INTRODUCTION: FEMALE FIGHTERS -DRIVERS OR OBSTACLES FOR PEACE IN COLOMBIA?

"[T]he reintegration of the members of FARC-EP is undoubtedly the most critical task within the overall peace consolidation agenda" (UNSG, 2017).

In 2016, one of the most long-standing and protracted violent conflicts in the world took a positive turn: The Final Agreement between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) was signed. However, the peace process has not been met with widespread popular support, evidenced by the negative results of the referendum on the first draft of the peace agreement, in October 2016, and the victory of Iván Duque in the 2018 presidential elections, an outspoken opponent of the peace agreement.

One of the most contested elements is the socioeconomic and political reintegration of more than 13.000 FARC members, among them 7.000 former combatants (Angelo, 2016; Casey & Daniels, 2017). The disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) process has achieved significant benchmarks - with the FARC handing over its weapons under UN supervision and its political participation in the parliamentary elections in 2018. Nonetheless, the idea of impunity and political eligibility for former fighters who may have committed war crimes and human rights violations has been met with widespread resistance throughout the population. Additionally, FARC itself stressed the point that it never disarmed but only laid down the weapons and that the reintegration process is proceeding as a collective 'reincorporation', rather than in an individual way in order to maintain the group's cohesion.

Women constituted a crucial part of the insurgent group; they were estimated to make up approximately 23% of the FARC (Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2017). The rebels had recruited traditionally marginalized sectors of the population, like women, and had - partly based on Marxist ideology, partly in response to the war context - implemented a gender regime that was based foremost on capacities and not the sex of fighters (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). Many female combatants fulfilled traditionally male roles on the frontline and were part of the militia. They were combatants, guards, troop supporters, radio operators, money managers, instructors, and doctors, among other roles (Magnœs Gjelsvik, 2010; OPC, 2015). Even if women within FARC did not take part in the highest management levels of the group (Castrillón Pulido, 2015), politically they also served as leaders in the low and middle ranks, assuming positions of trust in the larger organization.

In the literature on DDR in general, the argument is made that it does not matter how female combatants came to a group (by their own free will, abduction or force), they generally are neglected during the DDR processes, and they are rarely considered for leadership during the reconstruction (see Rehn & Sirleaf, 2002; Shekhawat, 2015; Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015; Zirion Landaluze, 2012).

Therefore, many female combatants find it difficult to reintegrate into civilian communities, specifically in social terms, and they receive little support (see UN, 2006; UNDP, 2002; Zirion Landaluze, 2012). Communities may be distrustful towards female ex-combatants, while women themselves may feel that they do not fit in with the traditions and social expectations of their communities anymore, making it harder for them to settle down to a new life. Based on that literature, we have to assume that rather than being drivers of the peace process, female FARC ex-combatants could become an obstacle or even spoil it. Is this the reality in Colombia? How are former female FARC fighters able to transform their social roles during the reintegration process and how does this affect prospects for peace?

This article has a gender-based approach which we deem crucial to analyzing the Colombian case. Notably, we assume that gender impacts people's social roles and opportunities, their needs and rights. Therefore, we study how gender plays out specifically in Colombia in order to have a precise understanding of the role of former female FARC combatants within war and the post-conflict reconstruction. We find an extended body of research on DDR processes all around the world, e.g. Jennings (2007) and Munive & Jakobsen (2012) on Liberia; Torjesen & MacFarlane (2007) on Tajikistan or McEvoy & Shirlow (2009) on Northern Ireland. Since gender has been increasingly a cross-cutting issue in DDR, a diverse corpus of literature has begun to emerge. For example, Mazurana & Eckerbom Cole (2013) consider how DDR processes remain unaware of or downplay the impact of militarized gender relationships of women during armed conflicts. We also consider several case studies, e.g. Utas (2005) and Basini (2013) on Liberia, Macdonald (2008) and MacKenzie (2009) on Sierra Leone, Ketola (2017) on Nepal and Duzel (2018) on the Kurdish female guerrillas.

Particularly, in Latin America studies have explored gender aspects of female combatants' experiences especially in left-wing guerrilla groups, from the moment they joined them to disarmament, demobilization and life beyond (Dietrich Ortega, 2012, 2014; Gonzalez-Perez, 2006; Hauge, 2008; Kampwirth, 2002; Lobao, 1990; Luciak, 2001; Shayne, 1999; Viterna, 2006, 2013). Concerning Colombia, the academic interest in the chances and risks of reintegration of FARC women is rapidly increasing though we still miss systematic and comprehensive publications. Serrano Murcia (2013) analyzes all DDR processes in Colombia so far and concludes that in none of them have the disadvantaged position and the particular needs of women been considered. In addition, we find several studies which have focused their attention on the role of women before, during and after these DDR processes, and how their identities were constructed and deconstructed (e.g. Castrillón Pulido, 2015; Cifuentes Patiño, 2009; Esguerra Rezk, 2013; Herrera & Porch, 2008; Ibarra Melo, 2009; Jiménez Sánchez, 2014; Kunz & Sjöberg, 2009; Londoño & Nieto-Valdivieso, 2006; Magnœs Gjelsvik, 2010; Mejía Pérez & Anctil Avoine, 2017; Méndez, 2012; Nieto-Valdivieso, 2017; Ocampo, Baracaldo, Arboleda, & Escobar, (2014); OPC, 2015; Theidon, 2009). Until now, there have been few studies that generally analyze the current reincorporation process of former FARC combatants from a gender-perspective (e.g. GPaz, 2018), this article provides a valuable and pioneering explorative study of the transformation of the social roles of former female FARC combatants from a local perspective.

The article is based on a qualitative research design focusing on both the pers-pec-tives from former fighters and conflict-affected communities from the bottom up and not - as is usually done - top down in the political context. By drawing on extensive empirical research in so-called transitory zones and rural areas formerly controlled by FARC, we will show that there is a striking contrast between the existing DDR-literature, which takes a skeptical stance, and the more positive perception held both among fighters and the communities. Thus, we argue that former female FARC fighters can perform new roles at the local level and thus play a decisive role during the reintegration process in social, political and economic terms.

