INTRODUCTION

The concern regarding the disparities between women and men in the economics profession is not new, but in the last years there has been a renewed interest in the topic, and an extended interest in this issue both in developed and developing countries. The literature has focused on identifying some stylised facts and trying to understand their underlying reasons. A common fact both in the USA and in European countries refers to the missing women in economics, as reflected by the low level of representation of women in the discipline. Strictly, time-series data regarding this topic refer to academic economists. In the USA, there has been little improvement in female representation among first-year Ph.D. students or senior undergraduate economics majors, and economics remains solidly within the lowest group in terms of female faculty shares at all levels, alongside physics, mathematics, and engineering and far below the biological and other sciences (Ferber, 1995; Lundberg & Stearns, 2019). In Europe, data regarding men and women at different stages of their academic careers also support the idea of the existence of a "leaky pipeline" which has been steady over the years, with the resulting under-representation of women among full professors (Auriol et al., 2019).

The literature has also evolved in discussing the existence of discrimination against women economists -including disparities in recruitment, salary, and promotion- and its causes and consequences. A recurring question refers to why we should worry about women being underrepresented in economics. Bayer and Rouse (2016) point out that fairness is not the only reason to worry about this: diversity within the profession ensures higher quality knowledge. As female and male economists hold different opinions and preferences concerning the role of government, the importance of labour and distributive policies, and other relevant topics, female underrepresentation may reduce the scope of the public discussion or change its focus. Based on previous behavioural evidence, they also argue that mixed gender composition in research and professional groups derives in richer interaction and better results.

The significant gaps in promotion rates for males and females in their academic careers in developed countries are in part explained by the fact that women economists publish fewer papers than men (Broder, 1993; Ductor et al., 2018; Ginther & Kahn, 2004; Hopkins et al., 2013), though the gap in publication authorship has been narrowing for recent generations (McDowell et al., 2006). This is not a specific feature of economics: for decades, multiple studies have been confirming the 'productivity puzzle' referring to fewer female-authored publications in diverse disciplines (Cole & Zuckermann, 1984; Ceci et al., 2014). Given that academic publication is especially relevant for career progress and peer recognition, the literature has focused on the research output of women and men in economics by analysing gaps in peer-reviewed publications as summarized below.

Reasons for these differences in productivity are not clear cut, but the following factors are potential prospects: i) differential academic experience related to female interruptions of low intensity due to family engagement; ii) selection of less able women in research iii) gender differences in confidence or preferences for competition; iv) gender bias in peer review; v) women dedicating more time to tasks having low promotability in detriment to research; vi) women assorting in fields with lower impact or intensity of publications vii) the role of co-author networks or team composition. These hypotheses are difficult to test because of methodological and data issues hence the discussion remains open.

The first three factors are barriers that are common to other activities in the labour market -outside the research arena-. For example, the effects of motherhood on labour market outcomes, in general, have been widely documented (Kleven et al., 2019a, 2019b), and the idea that a non-random selection in unobservable aspects (among others, ability) in certain sectors or occupations may be relevant to understanding differences in labour market outcomes is also widespread in labour economics. In our case, this may imply that less able women self-select into research as a way of avoiding strong competition pressures as economists in the private sector. Likewise, experimental evidence has reported gender differences in competitive performance and overconfidence (Gneezy & Rustichini, 2004; Larson, 2005) resulting in women shying away from competition and men embracing it (Buser et al., 2014; Niederle & Vesterlund, 2007). Although no specific evidence for researchers is available, it is reasonable to assume that these factors may operate given that academic publication involves a very competitive environment where feedback in the form of peer reviews is essential. In this context, the attitudes toward competition and the personal traits related to self-confidence may play crucial roles.

Among the potential explanations for productivity gaps that are specific to research, one line of literature has tried to understand lower female productivity in terms of research outputs considering potential gender bias in peer review. In the case of economics, no evidence was detected in a set of studies (Abrevaya & Hamer-mesh, 2012; Chari & Goldsmith-Pinkham, 2017), although recently it has been suggested that women are held to higher standards for publication in economics, using citations as a proxy for manuscript quality (Card et al., 2020; Hengel, 2020).

It has also been argued that the productivity gap may be related to differences in the allocation of time to tasks. Although we are not aware of specific evidence from economics departments, the available studies suggest that female faculty members tend to spend more hours advising students or providing service on different committees (Babcock et al., 2017; Misra et al., 2012; Mitchell & Hesli, 2013), so gender differences in the frequency of requests and the acceptance of requests for these tasks may help explain why women have a lower academic production than men.

