INTRODUCTION

In 2020, the COVID-19 crisis highlighted the need for increased state spending to contain the advance of the virus and alleviate the economic effects of the pandemic. An unprecedented space was opened for the discussion of more heterodox approaches and policies in the international arena. Not even the 2008 crisis shook the dominant theoretical framework to the point of mainstream economists suggesting, as at present, that we are experiencing a 'New Fiscal Consensus'1 (Blanchard et al., 2021; Sandbu, 2021).

While 'conventional macroeconomic theory is in crisis,' Modern Money Theory (MMT) is one of the alternative approaches that is commonly referred to (Deos et al., 2021; Wray, 2020). MMT authors dedicate efforts to demystifying economic ideas and concepts entrenched in society by the mainstream, offering a new basis for economic policy and the action of the state. Such efforts are not new, but the crisis in the mainstream is opening room for conceiving new forms of thinking about the economy. In particular, MMT highlights the importance of fiscal policy for the well-functioning of the economic system, especially for bringing the economy closer to full employment and meeting social demands.

The application of the MMT framework to design economic policies for developed countries -e.g., the adoption of principles of functional finance- is more established in heterodox literature. Especially when dealing with the United States, which issues the global currency and benefits from this 'exorbitant privilege.' However, when dealing with developing countries, some authors such as Wray (2019) associate the applicability of MMT principles to the adoption of flexible exchange rate regimes, while others such as Vernengo and Caldentey (2020) and Kregel (2021) acknowledge that jurisdictions that issue sovereign currency cannot default on their own currency, though they can default in foreign currency, and with this, fiscal policy would be subject to several restrictions. In turn, Prates (2020) resorts to the idea of policy space of emerging economies as a post-Keynesian alternative, being determined by the degree of monetary sovereignty and a country's position in the international currency hierarchy.

In this paper, we develop an empirical analysis of the applicability of MMT to Brazil. Given the country's conjuncture of stagflation and the growing needs of the Brazilian population, it is essential to fuel the economic debate with new ideas and solutions that go beyond austerity policies and interest rate hikes. We consider that it is of paramount importance to understand whether the arrangement proposed by MMT, originally conceived in the American context, is applicable to Brazil and what limitations it might face, especially considering its condition as a peripheral country.

Therefore, this paper aims to discuss the formatting of fiscal regimes in countries that issue sovereign money based on an MMT approach and to analyse the applicability of a functional finance regime to the Brazilian case. We analyse the evolution of relevant macroeconomic variables and the institutional framework of fiscal policy in Brazil between 1999 and 2019 to assess whether it can be characterised as a sovereign currency economy and evaluate the policy space of domestic economic policy2. The underlying hypothesis to be investigated is whether MMT's economic policy prescriptions are applicable to the Brazilian case.

The methodology involves three complementary efforts. First, we make a brief review of the literature on fiscal policy in sovereign currency countries, considering the perspective of the periphery, taking into account both MMT and recent mainstream contributions. Second, we provide an empirical assessment of macroeconomic indicators associated with the characterisation of Brazilian economic policy autonomy during the period 1999 to 2019. Third, we map how the current fiscal policy framework in Brazil is structured based on primary (legislation and complementary infralegal norms), and secondary (academic literature) sources in order to understand what changes would be necessary if the country were to adopt a MMT approach.

FISCAL REGIMES IN COUNTRIES THAT ISSUE SOVEREIGN MONEY

The economic policy framework in force in Brazil since the beginning of the current century follows the orientation of the 'New Consensus in Macroeconomics' (NCM) (Oreiro & Paula, 2021). This consensus favours a monetarist perspective on inflation and views macroeconomic stability as a key ingredient for long-term economic growth. Monetary policy takes the leading role in macroeconomic stabilisation, being used to avoid deviations of production from its potential level and inflation from its target (Paula & Saraiva, 2015).

Fiscal policy is of secondary importance, as it should focus on creating conditions for stability and providing credibility -fiscal austerity- to economic authorities, serving as a beacon for the expectations of economic agents (Lopreato, 2006). Such a policy should be based on fiscal rules that 'avoid' time-inconsistency of government actions and are guided by the principle of sound finance -or, to more orthodox economists, even by the reduction of public spending and the size of the state. This set-up derives from a theory that postulates that fiscal policy is ineffective in affecting the level of income, with fiscal multipliers smaller than one (Ramey, 2019).