The present study is of high political and academic relevance. First, Colombia now faces a unique moment in its history. The reintegration of former combatants is pivotal for the success or failure of the peace process and will have path-dependent effects. Second, the article presents an original, in depth-case study on the DDR process of the FARC from a gender perspective and thus challenges some of the conclusions of previous studies, namely that the reintegration of female fighters is far more problematic than of their male counterparts. This situation is even more important in light of the fact that the 2016 peace accords in Colombia were the first in a global scale to include a gender perspective: during the peace negotiations, a sub-commission on gender was created to take into account the needs of women and LGBTI communities (GPaz, 2018). Thus, it is crucial to study what long-term impact that approach had and how it affected the peace implementation (O'Neill, 2015).

We proceed as follows: In the second section, we will outline our theoretical framework by linking the literature on DDR-processes with gender perspectives, namely Butler's performativity approach. We will also shortly describe our research methodology and data collection. In the third part, we will present in-depth our empirical data both from the interviews with former FARC fighters in transitory zones and the micro-survey in conflict-affected communities. We will conclude by linking our results to the current discussion on the peace process in Colombia and suggesting new insights for both political and academic thinking.

DEMILITARIZATION, DEMOBILIZATION AND REINTEGRATION: A GENDER-BASED APPROACH

The process of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) is considered an essential stage for the successful implementation of a civil war peace agreement. The main aim is to contribute to the security of post-conflict settings by supporting the transition of former combatants from the military to the civilian life and providing them with the necessary tools to become active participants in the peace process (Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015; UN, 2006; UNDP, 2002). The United Nations emphasize that DDR "has repeatedly proved to be vital to stabilizing a post-conflict situation, to reducing the likelihood of renewed violence" (UN, 2000b, p. 1).

Reintegration: Bringing former fighters back into communities

There is consensus in the academic literature that the reintegration stage presents more complex challenges than either disarmament or demobilization (Hagman & Nielsen, 2002; UN, 2000b). Following Torjesen (2013), reintegration can be defined as a "process in which fighters (1) change their identity from 'combatant' to 'civilian' and (2) alter their behaviour by ending the use of violent means" (p. 4). Both social and economic reintegration are long-term processes, while political reintegration often is a more immediate step. According to the literature, reintegration is a necessary precondition for the permanent cessation of violence, as it reduces the risk of impairing the peace process, as well as the recurrence of conflict (Hensell & Gerdes, 2017; Humphreys & Weinstein, 2007). Nevertheless, this process is highly contested and often problematic. Tull & Mehler (2005) argue that the presence of leaders who may have committed human rights violations during the conflict in the country's legal institutions often causes resistance in both affected communities and the general population. Thus, DDR alone cannot provide security and development to a post-conflict country but must be part of a broader political, economic and social national reconstruction strategy that requires significant coordination and unity of effort between the local, national and international (Ball & Goor, 2006; Hagman & Nielsen, 2002; UN, 2006; UN Women, 2009; UNDP, 2002).

Specifically, tensions can easily arise between former combatants and the conflict-affected communities into which ex-combatants are being integrated. On the one hand, ex-combatants will re-enter civil society and regain civilian status, but they may not have experience or memories of pre-war times (UN, 2006; UNDP, 2002). In this case, due to the war, their skills would be limited, and the market would be unable to absorb them. If former fighters do not find the opportunities to conduct a dignified life by having, for instance, a decent job, they may become obstacles to the peace process through criminal activity and the use of violence in the communities where they have been reintegrated (Buxton, 2008; UN, 2006; Zirion Landaluze, 2012). On the other hand, conflict-affected communities might have neither the capacity nor the desire to assist these former combatants as they might perceive them as a 'lost generation' due to their lack of education, training and employment (UN, 2006). For this reason, communities must see the opportunities presented by the peace process in order to not become obstacles to the process (Hagman & Nielsen, 2002; UN, 2000b).

The transformation of wartime roles to peacetime roles of female fighters

In the Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, adopted by the Security Council in 2000, the United Nations recognized the importance of gender justice as a crucial factor to social transformation after conflict (UN, 2000a, p. 5). Indeed, conflict is not gender neutral (Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015), it is a "gendered activity: women and men have different access to resources, power and decision making before, during and after conflicts. The experience of women and men in situations of tension, war and post-conflict reconstruction is significantly different" (Council of Europe, 2004, para. 1). Even though it is widely recognized that women and their specific needs and concerns should be included in the peace processes, they are often still overlooked by the DDR decision-makers (ILO, 2009; Myrttinen, Naujoks, & El-Bushra, 2014; Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015; UN, 2006; UN Women, 2009; UNDP, 2002).

Gender-based approaches emphasize that "gender is a social artifice. Our ideas of what women and men reflect are, nothing that exists eternally in nature. Instead they derive from customs that embed social relations of power" (Nussbaum, 1999, p. 5). Specifically, according to Nussbaum (1999), Butler's theory of gender performativity is relevant, claiming that "when we act and speak in a gendered way, we are not simply reporting on something that is already fixed in the world, we are actively constituting it, replicating it, and reinforcing it" (p. 7). A gender-based approach in line with Butler (1990) thus requires us to surmount binary categories such as men/women, masculine/feminine, perpetrator/victim, in order to understand how war time and peace time roles are constantly reconstructed and to create opportunities to transform them.

During the conflict, many female combatants enjoyed parity, power and freedom of choice especially in left-wing armed groups that centered women's emancipation and gender equality as cornerstones of their fight (Castrillón Pulido, 2015). Hence, women acquired more responsibilities and increased their political participation and incidence in decision-making processes at the low and middle ranks (Zirion Landaluze, 2012). However, this wartime empowerment is temporary and ambivalent. The failure to recognize women as perpetrators not only strengthens the masculinized image of war but incentivizes their marginalization from peace-building processes and the reinforcement of existing gender inequalities. Women are often not visible in the peace processes, they are excluded from the formulation, implementation and evaluation of DDR, and they are rarely leaders during reconstruction (Rehn & Sirleaf, 2002; Shekhawat, 2015; Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015; Zirion Landaluze, 2012).