The two other potential explanations (women classifying in fields with lower impact or intensity of publications and the role of the co-author network or team composition) are directly explored in our research. The choice of research fields may influence academic careers and publication prospects, helping to understand productivity gaps (Beneito et al., 2018; Dolado et al., 2012). Concerning networks, their crucial role in the shaping of research output may explain the different results registered for men and women (Boschini & Sjogren, 2007; Ductor et al., 2018). Given the direct connection between this literature and the hypothesis explored in our article, we further discuss its findings concerning our results. It is relevant to note that both these factors may also be related to risk-taking, personal traits, or the propensity towards competition.

Unfortunately, the discussion and the evidence concerning these issues are less widespread in developing countries and specifically in Latin America, where -to our knowledge- there are no systematic studies of gender differences in the economics profession and discipline. An exception is Uruguay in the work of Cáceres et al. (2013), who studies research in economics based on the papers presented at the Annual Economic Meetings organized by the Central Bank of Uruguay from 1986-2011. They detect the prevalence of applied research and a change in the relative importance of topics: until 1990, macroeconomic papers accounted for around 70% of all papers, whereas during the following twenty years 60% of all papers had a microeconomic approach. They also report an increased participation in female authorship.

Our contribution to the ongoing research regarding the role of women in economics is to provide both a historical perspective as well as new empirical evidence for a developing Latin American country. After analyzing the institutional and political context in which the profession of economist has developed in Uruguay, we illustrate that the country has moved from an initial female underrepresentation among economists to equal participation of men and women at present. We also provide an empirical analysis of the research output of Uruguayan economists, based on two databases, one mainly reflecting working papers and technical documents (WP) and the other including articles published in peer reviewed journals (JA). Our descriptive results demonstrate that: a) in both databases the share of female Uruguayan-resident authors increased over time; b) in WP the female share of authors, considering only Uruguayan residents, is 36% whereas in JA, it is 49%; c) men produce more journal published articles than women but there is no gender gap in working papers; d) women and men are unevenly represented throughout different fields; e) collaboration with non-local authors is more likely among men than women. Multivariate analysis shows that non-local co-authorship is strongly associated with the production gender gap.

THE ECONOMIC PROFESSION IN URUGUAY

An Overview of the Development of the Profession

Given that institutional and political contexts may shape different professional and disciplinary configurations, it is relevant to provide contextual meaning to the study of research and publication patterns among female and male economists. The boundaries within which the profession has emerged and been structured, which we discuss in this section, help to understand our original evidence regarding scholarly publications and research agendas in Uruguay. According to our hypothesis, from the 1950s through the present the development of economics as a profession in Uruguay has undergone three periods. The identification of these periods is based on three dimensions: the academic setting for the training of economists, the labour market, and role of economists in public debates.

The first period or starting point extends from 1954 to 1966. The beginning of this period is determined by the moment at which economics became a specialization within the academic curricula of the Public Accounting degree programme at Universidad de la República, the only university in the country until 1985. Until 1966, only 23 of 246 Public Accountants received their degrees with a specialization in Economics; 4 of them were women (Table 1). In the labour dimension, in the context of an interventionist state and the apex of planning strategies, the public sector was the main employer for economists. Even in this context, labour market possibilities were limited for the profession. Finally, in the arena of public debate, this period was characterized by the irruption of economists in a central role, as a consequence of the appeal and prestige gained by a newly created commission for central planning and public investment in the 1960s. This period ends in 1966 when a degree in Economics was approved and consequently, the discipline was no longer a specialization within the Public Accounting degree programme.

Table 1 Three Periods in the Development of the Economist Profession

| Starting point | Identity disputes | Expansion and global economists | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1954-1966 | 1967-1990 | 1991-2017 |

| Number of graduate economists | 23 | 397 | 2551 |

| Graduate economists per year | 4 | 17 | 69 |

| Female participation in total graduate economists | 17,4 | 21,9 | 49,3 |

Sources: based on data from Universidad de la República and Anuarios Estadísticos del Ministerio de Educación y Cultura.

The second period is characterized by identity disputes in the conception of the role of economists, extending from 1967 to 1990. The main features of this long period are economic instability and political radicalization, features shared with most Latin American countries during this period. In the specific case of Uruguay, the beginning of this period is characterized by economic stagnation and high inflation within the political context of polarization between a right-wing Administration and a left-wing guerrilla. A right-wing coup d'état took place in 1973 and economic liberalization measures were implemented in the following years. After a period of growth, a crisis hit the country as part of the well-known Latin American crisis of the 1980s. The final years of the period are marked by a return to democracy in 1985, recovery from the economic crisis, and economic stabilization.

