In the beginning of the health emergency caused by the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, millions of workers experienced abrupt changes in their work dynamics, affecting the way they interact with the job (McDowell et al., 2020; Vyas & Butakheio, 2021). In addition to the possible negative consequences this health emergency could have on workers’ material and economic conditions (United Nations (UN), 2020), the way and the degree to which they feel satisfied with their jobs could also be affected. In this sense, previous studies on workers immersed in challenging environments or emergency contexts show that workers feel significantly less satisfied with their jobs, especially when they perceive a direct threat to their physical or mental health (Ali Jadoo et al., 2018; Thielmann et al., 2022).

For decades, research on work has been interested in exploring individuals’ emotional, cognitive, and behavioural reactions to their jobs, trying to identify and evaluate ways these experiences affect, positively or negatively, the professional life of employees (Dalal, 2013; Diakos et al., 2023). As a result, several constructs have been developed and validated, and job satisfaction (JS) is one of the most important aspects to understand in the interaction between people, the working world, the psychological, and the emotional, environmental, and social factors affecting this interaction (Judge et al., 2017). Thus, as job satisfaction is a multidimensional measure reflecting individuals’ affective experiences, beliefs, and evaluative judgments about work (Lepold et al., 2018), it plays a significant role both in the work dynamics of organisations and in the health and well-being of workers (Hansson et al., 2022; Montuori et al., 2022). In general, JS has been measured using multiple-item (MI) and single-item (SI) measures. Although MI has greater theoretical advantages, several studies have indicated that the use of SI measures is also methodologically and analytically suitable for investigating JS-related outcomes (Fakunmoju, 2020; Poetz & Volmer, 2022).

Although the centre of the meaning of job satisfaction is cognitions (subjective judgments), affects also play an important role in the extent to which people value their work (Schlett & Ziegler, 2014). Affects are a range of temporary subjective experiences, associated with emotions or moods and can be of positive or negative valence (Lyubomirsky et al, 2005). Thus, when affects are positive (PA) pleasure is experienced and this includes emotions such as enthusiasm, inspiration, or determination, while when they are negative (NA) they are associated with feelings of discomfort and include emotions such as fear, nervousness, or anguish (Barrett & Bliss, 2009). The literature on how the balance of PA and NA relates to JS still presents some challenges, due to the scarcity of research and the lack of a unified theoretical framework to explain these results (Yoon et al., 2021). Therefore, to contribute empirically and theoretically to research on the balance of affect and its relationship with JS, the broaden-and-build (Fredrickson, 2001) and affective circumplex (Posner et al., 2005) theories were integrated to understand how the interaction of PA and NA during adverse events can influence workers’ JS levels.

According to the broaden-and-build theory, affective and negative experiences play a different role in peoples’ lives. PA builds personal resources that have a lasting impact on well-being, increasing the likelihood of people feeling good and satisfied in the future, while NA promotes quick and specific actions seeking an immediate and direct benefit (Fredrickson, 2001). In turn, the affective circumplex theory describes the bipolar structure of affective states, based on two dimensions (arousal, ranging from high to low activation, and hedonic valence, ranging from pleasant to unpleasant states), both strongly related but independent of each other (Posner et al., 2005). In this sense, affective feelings can occur simultaneously, i.e., a person can experience positive and negative affects at the same time (Barrett & Bliss, 2009). Thus, it has been shown a general balance of PA and NA can predict subjective experiences such as well-being and satisfaction (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018). Based on these theoretical perspectives, applying the cluster analysis method allows for a more refined approach to the interaction of PA and NA levels and how this combination could be related to workers’ JS.

In the literature, some evidence showed the effect of the balance between PA and NA on job satisfaction. According to these findings, the more active, energetic, interested, and less distressed, scared, or nervous people feel about their jobs, the higher are the levels of job satisfaction they generally perceive (Jasiński & Derbis, 2023; Nikolaev et al., 2020; Sang et al., 2019). Furthermore, it was reported that people who manage to change their negative affections for positive ones, through pleasant and positive experiences, improve their job evaluations, reflecting greater job satisfaction (Chuang et al., 2019; Fiori et al., 2015). In challenging environments, the subjective experience of affect works as an adaptation strategy in the face of external demands and life opportunities. In this sense, evidence shows that, in work contexts, people who experience more positive than negative affect feel more satisfied with their jobs, which, in turn, improves their predisposition to adapt to change in environments demanding great flexibility, dynamism and rapid change (Fiori et al., 2015; Gori et al., 2020).