The reasons behind this exclusion vary. First, as Shekhawat (2015) argues, patriarchy is intensely embedded in most societies and social existence. Masculinized leadership decides the timing and intensity of the involvement of women in war and peace. Consequently, the role of women within conflict is often undermined and to some extent not acknowledged, reflected in post-conflict situations and depriving them of active participation in and benefits from the DDR process.

Second, it is often assumed that men are the primary threat to the post-conflict stability and security and thus that they should be the main focus of DDR (UN, 2006; Zirion Landaluze, 2012). The dominant discourse in peace processes all over the world portrays women as victims, spectators or prizes (Herrera & Porch, 2008; Shekhawat, 2015); therefore, they are not included in the peace process because they are assumed not to represent any risk to it.

Third, women are often forced to re-accept their 'traditional'roles in society (Dietrich Ortega, 2010); they have to suffer the stigmatization that they are violent, and therefore unacceptable, women (Méndez, 2012; OPC, 2015). They have to confront community shaming, particularly if they are single mothers or have a sexually transmitted disease; and they have to find a livelihood which can lead them to prostitution should employment prove difficult to find (Shekhawat, 2015). Hence, former female combatants are triply alienated in post-conflict situations - from their former group, from the state and from their new community - "while their group neglects them and the state is apathetic, society stigmatizes them" (Shekhawat, 2015, pp. 16-17). In this sense, mechanisms are not built-in to guarantee their active political, economic and social participation in the reintegration process.

An effective political reintegration offers former combatants the opportunity to improve levels of representation and legitimacy of institutions by articulating their grievances and demands through legitimate and peaceable channels rather than by taking up arms (Buxton, 2008; UN, 2006). However, women often face marginalization in formal political participation spaces, e.g. newly constituted parties tend to ignore the current quota for female participation or to assign a quota at the end of the electoral list, where there are few chances of women being elected (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). Economic reintegration shall help former combatants become productive members of their communities either by obtaining long-term gainful employment or by initiating other income-generating activities, including agriculture, that may support them and their families (Hagman & Nielsen, 2002; Torjesen, 2013; UN, 2006). Women often have limited economic possibilities, limited rights and limited access to productive resources such as credit, land, housing, training, employment opportunities and technology (UN, 2006; UNDP, 2002). What is more, they may have acquired different skills during the conflict that are not certified (Farr, 2002) or that do not fit the 'traditional' and proper work for them. Despite the fact that many female former combatants are interested in pursuing non-traditional professions, they are often given training and job opportunities that are associated with female 'traditional' professions, such as domestic tasks, tailoring, secretarial jobs, and hairdressing, among others (Dietrich Ortega, 2010; Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015).

The social reintegration process should encompass different measures to reconstruct social ties and social cohesion by allowing former combatants to become positive agents of change (Torjesen, 2013; UN, 2006). Women, and especially the ones that joined armed groups voluntarily (Rehn & Sirleaf, 2002), face increased stigma and discrimination once they are in the communities due to their inability and resistance to readapting to 'traditional' roles in society (UN, 2006; UNDP, 2002; Zirion Landaluze, 2012). In other words, as Rehn & Sirleaf (2002, p. 117) state, "communities may be suspicious of women returning from battle, and the women themselves may no longer feel they fit in". Thus, women are often driven into submissive relationships, or they are forced to survive while being marginalized from the community (Farr, 2002).

In summary, for the DDR process, "there is an urgent need to challenge the traditional understanding of men and women, war and peace, perpetrator and perpetrated since the post-conflict scenario may be equally gendered, as it is the conflict scenario" (Shekhawat, 2015, p. 9). In other words, there is a risk that peace processes might reflect and thus perpetuate the war context, for example, that decision-makers will strengthen, legitimize and reproduce patriarchal systems and will thus obstruct the path toward sustainable peace (Shekhawat, 2015).

Research Methodology

This article presents results from a research project that applied a mixed method research design (Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017) based on instruments of quantitative community-based surveys and ethnographic field study (Atkinson & Delamont, 2010; Bryman, 2012). Colombia presents a unique single-case study (Yin, 2003; cf. Gerring, 2004), given its combination of relatively long-standing democratic tradition and stable political institutions despite wide-spread human rights violations in one of the longest civil wars in the world. In addition, in contrast to many other cases, the peace process was primarily internally driven and not imposed from the outside. Original empirical data were acquired through anonymous, semi-structured key informant interviews (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006; Warren, 2001) that provided essential information on the reintegration policies and the perception of the main stakeholders on the national level. These primary data were complemented by a bottom-up approach to identify the perception of former fighters and grievances in conflict-affected communities. Specifically, a data-source triangulation was conducted in order to make use of several perspectives (Flick, 2018, p. 530; on triangulation Taylor, Bogdan, & DeVault, 2015).

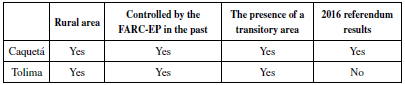

Data were collected during two-month fieldwork in two Colombian territories, allowing for case-specific variation: Caquetá and Tolima (Gerring & Cojocaru, 2016). Both regions were profoundly affected by the conflict and had been under the control of the former FARC. After the consolidation of the 26 "zonas transitorias de normalización", or Transitory Zones, where the disarmament and demobilization processes took place, the rebel group abandoned more than 98% of the territory that they used to occupy (PARES, 2017). After the demobilization process, Transitory Zones were transformed into ETCR (Espacios Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación or Territorial Area for Training and Reincorporation) in order to conduct the reintegration process, which we find in both regions.