At the beginning of the period (the end of the sixties), several leftist Uruguayan economists conceived their role as a mixture of technical and political activity, with no clear boundaries between them (Jung, 2018). This effervescence ended in 1973 when the dictatorship expelled leftist professors from the University. In 1977 and 1980 two curricula reforms were enacted, resulting in a shorter duration for the Economics degree programme, making it more similar to the programmes that prevailed in the USA. Biglasier (2002) tracks in this period the first attempts to develop a professional profile inspired on the American model, though the defence of a different profile survived in the private research centers related to the CLACSO network. With the restoration of democracy in 1985, the tension regarding the formation and role of economists emerged: some were prone to adopt international standards for professional practices, whereas others questioned that choice. The curricular reform of 1990 is in some way an expression of this unresolved tension: the duration of the undergraduate programme increased, with both the restoration of the importance of social sciences for the formation of economists and a strengthening of the quantitative pillar, by means of mathematics, statistics, and econometric courses.

On the whole, the number of economists credited with a college degree increased in a context in which the private sector gained importance as an employer. But the profession was still male-dominated: one female economist graduated for every four male economists.

The identity dispute that characterised the previous period was solved in the third period (1990 through the present) in favour of what Fourcade (2006) called the "global economist": pursuing a universal agenda, with specific methodological tools and validation criteria for professional practices which are influenced by the American model. In the third period, the growth rate for graduated economists is the highest of the entire period 1956-2017 (Figure 1). Relevant changes in the curricular arena took place. From 1995 onwards, private universities incorporated the economics degree programme into their supply of degrees and gradually became relevant actors in the production of economists. They offered a four-year programme, more inspired on the American model. In the public university, a new study plan was put in force in 2012 and the duration of the degree programme was again reduced to four years (this new plan explains the peak of the number of graduates around 2012 in Figure 1). Graduate programs were opened and the labour market for economists diversified significantly, providing a place for a wide range of professional profiles in the public and private sector, academia, international organizations, and even in the press media.

Source: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura

Figure 1 Number of Degree Graduates from Economics. 1961-2017

In this context, the orientation of Uruguayan academic economists and their ways of conceiving their activity and communicating with their peers changed. The National Agency for Research and Innovation (ANII for its initials in Spanish), created in 2008, probably constitutes a relevant landmark for researcher's careers. The agency implemented a nationwide system of subsidies for researchers and projects that has meant, besides the monetary transfer, prestige and public recognition (National System of Researchers, SNI for its initials in Spanish). The selection and promotion criteria are strongly (but not only) based on the record of publications that influenced the profile of academic economists and their efforts towards peer-reviewed publication.

It is interesting to note that an analysis of the SNI reports a gender gap in the probability of being accepted of 7.1 percentage points detrimental to women; most of it (4.9 percentage points) can be attributed to the lower academic achievements of women (Bukstein & Gandelman, 2019). But the gender gap in the probability of acceptance is larger in the higher ranks of the system and the observable characteristics of women and men explain less at the top than at the bottom of the SNI, which is consistent with the idea of a glass ceiling in an academic career in Uruguay. This glass ceiling is present in the three areas where women are most active (health-related sciences, natural sciences, and humanities), but no evidence is found for social sciences (where economics is included), agricultural sciences, or engineering.

A Gendered Picture of Economic Professionals and Academic Staff

As discussed above, the representation of women in the discipline has increased from around 15% of the total graduates in economics at the beginning of the 60s, to around 48% in the last five years. Interestingly, women are more likely to attend a public university than men. Indeed, in the last five years, females accounted for 50% of graduates from public universities and 37% from private ones (figure 2). In their analysis of several Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico), Lora and Ñopo (2009) find that women represent between 30 and 40% of undergraduate economics students, except in Colombia where they reach 60%. The authors also state that in all the countries considered, the female share is higher at public universities when compared to private ones, as detected in Uruguay.

Two facts regarding this Uruguayan data are relevant for discussion. First, contrary to what occurs in developed countries and the Latin American countries with available data, nowadays the economics profession does not attract fewer women than men in Uruguay. For the USA, studies report between 28 and 35% of women with a bachelor's degree in economics, whereas for the UK female undergraduate students of economics were around 30% in 2013, and in Spain, 36% in 2017 (Beneito et al., 2018). Second, at present, women account for around 68% of all graduates when all careers at the Universidad de la República are considered, so economics is not a feminized career when compared to others in Uruguay. For example, the situation in sociology resembles that of the entire University (with 68% women) and presents a rather stable pattern over the last three decades.

Progress in terms of female representation among economists is also reflected in the female share of faculty staff. Women teaching core courses of the economics degree programme offered by the Universidad de la República accounted for 25% of the staff in the 1980s and 44% in the period 2010-2019, with lower shares at the top than at entrance levels. In 2019, the 9 institutions that researched economics in the country employed 163 researchers. The staff was composed of 56% men and 44% women. Women were 53% of the junior researchers but 37% at the senior level. Unfortunately, we lack longitudinal data describing the trajectory of these researchers, so we can only register the existing differences.

Thus, although there has been progress for women in terms of their professional and academic participation along with the development of the discipline of economics, differences prevail for the top positions in teaching and research careers. In the following sections, we explore how these patterns translate when we consider research publications and agenda.