However, the international financial crisis of 2008-9 challenged the NCM. The ability of monetary policy to influence output in the short run was compromised, as interest rates in central countries approached zero -monetary policy became ineffective. The severity of the recession opened the possibility of countercyclical and discretionary use of fiscal policy in the short run, with the recognition that the presence of hysteresis could render fiscal adjustments self-defeating, compromising long-run economic growth and fiscal sustainability (Delong & Summers, 2012).

These changes did not imply an abandonment of the previous theoretical framework, as the European crisis itself illustrated in 2011-12 (Fiebiger & Lavoie, 2017), but they opened an important path for the development of alternatives. Even fiscal rules became more flexible, however, with the development of new institutions, such as fiscal councils to compensate for the authorities' greater (relative) discretion (Eyraud et al., 2018).

After COVID-19, the challenges to the mainstream view of fiscal policy were even more pronounced. Furman and Summers (2020) and Blanchard (2022) point to the functionality of fiscal policy as a stabilisation mechanism in contexts of low interest rates and severe recessions, even advocating for the use of new metrics -such as the ratio of real debt service to GDP- in order to assess a country's fiscal situation. Fiscal expansion would favour expenditures in public investment and in areas where the 'rate of return' on spending exceeds its costs. Other authors even point out that there is room for adopting fiscal regimes that are even more flexible than the second generation of fiscal rules in central countries (Blanchard et al., 2021; Orszag et al., 2021).

Blanchard et al. (2021) call this a 'New Fiscal Consensus,' integrated by three main propositions: (i) macroeconomic policies are necessary in order to expand aggregate demand and make it compatible with supply, since private sector demand is chronically weak; (ii) fiscal policy is the main instrument since monetary policy with low interest rates is not effective or has already had its capacity exhausted; and (iii) the fiscal space is given by a favourable trajectory of public debt, with low interest rates ensuring its sustainability.

However, the 'novelty' of this new consensus does not extend beyond the borders of developed countries. For emerging countries, the authors draw a different story:

there are still limits to how high debt can go, and these limits are tighter in EMs. Prospects for growth and interest rates are more uncertain. The scope for fiscal adjustment in the face of higher rates or lower growth is more limited. Consequently, one should be careful in importing wholesale the new fiscal consensus from advanced economies to emerging-market economies. (Blanchard et al., 2021 p. 13)

Summing up, despite the theoretical advances within the mainstream towards a less restrictive approach to fiscal policy, only under very special conditions could this 'New Fiscal Consensus' be applied to emerging countries such as Brazil. For emerging economies, balanced public budgets and debt sustainability remain the main policy goals, guided by rules that avoid discretionary policies. The effects of fiscal policy on income, employment, as well as the living conditions and dignity of the population in general are left behind.

In this paper, we present an alternative view of fiscal policy based on MMT and Lerner's functional finance paradigm. This alternative is openly critical of the NCM and shifts the objectives of fiscal policy from budget results and coordination of expectations to the reduction of inequalities, economic growth with full employment, and to concrete actions that affect the daily lives of citizens.

This alternative fiscal regime refers directly to the condition of states as issuers of sovereign currency or sovereign money -in the Brazilian case, the Real. This condition reflects how contemporary monetary systems are structured (Deos et al., 2021; Kelton, 2020). It aligns with recent MMT contributions, but seeks to highlight aspects distinct from those conventionally addressed by authors representing this tradition (Wray, 2020).

The condition of monetary sovereignty refers to the ability the state of a given jurisdiction possesses with respect to taxation and spending in a currency that it has issued. A state with monetary sovereignty taxes and spends in the currency it issues, not promising to convert it into anything the state cannot control3, as well as not going into relevant debt in a currency other than its own (Kelton, 2020, p.15).

According to Wray (2019), four characteristics must be observed. First, the state must have the ability to set the unit of account in which prices and contracts will be denominated. Second, it must be able to impose a collective obligation -for example, taxes- denominated in that unit. Therefore, since individuals are obligated to pay taxes, there is a general demand for the thing (money) that represents the unit of account. Third, the state must be able to issue the currency that represents the created unit of account and that currency is the only accepted form of payment for the taxes. Finally, the state must not undertake to convert the state currency into anything it cannot control, and it must not subject itself to a relevant foreign debt.