Anonymous semi-structured in-depth interviews with former female and male FARC combatants (DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006; Warren, 2001) were conducted to reconstruct "perceptions of events and experiences", in this case about their roles during the armed conflict and how they perceive the reintegration process to the civilian life. In order to contrast the information of the interviews with the daily life of these former fighters in the ETCR, two-month participant observation was applied (Di Domenico & Nelson, 2016). In order to have different perspectives about the peace process, communities with varying approval rates in the 2016 referendum were chosen for data collection (Plebiscito, 2016). To maintain the anonymity of former FARC fighters, we will not expose the precise name of the communities and ETCR (see table 1). Though we tried to have as much variation as possible, the selection of the two ETCRs for FARC interviews might expose biases in the results in two ways: Firstly, all interviewed former FARC fighters were still living in the transitory zones, thus showing a generally high level of commitment to the peace process and the approach to collective reincorporation. This outcome might frame the previous experience within FARC and the current perspectives in a more positive way. Secondly, the two areas were previously under full FARC control; thus, we are not able to fully apply results from both the interviews and the micro-survey to regions which are still contested between different armed groups. However, given the limits of accessibility and security criteria for field research, we still assume relatively high reliability and validity of our data based on the robustness of the results across the two compared cases.

Finally, to contrast the former fighters' perceptions with the ones of the conflict-affected communities where former fighters are being reintegrated, a community-based micro-survey with 75 participants in each of the municipalities in Caquetá and Tolima was conducted (Brück, Justino, Verwimp, & Tedesco, 2013). This method intends to "facilitate the study of the microfoundations of war because they allow researchers to obtain fine-grained data on variations in individuals' attitudes and behaviour" (Eck, 2011, p. 165). Questions were partly based on the last 2016 Americas Barometer Colombia (Galvis Ramírez, Baracaldo Orjuela, García Sánchez, & Barragán Lizarazo, 2016), specifically regarding the peace process and reintegration of former FARC combatants. Purposive, quota-based sampling was used in order to reflect the variety of perceptions in the conflict-affected communities. The sample reflects, to a large extent, the structure of rural communities; thus, we can conclude that a broad variety of opinions is included, which represent the opinions of conflict-affected communities.1

PROSPECTS FOR PEACE: REINTEGRATION OF FARC FIGHTERS IN COLOMBIA

Colombia has endured the longest-running armed conflict in Latin America. For more than 50 years, there have been successive waves of confrontation between the government, the guerrillas, paramilitary forces, and organized criminal groups surrounding the drug market (GMH, 2016). Given the political background of the conflict, with grievances from the local populations as a driving force, Colombia can be identified as a Protracted Social Conflict, a term coined by Edward E. Azar to denote a "prolonged and often violent struggle by communal groups for such basic needs as security, recognition and acceptance, fair access to political institutions and economic participation" (Azar, 1990, p. 93). The rebel group FARC was founded on a strong foundation of Marxist ideology, seeking justice for marginalized social groups and appropriate access to land by all available means. Even though the group developed into a criminal (even labelled terrorist) organization, its political agenda always remained part of the fight (Phelan, 2017).

Colombia has experienced five different instances of collective DDR in the past 30 years (Angelo, 2016). Specifically, the transition of the Patriotic Union (Unión Patriótica, UP) into the political sphere largely failed, due to a lack of protection for demobilized fighters and refusal by the FARC to renounce armed struggle (Angelo, 2016). In contrast, the political reintegration of the guerilla group M-19 in the early 1990s is often mentioned as a positive case, "offering the FARC a model for the organization's transition to post-conflict" (Angelo, 2016, p. 3). Accordingly, alongside amnesty and security guarantees, the demands for social reintegration and participation in political life have been a pivotal element in the peace negotiations, in order to assure FARC-EP's approval (Feldmann, 2017).

War-time roles of former FARC fighters

According to empirical studies, Colombian gender norms resemble those of many other countries in the world, as women are portrayed as peaceful, caring, maternal, apolitical victims, while men are believed to be more aggressive and confrontational (Anctil Avoine & Tillman, 2015; Dietrich Ortega, 2014). Even if the participation of women in the armed conflict is recognized, it is perceived in ways that ignore their agency (Anctil Avoine & Tillman, 2015, p. 217). However, this dominant imaginary in the Colombian society is contrasted by the insurgents' own gender regime. They mobilize gender constructions to create a distance between them and the broad social order (Dietrich Ortega, 2014) in order to allow the combatants to assume roles against the old order where social injustices prevail. Hence, the binary categories identified by Butler (1990), where men are conceived of as perpetrators and women as victims, were challenged by the fact that women were not excluded. On the contrary, they were entirely part of the insurgent project (Dietrich Ortega, 2012, p. 494). Thus, also in line with Utas (2005) and the findings from our interviews, being perpetrators and victims for FARC women was not mutually exclusive but simultaneously formed part of their social role. In order to foment cohesion and unity among the group, and to take advantage of everyone's capacities, female and male combatants had the same tasks, as interviews in Caquetá and Tolima confirmed and this quote from a former female FARC fighter illustrates:

Here men and women contributed shoulder to shoulder, that if the man had to carry 50 pounds, we women too, that if the man went to combat, the woman also went. Like this, women within FARC earned respect and earned the position to be equal to men. (Woman 2, Caquetá, 19.02.2018)

Hence, by being included and considered equal to men, female former combatants had the opportunity to have agency, a term used by Dietrich Ortega (2014) that refers to "the actions of a political actor, which recognizes both the capacities of the people who exercise and the spaces generated by the structures in which the concrete person is immersed" (p. 89). Female FARC combatants enjoyed relative freedom and control over their choices, as well as their service in the group gave them a sense of accomplishment and an opportunity to play important roles (Gonzalez-Perez, 2006; Herrera & Porch, 2008; Méndez, 2012; Nieto-Valdivieso, 2017). As Woman 1 in Caquetá said: "One says good, I am useful in a fight, I am useful in a process, ... they recognize my career, my work, my sacrifice, I feel useful because they are taking me into account" (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018). Militant women's agency was also strengthened by a rupture in their previous life practices, which opened other options for them that would not have been possible outside the organization (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). These opportunities may include leaving home, being politically active, participating in a project of national scope or getting access to training (e.g. Woman 8, Tolima, 03.03.2018). Consequently, the conditions in the insurgent group allowed women to be recognized for their capabilities and merits, to get access to positions of responsibility and assume leadership positions within the organization (Dietrich Ortega, 2014), even if they did not achieve any position in the FARC secretariat (Castrillón Pulido, 2015).

