with a mouthwash containing a plaque disclosing solution for 30 seconds, and then they observed teeth surfaces, according to the community plaque index guidelines. Records were taken during 33 weeks, the time of permanence of the group with the highest adherence.

The primary measured variable was community plaque index (CPI), a variable that depends on oral-hygiene promoting actions such as brushing at least three times a day. CPI was registered every day in between lunch and dinner.

The parents were asked to record CPI around four hours after lunch or before dinner and to provide brushing instruction after registering the data in order to improve oral hygiene in the areas stained with the revealing substance.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the studys distribution of variables. We found out that the variables presented normal distribution, and therefore we used parametric statistics (Students T test). Significance was established by first suggesting as alternative hypothesis that, following parental intervention, childrens CPI differs from that before the intervention. A level of significance of 5% alpha was established, and Students T test was chosen to interpret values.

The estimators were calculated taking into account the study's design and using the statistical program SPSS® version 17.

RESULTS

The 32 participating children were 5.6 years on average, with 1.1 standard deviation. 56.3% of the children were 5 years old, 21.9% were 6 years, and 21.9% were older than 6. The average number of teeth was 21, distributed as follows: 43.8% of children had 20 teeth, 21.9% had 24 teeth and 12.5% had 22 teeth.

By the time the study started, community plaque index was 38.2, which is considered an average oral hygiene index. 40.6% of preschoolers under evaluation had good oral hygiene (community plaque index lower or equal to 25%). Figure 1 shows that over time the number of preschool children with better plaque control increased.

Figure 2 shows the weekly observations, taking community plaque index as reference average, as measured by parents on their children enrolled in grade 0 at Juan Pablo II School.

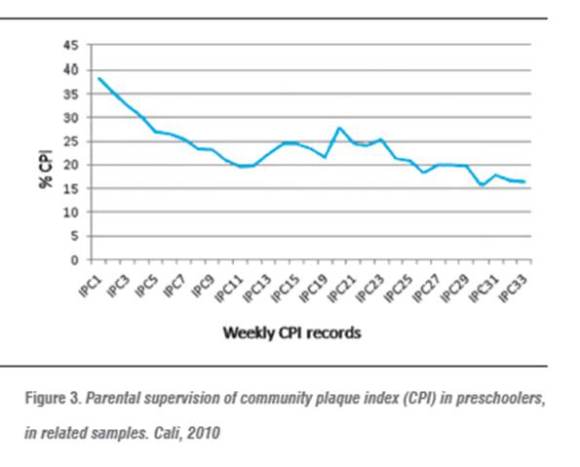

By analyzing the statistical data in CPI related samples per week, we observed a decrease in plaque index, adjusted to the active population in the sample (figure 3).

By comparing the initial community plaque index with indexes grouped by month, one may observe continuous decrease during the months of September, October, November, and December, with a slight increase in January of the following year, and then a decrease until the month of April, by the end of the study.

Parents adherence to the program was characterized by a group that remained in the study for 12 weeks (50% of participants); a group that stayed 16 weeks (21.9% of participants); a group that remained 33 weeks (15.6% of the participants) and a group that participated for only 3 weeks (12.5% of the participants).

The group with adherence levels over 75% included children of 5 years of age (80%), with a total of 20 teeth per child. Data analysis using the t test for related samples by comparing initial plaque index with the records every 4 weeks up to week 28 yielded significant differences in terms of bacterial plaque reduction in weeks 8, 12, 18, 20, 24, and 28 (p < 0.05).

The group with adherence levels ranging from 51 to 75% included children of 5 (57.1%) and 6 (42.9%) years of age. The total number of teeth per child in 85.7% of the preschoolers was 20 to 22. Data analysis using the t test for related samples comparing initial plaque index with records every 4 weeks until week 18 yielded significant differences in terms of bacterial plaque reduction in all the evaluated weeks (p < 0.05).

The group with adherence levels ranging from 26 to 50% included children of 5 years of age (50%) and older (50%). 81.2% of these children had 20 to 24 teeth. Data analysis using the t test for related samples comparing initial plaque index with records every 4 weeks until week 12 yielded significant differences in terms of bacterial plaque reduction in all the evaluated weeks (p < 0.05).