DATA AND METHODS

Construction of Databases

Our analysis of published output utilizes two bibliographic databases, which we briefly present in the following paragraphs; more details concerning their construction are available upon request.

The first database was conceived by the Department of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, Universidad de la República in 2004, to facilitate bibliographical references reflecting the research of Uruguayan economists. Online bibliographical repositories were unusual at that time, so existing documents were scattered throughout different libraries. The general selection criterium was the inclusion of documents presented in Uruguayan congresses on economics and/or written by authors affiliated with Uruguayan economic research institutions. It mainly contains working papers and technical documents and will be denominated WP from now on.

After a thorough analysis of the records in this repository, we maintained 814 records representing the written academic production rendered between 1986 and 2004 in Uruguay.1 All records include title, year of publication, name of authors, and abstracts. We used the first names to gender codify the authors manually.

Additionally, we employed the JEL classification code provided by the authors. In cases in which the record was missing or the information corresponded to the old JEL classification code, we manually registered a code based on the abstract. Finally, we codified authors as local or non-local individuals. We defined a local author when she/he is affiliated to a Uruguayan institution in the year of her/his publication, except in the case of students living abroad who returned after that stage and who were always considered local authors. This task was carried out on a case-by-case basis using all possible sources. The WP database involves 145 local female authors, 254 local male authors, and 49 non-local authors.

The second database utilizes free access information from the ANII online bibliographical portal (Timbó). This platform allows access to scientific and technological literature published on platforms such as Jstor, Scopus, EBSCO, Springer, Scielo, Directory of Open Access Journals, among others, which have different journalistic coverage. We identified the academic production of Uruguayan researchers, taking into consideration all current active researchers from the main academic institutions in Uruguay and all local authors of WP; we added all their co-authors whose research focuses on economics. The obtained bibliographic database reports the year of publication, names, and abstracts. As with the WP database, authors were manually gender-coded on the basis of their first name, JEL codes were ascribed on the basis of abstracts and the local/non-local condition was assigned on a case-by-case basis. This second database contains 604 journal articles published between 1984 and 2019 and will be denominated JA from now on. These publications involve 117 local female authors, 121 local male authors and 221 non-local authors. Also, there are 63 local co-authors included whose main focus is not economics and who were not included in our analysis below. It is relevant to acknowledge that in our research, every publication in the JA database is counted equally, and differences in publications in terms of quality are not considered. This obeys the difficulties faced in finding a consensual indicator to measure scientific quality and/or the impact of publications from a developing country.

Databases differ in the coverage period; JA better reflects the most recent years. Besides, JA collects peer-reviewed publications but WP consists basically of the first versions of written documents in which the final version will not eventually end up in JA (because it is a consultancy or technical report, the document is published as a book or ends up being a working paper, etc.). Moreover, WP includes documents by economists that are not subject to academic rules (for example, professionals of the Central Bank or advisors from the private sector) whereas JA reflects research production.

Both databases secure an increase of documents (though there has been a recent downturn in recent years in JA), authors, and female share over time (Figure 3 and Table 2).

The number of documents in WP increased significantly after 1996. But JA reflects that peer reviewed publications were almost an exception for Uruguayan economists until 2000. From then on, a significant increase in this type of publication took place. We argue that, in line with the new profile of economists, Uruguayan researchers were affected by the globally permeable nature of professional boundaries. Thus, the evaluation of researchers, which used to consider working papers and conference attendance, began to be based on international standards, prioritizing peer-reviewed publications.

A relevant difference between these databases refers to the composition of authorship. The female share in local authorship is 36% in WP and 49% in JA. Another interesting fact is that non-local authors are much more important in JA than in WP: indeed, in JA there is almost 1 non-local author for each local author (Table 2). We construe that networks with non-local authors are more important in JA than in WP given the more prevalent academic nature of JA.

Empirical Strategy

As discussed in the literature, determining the "gender" of a paper is not a straightforward affair. For the descriptive analysis, we considered three bibliometric indicators used to analyse publications produced by co-operation among authors of different genders: participation, contribution, and count index (Kretschmer et al., 2012). In the three indicators, the unit of analysis is the document.

Participation enumerates the number of publications with at least one author of a given gender. Denoting the bibliographic reference as r (r = 1,.. .,R), author as a (a = i,.. .,A), gender as g (g = 1,2), the condition of being an author as I (I = 1 if the condition holds and 0 if it does not), the participation of gender g in the publication Pr g and the participation of gender in the database Pg are:

The contribution index measures the share of each gender in the production of a publication assuming that each author contributed the same amount. The contribution of gender g (Crg) to one publication and the average contribution of gender g in the database (Cg) are:

The count index considers the number of authors of a given gender in each publication. The count index of gender g in a publication (Trg) and the database (Tg) are:

Note that the count index of gender g in the database is higher than the number of authors of gender g because each author is counted each time that he/she appears in a document. We calculated the female share based on the count index, dividing the total female count by the sum of the total female and male count.