Other studies take a more critical stance on women's role within the FARC guerilla group and argue that sexuality played an important role: Herrera & Porch (2008, p. 621) found that "guerrilleras [female ex-combatants] in the FARC use[d] their sexuality to gain power and influence without the headaches of responsibility, or submitting to the drudgery of the FARC's stiff education and training program required for promotion to positions of leadership". Our findings do not confirm this though, in line with some other studies (Kunz & Sjoberg, 2009; Méndez, 2012; OPC, 2015), one of the females interviewed assured that the women of the commanders indeed had certain benefits. Another aspect that is critically discussed in the literature is reproductive rights where elements of femininity came into tension, to for instance, maternity (Esguerra Rezk, 2013; Magnœs Gjelsvik, 2010). Within FARC, practices such as forced contraception and forced abortions were based on the idea that motherhood was incompatible with the armed revolutionary struggle (Méndez, 2012). In the interviews, we found that female FARC ex-combatants were fully aware of these practices, but they did not conceive them as something forced, even idealizing these practices: "They performed abortions out of necessity. I learned to perform abortions, and I did it just for necessity and for the convenience of the compañeras. ... Never in the course of FARC's life, ... someone was forced." (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018)

Despite the previous contrasting findings, there is a common ground in the studies mentioned above (Esguerra Rezk, 2013; Herrera & Porch, 2008; Méndez, 2012): the opportunities of mobilization did generate confidence in women. They assumed that they could perform equally or even better than their peers (Dietrich Ortega, 2014): "During the resistance, women showed that they were much more resistant and it is a task that we as mujeres farianas assumed and that is why men always respected us and always considered us their compañeras." (Woman 2, Caquetá, 19.02.2018)

Interviews with former male FARC combatants confirm this perspective; all men interviewed in Caquetá and Tolima affirmed that women were equal to them, some even recognizing that women were coping better with the challenges of resistance. The female comrade was considered a different type of woman - different than the mother, wife, sister or daughter. They were rewarded with certain roles acknowledged by male comrades and perceived as active participants, politically empowered compañeras willing to fight with weapons for a change in the system without being seen as a threat in the revolutionary endeavor (Dietrich Ortega, 2012, 2014):

They [women] often had more courageous behavior than many of us men, many times. ... Our compañeras were commanders, professionals in dentistry, professionals in medicine, professionals in communications, professionals in filming, professionals in propaganda, professionals in the art of mobile guerrilla warfare. They also occupied a trench, like any man; they fought men, they went to the battlefield with a machine gun, with a mortar, with a rifle, they were nurses; they were present in all contexts. (Man 4, Caquetá, 18.02.2018)

This finding somewhat contrasts few previous studies which found a more negative perception of female combatants by their male comrades, e.g. denouncing them as "puta" [bitch or slut] (e.g. Méndez, 2012, Theidon, 2009). The difference, however, can be explained by the fact that all male and female combatants interviewed in our study are still living in the same collective, thus having either more positive views or hesitant to expose their negative views.

To sum up, we can confirm what Dietrich Ortega (2014) states, that in the FARC insurgent organization, by and large, the identities based on partnership are more representative than the ones based on gender. Even though men and women within the FARC were not able to entirely "escape" from the Colombian macho society, cases of machismo were rather the exception. Hence, dichotomies such as women/ pacifism, men/militarism and victim/perpetrator are insufficient for understanding the complexity of the processes involved in women's participation in armed conflict (see also Anctil Avoine & Tillman, 2015, p. 225). Being part on an insurgent group that aims to overcome traditional roles thus provides both female and male combatants with an idea of gender equality.

Following Anctil Avoine & Tillman (2015, p. 221), however, "even when women are considered equal in combat situations, they are not necessarily accorded the same status in everyday life once war is over." In other words, the participation of women in combat allows them to escape from gender attributes that marginalize them in society while offering them the possibility of increasing their agency. This underlines the importance of a transformation of their roles once they come back to society, which will be analyzed in the following section.

A free choice to make: perspectives on reintegration from former female FARC fighters

The main goal of DDR programs is to allow former fighters a new life as civilians. The adaptation to or construction of new social roles is especially challenging for FARC fighters, given the fact that gender-equality was a significant characteristic in the guerrilla. One male fighter even went as far as arguing that "in FARC we have managed to overcome all that [machismo]" (Man 3, Caquetá, 21.02.2018). Based on the interviews in Colombia, former female FARC fighters share an interest in contributing to peace from different angles: "I know that my dedication and remaining days of life will be dedicated to the struggle because . the implementation of the agreements has not ended. We have to begin to build those agreements in daily life" (Woman 3, Caquetá, 21.02.2018). We will separately analyze the three different areas of reintegration efforts (political, economic and social) though they are largely connected. For example, missing economic opportunities will inhibit further political participation of ex-combatants in the long run.

