Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Cuadernos de Economía

Print version ISSN 0121-4772On-line version ISSN 2248-4337

Cuad. Econ. vol.28 no.50 Bogotá Jan./June 2009

HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: A NON-COMPENSATORY ASSESSMENT

Sebastián Lozano Segura*

Ester Gutiérrez Moya

* PhD. in Industrial Engineering, University of Seville, Spain. Degree in Industrial Engineering from the University of Seville, Spain. Professor of Quantitative Methods in Management in the Department of Management at the University of Seville, Spain. E-mail: slozano@us.es. Address: Camino de los Descubrimientos s/n, 41092-Seville (Spain).

PhD. in Economics, University of Seville, Spain. Master Science in Statistics, University of Seville, Spain. Degree in Business Management and Administration, University of Seville, Spain. Degree in Statistics, University of Seville, Spain. Associate professor in the Department of Management at University of Seville, Spain. E.mail: egm@esi.us.es. Address: Camino de los Descubrimientos s/n, 41092-Seville (Spain).

This article was received on April 22, 2008 and his publication approved on April 17, 2009.

Resumen

El Índice de Desarrollo Humano es un indicador sintético basado en tres dimensiones esenciales: longevidad, educación y nivel de vida. En este trabajo se adopta una perspectiva no-compensatoria que considera que la privación de cualquiera de estas dimensiones básicas no puede ser suplida por los logros en otra. Según este punto de vista, se propone utilizar el mínimo de los componentes, en lugar de la media aritmética. En el documento se presentan los resultados de esta nueva evaluación para los últimos cinco años del índice H D I. Este nuevo indicador (N C H D I), a pesar de estar correlacionado con el H D I, proporciona una ordenación diferente de los países, nuevos conocimientos sobre los desequilibrios presentes en el H D I, y puede ser utilizado a nivel nacional y local.

Palabras clave: Índice de Desarrollo Humano, no compensatorio, desarrollo desequilibrado. JEL: O15, C61.

Abstract

The Human Development Index is a summary measure of Human Development on three basic dimensions: longevity, knowledge and standard of living. An index is computed for each of these three dimensions and a simple average computed. In this paper we adopt a Non-Compensatory perspective that considers that deprivation in any one of these basic dimensions cannot be compensated by achievements in any other. Consistent with this view, we propose to use the minimum of the component indeX Es instead of the arithmetic average. We present the results of this re-assessment of the H D I for the last five years’ data. Although correlated with the H D I, this N C H D I gives a different ranking of the countries and, above all, provides new insights into imbalances within the H D I. The new index can also be used at the national and local levels.

Key words: Human Development Index, Non-Compensatory, unbalanced development. JEL: O15, C61.

Résumé

EL’Indice de Développement Humain est un indicateur synthétique basé sur trois dimensions essentielles : longévité, éducation et niveau de vie. Dans ce travail on adopte une perspective non-compensatrice qui considère que la privation de n’importe laquelle de ces dimensions basiques ne peut pas être résolue par des réussites dans une autre. Selon ce point de vue, on se propose d’utiliser le mínimum des composants, au lieu de la moyenne arithmétique. Dans le document on présent les résultats de cette nouvelle évaluation pour les cinq dernières années de l’IDH. Le nouvel indicateur (N C H D I), bien qu’il soit relié à l’IDH, pourvoit un classement différent des pays, de nouvelles connaissances sur les déséquilibres présents dans l’IDH, et peut être utilisé à niveau national et local.

Mot clés: L’Index de Développement Humain, non-compensatoire, développement déséquilibré. JEL : O15, C61.

INTRODUCTION

In 1990, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) introduced the Human Development Index (H D I) as a summary measure of Human Development (H D) on three basic dimensions, namely longevity, knowledge and standard of living. An index is computed for each of these three dimensions and a simple average computed. Since its conception, the H D I has been the focus of a public debate. Apart from other criticism (e.g. Srinivasan 1994), some scholars have called it redundant in the sense that H D I is generally highly correlated with its component indeX Es (see e.g. McGillivray 1991, Srinivasan 1994 and Cahill 2005). Other researchers (e.g. Trabold-Nübler 1991, Lüchters and Menkhoff 1996) have shown some undesirable consequences of the way some components are derived, thus leading UNDP to refine the H D I along the years to correct those flaws. Morse (2003) presents a summary of the evolution in the calculation of the H D I. It is not the aim of this paper to discuss the choice of capabilities included in the H D I.