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, the growing threat of infection has generated a significant increase in psychological distress and anguish symptoms in workers (Wang et al., 2021). Thus, the aim of this study was to explore levels of job satisfaction in a group of workers regarding positive and negative affects during the COVID-19 health emergency. Furthermore, in the present study, the hypotheses below are tested in line with previous literature: Hypothesis 1a. Positive affects are positively related to job satisfaction; Hypothesis 1b. Negative affects are negatively related to job satisfaction; Hypothesis 2. Considering the interaction between PA and NA valences associated with JS, the conglomerates will be grouped as follows: a. High PA, high NA and high JS; b. High PA, low NA and high JS; c. Low PA, high NA and low JS; d. Low PA, low NA and low JS.

Method

Participants

The sample included 594 workers of both sexes from Brazil (n = 306), Colombia (n = 165) and Chile (n = 123). The snowball technique was used to recruit participants. This is a non-probability sampling method that identifies key people to contact other people who could provide data of interest. This process was facilitated by researchers linked to the study, who invited potential participants via virtual environments. From the total list of interviewees, those who reported having a job, being over 18 years old and voluntarily agreeing to take part in the study were considered.

Instruments

PANAS Scale - Short version. Emotional well-being was assessed in terms of the level of intensity experienced in Positive Affects (PA) and Negative Affects (NA) using the short version of the PANAS scale (Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS was originally a self-report scale based on two subscales: the first measured PA and the second measured NA, each with 10 items respectively. The shortened version adapted for this study included 5 items to assess PA (e.g., “Interested” and “Active”) and 5 items to assess NA (e.g., “Nervous” and “ Afraid”). The items are composed of adjectives with an answer key in the form of a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “Not at all” to 5 “Extremely”. The total score for each subscale is taken from the sum of the items composing each construct, with higher scores being interpreted as a greater presence of affection. The PANAS has been adapted in different Latin American samples and showed adequate validity indices (PA: a = 0.779 and w = 0 .781; N A: a = 0.812, w = 0.813) with no significant differences between subsamples (Feld’s W: PA = 6 .99, N A = 6 .65; gl = 3; p < 0.01) (Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2020). In this study, the parts of PA and NA of PANAS in its adapted version presented an acceptable internal consistency in the general sample (PA: a = 0.847, 95% CI: 0.827 - 0.866; NA: a = 0.884, 95% CI: 0.869-0.899).

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured by means of the item: “I am satisfied with the work activities I am carrying out”. The answer options are based on a Likert scale format from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating greater job satisfaction (1 = “Totally false”, 2 = “False, in most cases”, 3 = “Neutral”, 4 = “True, most of the time” and 5 = “Totally true”). This item is part of a 31-question survey designed and applied for general study.

Procedure

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Institute of the Federal University of Pará, Brazil (code number: CAAE: 30365720.8.0000.0008), and is part of an international study entitled “Psychological effects of social isolation in the coronavirus pandemic”, carried out between March and April 2020. A virtual survey composed of 65 questions was designed and applied using the SurveyMonkey virtual platform. The sample selection process was facilitated by the researchers in each country and conducted by means of a virtual environment (social networks and email addresses). Participants took between 10 and 15 minutes to answer the proposed questions and the collected information was stored in a general database. The final list of this general sample was composed of 5,499 people, and a representative sample was taken from the Latin American countries with the highest number of responses. After eliminating participants with missing or incomplete data, the final sample for this study was 594 workers. Finally, data was tabulated and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 26 IBM software. License - Series: 10101181019).