The group with adherence levels lower than 26% included children of 5 years of age (50%) and older (50%). 75% of these children had 20 to 24 teeth. Data analysis using the t test for related samples comparing initial plaque index with records every 4 weeks until week 3 yielded no significant differences in the evaluated weeks (p < 0.05).

According to the parents, the reason for poor adhesion was lack of time due to changes in working or home changes due to economic reasons.

DISCUSSION

A significant decrease was observed in bacterial plaque index measured by parents on preschoolers from Juan Pablo II School, in the city of Cali, going from 38.2% average index (poor hygiene) to less than 20% (good or acceptable oral hygiene). The proportion of children with good oral hygiene at the beginning of the study was 40% and it increased to 80% in the group with the highest adherence levels. The role of parents in controlling their preschool childrens plaque resulted in improved oral hygiene of children during the evaluated school year. Oral health policies for this population group should include plaque supervision by non-dental staff, such as parents or other people close to the childs environment.

With the use of CPI, previous studies in the region detected levels of plaque very similar to those found in this study, although we must bear in mind that CPI standardization in community homes2 was 7% when performed by dentists versus 15% inter-examiner error when done by parents. A study conducted in 2003 on schoolchildren from 20 Valle del Cauca municipalities showed a significant reduction in children's plaque levels when plaque supervision and oral hygiene habits promotion were done by primary school teachers (15% CPI inter-examiner error).13 The participation of teachers and parents supports the hypothesis of not including non-dental staff in plaque control as being effective and efficient in oral health promotion programs. These findings also support the inclusion of professionals other than dentists and dentistry staff (such teachers, nurses, physicians, health educators, etc.), who must be provided with materials and knowledge if they are to offer basic information and guidance on oral hygiene promotion. Just as a pediatrician is not required to explain how to clean a babys body, a dentist or a hygienist are not needed to explain how to clean the proximal, posterior, and lingual surface of the teeth.11

The first years of life are important in the formation of essential healthy habits for personal life and interpersonal relationships, such as proper nutrition, hygiene, personal order, and social life.14 Personal care programs at early ages play a preventive role in educating healthy children or timely detecting all sorts of difficulties. The participation of the family and the school is vital in implementing education models, by proposing behavior changes, developing cognitive processes, and promoting active participation in order to strengthen the relations with the health system.15 Interventions should start as early as possible in order to obtain even more effective results;16 therefore, it is recommended to start oral hygiene education with mothers and kids in health centers and programs.17

In this study, the group with the most adherence levels to bacterial plaque parental supervision was that of five-year-old kids. Most participating parents stayed in the program for at least 12 weeks. All the participating groups experienced significant plaque reduction each additional week of the plaque control program, in relation to initial plaque index. We think this is the result of the parents interest not only in oral hygiene recommendations, but also in their daily commitment to showing the kids those areas that require better brushing. This reduction might also be connected with the kids perceiving their parents interest in taking good care of their teeth.

The influence of North American schools on the regions dental curricula have encouraged the studies on the use of fluoride and sealants instead of promoting bacterial plaque control, unlike the British and Scandinavian studies. The present study confirms that it is possible to contribute to bacterial plaque reduction in preschool children, with potential additional benefits in reducing tooth decay and gingival diseases.18

Our study also shows that after the December holidays there is a slight increase in the level of plaque, but it goes back to the decreasing phase as the process of education in oral health habits is resumed by parents, as well as bacterial plaque supervision.

The socioeconomic status of participating parents was low, and this study did not inquire into their education level. These variables should be studied in populations with different socioeconomic levels, as previous studies have found that the education level and income affect childrens health care.19

In relation to the factors influencing parents permanence in this study, our findings are similar to those of studies that inquired about the ability of parents to care for their childrens oral health.19 The positive outcomes of this interventional study with no control group must be validated with trials including control groups, in order to improve the scope of the study.