Political Reintegration

Previous studies have been skeptical regarding the active participation of women in political life since they are usually removed from party lists or demoted to less powerful positions (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). In contrast, in the early stages of the reintegration process, former female FARC fighters were actively involved in consultations at the national level, as this quote shows: "Woman X travels a lot to Bogotá, to those talks, meetings, and she is part of the party. So is Woman Y. Woman Y is really important in the party." (Woman 3, Caquetá, 21.02.2018). As of now, female FARC fighters show a deep interest in and willingness to take over political responsibility at the local level: "If a number of people agree that I can reach a Mayor's Office or City Council, I am willing to put my efforts and my knowledge to run a municipality, with the support and technical advice of many people." (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018). In addition to that, at the elementary political level, women were able to shape actively the decision-making process in ECTRs themselves and have been taking leadership positions: "Usually, we go to an assembly to appoint a board or something and, . we always guarantee women's participation." (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018)

Political ambitions by female ex-combatants are supported by their male counterparts. During the reintegration stage in Caquetá and Tolima, men continue to perceive their female comrades not based on gender, but for their capabilities: "The movement does not differentiate between feminine or masculine ability to develop a specific task, especially in politics. If it was not like that during the war, it will be much less now in politics." (Man 9, Tolima, 05.03.2018)

Beyond the opportunities offered to them, former female FARC fighters clearly identified risks and obstacles for their political reintegration: Firstly, though a majority of them wanted to vote during the national elections 2018, only a minority was able to do so due to some specific regulations in the registration procedures presenting a systematic obstacle for active voting rights. Secondly, the majority of former fighters interviewed raised concerns regarding their active participation since they missed guarantees from the side of the Colombian state. Indeed, during the parliamentary elections in 2018, the newly founded party FARC stopped its public campaign due to death threats and harassments. The consequences were mostly felt at the local level since the party as such was already reserved ten seats in parliament by the peace agreement. This quote illustrates well the fears created:

The challenge that we are already facing as a political party is hard because you have noticed that over time, with the implementation there have been several difficulties that sometimes makes you scared to go out. ... The issue of reincorporation is tough, . you have noticed with the elections how things are, . you have looked how they treated us, then things get complicated, and I say that it should not be like that. If within the agreements regarding political participation, it was stated that all the parties have the guarantees to participating, and they cannot hinder each other, then why is this happening? All that was agreed has not been fulfilled. (Woman 7, Tolima, 04.03.2018)

Economic Reintegration

Regarding economic reintegration efforts, we do find a pattern in the literature that women receive fewer benefits from DDR programs and that they often become ensnared again in traditional social roles and domestic work (Dietrich Ortega, 2010; Esguerra Rezk, 2013; Shekhawat & Bishnu, 2015). Colombia offers a differentiated picture, the majority of interviewed former female FARC fighters underline three points: Firstly, women want to have free choice. Thus, some women recognized the advantage of more traditional jobs, such as manicurist or hairdresser, e.g. concerning the health situation, but are willing to have these jobs for legitimate and praiseworthy reasons independent of whether these jobs are considered to be stereotypically for women or not. Secondly, we can observe a clear expectation to be able to use the skills they acquired during wartime:

In the vida fariana, my profession was nursing and bacteriology. . I made a physiotherapy course, and I exercised it for many years, and I also did the clinical laboratory course, and I set up two clinical laboratories. . I was trained by a bacteriologist from Bogotá who worked in an institution, she came and taught us so much that in the end, she said 'mijita, do not feel incapable of rubbing shoulders with any bacteriologist just because you are without a diploma. . One felt very useful in different things, and therefore one had the recognition of the people. (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018)

And, thirdly, female FARC fighters showed a strong willingness to participate in further education programs. In this sense, education and training are fundamental aspects for the economic reintegration of these women:

The wish is not to stay there as if we were very clumsy but to try to get out of those stages . because, otherwise we would always end up being the employees of many people who have been able to study and are already working. So if we talk about empowerment, we have to talk about the fact that we have to be educated, we have to be formed, we have to be professionalized so we can say I am an ex-combatant, but I am a technician in agronomy. (Woman 1, Caquetá, 17.02.2018)

Participant observation in the ETCR supports the empirical results from the interviews, notably that women are a vital part of the daily economic life in the transitory zones. However, one of the crucial preconditions that was identified by all former fighters for a successful economic reintegration was clearly the ownership of land as this is the only possible path to building their own independent life and sustaining themselves - keeping in mind that the FARC was a guerilla consisting mostly of peasants. For them, it is indispensable to have proper and dignified means of life since the help of the government is temporary and does not cover all their needs:

The base for us is the land. ... To be able to sustain ourselves and for our people to think about the future, the only guarantee is that they can have land because we come to a normal life, we are laying down our arms, we are leaving our military life to become civilians and that means a normal life, and how is it? If you are going to live in the countryside, you need a piece of land to cultivate and make your family life. (Woman 2, Caquetá, 19.02.2018)

The importance of ownership of land for a self-sustainable reintegration process is exemplified by the fact that the two ETCR's differ considerably in this regard: In Caquetá, former combatants managed to buy land and have many productive projects like cultivating pineapples or conducting other activities that generate income. On the other hand, in Tolima, due to different conditions, ex-combatants have not been able to buy land and were thus under pressure to work in neighboring farms.2 In consequence, many have left for the cities or other places to find a proper job, because the Colombian government has not fully complied with the peace agreement.

Social Reintegration

Social reintegration is, according to existing studies, the context where women face the most pressure to assume socially constructed traditional roles in peacetime compared to war times (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). Often, among women, significant uncertainties and suffering prevailed, since they could not achieve their former goal of taking power, or because they had lost the organization and the collective project. This fact was also clearly seen in the interviews conducted with both female and male ex-combatants:

There is something that, at some point, makes me feel nostalgic: It is when we signed the agreement. Until then, we were in a small bubble, the small bubble of the familia fariana. That bubble had contained an atmosphere where all the principles were. . When we signed the agreement, we came here and that atmosphere at a certain moment breaks and the ultraviolet rays of the anti-values that are in Colombian society began to arrive, . and with the woman it is the same. ... We are in this exercise of not losing that, here we have to take that atmosphere and keep trying to reconstruct it from all sides. (Man 3, Caquetá, 21.02.2018)