An important issue is that the aggregation of the component indices forces the specification of tradeoffs between the various H D I dimensions (Kelley 1991). The index allows attainments in any one of the three dimensions to be traded off against another (Ravallion 1997). In fact, the equal weighting of the component indeX Es suggests a perfect substitution between them and therefore implicit trade-offs between the corresponding dimensions (Desai 1991). He suggests the use of a log additive formula as a way of restricting substitutability. Along the same lines, Sagar and Najam (1998) propose a Reformed H D I that, instead of averaging the component indeX Es, multiplies them so that a high value of the H D I would require high values of the three component indeX Es simultaneously.

However, as recognized in Hopkins (1991) there is no a priori rationale that allows one to add life expectancy to literacy. Most researchers have however maintained the additivity of the component indices, including those such as the Modified H D I (Noorbakhsh 1998a) and the Rescaled New H D I (Mazumdar 2003) that use Euclidean vector distance. Not all approaches, however, have maintained the equal weighting of the components. Thus, Noorbakhsh (1998b) use weights derived from the data using Principal Component Analysis, while the Data Envelopment Analysis approach in Despotis (2005a, 2005b) and more recently Lozano and Gutiérrez (2008) determine different weights for each country so that it appears under the best possible light.

In this paper, we propose an explicit Non-Compensatory (NC) criterion that is based on the assumption that the achievements in one dimension cannot compensate an underachievement in another. In this way the simplicity of H D I of providing a single figure from a reduced number of component indicators is maintained. However, “the task of specification must relate to the underlying motivation of the eX Ercise as well as dealing with the social values involved” (Sen 1989). Thus, the philosophical principle emphasized in N C H D I is that of the inalienability of the inherent rights to human development in all its different dimensions. This concept is especially important since the measures of deprivation considered in H D I correspond to basic human needs that can foreclose many other capabilities. On the one hand, averaging, in a weighted or unweighted way, implies an implicit condoning of part of these deprivations, most importantly, those that are most acute. On the other hand, the non-compensatory principle is consistent with the non-commensurability of the diverse aspects of development. On these ethical and practical grounds is based our proposal for a non-compensatory assessment of the H D I.

Note that we are not rejecting the possibility or convenience of devising a composite, aggregate measure of human development. Our objections are against the usual ways of carrying out such aggregation.

The structure of this paper is the following. In section 2, after detailing the calculation of H D I, the N C H D I is introduced and discussed. Section 3 presents the results of the N C H D I vis-à-vis H D I for the data of the last five years. The last section summarizes and concludes.

NON-COMPENSATORY H D I

The three component indeX Es of the H D I (life expectancy index, education index and G D P per capita index) are computed based on four indicators:

- Life Expectancy at Birth (LEB) indicator, ranging from 25 to 85 years

- Adult Literacy Rate (ALR), ranging from 0 to 100

- Combined primary, secondary and tertiary Gross Enrolment Ratio (G E R ), ranging from 0 to 100

- Logarithm of the Gross Domestic Product (L G D P ) per capita in US Dollars purchasing power parity, ranging from log(U S D 100) to log(U S D 40000)

The corresponding Life Expectancy Index (X L E) is computed as:

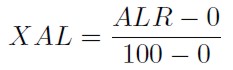

The Adult Literacy Index (X A L ), computed as:

is combined (with respective weights 2/3 and 1/3) with the corresponding Gross Enrolment Index (X G E ):

giving the Education Index (X E ):

Finally, the G D P per capita Index (X G D P):

allows the H D I to be computed as the simple average of the three component indices:

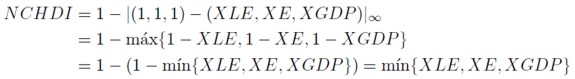

The NC approach we propose does not allow for any trade off (neither explicit nor implicit) between the different H D I dimensions. All of them are considered basic and inalienable. Neither adding nor multiplying the component indices nor any similar way of introducing compensatory effects between them is considered admissible. A suitable N C H D I index may be computed as the minimum of the component indices, i.e.