These characteristics would reflect the fundamental fact that money, as we know it, and with the social role it plays, is originally a creature of the state, which is configured primarily based on its role as a unit of account and its power to liquidate debts (Graeber, 2011). When the state defines which instrument it will accept as payment for taxes, it is also establishing and creating demand for its currency (Dalto et al., 2016). Furthermore, by recognising this sovereignty, the conventional budget constraint applied to governments does not occur.

In other words, the government has no financial constraints on spending, it cannot 'break' in its own currency, even though the macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy are relevant: fiscal policy should be used according to the availability of real resources in the economy, considering its effects on the level of capacity utilisation, employment, and inflation. Thus, public finances should be used in a way that is functional to the economy, promoting not only the objectives mentioned above, but also enabling an arrangement that assures citizens their fundamental rights and reduces inequalities (Lerner, 1943).

It is important to mention that, in this alternative framework, a budget result in a given fiscal year -whether a deficit, balanced, or surplus budget- cannot be considered good or bad in and of itself. It should be considered good if it provides balanced conditions for the economy as a whole and delivers the objectives defined above (Kelton, 2020). Moreover, the state does not depend directly on taxes to finance itself, but taxation has several functions: it creates demand for money, destroys money and reduces any excess of purchasing power in the hands of citizens, and is used to redistribute income and encourage or discourage certain behaviours.

Two principles should guide the government, as established by Lerner (1943): (a) it must set a level of spending that makes the aggregate effective demand compatible with full employment without causing inflation; and (b) the government may resort to issuing money, public bonds or even increasing taxation to adjust to agents' portfolio decisions, but it can always 'finance' its expenditures in sovereign currency.

The exchange rate regime and the external position of the domestic currency should be considered, since they are relevant to macroeconomic policy. The external position of a country's currency, or how much its currency is in demand internationally, can imply a restriction on the balance of payments' current account (Dalto et al., 2016, p. 145). Thus, one must be aware of the fact that countries have different degrees of monetary sovereignty: a higher degree is desirable because it means that the country has more autonomy in adopting certain types of policy, mainly regarding interest rates (Kelton, 2020, p. 69).

The short-term basic interest rate of the economy is a policy decision, established institutionally and exogenously by the monetary authority4, which pursues different ultimate goals, such as inflation targets, full employment and the stability of the financial system (Serrano & Summa, 2013). However, the fact that the monetary authority determines the basic interest rate and indirectly influences the long-term interest rate does not necessarily mean that it can set any level for the interest rate, especially in the case of peripheral countries.

Vernengo and Caldentey (2020) note that the need to obtain foreign currency can restrict the scope for peripheral countries to act. Since they are usually more dependent on their imports, especially for intermediate and capital goods (which are essential for economic growth), they end up with a need to obtain foreign currency to finance imports and therefore with a more restricted policy space. In addition, the higher the external debt of the country, the higher the demand for foreign currency, considering that the debt service will also be higher, as will the perception of risk.

In other words, developing countries that issue sovereign currency cannot default on their own currency, regardless of the exchange rate regime adopted. However, they can default in foreign currency, and in this case, fiscal policy would not be unrestricted5: a current account deficit that cannot be financed, either because of a capital outflow or because of a loss of reserves, may force the government to conduct a contractionary fiscal policy in order to reduce imports and the external imbalance (Kregel, 2021; Vernengo & Caldentey, 2020; Vergnhanini & De Conti, 2017).

Regardless of the real constraint and the balance of payments constraint, fiscal policy in this regime assumes the role of protagonist, being actively used to bring the economy to full employment and ensure other socially desirable objectives. In the following section we will assess the degree of Brazilian monetary sovereignty in the period 1999 to 2019 in order to subsequently discuss the feasibility of establishing a fiscal regime with the objectives outlined in this section.