Finally, we carry out multivariate analysis to analyse the gender gap in production. This econometric analysis only considers publications from our JA database, as it reflects academic publishing according to present standards. Based on our original JA database, we built a new database where the unit of analysis consists of authors included in the original JA database. For each author, the database reports the number of articles, gender, year of first publication, and several indicators of his/her main research field, non-local partnership, and composition teams. In the econometric estimations, the analysis unit is the author, and the dependent variable is the number of the authors' publications. As the dependent variable takes on positive values, we estimate a count model. We assume that the dependent variable is over-dispersed (the number of variance of documents is larger than its mean) hence a negative binomial regression model is estimated. The negative binomial distribution is a form of Poisson distribution in which the distribution's parameter is itself considered a random variable. The estimation of the dispersion parameter allows testing if it is equal to zero, that is if it is more appropriate to assume a negative binomial than a Poisson distribution (which is based on the restrictive assumption of equidispersion). We report the estimated coefficients, the average marginal effect, and the marginal effect at means of the explanatory gender dummy variable.

RESULTS

Participation, Contribution, and Productivity

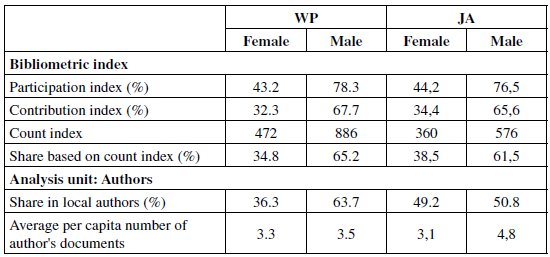

To analyse the role of female and male economists in written production we calculated indicators on the basis of local teams. As reported in Table 3, female authors are 36% of the local authors in WP and the three bibliometric indicators (participation, contribution, and share-based on count index) are lower for females and consistent with the lower share of females among local authors. The analysis based on JA yields similar results. The three bibliometric indicators are lower for females than for males, but in this database the female share is 49% of the local authors. Indeed, they participate in 44% of articles (Pg in equation 1), contribute to 34% of local teams' research production (Cg in equation 2), and account for 39% of local authorships (Tg in equation 3 expressed as a share). Thus, the bibliometric indicators for JA suggest a less important female role in production than indicated by their share in authorship.

This overall picture is reflected in the average per capita number of documents by gender. There is no gender difference in WP at usual statistical significance levels (with an average production of 3.4 documents per author considering all the documents in the database) but male production is significantly higher than female production in JA. Indeed, women in the JA database register on average 3.1 per capita articles and men, 4.8. We reject the hypothesis that this difference is null with a p-value equal to 0.026. The lower number of publications of female economists in peer-reviewed articles is consistent with previous evidence related to developed countries (Ductor et al., 2018; Ginther & Kahn, 2004; Hopkins et al. 2013; Lund-berg & Stearns, 2019).

We interpret differences in results between the two databases as a consequence of their different natures. As mentioned, WP includes not only academic production but all type of documents, whereas JA only contains peer-reviewed articles. In synopsis, a gender gap is not present in the written production of economists but women write less academic journal articles than men. We may speculate with regards to the reasons for this result. One possible explanation is that the academic environment, and more specifically journal publication, is a more competitive arena and men adapt better than women to these conditions. Another possible explanation is that self-selection into the academic and non-academic sectors is not gender-neutral, particularly in a country in which most academic positions are located in the public sector. We may speculate that positions suitable for economists in the private sector are more likely subject to gender discrimination than positions in the public academic sector. Under this scenario, private sector female economists may be selected among the pool of the ablest candidates. To delve deeper into this explanation we analyse the grades of 24% of JA authors. We do not find a statistically significant gender gap with regards to grades, which suggests that this is not a source of gender differences in publishing.

Leaving aside the relevant discussion on how productivity should be measured throughout scientific careers, it is important to note that evidence for the developed world indicates that women tend to adopt publication strategies more focused on producing books or book chapters (see Mayer & Rathmann, 2018 for psychology and Davis et al., 2001 for economics). This implies that the study of research products based on articles may be non-gender neutral, even acknowledging that journal articles play a dominant role in the publications of economists. Based on the information provided by CVs uploaded onto the web page of the SNI, we calculated the average number of published journal articles, book chapters, and books by researchers in economics. Over the entire period registered in their CV, the average number of publications per woman is 9.0 journal articles, 5.2 book chapters, and 2.5 books. For men, these numbers are 13.2, 4.9, and 1.6, respectively. Note that if we give the same weight to each type of publication, the average number of published documents remains higher for men (19.7) when compared to women (16.7).