This index corresponds to one minus the Tchebycheff distance between the vector of component indices and the Ideal Point (1, 1, 1). This Ideal Point represents attaining the maximum values of the goalposts of the different H D I dimensions. The distance to such a reference point may represent a measure of the lack of attainment of these goals. But instead of using rectangular distance (a.k.a. l1 metric) as H D I does, or Euclidean distance (a.k.a. l2 metric) as the Modified H D I or Rescaled New H D I do, we propose using Tchebycheff distance (a.k.a. l∞ metric) which does not require additivity and is NC. The Tchebycheff distance between two vectors is equal to the maximum of the absolute value of the component-wise difference between both vectors. Thus,

This minimum criterion is used in Multiple Attribute Decision Making (e.g. Yoon and Hwang 1995, p. 28) and reflects a pessimistic evaluation approach that scores an alternative according to its worst performance among the different criteria. Similarly, N C H D I scores each country according to its lowest level of goal achievement. This way of assessing the H D I sends a clear signal to each country about where its priority should be. It also makes explicit that none of the H D I dimensions (a long and healthy life, knowledge and a decent standard of living) may be left behind. All of them are considered equally important and desirable. For those countries that have unbalanced component indices, the N C H D I provides anincentive to improve the lagging dimension. We consider this ability of N C H D I to identify the most largely unmet needs rather useful. In addition, N C H D I’s maximin structure is analogous, mutis mutandis, to the difference principle in Rawls’ Theory of Justice (Rawls 1971). Thus, the improvements in some dimensions of the H D I are not worth much if they are not accompanied by parallel improvements in the worst off dimensions. In other words, according to N C H D I, improving the most neglected dimension of human development has a higher priority than improving those better off. In this sense, it can be said that N C H D I implicitly establishes priorities but in a dynamic, non-parametric and socially just way.

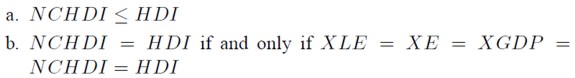

It is trivial to prove the following two properties:

Three additional considerations are in order. First, that the NC criterion has a clear drawback, which is that not all improvements in the component indices translate into improvements in the NC-H D I, i.e. it can happen that a country may improve one component while its NC-H D I may not improve. This happens whenever the lowest component index does not improve. Although this lack of monotonicity is an undesirable feature, it is unavoidable and intrinsic to its NC character.

The second remark is that N C H D I selects one of three component indices, discarding the other two. This is not equivalent to the approaches (such as Ogwang 1994, Ogwang and Abdou 2003) that propose to use just one of the component indices to compute the H D I. The difference lies in that which of the three components is selected is not fiX Ed but can change from one country to another.

Finally, the same as the H D I, the proposed N C H D I can be used not only at the national level but also at the regional or local level, thus helping to detect the specific and more urgent problems in each geographical area.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

The proposed N C H D I has been computed for the H D I 2000 through H D I 2004 contained in the Human Development Reports (H D R) of the latest five years (i.e. H D R 2002 through H D R 2006 respectively). Table 1 shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between N C H D I and H D I for the five years. It can be seen that there is a significantly strong but not perfect linear relationship between both indices. This can also be seen in Figure 1, which shows a scatter plot of H D I versus N C H D I for year 2004. The graphs for the other four years are similar and are not shown to save space. Note that, as expected, all points fall below the diagonal, which corresponds to N C H D I=H D I. The closer a point is to the diagonal, the more balanced are the corresponding H D I component indices and, on the contrary, the farther from the diagonal, the more unbalanced the H D I component indices. Figure 2 shows, for year 2004, the distribution of the difference between the maximum and the minimum H D I components as well as that of the difference between the average component index (i.e. the H D I) and the minimum component index (i.e. the N C H D I). Note that the imbalance in the H D I component indices can be important in some cases and that such imbalance is generally reflected in a larger H D I - N C H D I difference.