MONETARY SOVEREIGNTY AND POLICY SPACE IN BRAZIL: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS FROM 1999 TO 2019

To what extent can Brazil, a peripheral country, be considered a sovereign currency country? What degrees of freedom does it have in determining its fiscal policy? In this section we will empirically assess the conditions of Brazilian external and internal indebtedness. In the past, the Brazilian economy has experienced major difficulties in foreign currency financing, with emphasis on the foreign debt crisis during the so-called 'lost decade' in the 1980s.

Since the adoption of the real, Brazil has met the basic characteristics of a country with sovereign money: the government sets the unit of account in which prices and contracts are denominated and taxes and issues debt and money according to this unit. However, the condition of foreign currency indebtedness has varied over time, so that the degree of economic policy autonomy continues to depend on external constraint conditions.

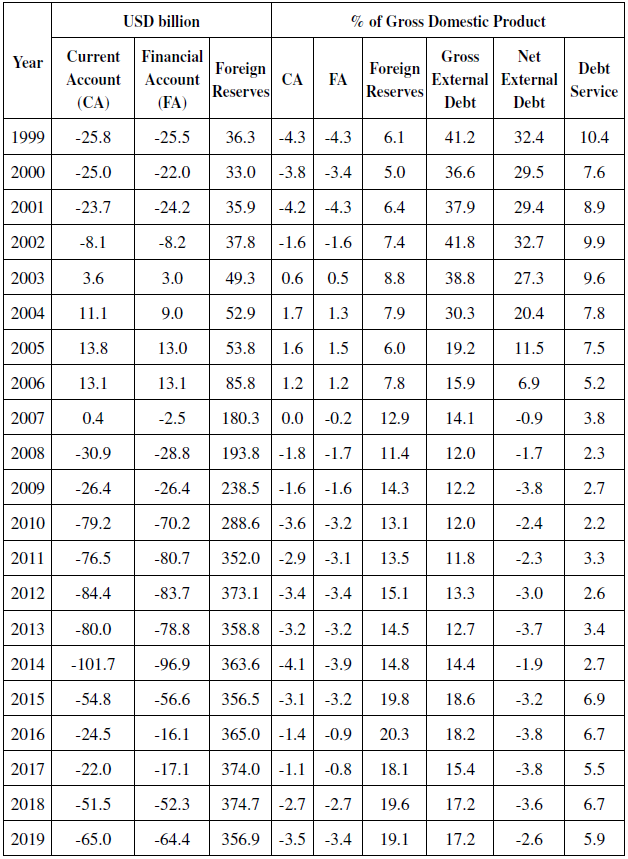

Table 1 shows a set of external indicators of the Brazilian economy. The current account balance, used in the literature as a basic measure of external constraint, showed positive values only between 2003 and 2007, before the international financial crisis, which indicates that Brazil still needs the inflow of foreign capital to obtain a surplus in the balance of payments. However, this does not necessarily mean that the Brazilian economy is continuously indebted in dollars.

In fact, the evolution of the stock of the external public debt in gross terms, a variable that is very sensitive to the exchange rate, does not indicate a greater dependence of the country on foreign currency. Table 1 shows a long-term downward trajectory of the indicator, which goes from 41.2% in 1999 to 17.2% of the GDP in 2019 -with a minimum of 11.8% in 2013. Net external debt, in turn, corresponds to the gross external debt minus the investments in foreign currency. We can see that it also showed a declining trajectory and, in 2007, the net external debt as percentage of GDP becomes negative, indicating that Brazil has reverted its external position, becoming a net creditor in foreign currency -a situation that persists until today. The accumulation of international reserves in that period provided an external cushion for the Brazilian economy.

International reserves are relevant for peripheral countries, as they provide more room to maneuver for domestic policies and alleviate possible external restrictions faced by the country6. As Brazil adopts a floating exchange rate regime, this high level of reserves allows the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) to avoid abrupt volatility in the foreign exchange rate. From the point of view of the Brazilian state, the position of (net) external creditor indicates a lower need to obtain a currency it does not issue, in theory conferring more policy space to Brazilian authorities.

The reduction in the weight of foreign exchange-indexed securities in the total composition of government debt reflects the easing of external restrictions. Figure 1 shows this reduction in the share of exchange-indexed securities in the total public debt, especially between 2004 and 2011. After that, this share remained below 5% for most of the period. Considering the data analysed, we may conclude that, unlike the past, the last decades have been marked by important changes that have resulted in the fact that the Brazilian government does not incur in significant foreign currency debt and that the public debt is not indexed to the behaviour of the exchange rate.