Given the important role of journal article publications in career promotion, the strategy of women remains a puzzle to be understood. Two additional factors related to gender gaps in academic production are explored in this paper. One is the potential gender gap in field selection and the other is the importance of team composition. The following subsections address these issues, and then we provide a multivariate analysis in an effort to disentangle the role of each factor.

Gender Distribution Across Research Fields

If there is gender segregation by research field, different standards of publication requirements among fields may contribute to explaining the gender gap in publication. A challenging methodological problem related to this issue is the causality between uneven gender distribution by research fields and production gender gaps. Do women produce less than men because of the field of concentration or do women select fields with high-standard requirements for publication? In any case, the research field of an author may influence her academic career and may be relevant to understanding women's performance in economics.

To explore gender segregation by research field among Uruguayan economists we consider the classification of documents by 1-digit JEL codes; a document with two JEL codes is counted in both fields. Female shares based on the count index (Tg in equation 3) in each field are presented in Figure 4. Results are similar between both databases but overlapping is not complete. Using WP, the research fields where the female share is above the average are Labour and Demographic Economics, Industrial Organization, Health Education and Welfare, and Economic History. In the case of JA, the three most feminized research areas are Labour and Demographic Economics, Health Education and Welfare, and Public Economics. In these three cases, the female share is between 50 and 60% whereas the average female share is 38%. JA also reflects that academic production in the areas of Financial Economics and Mathematical, Agricultural Economics and Quantitative Methods is male-dominated in Uruguay. Similar patterns were found under the contribution index (Cg in equation 2). This pattern of gender segregation by research fields in Uruguayan academic research had already been noticed by Cáceres et al. (2013) based on presentations in Uruguayan congresses in the period 1986-2011 and is consistent with international findings.

In effect, Dolado et al. (2012) find that European female researchers concentrate on Health, Education, and Welfare, and Labour and Demographic Economics (with a share of 25%) while Mathematical Economics, Agricultural Economics, Other Special Topics, and School of Economic Thought are the least popular fields among women (less than 10%). The authors argue that female academic economists may avoid male-dominated fields to elude mixed-gender competition -in line with the arguments of Gneezy and Rustichini (2004) regarding gender differences in the propensity towards competition-.

Boschini and Sjögren (2007) analyse top journals and conclude that the highest participation of women (around 20%) is observed in Health, Education and Welfare and Labour and Demography whereas the lowest (less than 10%) corresponds to Financial Economics and Macro and Monetary Economics. Based on conference programs at the NBER Summer Institute, Chari and Goldsmith-Pinkham (2017) find that the share of women in Microeconomics programmes is almost 26% whereas it is 16% in Macro and International Economics and 14% in Finance. Considering meetings of AEA, Beneito et al. (2018) also find a higher presence of women in research topics in microeconomics; interestingly, they also provide evidence that this gender-based inclination towards specific subfields in economics appears at the undergraduate level. On the basis of doctoral dissertations from the USA, Lundberg and Stearns (2019) provide evidence that women are more likely than men to study topics in Labour and Public Economics and less likely to conduct research in macro and finance. They argue that this gender choice bias could be sustained over time because of differences in the research environment: a higher share of female faculty members in a field might encourage female students to choose it because of role model effects. Similarly, Carrell et al. (2010) and Bettinger and Long (2005) point out the role of mentoring as an explanation for high female segregation in certain subfields.

The above-mentioned shares indicate that segregation runs deeper in Uruguay than in Europe and the USA. We estimated the Duncan index to compare the results obtained for developed countries.2 The Duncan index is 0.29 and 0.18 when using JA and WP, respectively, whereas it ranges from 0.11 to 0.13 in the study by Dolado et al. (2012). As there is evidence regarding convergence trends in developed countries, the higher segregation level in Uruguay may be related to the relatively recent development of the discipline and the induction of women. We calculated the Duncan index for sub-periods to further consider this hypothesis. We noted a time trend in terms of gender segregation in JA: it is 0.442 before 2008 and 0.275 when considering the last ten years. However, we are aware that the number of cases is too low to obtain robust results.

Team Composition

Given that research is a collaborative activity and that feedback from peers is crucial for the quality of work, collaboration between individuals may be a relevant aspect in understanding academic performance. The role of co-authorship networks and the composition of the research team has been widely analysed in the specialised literature. The increasing trend in co-authorship in economics has been observed by Hamermesh and Oster (2002) and Card and Della Vigna (2013), among others. In this context, if there is gender sorting in team formation, the probability of finding "good coauthors" is less for the minority gender, and this may affect its productivity.