N C H D I highlights the need to improve in those H D I dimensions that fare worst for each country. H D I, on the contrary, can mask underperformance of a certain dimension with a good performance in another, thus in a certain sense hiding or de-emphasizing the problem. Take the case of Botswana, for example. In 2004, its H D I has been a low but seemingly “reasonable” value 0.570 that makes it in position 131 out of 177 in the H D I ranking. This relatively high H D I is the average of two high components X E = 0.777 and X G D P = 0.768 and a worrisomely low value X L E = 0.165. The latter is the one that N C H D I takes and corresponds to next to last position in N C H D I ranking. Our claim is that the relatively high G D P per capita and enrollment and literacy rates of Botswana cannot compensate its dramatic 34.9 years of Life Expectancy at Birth. This is why we believe that the proposed N C H D I is more valid the H D I, i.e. because it gives a clearer picture of the real situation of Human Development.

Since, as Booysen (2002) argues, composite indices such as the H D I have an ordinal nature (insofar as the magnitude of the differences between the index values for two countries cannot be interpreted meaningfully), we have carried out the non-parametric Mann-Whitney rank sum test to see if the rankings derived from H D I and N C H D I belong to the same distribution. Table 2 shows the corresponding U statistic and p-value for each of the five years. Since in all cases the statistic is significant at 0.01 level, the null hypothesis that the ranking given by H D I and N C H D I are similar is rejected, i.e. the N C H D I leads to a different ranking from that of the H D I. Whether the N C H D I ranking is more or less valid than that of H D I depends on whether the N C criterion is adopted or not.

Figure 3 shows, for the year 2004, the histogram showing the distribution of the rank difference between and N C H D I. Its apparent normality (with zero mean and a standard deviation of 12.9) is confirmed, at a 0.01 significance level, by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov-Lilliefors normality test. The same normality behavior happens (with similar means and standard deviations) for the other four years.

Figure 4 plots H D I and N C H D I versus Cumulative Global Population for year 2004. The H D I graph results from ordering the countries in decreasing order of H D I and accumulating their population in that order. The same is done for the N C H D I graph. Note that, since , the N C H D I graph is always below that of H D I and this implies that N C H D I presents a bleaker picture of global H D than the more optimistic H D I. Think that the horizontal line H D I = N C H D I = 1 corresponds to the Ideal Point given by the U N D P goalposts. Therefore, the lower the graph, the clearer is the work that has still to be done to bring the HD of the world population up to those goalposts.

Table 3 shows how many times each of the three H D I component indices gives the minimum that determines the value of the N C H D I. Note that the X G D P component has lagged behind in more than 50% of the cases, X L E in more than 35% of the cases and X E in only 10% of the cases. This seems to indicate that half of the countries should concentrate on improving the economic well being of their citizens, another significant number of countries should concentrate in improving their health and life expectancy and only a minority should worry most about the educational level of the population. Although the distribution was fairly stable for four years it seems that in year 2004 there was an increase in the number of countries with minimum value of X L E at the expense of component X G D P. This seems to imply that for some countries the X G D P improved enough to stop being lower than X L E B. This type of reasoning, however, must be made with caution since if the difference between the H D I component indices of a country is small then a small differential improvement may be enough for changing the component that is the minimum. It may also happen that both components decrease but one decreases less than the other by an amount enough to stop being the minimum. Therefore, the changes in the H D I component indices must be analyzed on a case-bycase basis. What N C H D I does, with respect to H D I, is to increase the visibility and individual importance of the component indices, a visibility and an importance that are highly diminished after the additive aggregation process performed by the H D I.

As for inter-temporal comparisons using the N C H D I, Table 4 shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between consecutive years for both H D I and N C H D I. It can be seen that in both cases there is a significantly strong correlation between the values of the indices in one year and the next and that the strength of the correlation is similar for both indices. The linear relationship between the N C H D I in consecutive years can also be seen in Figure 5, which shows a 3D scatter plot of the N C H D I for the last three years.

Finally, Figure 6 shows the temporal variation of the proposed N C H D I between 2000 and 2004. For comparison, the temporal variation of H D I over the same period is also shown. Note that, surprisingly, in both indeX Es negative variations have occurred in a relatively high number of cases. In general, the changes of N C H D I have been greater than those of H D I. Also, it can be seen that the changes in N C H D I are the largest for those countries with low N C H D I values.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

This paper suggests departing from the additive character of the H D I and adopting an N C criterion that assumes that the different H D I dimensions are inalienable and therefore cannot be traded off. The rationale is that so long as a crucial aspect of human development lags behind, the whole goal of human development is hindered. It makes sense, therefore, to try to identify and remove the most important obstacles that are impeding the integrality of this process. The usual way of aggregating the H D I components can mask existing problems, while adopting a N C approach highlights them.