Source: National Treasury.

Figure 1 Percentage of Public Debt Indexed to the Foreign Exchange Rate 2004-2019 (%)

In other words, from the point of view of the external constraint, the high level of international reserves obtained through a deliberate strategy of accumulating dollars gives the Brazilian government some room to maneuver in terms of political autonomy. An important aspect of this autonomy has to do with the definition of interest rates: the government has the capacity to set the interest rate with relative autonomy, but it cannot set it at any level. As discussed in the previous section, there is an international hierarchy of currencies. For most peripheral countries, including Brazil, there is a floor for domestic interest rates, which, in simplified form, is given by the sum of the US interest rate, the country risk and the expectation of exchange rate devaluation (Jorge, 2020). In this sense, Brazil has degrees of freedom and room to maneuver, but does not have full autonomy like the US government and the central bank.

This relative autonomy in the external front is related in parallel to the internal debt dynamics of the Brazilian state. Brazil has never gone through a formal dollarisation process in its contemporary history, but it has had difficulties in placing assets denominated in local currency -which, for example, fostered the need for an 'indexed currency,' or indexed debt, during the period of high inflation. However, the reality of the Brazilian economy today meets the basic conditions of a sovereign currency economy:

given the Brazilian institutionality and the unique role played by the government debt in wealth allocation by the private sector, the government will always be able to pay for goods, services, and its maturing debt denominated in its own currency, and therefore, there is no risk of default in sovereign debt. The role of Central Bank purchasing Treasury debt in the secondary market provides infinite liquidity for it. This fact, reinforced by the Primary Dealer System, guarantees an elastic demand for primary auctions. (Jorge, 2020, p. 50)

There are institutional aspects that confer degrees of freedom to the National Treasury and ensure that it has more bargaining power in the public debt market than the private sector. The Treasury cannot be held 'hostage' by the market in the sense that the Treasury has the flexibility to adjust its bond issuing strategy according to its Annual Borrowing Plan. The authority is free to adjust what had been previously planned for the year in relation to auction dates, the securities to be traded, their maturities and the total volume of issuances. That is, it observes the economic conjuncture and market conditions and may decide to hold auctions that were not foreseen, or not to hold the foreseen auctions, or even hold them, but not accept any offer, usually with the purpose of avoiding an increase in the cost of public debt (Jorge, 2020, pp. 50-51). This flexibility has evolved pari passu with the liquidity reserve -the 'debt cushion' -, which consists of funds deposited in the Treasury's account at the Central Bank of Brazil- the so-called Treasury's Single Account.

Jorge (2020) presents evidence that, in recent years, the Treasury did not suffer any kind of veto on the issue of its securities or undergo any persistent upward pressure on interest rates, managing to successfully hold its auctions. The 'bond vigilantes' argument does not hold up. Not even the downgrades in risk classification that the country experienced, with the loss of its rating as investment grade, were capable of creating pressures or persistent changes in the auction rates or in the quantity of bonds sold. Yet, neither has the increase in the domestic public debt (Figure 2) implied any major change in the Treasury's ability to conduct its debt-financing operations.

Source: Central Bank of Brazil.

Figure 2 General Government Gross Debt (GGGD) and Public Sector's Net Debt (PSND) as a share of the GDP 2001-2019 (%)

Figure 3, in turn, employs Jorge's (2020) methodology to evaluate the success of auctions. This indicator analyses the primary auctions of the National Treasury during the 2000s and compares the quantity of public securities sold in relation to the quantity offered by the Treasury. It is a proxy of market 'acceptance' of Treasury auctions and a measure of how 'easy' is to issue new debt by the Treasury. Figure 3 also plots the behaviour of indebtedness, in order to show that the increase in public debt in recent years did not jeopardise the Treasury's capacity to issue public securities.

Source: Jorge (2020) and author's elaboration based on data from the National Treasury.