Given our condition of as a developing country with a high migration incidence of the highly-educated population, collaboration with non-local researchers or technicians stands out as a significant feature. Partnership with non-local authors has potentially positive effects on the productivity of local authors. Indeed, it provides training in the development of publishing-related skills which are particularly important in a context where publication in international academic journals is relatively recent. In sum, systematic gender differences in the likelihood of non-local partnership, such as the ones detected, may affect (and eventually reinforce) gender gaps in academic production originated in other factors. Previous evidence suggests that networks are relevant for the understanding of gender gaps in production. Ductor et al. (2018), who find significant gender differences in research output, link this gap to gender differences in network structure. Their results show that women have a higher share of co-authored work, co-author more with senior colleagues, tend to have fewer co-authors than men and exhibit greater overlapping among their co-authors. After control of these network indicators, gender gaps in output decline, but they do not disappear. Based on circumstantial evidence, the authors argue that women -as a consequence of preferences or environmental factors- make less risky choices with regards to academic collaboration, resulting in lower academic output. Given the importance of international networks in the Uruguayan case, the role of this type of partnership deserves a closer look.

In Table 4 we present information about non-local partnerships using the author as the unit of analysis. According to WP, around 10% of local authors have written production with non-local authors and there is no statistically significant gender gap in this probability (Table 4). But JA shows different results, the nonlocal partnership incidence is notoriously higher (37%) and the gap between men and women is statistically significant. Indeed, 45% of the men and 30% of the women co-authored at least once with a non-local researcher. Within this group, the non-local count index is higher for men than for women within these groups. Moreover, and consistently within the group, the share of articles produced with non-local researchers is higher among men than women. In brief, all the indicators show that non-local partnership is more likely among men than women.

Table 4 Non-local Author's Partnership

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1 for a test of means (proportion) testing the null hypothesis that female-group is equal to male-group.

Source: Authors based on WP and JA

JA reflects that researchers who have at least one non-local partnership in their empirical publication life have published more articles than researchers who never have had a local partnership (Table 4). This holds even when we compare exclusively the number of articles written by local teams. We do not know the source of this difference but there are at least two plausible explanations. First, if networks increase with age, it is possible that the group of researchers without non-local partnerships are younger and subsequently, have a still lower number of publications. Second, as already mentioned, productivity may be positively correlated with non-local partnership whatever the causal relationship may be.

Finally, we use JA to analyse the country of origin of journals in which academic production is published. European and Latin American journals are the most frequent destination of articles (Table 5). But the importance of the destination varies depending on whether there is a non-local author or not. Latin American journals take account of 53% of articles when written only by local authors; this share declines to 36% for European journals and is only 10% for those published in the USA. In the case of non-local partnerships, the share of Latin American journals falls to 22% whereas the share of European and American journals increases to 55% and 23%, respectively. Because there is a non-local partnership gender gap, we may expect gender differences in the geographical destination area of articles. Indeed, female authors are more likely than male authors to publish in Latin American journals but the magnitude of the gap is slight.

Estimation of the Production Gender Gap

To explore the potential explanations for the gender gap in journal articles, we perform a multivariate analysis using the JA database. The observations are the local authors and the dependent variable is the number of publications registered in the database. Under all specifications, the negative binomial model is preferred to the Poisson estimation, suggesting the prevalence of the zero-dispersion parameter. Our main results are displayed in Table 6.3

Table 6 Negative Binomial Estimation Results. Dependent Variable: Number of Documents.

Source: Authors based on JA

In column (1) we report the results of an estimation in which the only independent variable is a female dummy variable that takes value 1 for women and 0 for men; the marginal effect of this variable captures the raw gender difference in the number of articles, resulting in a coefficient of 1.7 in favor of men. In column (2) we include the author's first year of publication. As expected, the estimated coefficient of this variable is negative: recent authors are probably younger and are just beginning their academic life, so their number of publications is lower. The introduction of the author's first year of publication reduces the female marginal effect, consistent with their later entry into the economic discipline and the academic labor market. Thus, part of the gender gap may reflect the fact that we are not able to observe the true complete periods of academic life, and given the belated female incorporation, we observe shorter periods of academic life for women than for men.

In column (3) we introduce the female proportion in the author's main field, defined as the most frequent JEL within the articles produced by the author. The sign of the estimated coefficient is positive indicating that publication is higher in more feminized subfields. This result holds even when the female dummy variable is not included. Thus, the marginal effect of the female variable widens for column (2). However, we are aware that the field variable is not exogenous because women may choose the specialization field based on the ease or difficulty of evolving within it. In any case, we argue that, subsequent to controlling for potential differences in publication across fields, the gender gap in journal article production remains.

