1. INTRODUCTION

Lactic acid bacteria and several genera like Bacillus (1), Sporolactobacillus (2), Aeriscardovia, Alloscardovia, Bifidobacterium, Gardnerella, Metascardovia, Parascardovia and Scardovia (3), can produce lactic acid from fermentable sugars. Lactic acid bacteria have been used mainly to develop and preserve dairy products. This is the case with yogurt and cheese. In yogurt production, lactic acid fermentations provide texture, smell, and taste, and these fermentations are mainly carried out by bacteria that can transform lactose (4-5).

Lactic acid bacteria have been used to ferment different vegetal products, gluten-free and lactose- free. These food products are eating alternatives for people with celiac disease (6) or irritable bowel syndrome. For example, in Colombia, there is traditional fermentation of corn and/or rice doughs to produce bakery products (7). Oats and rice beverages fermentation have also been studied (8-11) as well as corn doughs (12).

There is a trend to add cereals or fruits to yogurt to increase dietary fiber content. Different kinds of prebiotics are used, such as fructans (inulin and fructooligosaccharides), galactans, and lactulose (13-14). The prebiotic effects are mainly related to the production of short-chain fatty acids that can reduce pathogenic microbiota and selectively stimulate the probiotic bacteria population by lowering intestinal pH (14).

Several technological aspects must be considered when incorporating probiotic microorganisms into a vegetable matrix. One of these aspects is the viability of the cells throughout the shelf life. The FDA (Food and Drug Administration) recommends that there must be a minimum count of 106 CFU*g-1 (Colony-Forming Unit) for the probiotic to present health benefits (15-16). Equally, the selection of the strain, the amount of inoculum to perform the fermentation, the physicochemical conditions of the substrate to inoculate the probiotics, the sensory characteristics of the expected product, the acceptability of consumers, the conditions of the processing, and the product storage must be considered (17).

Oat comprises 66.2 7% of carbohydrates, mainly starch, and only 1 % corresponds to sugars and oligosaccharides. In addition, it has 16.89 % protein, 6.90 % lipid, 9.7 % crude fiber, 8.22 % moisture, and 1.72 % ash (18). The Andean tubers and roots: The Andean oca (Oxalis tuberosa), ulluco (Ullucus tuberosus), yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius), arracacha ( Arracacia xanthorrhiza), mashua (Tropaeolum tuberosum) and turnip (Brassica rapa) have great nutritional benefits. However, nowadays, these tubers are unknown to most people, and they present low consumption related to low sensory acceptance, lack of diversification of gastronomic preparations and these tubers are unknown to most people (19-20).

The mashua is a tuber with high content of protein, carbohydrates, fiber, ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), and calories. It contains a high concentration of glucosinolates that confers antibiotic, insecticidal, nematicide, anticarcinogenic, and diuretic properties (21). People consume this tuber mainly cooked and later stewed with onion, tomato, and sometimes milk, whey, cheese, or curd is also added (19,22). Incorporating mashua in other formulations could be an alternative to increase its consumption and recover its production levels (23). Therefore, this research aimed to evaluate the lactic fermentation in dairy and non- dairy beverages using two commercial starter cultures.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Substrates preparation

Three different fermentable substrates were prepared: a control substrate with whole cow milk (S1), a substrate from oats flake (Avena sativa) (S2), and a mixture of oats flake and mashua pulp (Tropaeolum tuberosum) (S3). The formulation is shown in Table 1, according to previous sensory acceptance (data non-published).

Table 1 Substrate formulations

| Ingredients | g / 100 g | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | S2 | S3 | |

| Milk | 95.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Sucrose | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Oats flakes | 0.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Water | 0.0 | 93.0 | 83.0 |

| Mashua pulp | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.00 |

Whole Ultra High Temperature (UHT) cowmilk was added with 5.0 % sucrose, pasteurized at 80 ºC for 20 minutes, then tempered at 42 ºC and followed by the addition of the inoculum. The S2 formulation was prepared and cooked for 30 min to 92 °C; then, the mixture was ground in a blender for 2 min, filtered, and warmed up to 42 °C. Finally, mashua was cleaned, chopped, and cooked for 40 min to 92 °C, then drained, and the pulp was obtained with a mortar. The S3 mixture was mixed and heated to 42 ºC.