Statistical analysis

To analyse the data, cluster analysis was applied to group the sample cases into homogeneous and hierarchically classified groups (Zhang et al., 2017). A two-phase process was employed: in the first phase, Ward’s hierarchical minimum variance cluster analysis was carried out to determine the number of clusters in an exploratory manner. In the second phase, K-Medias cluster analysis was conducted using the number of clusters identified by Ward’s method. The ANOVA test was used for cluster validation, since it is one of the strongest tests for accurately validating cluster grouping (Dunn et al., 2018). Post hoc multiple comparisons were performed using the Turkey-Kramer method or the Tamhane method (if the variations were not homogeneous). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

The sample included 594 workers surveyed online in three different countries: Brazil (n = 306), Chile (n = 123) and Colombia (n = 165). The gender distribution was mainly composed of women (70%), with an overall average age of 38.01 years (SD = 10.479). 82.5% of the participants had a family structure of between two and five people, and 42.1% reported having a family income of more than US$1,200.00. During the quarantine proposed by governments, 68% of the participants reported isolating themselves at home to prevent spreading COVID-19. Similarly, 67.3% of the participants reported isolating themselves preventively for 15 days or more. Similar to existing evidence, positive affect (M = 15.32, SD = 4.045) and negative affect (M = 13.35, SD = 4.803) were significantly correlated with job satisfaction (r = 0.403, p < 0.01 and r = -.265, p < 0.01, respectively).

Cluster analysis

In the Ward hierarchical group analysis and K-means analysis, four groups of workers were identified using input variables: negative affects, positive affects, and job satisfaction. To detect the number of groups, the cluster grouping graph (Dendogram) of Ward’s group analysis method was used. In this study, four groups were formed (see figure 1) when increasing heterogeneity was used as a determining factor.

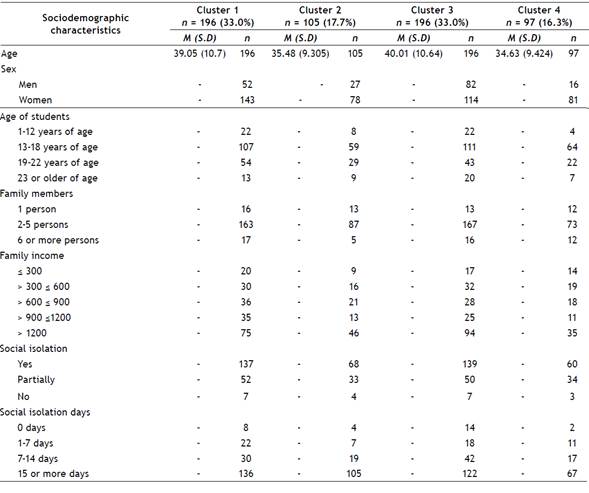

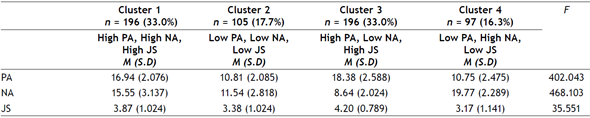

Four clusters were identified with statistically different and discriminating measures of positive affect (F = 402,043, p = 0 .000), n egative a ffect ( F = 468.103, p = 0.000) and job satisfaction (F = 35.551, p = 0.000) scores (see Table 1). Thus, group 1 (33.0%) was characterised by presenting high levels of positive affects (M = 16.94; SD = 2.076), high levels of negative affects (M = 15.55; SD = 3.137) and moderate job satisfaction (M = 3.87; SD = 1.024). Group 2 (17.7%) included workers with low levels of positive affects (M = 10.81; SD = 2.085), low levels of negative affects (M = 11.54; SD = 2,818) and moderate job satisfaction (M = 3.38; SD = 1.024). In group three (33.0%), high levels of positive affects (M = 18.38; SD = 2,085), low levels of negative affects (M = 8.64; SD = 2,024) and high job satisfaction were found. (M = 4.20; SD = 0.789). Finally, group 4 (16.3%) is characterised by low levels of positive affects (M = 10.75; SD = 2.475), high levels of negative affects (M = 19.77; SD = 2.289) and low satisfaction (M = 3.17; SD = 1.141) (see Table 1). The sociodemographic characteristics of the four groups (n = 594) are available on Table 2.