Figure 3 General Government Gross Debt over GDP and the Percentage of Public Bonds Sold in Treasury Auctions 2000-2019 (%)

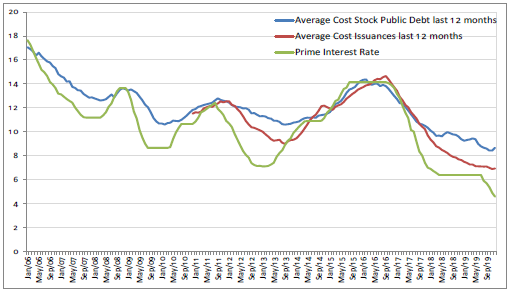

Our data suggests that there was no market rejection of bonds as a result of the increase in public debt, since the quantity of securities sold in relation to the total offered increased even with the increase in the stock of public debt as a proportion of the GDP as of 2014. Moreover, the volume sold during this period was higher than that registered between 2002 and 2013, when the debt/GDP ratio was in decline. Added to this is the fact that the average cost of debt did not increase proportionally to the increase in debt. The Treasury increased the quantity of new issues and the average cost followed the trajectory of the prime interest rate regardless of debt growth (Figure 4).

Source: Central Bank of Brazil and National Treasury.

Figure 4 Average Cost of the Stock of Public Debt and Issuances in the Last 12 months and Prime Interest Rate 2006-2019 (% a.a.)

Another relevant issue is the profile of Brazilian domestic debt. It is generally accepted that public debt is rather concentrated in short-term and floating-rate bonds in Brazil. Many economists argue that this is an undesirable feature (Brito et al., 2019), reflecting negative characteristics of the Brazilian government bond market and the existence of 'bond vigilantes,' which generate upward pressures on interest rates and prevent an increase in the maturity of public debt. Jorge (2020) sustains the debt profile is not as relevant as it appears to be in the economic debate, because the government will always be able to intervene in the public bonds market, especially to ensure its stability. Even with a debt with a long-term profile and pre-fixed rates, in times of adversity and greater uncertainty, investors tend to exchange such assets for short-term bonds with floating rates. In addition, the cost of public debt is more under the control of the government than of the market, since the Central Bank directly determines the basic interest rate and the Treasury may reject offers from agents if the interest rates that they demand are too high.

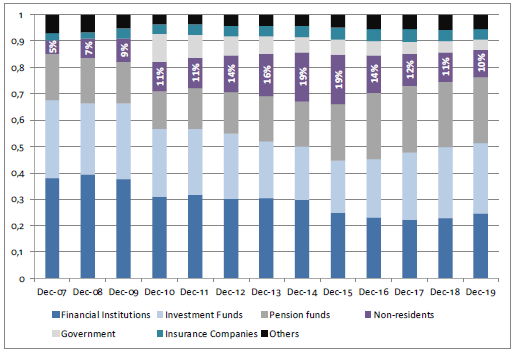

Another important feature is that the Brazilian public debt is mostly in the hands of domestic investors, notably financial institutions and institutional investors such as investment funds. In the past, financial liberalisation and the absence of capital controls allowed a large number of non-residents to enter the Brazilian markets, which could in fact increase the volatility of the foreign exchange rate and create certain vulnerability in the public bond market, should the Treasury be overly dependent upon these investors. However, as shown in Figure 5, the share of for eign investors that hold Brazilian public debt is relatively small and has been falling over the last few years -particularly after the country lost its international investment grade rating. The Treasury's capacity to place domestic public debt, therefore, does not depend directly on foreign 'bond vigilantes.'

The data analysed in this section suggest that the Brazilian government has a certain degree of autonomy in determining its economic policy. The evolution of this autonomy was very favourable during the period analysed. Although there is a structural question linked to external restriction, the Brazilian government has managed to evolve considerably over the last two decades in the sense of reducing its exposure in terms of debt in foreign currency. This occurred by means of a reduction in the foreign debt (both gross and net) and the process of deindexing the public debt with regard to the foreign exchange rate. In addition, the Brazilian State has a very reasonable capacity to borrow in BRL, without facing major restrictions, with a high success rate in primary auctions. The increase in Brazilian public debt in recent years does not seem to be correlated with an increase in the cost of the debt, contrary to the idea that an increase in debt could generate some perception of insolvency.

Therefore, from an empirical point of view, Brazil seems to have the policy space needed to build a fiscal policy framework aimed at achieving full employment and reducing inequality. However, one must consider the institutional aspects that constrain fiscal policy in Brazil. Are these the real barriers to the adoption of policies aimed at growth and equity?