2.2 Inoculum preparation

Two freeze-dried starter cultures of commercial probiotic microorganisms were used. The CHOOZIT® MY 800 starter culture (Danisco) containing Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Lactis, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, and YOMIX® 883 LYO 50 starter culture (Danisco) containing Streptococcus thermophilus Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus. 100 g of each substrate at 42 ºC were added with 0.5 g of the starter culture and mixed for 5 min, following the manufacturer’s instructions for use. The initial counts of lactic acid bacteria were not considered. This inoculum was added to the 1,100 g of the rest of the substrate, homogenized, and incubated at 42 ºC for 6 hours. Samples were taken at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours during the fermentation process.

2.3 Determination of proximal composition of substrates before of fermentation

Determinations: moisture by the gravimetric method 930.15 (24), protein content by the Kjeldahl method 955.04 (24), fat content by method 920.39 (24), ash content by method 942.05 (24), total dietary fiber content by method 992.16 (24) and total carbohydrate content by difference method. The analyzes were carried out in triplicate.

2.4 Monitoring of pH, titratable acidity, and total soluble solids

5.0 g of each fermented product was weighed into a beaker, homogenized in 100 mL of distilled water, and pH was measured (HANNA, Colombia); subsequently, the mixture was titrated with 0.1 N NaOH until pH 8.3. The titratable acidity was expressed as a percentage of lactic acid and determined with equation (1).

Total soluble solids, Brix degrees, were determined with a digital refractometer (HANNA, Colombia). The refractometer was calibrated with distilled water. Titratable acidity, pH, and Brix degrees were conducted after 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 hours of the fermentation time. The analyzes were carried out in triplicate.

2.5 Lactic acid bacteria count

Lactic acid bacteria counts were carried out following the method 966.23-C (25). Briefly, samples of 10 g of were homogenized in 90 mL of 0.1% peptone water, pH 7.3 at 25 ºC. Dilutions were prepared to 10-7, and 1 mL of each dilution was seeded in triplicate in Plate Count Agar culture medium by the standard method. They were incubated at 30 ºC for 48 hours, and the lactic acid bacteria count was performed. The analyzes were carried out in triplicate.

2.6 Sensory analysis

Identification and selection of sensory descriptors for fermented beverages were carried out according to NTC 3932 (26). Then, a descriptive analysis of the color, smell, taste, and texture of each fermented product was performed after 6 hours of fermentation. 15 g of each sample were served in transparent plastic cups at an approximate temperature of 4 °C. The glasses were labeled with a random three-digit code and were arranged to be presented to the panelists sequentially and in random order. The analysis was carried out by ten trained panelists in food sensory evaluation of the gastronomy program of the Agustiniana University in Bogotá, Colombia.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Proximal analysis

Concerning the proximal composition of each substrate, protein content was higher for S1, and no significant differences were recorded between substrates S2 and S3. However, vegetables contribute a significant portion of total dietary fiber to the final product, but fermented dairy foods have better protein levels than non-dairy products (Table 2). Oat is one of the foods that provide the most dietary fiber; it can reach up to 13 g in a 100 g serving (10). Traditional yogurts do not have dietary fiber (27); therefore, enrichment or total substitution of milk with sources of dietary fiber like cereals could be an alternative to improve the functionality of this type of food.

Table 2 Proximal composition of fermented substrates

| Parameter | Whole cowmilk (S1) | Oats (S2) | Oats+Mashua pulp (S3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (%) | 3.36a | 1.22 ± 0.12b | 1.22 ± 0.22b |

| Fat (%) | 0.5a | 1.59 ± 0.10b | 1.39 ± 0.06b |

| Total dietary Fiber (%) | 0.0 a | 1.72 ± 0.003b | 0.06 ± 0.01a |

| Ashes (%) | 0.72 a | 0.17 ± 0.02 b | 0.19 ± 0.01 b |

| Moisture (%) | 80.76a | 87.43 ± 0.05b | 88.26 ± 0.02b |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 14.66a | 7.87 ± 0.25b | 8.88 ± 0.20b |

Same letters in the same row means no significant differences p<0.05.