This result is in line with other studies which argue that even if some women remember traumatic moments as members of the organization, they consider that being in FARC was a happy time in their lives: full of affection, love, friendship and comradery (Nieto-Valdivieso, 2017). With regard to gender-equality, former female FARC fighters affirmed that they still feel equal to their male counterparts, that they have been trying to keep this equality and to promote it to the society where they are being reintegrated: "I have spoken to them a lot, when I go there, I talked a lot about gender. I have told them that we as women have to earn respect, . that they have to value themselves as women, that we do not have to think that we only belong in the house but that we have the right to other things." (Woman 7, Tolima, 04.03.2018). Interestingly, even the male ex-combatants want to play an important role in promoting this equality in the broader Colombian society:

From the ETCR, we believe that the patriarchal culture should be eradicated and changed. Based on that, then we can give that recognition to the woman so that she also exercises the controls and directions within the government, within the institutions, within the specialties or sciences. So, the woman ceases to be an apparatus that only has her as an organ, as a reproductive instrument and not as a person, a woman with rights and abilities to project herself further in life and take society forward as such. (Man 4, Caquetá, 18.02.2018)

However, in line with studies that have found that equality among female and male combatants tends to disappear rather quickly (Dietrich Ortega, 2014), interviews and observations in the ETCR indicate a first trend: Many women have perceived the reintegration process as a form a 'liberation' of reproductive capacity which, during the war, impeded insurgent women's ability to have children (Dietrich Ortega, 2014). There is a 'baby boom' (Cosoy, 2017) that is evident both in Caquetá and Tolima. In contrast to the Colombian society, the ambition to continue both as a woman having children and as a woman taking over professional tasks according to her capabilities is still vivid and shared both by female and male ex-combatants. However, when it comes to day-to-day social roles, some women confirm that they returned to play the traditional roles that society dictates for them (e.g. Woman 3, Caquetá, 21.02.2018). Even if not discriminated against in the ETCR, both women and men cannot escape from the traditional Colombian culture and the dynamics of the society. Results from participant observation show that gender inequality was increasing and that typical Colombian gender roles (e.g. machismo) were visible, especially during social events.

A "friendly" woman: perspectives from conflict-affected communities

A vital element of the peace process is the acceptance of the conflict-affected communities where former combatants are being reintegrated. Colombia's post-conflict stage is challenging - with a massive gap between FARC's gender equality approach and thus the wartime role of empowered and capable women and the more traditional Colombian society where FARC women are expected to perform new peacetime roles. Indeed - and in line with the literature - former female fighters are specifically afraid of the stereotypes and conceptions that the population has about them which impedes their process of reintegration:

The government and certain social classes still stigmatize us, you, for being a former combatant, cannot have a job, you, who were a female combatant, no, you are very cruel. .We are civilians, but in our mind, . we still classify ourselves as guerrilleros. That is a title that we won, and nobody is going to take it away from us even if they say that we are ugly, . the bad guys. (Woman 6, Tolima, 02.03.2018)

Based on the results from the 150 questionnaires, however, we do see a differentiated perception of former FARC fighters among the population in the conflict-affected communities. In general, a large majority of the respondents in Caquetá and Tolima support the reintegration process of former combatants into society (see Graph 1). Contrasting to the literature (see for instance O'Reilly, 2015), more men support the process in both Caquetá and Tolima (86% of males to 82% of females / 87% of males to 78% of females). Also, in both places, non-victims support the reintegration process to a higher degree than the victims of FARC violence (85% to 83% and 85% to 79%). This result is attention-grabbing as far as it is generally believed that victims support the peace process in Colombia and that those who have not been directly affected by the conflict tend to reject it.

Question: Do you think it is important that ex-combatants of the FARC are reintegrated into society? [Yes; No]. All the categories are present.3 Source: Authors.

Graph 1 Level of acceptance of the reintegration of former FARC combatants into the society

In contrast to both the arguments formulated in the literature and the perceptions by former FARC members, among female FARC fighters, we neither find indications of stigmatization nor rejections of the reintegration process. Many respondents in Caquetá and Tolima even believe that women could be reintegrated more easily into society, though the majority sees no significant difference between female and male former combatants.

Question: Who would you believe that can be reintegrated more easily into civil life: a demobilized man or a demobilized woman? [Demobilized man, Demobilized woman, Both, None]. All the categories are present. Source: Authors.

Graph 2 Perception of the reintegration process by gender of the former combatants

The results of the questionnaires also exhibit a surprisingly positive image of former FARC fighters among the conflict-affected communities. Interestingly, graph 3 on all former fighters and graph 4 on former female fighters show that there are differences in the perception. While all fighters, in general, are perceived as 'friendly', women are much more often linked to characteristics such as 'hardworking' and 'vulnerable' than all fighters together, where descriptions such as 'dangerous' dominate more.

Question: What is your perception of the ex-combatants of the FARC? [Friendly, Violent, Lazy, Hard-workers, Dangerous, Vulnerable, None, Other]. All the categories are present.4 Source: Authors.

Graph 3 Perceptions of conflict-affected communities of former FARC combatants

Question: What is your perception of former female FARC-combatants? [Friendly, Violent, Lazy, Hard-workers, Dangerous, Vulnerable, None, Other]. All the categories are present. Source: Authors.

Graph 4 Perceptions of conflict-affected communities of former female FARC combatants5

Summary of results: community-based reintegration and prospects for peace

Based on the above-mentioned empirical data, we can carve out four main arguments on the reintegration process of female FARC ex-combatants:

Firstly, both women and men within FARC support a robust political role of former female fighters. The elections in 2018 proved to be a crucial step - albeit few women voted due to the previously identified registration problems. Remarkably, these women are willing to participate in the political arena of the country by running for local elected office. These traditional forms of political participation are crucial factors for the sustainability of the peace process insofar as former combatants are now able to channel their demands through peaceful and legal means. However, based on electoral results in the parliamentary elections in 2018, Colombia resembles somehow reintegration processes in other countries in that only two seats out of ten will be taken by women (as of June 2018). It is thus yet to be seen whether local elections in 2019 will confirm this underrepresentation. Nonetheless, there are other ways in which they are being politically engaged at the local level; for instance, in the ETCR where they have assumed leadership roles that male comrades acknowledge and appreciate.