FISCAL POLICY FRAMEWORK IN BRAZIL

The potential economic barriers erected by the external restriction and by eventual difficulties in rolling over and issuing domestic debt, as well as greater limitations in determining interest rates, are not empirically verified in the Brazilian case. Over the past few years, the Brazilian authorities seem to have enjoyed relative autonomy in defining economic policy, but were at all times constrained by the defined institutional framework regarding monetary policy, fiscal policy and the relationship between the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) and the National Treasury.

The starting point is the institutional mediations that influence the Brazilian government's spending, borrowing, and tax collection operations. The BCB acts as the financial agent of the Treasury, which manages its transactions through the Treasury's Single Account, which concentrates all operations and receives all the financial transactions of the government. The BCB is the only authority with the prerogative to issue currency in the country -the Treasury does not have this power-, and it is forbidden to grant, directly or indirectly, loans to the Treasury.

For MMT authors, in practice, taxes and public debt do not finance government spending (Rezende, 2009). The BCB uses open market operations to prevent monetary pressures arising from public spending on the interest rate to deviate from its target and compromise the operational functioning of the inflation targeting regime. In this sense, the sale of government bonds has an umbilical relationship with monetary policy:

In fact, it is a 'monetary policy' operation rather than a 'financing' operation. In the absence of daily open market operations, the overnight interest rate would fall to zero. By contrast, the conventional view suggests that when the government is running budget deficits, it is borrowing from the nongovernmental sector, thereby pushing up the overnight nominal interest rate. It should be clear that the Brazilian government is not financially constrained operationally -neither revenue constrained nor reserve constrained. (Rezende, 2009, p. 90)

From this perspective, it would make no sense to discuss sustainability and fiscal responsibility in the terms of the NCM. The Brazilian government, as the issuer of a sovereign currency (and not convertible into dollars), would be incapable of becoming insolvent in BRL7 and would always be able to issue obligations against itself denominated in BRL. There may be unintended macroeconomic consequences of the Treasury actions, such as an increase in inflation if productive capacity is put under pressure or a worsening of income distribution, but default is not a technical possibility.

In light of this interpretation, the limitations on fiscal policy would be mostly self-imposed, resulting from an alignment of Brazilian fiscal regulations with an economic conception centred on austerity (Rezende, 2009, pp. 94-95). In reality, with the strong adversities that marked the 'lost decade' of 1980, a process of imposing limits to the state's actions and subjugation of the fiscal policy to the dictates of sound finances began. As Lopreato (2013, p. 153) points out, the centrality of cutting the public deficit became a 'meta-synthesis of economic policy.'

In the Brazilian case, fiscal adjustment was seen as essential for successful price stabilisation, and was deliberately included in various stabilisation strategies and plans -and in particular in the Real Plan. The construction of this new institutional framework, guided by austerity, redesigned the pattern of state intervention in the economy. The need for permanent reforms that would change the fiscal regime in a lasting way was advocated in order to sustain low inflation. The agreement with the IMF in 1998 was responsible for increasing 'fiscal austerity in the face of the obligation to restore confidence in the solvency of public debt' (Lopreato, 2013, p. 184).

In the context of financial liberalisation and globalisation -and therefore increased speculative capital movements-, the Brazilian government became very concerned about the result of public budgets as a way to gain investors' 'confidence' and not influencing their expectations in a negative way. Moreover, the particularity of the post-stabilisation fiscal regime became budgetary rigidity. It became more difficult to meet all budget demands, considering the correlation of social and political forces, in a context of spending limits, obligation to generate primary surpluses, and low economic growth. The adoption of strict fiscal rules was the counterpart of such objectives outlined for fiscal policy.

Lledó et al. (2017, p. 8) define a fiscal rule as 'a long-lasting constraint on fiscal policy through numerical limits on budgetary aggregates.' These rules can have different objectives, such as sustaining public debt, stabilising the economy, or reducing the size of the state (IMF, 2009). In each jurisdiction, the rules have their own history. In Brazil, they were created at different times, reflecting the con-junctural needs of fiscal policy -or rather, of adjustment programmes. Our framework is composed of rules whose objectives are not necessarily interconnected, and which, in specific scenarios, may even conflict.