Dietary fiber is an indigestible carbohydrate present in the edible parts of plants or fruits. Oats are one of the cereals highlighted by their great contribution of dietary fiber compared to other cereals such as rice, wheat, barley, or rye (28). In contrast, mashua is a tuber rich in starch (12.85%) and with a low content of dietary fiber (0.76%) (29). Therefore, substrate S3, prepared with a mixture of oats and mashua pulp, presented a lower dietary fiber content (0.06%) than the substrate S2 formulated with oats (1.72%). Fermented oats products present higher viscosity and help improve the intestinal microbiota; meanwhile the addition of mashua pulp enhances the contribution of antioxidant compounds such as betalains in the acid form of betaxanthins and betacyanins, as well as the supply of total dietary fiber (30).

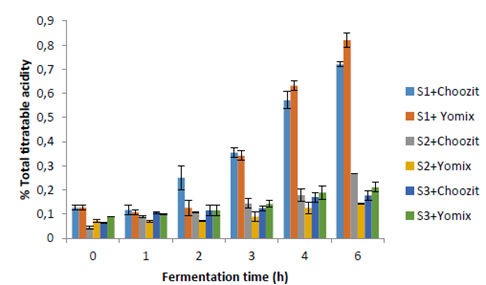

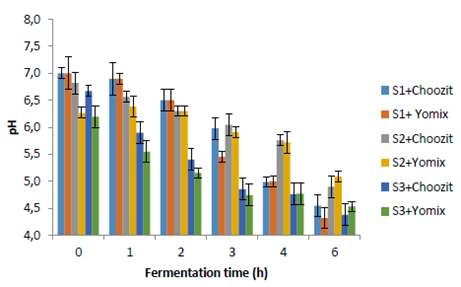

3.2 Monitoring of titratable acidity, pH and total soluble solids

The titratable acidity and pH values (Figures 1 and 2) show that a fermentation process occurred in different substrates using two starter cultures (Choozit and Yomix). Although the microorganisms present in the cultures are generally used for the fermentation of lactose, microorganisms could be adapted and were able to use other carbohydrates present in substrates (mainly starch) to start fermentation (27). This fact could be seen in S2 and S3. Fermentation was faster for S1. There are no significant differences in the process of S2 and S3 in terms of increasing acidity and decreasing pH. In studies carried out by Quicazán et al. (31) and Cuenca et al. (27), lactic acid fermentation of a non-dairy soy beverage was successful with 7 hours of incubation. In comparison, other fermented soy beverages with the addition of inulin have required up to 24 hours to reach adequate acidity levels (pH = 4.0 - 4.5) (4, 32).

It was reported that during the lactic fermentation of vegetable matrices (fruits and vegetables) (33), there is a drop in pH, an increase in titratable acidity, lactic acid bacteria growth, and a low decrease in total soluble solids.

Figure 1 Total titratable acidity is expressed as the percentage of lactic acid during fermentation time. S1 (whole cow milk), S2 (oats flakes), and S3 (mixture of oats flakes and mashua pulp).

Figure 2 pH during fermentation time. S1 (whole cow milk), S2 (oats flakes) and S3 (mixture of oats flakes and mashua pulp).

S1 could reach minimum pH between 4.0 and 4.5 (Figure 2). Contrary to that was found for S2 and S3. Although a decrease in pH was registered, it did not reach the minimum expected value, indicating that a longer fermentation time was required for non-dairy substrates of oats flakes and mashua pulp (4,32).

Fermentation behavior could be affected by the type of initial fermentable sugars and the amount of protein present in the substrates (Figure 3) and not by the initial total soluble solids. S1 registered initial values of 14 ºBrix and 3.36 % protein, while S2 and S3 started with 8.0 ºBrix and 1.22 % protein. Lactic acid bacteria are nutritionally demanding microorganisms that require certain concentrations of specific amino acids. Therefore, they depend on the production of peptidase proteinases and amino acid and peptide transport systems (34). Studies carried out by (31), in fermented soy beverages did not find significant differences in the appearance of lactic acid when the initial total soluble solids are more than 6.5 ºBrix.

3.3 Lactic acid bacteria count

In all substrates, there was survival of the probiotic microorganisms. However, the substrates inoculated with Yomix starter culture presented the highest lactic acid bacteria content (Table 3). Choozit® starter culture did not show good results for fermentation of lactose-free substrates such as S2 and S3 because the counts did not reach the 106 CFU*g-1 necessary for the fermented food to be considered probiotic (35). Apparently, microorganisms Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Lactis, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus included in the Choozit culture showed greater adaptation in the presence of milk lactose than oat starch and mashua of substrates S2 and S3. Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus presents of the Yomix culture does not exclusively ferment lactose, it would be suitable for vegetable substrates; contrary, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis with the enzyme β-galactosidase only reacts in the presence of lactose (36). However, the available starches in the substrates could influence the survival of the microorganisms. Oat flakes have higher starch content (4.32 %) (37) than mashua (1.9 %) (29), the initial physicochemical conditions of the substrate, the initial concentration of microorganisms. and the type of fermentable sugars influence the adaptation phase of lactic acid bacteria during the fermentation of non-dairy substrates (33).