One of the limitations of this study is that it only took into account the pre-school population without a control group, excluding other preschoolers with other types of intervention, and failing to include comparisons to determine if the intervention variable "parent" was the most important one in reducing bacterial plaque in children. Despite this, the findings provide some bases for decision-makers and for relevant plans.

CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that parents participation in promoting oral hygiene habits, measuring its effectiveness through bacterial plaque supervision, and using an instrument such as community plaque index,20 resulted in a decrease of plaque in preschoolers, passing in a short period from poor to good oral hygiene.

REFERENCES

1. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Evaluación decenal de la iniciativa regional de datos básicos en salud. Washington: OPS, 2004. [ Links ]

2. Corchuelo J, Casas RA. Línea base en salud oral en preescolares de seis municipios del Valle del Cauca en el 2010. Informe final. Cali: Fundación Ceges; 2010. [ Links ]

3. King JM. Patterns of sugar consumption in early infancy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1978; 6: 47-52. [ Links ]

4. Blinkhorn AS. Influence of social norms on toothbrusing behaviour of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1978; 6: 222-226. [ Links ]

5. Lee AJ. Parental attendance at a school dental program: its impact upon the dental behaviour of the children. J School Health 1978; 48: 423. [ Links ]

6. Sheiham A. Promoting periodontal health-effective programmes of education and promotion. Int Dent J 1983; 33:187. [ Links ]

7. Schou L, Locker D. Oral health: a review of the effectiveness of health education and health promotion. Utrecht: Landelijk Centrum GVO; 1995. [ Links ]

8. Kay EJ, Locker D. Is dental health education effective? A systematic review of current evidence. Community Deni Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24: 231-235. [ Links ]

9. Kleemola-Kujala E, Räsänen L. Relationship of oral hygiene and sugar consumption to risk of caries in children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1982; 10: 224-233. [ Links ]

10. Axelsson P, Lindhe J, Nyström B. On the prevention of caries and periodontal disease. Results of a 15-year-longitudinal study in adults. J Clin Periodontol 1991; 13: 182-189. [ Links ]

11. Sgan-Cohen. Oral hygiene: past history and future recommendations. Int J Dent Hygiene 2005; 3: 54-58. [ Links ]

12. Lang NP, Attström R, Loë H. Proceedings of the European workshop on mechanical plaque control. Policy Statements. Berlin: Quintessence; 1998. p. 314. [ Links ]

13. Corchuelo J. Aplicación de estrategias para el monitoreo y control de placa bacteriana en escolares del Valle del Cauca. Cali: Artes Gráficas; 2004. [ Links ]

14. Ortiz L, Gutiérrez M, Moroni H, Medina K, Villavicencio J. Identificación del comportamiento de escolares y padres de familia respecto al mantenimiento de la salud oral. Odontol Sanmarquina 2009; 12(1): 13-17. [ Links ]

15. Góes L. Promoción de la salud, educación para la salud y comunicación social en salud: Especificidades, interfaces, intersecciones. Promotion & Education 2000; 7(4): 8-12. [ Links ]

16. Pilot T. Implications of the high risk strategy and of improved diagnostic methods for health screening and public health planning in periodontal diseases. In: Johnson NW, ed. Risk markers for oral diseases. Periodontal Disease 1991; 3: 441-453. [ Links ]

17. Sgan-Cohen HD, Kleinfeld Mansbach I, Haver D, Gofin R. Community-oriented oral health promotion for infants in Jerusalem: evaluation of a program trial. J Public Health Dent 2001; 61: 107-113. [ Links ]

18. Attina T, Horneckera E. Tooth brushing and oral health: how frequently and when should tooth brushing be performed? J Oral Health Prev Dent 2005; 3: 135-140. [ Links ] 19. Kemthong M, Vorawee L, Vittawat V, Attakorn C, Attakrit C, Weerapol B et al. Factors associated with parent capability on child's oral health care. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2012; 43(1): 249-255. [ Links ]

20. Corchuelo J. Sensitivity and specificity of an index of oral hygiene community use in relation to three indexes commonly used in measuring dental plaque. Colomb Med 2011, 42(4): 448-457. [ Links ]

text in

text in