In column (4) we attempt to control for partnership with non-local authors. Specifically, for each author, we calculate his/her number of non-local co-authors per article and we include this variable in the estimation. The estimated parameter is positive. We also include the interaction of this variable with the female dummy. We obtain a positive coefficient but we cannot reject that it is null. Once again, we have to be cautious in the interpretation of the ratio between non-local partnership and productivity, as unobservable abilities may increase both the likelihood of publishing and partnering with non-local researchers. However, we may speculate that production increases with the non-local partnership due to the beneficial effect of the enlargement of productivity networks. The most interesting result is the reduction of the effect of the female dummy variable: the average marginal effect of the female dummy variable declines from -1.857 in column (3) to -1.310 in column (4). Thus, we may construe that non-local partnership plays a role in the gender production gap.

We finally control the estimation using the proportion of articles that were written by a gender-mixed local team and its interaction with being female. As reported in column (5) the estimated coefficient of the first variable is negative and the second one is positive but neither of them is statistically significant. The marginal effects of being female reduce slightly the ones obtained in column (4).

We carried out several robustness checks, estimating the average marginal effect and the marginal effect by means of the female dummy variable for each alternative specification. First, we introduced the main field's authors by means of a set of dummy variables instead of the proportion of women in the field. As we may see in Table 7, results regarding the gender gap become weaker under this specification.

Table 7 Robustness Checks. Average Marginal Effect and Marginal Effect at Means of the Female Dummy Variable.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1

Source: based on JA

We also tested alternative indicators of non-local partnership. As in the main results, the effect of the female dummy variable declines in relation to the raw gender gap when the alternative variable is a dummy variable that distinguishes whether or not the author has at least one article with a non-local author. This conclusion also holds when the role of non-local partnership is measured as the ratio of the count index of non-local authors to the count index of total authors, and as the ratio of articles written with non-local authors to total articles. We also used the count index of non-local authors as a proxy of non-local partnership: in this case, we cannot reject that the effect of the female dummy variable is null at the usual statistically significant levels. However, this variable is sensitive to the number of articles so we must be cautious when interpreting this result. In synopsis, our conclusion that non-local partnership contributes to the explanation of the gender gap in publishing is robust once different ways to measure it are tested.

We also carried out a robustness check using a sub-sample of authors. We eliminated authors with production over and above the 9th decile of per author article distribution (30 or more articles). At this juncture the raw gender gap is close to 1.3 articles, capturing that the "super-producers" are more likely men. However, the average marginal effect and the marginal effect at means of the female variable in the complete specification remain non-significant, confirming our previous results. If we exclude the "super-producers", the gender gap in production disappears once we control for production with non-local authors.

Finally, we estimated a (left-censored) Tobit model in which the dependent variable is the number of documents weighed by contribution (measured as the share of the author in total authors). We arrive at the same conclusions as the ones reported above. Indeed, the marginal effects of the female dummy diminish when we introduce all the covariates. Moreover, the effect loses statistical significance due to the inclusion of collaboration with non-local authors.

FINAL COMMENTS

Since 1954, when the economics profession was conceived as a discipline with its own academic curricula, the representation of women has increased slowly but steadily. Nowadays women are as attracted as males to the discipline of economics, and the levels of female participation are higher than those observed in other Latin American and developed countries. The reasons for this peculiarity merit attention in future studies of the discipline. However, economics is not a feminized career when compared to other disciplines in Uruguay.

Our analysis regarding research production in economics shows that female and male-dominated subfields are similar to the ones reported for developed countries, but the segregation index by subfields is notoriously higher in Uruguay. The links between segregation in economics in developed countries and countries with a later development of the discipline, such as Uruguay, remain an open question for future research.

Our main results reflect that men produce more journal articles than women but there is no gender difference in the production of working papers and technical documents. A relevant feature of Uruguayan research production in economics is the high contribution of non-local authors, especially in the case of journal articles. Partnership with non-local authors is more likely among men than women and is positively correlated with the production of journal articles. The fact that international networks and co-authorships impact the probability of publishing and that there are gender differences regarding their access is relevant for the design of public policies to foster and support academic research. The reasons for lower female partnership with non-local authors need to be further explored to better inform policies. Does international collaboration imply a higher burden for women? Is the lower probability of non-local partnership for females associated with personality traits or preferences, or is it productivity-based? Does the male-dominated nature of economics at the world level explain this unequal distribution of international collaborations between men and women? Academic interactions and resulting networks can be shaped by institutions to broaden the opportunities for Uruguayan researchers, and especially for women.

Two other avenues for further research on this topic can be identified. First, both at the international level and in Uruguay, women tend to adopt publication strategies more focused on producing books or book chapters than peer-reviewed articles. Understanding the reasons behind these strategies is important for the discussion on how productivity or performance should be measured throughout scientific careers, a crucial aspect in the design of policies to strengthen national research systems in developed countries. Second, our analysis does not consider the quality of the publications. The relatively recent expansion of peer-reviewed publications in Uruguay and the ongoing debate concerning the adequate metrics for publication-quality are complexities to face in order to progress in this line of research, which may shed more light on the nature of gender gaps in academic production.