Table 1 Measures of positive affect, negative affect and job satisfaction in the 4 groups

Note. PA = Positive Affect; NA = Negative Affect; JS = Job Satisfaction.

Cluster 1. Workers with high levels of positive affect, high levels of negative affect and moderate job satisfaction

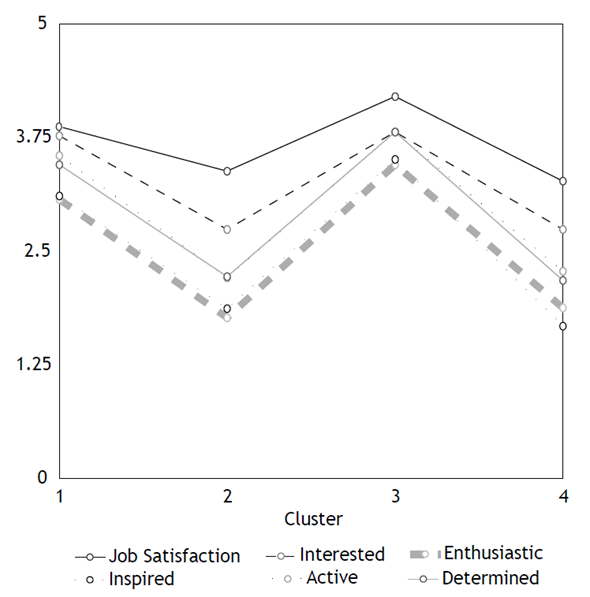

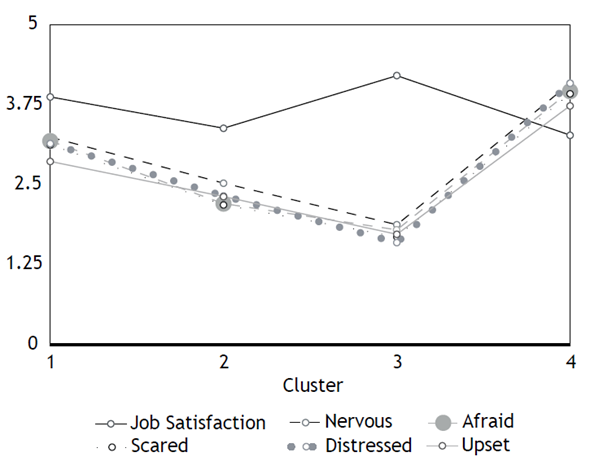

Group 1 (n = 196; 33%) was one of the largest and included workers with high scores in positive affects (M = 16.94; SD = 2 .076), n egative a ffects (M = 15.55; SD = 3.137) and moderate scores in job satisfaction (M = 3.87; SD = 1.024); this is slightly above the total average for the overall sample. This group was moderately satisfied with their work activities and the results indicated that they experienced intense affects. Positive affects expressed as “Interested” (M = 3.77; SD = 0.720) and “Active” (M = 3.55; SD = 0.725) and negative affects expressed as “Nervous” (M = 3.24; SD = 0.889) and “Afraid” (M = 3.18; SD = 0.863). All the averages were slightly above the general average (see figure 2).

Cluster 2. Workers with low levels of positive affect, low levels of negative affect and moderate job satisfaction

The workers in this group (n = 105; 17.7%) reported low scores for positive affects (M = 10.81; SD = 2.085), low scores for negative affects (M = 11.54; SD = 2.818) and moderate job satisfaction (M = 3.38; SD = 1.069), slightly below the general average. As a whole, workers in this group indicated a low intensity of positive affects. “Enthusiastic” (M = 1.77; SD = 0.883) and “Inspired” (M = 1.87; SD = 0.760) are the most representative choices. Similarly, this group reported low levels of negative affects, with “Nervous” (M = 2.52; SD = 0.878) and “Distressed” (M = 2.32; SD = 0.956) being the most significant. The averages were slightly below the general average (see figure 3).