Secondly, we do observe an evident willingness on the side of female ex-combatants to transform their roles in economic terms - thus to acquire jobs and open small businesses based on landownership, allowing them self-sustainable development. The data show a strong desire on the side of former combatants for their capabilities to be recognized and upgraded with further training and education programs. Interestingly, some of the women interviewed indeed intend to work in more traditional roles, e.g. as hairdressers, which is entirely in line with their gender concepts and their agency, notably the desire to have free choice.

Thirdly, the results regarding social integration indicate that the transformation of social roles is indeed quickly happening, evidenced in patterns both of FARC's approach to gender equality and already some few instances in the traditional Colombian machismo culture. By and large, women and men have the same responsibilities both in private and in public life and share the interest of expanding gender equality throughout society.

Lastly, questionnaires in conflict-affected communities falsify claims in the literature about patterns of stigmatization of fighters, specifically female fighters. To the contrary: The overwhelming majority of the 150 respondents support the reintegration process of FARC fighters. Female fighters even get higher approval rates and are assigned more positive characteristics than male fighters.

CONCLUSION: CHANGING ROLES OF FARC FIGHTERS - CHANGING ROLES OF WOMEN IN COLOMBIA?

During the war, female FARC combatants changed the traditional roles of their previous lives and became empowered by new roles within the combatant's daily routine. FARC women were able to get trained in various areas, they conducted the same tasks as their male counterparts, and they took leadership positions. Female combatants gained the respect of men, who perceived these mujeres farianas6 as courageous and women of decision that fought like any man, which made them different from the rest of the women in society and allowed them to be self-confident about their abilities. The gender regime within FARC where combatants were not treated according to their gender but to their capacities, enabled women to achieve a high level of agency. Even though obedience to military orders by highest male guerilla ranks were part of the daily life of violent insurgency in the context of war, and even if women were not part of the leadership at the highest level, they were transcending the traditional roles imposed on them in the Colombian society and pursuing an intense level of activities (cf. on the definition of agency Dietrich Ortega, 2014).

However, as high as the self-esteem of female fighters was during the armed conflict, the gap from the role of women in the traditional Colombian society is also markedly large, especially at the local level. Based on academic literature, we would thus clearly expect a more problematic reintegration stage for female than for male ex-combatants - in two distinct ways. Firstly, equal treatment tends to disappear rather quickly in the post-conflict stage. Secondly, women face far more challenges than men - due to the socially constructed roles, communities tend to label them as transgressive women. Moreover, they are marginalized in the DDR programs because the society and especially the decision-makers overlook their active participation in the conflict and perceive them usually as victims (cf. Anctil Avoine & Tillman, 2015; Dietrich Ortega, 2014). Thus, binary categories such as women/men, pacifist/violent, victim/perpetrator often dominate post-conflict peacebuilding (cf. Butler, 1990).

In contrast to these arguments, our research results draw a different picture of former female fighters and prospects for their reintegration in Colombia. Based on the findings from Caquetá and Tolima, we argue that neither ex-combatants nor conflict-affected communities oppose the reintegration of FARC into the society. Even if it is believed that the general public opinion in Colombia portrays former female combatants as transgressors of the traditional roles, conflict-affected communities in Caquetá and Tolima have in general a positive perception about them, which may facilitate their process of reintegration within these communities.

However, our results confirm the literature to a certain extent, that these positive portrayals are also partly accompanied by victimization of former female fighters - at the expense of recognition of their own agency:

When I had a surgery, a nurse said some things, and I realized it, so I told her: look, I know you know that I am a guerrillera, and it is true. .You were saying that there we were raped, that we were forced to have relations with the bosses, that we were forcibly recruited, that was what you were saying, . and you are very wrong. I told her I am a guerrillera, at no time did they rape me, they never recruited me forcibly, I told her, I came because I wanted because I liked the guerrilla, I told her, no one is forced there. (Woman 7, Tolima, 04.03.2018)

Both interviews with ex-combatants and questionnaires in conflict-affected communities reveal that the typical stereotypes referred to by Butler (1990), e.g. men-perpetrators / women-victims are nevertheless not fully applicable to the local level in Colombia. During the conflict, women were active and equal to men in their participation. They also oppose transforming their social roles to traditional forms but want to lead on an equal footing to men in the construction of their communities during the peacebuilding stage. These binary categories also do not work in the communities and therefore also do not work in crucial parts of the Colombian society, as this study was able to show.

According to the perception of former fighters, key obstacles that exist are mainly related to the stagnating implementation of the peace agreement, notably the distribution of land for economic reintegration and (security) guarantees for political integration. This is also reflected in the most recent report of the NGO Gpaz (Género en la Paz) at the publication date of this article: According to the data published in October 2018, from the 109 gender-related dispositions in the peace agreements, 70,64% were normatively processed (e.g. through laws or constitutional reform) while only 14,68% were already implemented at an operational level. Particular data concerning the reincorporation process are only slightly more positive, with 85% normatively processed and 20% operatively implemented (Gpaz, 2018). Thus, in order to support the swift and self-sustainable transformation of former rebels into civilians, it is vital for all governmental and international agencies to offer and strengthen these guarantees and to implement land reforms. Moreover, projects to support female fighters are specifically valuable about training and education and to support their leadership roles. These measures are indispensable to continuing the strengthening and transformation of the agency they acquired during the conflict into a peaceful and legal setting and to give women equal opportunities to make independent decisions.

On a positive note, though, the "DDR process ... creates openings for new patterns and performances of gender relations within society" (Anctil Avoine & Tillman, 2015, p. 223). It is a unique opportunity for Colombia to increase gender-equality, empower women and thus support the transformation from traditional to modern social roles for women - beyond the setting of the post-conflict stage.