Table 3 Count of viable lactic acid bacteria in fermented products after 6 hours incubation at 42ºC (CFU*g-1)

| S1+ CHOOZIT | S1 + Yomix | S2 + CHOOZIT | S2 + Yomix | S3 + CHOOZIT | S3 + Yomix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.99±0.64 x107a | 1.32±0.16 x109b | 5.13±0.31x102c | 1.09±0.03 x 109b | 1.82±0.57x102c | 1.82±0.57x109c |

S1 (whole cowmilk), S2 (oats flakes) and S3 (mixture of oats flakes and mashua pulp). Same letters in the same row means no significant differences p<0.05

3.4 Sensory analysis

Sensory characteristics of S1 were close to those described for yogurts; a higher acidity was perceived both in the smell and in the taste with Yomix starter culture (Table 4). It was not possible to show differences in the texture characteristics for the same substrates, but oats flakes have brought a slimy perception. Acidity during fermentation caused a color change from purple to lilac in the substrates containing mashua pulp. In a study carried out by (38) on yogurt with the addition of quinoa flour, the panelists described the product as a bright natural color, with a separation phase and acid aromas characteristic of high-intensity fermented foods with a creamy consistency. Meanwhile, Quicazán et al. (39) concluded that adding oatmeal to non-dairy yogurts diminishes raw vegetable flavors and improves sensory acceptability. During the fermentation process of sugars in vegetable substrates, some acidic lactic aromas develop, and the carbohydrates provided by oats have a high capacity to form gels, which increases the product viscosity allowing to obtain sensory characteristics similar to traditional yogurts (39).

Table 4 Sensory description of fermented products

| Experiments | Parameter | Sensory description |

|---|---|---|

| S1 + Choozit | Taste | Slightly sour, characteristic of yogurt |

| Smell | Acid milk, plain yogurt, slightly sour | |

| Color | White with creamy notes characteristic of milk | |

| Texture | Viscous, thick, dense, smooth on the palate | |

| S1 + Yomix | Taste | Sour, characteristic of yogurt |

| Smell | Sour milk, non-fruity yogurt, sour | |

| Color | White with creamy notes characteristic of milk | |

| Texture | Slimy, thick, creamy | |

| S3 + Choozit | Taste | Cooked oatmeal, slightly sour and tasteless |

| Smell | Cooked oatmeal, slightly sour | |

| Color | Cream white color | |

| Texture | Viscous, gelatinous, presence of small lumps | |

| S3 + Yomix | Taste | Cooked oatmeal, slightly sour and tasteless |

| Smell | Cooked oatmeal, slightly sour | |

| Color | Cream white color | |

| Texture | Viscous, gelatinous, presence of small lumps | |

| S2 + Choozit | Taste | Slightly sour, taste of cooked mashua, tasteless |

| Smell | Characteristic of cooked mashua | |

| Color | Intense lilac, purple | |

| Texture | Viscous, gelatinous, presence of fibers | |

| S2 + Yomix | Taste | Sour, cooked mashua flavor, tasteless, astringent |

| Smell | Characteristic of cooked mashua and slightly sour | |

| Color | Intense lilac, purple | |

| Texture | Viscous, gelatinous, presence of fibers |

CONCLUSIONS

Lactose-free fermented yogurt-like products can be made from oats flakes or a mixture of oats flakes and mashua pulp. However, a fermentation process of more than 6 hours required higher initial soluble solids. The bacteria Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus contained in the Yomix starter culture showed the greatest adaptation to the lactose-free substrates compared to the interaction of Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Lactis, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus, of the Choozit starter culture. Bacterium Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Lactis is highly dependent on lactose content to survive.

The substrate made only with oats presented the best physicochemical characteristics of fermentation and sensory characteristics of flavor and texture. The substrate with mashua showed an astringent taste and the presence of fibers, although the increase in acidity during fermentation improved the intensity and brightness of the lilac color.