Cluster 3. Workers with high levels of positive affect, low levels of negative affect and high job satisfaction

This was another large group (n = 196; 33%) and reported high positive affect scores (M = 18.38; SD = 2.588), low negative affect scores (M = 8.64; SD = 2.024) and high job satisfaction scores, significantly above the standard average of the general population (M = 3.79; SD = 1.045). Thus, this group of workers was characterised as more satisfied with their work than other groups and experiencing more positive than negative affects. Among the positive affects, the most representative were “Interested” (M = 3.81; SD = 0.753), “Active” (M = 3.81; SD = 0.753) and “Determined” (M = 3.81; SD = 0.725) which were significantly above the total average. At the same time, they reported experiencing fewer negative affects. “Scared” (M = 1.68; SD = 0.644) and “Distressed” (M = 1.59; SD = 0.614) were the most prominent of these and significantly below of the total average (see figure 1).

Cluster 4. Workers with low levels of positive affect, high levels of negative affect and low job satisfaction

In contrast to other groups, this one (n = 97; 16.3%) was the smallest and consisted of workers with low positive affect scores (M = 10.75; SD = 2 .475), h igh n egative a ffect scores (M = 19.77; SD = 2.289) and low job satisfaction sco-res (M = 3.27; SD = 1.141). Slightly below the general population average. This group of workers reported low job satisfaction and indicated experiencing more negative affect: “Nervous” (M = 4.08; SD = 0.745) and “Distressed” (M = 4.08; SD = 0.672) were the most representative choices and much higher than the total sample average. Similarly, in relation to positive affects, workers reported feeling less “Inspired” (M = 1.68; SD = 0.730) and “Enthusiastic” (M = 1.88; SD = 0.767), i.e., far from the total average (see figure 3).

Discussion

The present study adds to an extensive literature on JS and affects. Despite this large body of evidence, these findings represent the first attempt to identify, by way of cluster analysis, the ways in which PA, NA, and JS interact in statistically differentiated homogeneous groups. Test of hypothesis 1a and hypothesis 1b were supported by the results, indicating that JS correlates positively with PA and negatively with NA. Taken together, these results sugg-est that people who experience high PA are more satisfied with their work, which is consistent with the broaden-and-build theory by confirming that the higher the PA, the better the satisfaction and well-being outcomes (Fredrickson, 2001). On the other hand, these results highlight that the interaction of PA including high NA, mentions high levels of JS, which also agrees with the assumption of the affective circumplex theory regarding the simultaneous interaction of affects and their effects on people’s lives (Posner et al., 2005).

In the cluster analysis, 4 homogeneous groups were identified in relation to JS, PA, and NA levels in a cohort of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Group 1 (n = 196, 33%) was characterised by high levels of JS and high levels of PA and NA. Group 2 (n = 105, 17.7%) presented low levels of JS and low levels of PA and NA. In contrast, group 3 (n = 196, 33%) was characterised by high levels of JS, high levels of PA, and low levels of NA. Finally, group 4 (n = 97, 16.3%) reported low levels of JS, high levels of NA and low levels of PA. Supporting hypothesis 2, this classification supports the results of some evidence showing that different forms of interaction between PA and NA are related to workers’ levels of job satisfaction (Dewi et al., 2014; Lan et al., 2022).

In the results of groups 1 and 2, participants reported congruent valences of PA and NA. Thus, workers who showed a high valence of PA and NA (cluster 1) presented high job satisfaction scores, while those who showed a low valence of PA and NA reported lower job satisfaction scores (cluster 2). In situations where high PA and NA are congruent, it has been suggested that PA tends to be dominant when judging job satisfaction (Lan et al., 2022). Furthermore, this dominance of PA would help to promote the ability to regulate and control emotions and mood, which could attenuate the effect of NA and increase levels of job satisfaction (Kafetsios & Zampetakis, 2008; Madrid et al., 2020).

On the other hand, in situations where low PA and NA are congruent (Cluster 2), contrary to the results, some evidence has suggested that low levels of PA and NA do not always lead workers to low levels of job satisfaction (Dewi et al., 2014; Lan et al., 2022). According to the evidence, high affect valences lead to greater activation (Hoyt et al., 2015), which leads people to better environment appraisals and more adaptive behaviours when related to PA or more judgments and negative and inhibitory behaviours when related to NA (Clore et al., 2018). In work environments, this factor could contribute to the extent that people feel more satisfied or dissatisfied with their work. Based on this reasoning, a possible explanation for this result is that experiences with low levels of NA or PA could lead to less activation, which, in turn, would inhibit the making of judgments or evaluations, whether positive or negative about work.