The specific N C H D I proposed corresponds to taking the minimum of the values of the H D I component. This N C H D I is related to the Tchebycheff distance to the Ideal Point that represents the maximum values of the goalposts assumed by UNDP for computing the H D I. Several properties and features of the proposed N C H D I have also been presented.

Numerical results comparing the N C H D I and the H D I and their respective rankings for the last five years of data available are reported. They show that although the numerical values of both indices are highly correlated their rankings are not and that the N C H D I reflects and highlights possible imbalances in the H D I component indices. The N C H D I also allows for a more detailed analysis of the inter-temporal evolution of the H D I dimensions. Overall, the N C H D I provides a more realistic (i.e. less optimistic) assessment of the situation of H D than the H D I does. Finally, as it happens with the H D I, N C H D I can be applied not only to countries but also at the regional or local levels.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Booysen, F. (2002). An overview and evaluation of composite indexes of development. Social Indicators Research, 59(2), 115-151. [ Links ]

2. Cahill, M.B. (2005). Is the Human Development Index Redundant?. Eastern Economic Journal, 31(1), 1-5. [ Links ]

3. Desai, M. (1991). Human development: Concepts and measurement. European Economic Review, 35, 350-357. [ Links ]

4. Despotis, D.K. (2005a). A reassessment of the human development index with data envelopment analysis. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 56: 969-980. [ Links ]

5. Despotis, D.K. (2005b). Measuring human development via data envelopment analysis: the case of Asia and the Pacific. Omega, 33, 385-390. [ Links ]

6. Hopkins, M. (1991). Human Development Revisited: A New UNDP Report. World Development, 19(10), 1469-1473. [ Links ]

7. Kelley, A.C. (1991). The Human Development index: ´Handle with Care´. Population and Development Review, 17(2), 315-324. [ Links ]

8. Lozano, S. and Gutiérrez, E. (2008). Data envelopment analysis of the human development index. International Journal of Society Systems Science, 1(2), 132-150. [ Links ]

9. Lüchters, G. andMenkhoff, L. (1996). Human Development as Statistical Artifact. World Development, 24(8), 1385-1392. [ Links ]

10. Mazumdar, K. (2003). A New Approach to Human Development Index. Review of Social Economy, 61(4), 535-549. [ Links ]

11. McGillivray,M. (1991). The Human Development Index: Yet Another Redundant Composite Development Indicator?. World Development, 19(10), 1461-1468. [ Links ]

12. Morse, S. (2003). For better or for worse, till the human development index do us part. Ecological Economics, 45, 281-296. [ Links ]

13. Noorbakhsh, F. (1998a). A Modified Human Development Index. World Development, 26(3), 517-528. [ Links ]

14. Noorbakhsh, F. (1998b). The Human Development Index: some technical issues and alternative indices. Journal of International Development, 10, 589-605. [ Links ]

15. Ogwang, T. (1994). The Choice of Principle Variables for Computing the Human Development Index. World Development, 22(12), 2011-2014. [ Links ]

16. Ogwang, T. and Abdou, A. (2003). The Choice of Principal Variables for Computing Some Measures of Human Well-Being. Social Indicators Research, 64(1), 139-152. [ Links ]

17. Ravallion, M. (1997). Good and Bad Growth: The Human Development Reports. World Development, 25(5), 631-638. [ Links ]

18. Rawls, J. 1971. A Theory of Justice, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

19. Sagar, A.D. and Najam, A. (1998). The human development index: a critical review. Ecological Economics, 25, 249-264. [ Links ]

20. Sen, A. (1989). Development as Capabilities Expansion. Journal of Development Planning, 19, 41-58. [ Links ]

21. Srinivasan, T.N. (1994). Human Development: A New Paradigm or Reinvention of the Wheel?. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 238-243. [ Links ]

22. Trabold-Nübler,H. (1991). The Human development Index - A New Development Indicator?. Intereconomics, 26(5), 236-243. [ Links ]

23. Yoon, K.P. and Hwang, C.-L. (1995). Multiple Attribute Decision Making. An Introduction (Sage University Papers series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 07-104). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. [ Links ]