Distinct from groups 1 and 2, the results found in clusters 3 and 4 showed workers who experienced high PA with low NA (cluster 3) and low PA with high NA (Cluster 4) with high and low levels job satisfaction, respectively. Specifically, these findings show that in situations where the valence of PA and NA is incongruent, the effect on job satisfaction could depend on the type of affect whose valence is higher. According to the literature, when individuals experience higher levels of PA than NA, PA promotes dominant cognitive responses in relation to object, while higher levels of NA than PA inhibit these responses (Clore et al., 2018; Isbell et al., 2016). Thus, based on this idea, the subjective judgments and evaluations reported by people concerning general aspects of the job could be negatively or positively influenced when the object evaluated was related to high levels of PA or NA, respectively.

Besides describing how affections are homogeneously grouped in relation to JS, these results are relevant due to the COVID-19 pandemic in working life. During times with these challenging conditions, encouraging discussion on the results of groups 1 and 3 could contribute towards the way workers cope with these demands. As has been suggested, the subjective experience of positive affect leads people to feel more satisfied with their work, which improves their ability to adapt to change in the face of adverse and demanding situations (Buonomo et al., 2020; Forjan et al., 2020). Conversely, although the threat of COVID-19 infection has had a negative impact on people’s lives (Lima et al., 2020), the results for groups 2 and 4 need to be expanded in order to understand how negative affect, related to job dissatisfaction, could intensify the discomfort generated by the pandemic.

The results of this study have some practical implications. Firstly, they can be used simply to assume that certain levels of positive and negative affect can occur with certain levels of job satisfaction. These findings facilitate an understanding of how the interaction between PA and NA can influence JS. Although stimulating high levels of positive affect is ideal for increasing employee satisfaction, it is also advisable for human resource managers to help their employees in managing and balancing positive and negative affect. One way to induce positive affect is to create a work environment that promotes positive and favourable experiences. According to some authors, certain actions are recommended: establishing positive relationships, improving the physical environment, creating a reward system or encouraging workers’ participation in the organisation’s decision-making process (Bouckenooghe et al., 2013; Koo et al., 2020).

On the other hand, during periods of crisis or adversity with higher rates of negative affect and lower satisfaction, human resource management can train their employees to deal with the stress and anguish caused by these events. For example, it is advisable for organisations to implement intervention programmes regarding emotional regulation skills, in which workers are encouraged to accept, tolerate, and modify negative affects (Buruck et al., 2016). Mindfulness training also needs to be encouraged so that employees can alleviate the negative effect of stressful events and improve their sense of well-being and job satisfaction (Lin et al., 2020; Menardo et al., 2022).

This study has some strengths and limitations that may direct future research. Since the study of affect balance in relation to JS still presents large knowledge gaps, this study represents an important empirical advance presenting important results regarding the combination of PA and NA and their influence on JS. Although a robust tool was used, hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA), studies using other techniques such as latent class analysis (LCA) are highly recommended, since they allow a more theoretical analysis of the results. However, in contexts where the theoretical model is unclear, the application of HCA and LCA is very useful because it enables a search convergence in the results (Ondé Pérez & Alvarado Izquierdo, 2019). Moreover, these results should be considered through their limitations, which highlight future research. This study offers a cross-sectional data analysis, making it impossible to know whether the identified groups are sustained over time. Longitudinal studies that can prospectively analyse the stability of PA and NA and their predictive capacity for JS are therefore recommended.

Conclusions

In this study, the subjective experience of affect in relation to levels of JS showed that different combinations of levels between PA and NA, associated with JS, were grouped together in statistically homogeneous groups of a cohort of workers. In groups where PA was high, even when NA was high, people felt more satisfied with their jobs. On the other hand, in the groups where NA was high or low, together with low PA, people felt more dissatisfied with their jobs. We suggest that the classification found in this study be validated longitudinally to expand knowledge on the ways affect and work interact1 2.