The 1988 Constitution already provided for the so-called Golden Rule, which prohibited the issuance of public debt that exceeded the amount of the government's capital expenditures. The rule implies that the government cannot go into debt in order to finance current expenses8. In practice, the rule has never been a limiting factor for the federal government's actions, with more recent rules having the role of constraining Brazilian fiscal policy more boldly.

The Fiscal Responsibility Law (LRF) introduced in 2000 a primary surplus rule, which was seen, at the time, as the main anchor of the government's fiscal policy, aiming at stabilising and reducing the debt/GDP ratio. The surplus target should be part of the draft Budget Guidelines Law, in the Annex of Fiscal Goals, responsible for establishing targets related to revenues, expenses, nominal and primary results, and the amount of public debt. This ex-ante fiscal constraint changed the entire federal budget process after its adoption.

This 'new' fiscal regime, however, was not able to promote a fiscal situation considered 'healthy and safe' due to the macroeconomic instability of the first years of the 21st century and the high interest rates. The surplus rule has an eminently pro-cyclical character: it allows for an increase in public spending at times of greater economic growth and, therefore, higher revenues, but forces the government to reduce spending at adverse times due to falling revenues (Vilella & Vaz, 2021).

Thus, the more active role of fiscal policy and the state depended significantly on the economic conjuncture. After years of faster economic growth, Brazil welcomed greater 'fiscal space,' with a reduction in public debt and the generation of surpluses. The 2008 international financial crisis brought greater tolerance to government intervention, but as soon as the worst moment of the crisis was over, with the deterioration of fiscal results, the clamour for a more austere policy was reestablished. In practice, the maintenance of the institutionality described above did not give fiscal policymakers the necessary leeway to adopt more progressive policies, in addition to weighing significantly in favour of tax incentives compared to increased spending.

In 2016, the Spending Ceiling instituted a brand-new fiscal regime, which established a draconian rule for government spending. The limit on the amount of primary spending each year is equal to the previous year's limit adjusted for inflation. It prohibited any real increase in the federal government's primary expenditures in a ten-year horizon9, regardless of the level of revenues collected by the government. In case of non-compliance with the ceiling, some triggers were provided, such as the prohibition of hiring personnel or creating mandatory expenditures (Brochado et al., 2019).

Although proposed as a rule to 'anchor agents' expectations,' the ceiling, in reality, implies a reduction in the size of the Brazilian state. As population growth is positive, the rule results in a real reduction in per capita primary spending over time (Gimene & Modenesi, 2021). Moreover, as the rule covers most primary expenditures and the level of mandatory expenditures is very high, there is a tendency to reduce discretionary spending, including investments associated with the provision of public goods and services to the population (Vilella & Vaz, 2021).

The Brazilian experience shows that the almost exclusive focus on fiscal adjustment, austerity and reducing the size of the state has ignored fiscal and financial mechanisms capable of providing the Brazilian state with the capacity to promote full employment, investments and reduce inequalities (Lopreato, 2013). All these restrictions, however, are self-imposed, since, as we saw above, the Brazilian government has monetary sovereignty and relative economic policy autonomy. The 'fiscal responsibility' associated with these rules, in reality, leaves in the background the need to guarantee the social rights established in the 1988 Constitution. Even if the Brazilian experience reveals that it is possible to operate within the current institutional limits, if there are conjunctural conditions that allow the authorities to do so, the structural framework still significantly restricts the possibilities of action of the Brazilian state.

FINAL REMARKS

The objective of this paper was to analyse the relevant macroeconomic and institutional characteristics of the Brazilian economy in the period from 1999 to 2019 that would permit to characterise the country's monetary sovereignty, its relative degree of economic policy autonomy, and the institutional impediments to the implementation of an alternative fiscal regime geared toward promoting economic growth and development, and meeting social rights and demands as prescribed by MMT.

In the empirical assessment, it was shown that the country was successful in reducing its exposure to foreign debt, both through the reduction of gross and net foreign debt, and through the deindexation of the public debt with respect to the foreign exchange rate. Although structural questions related to the external restriction still remain, this movement has conferred a larger policy space to Brazilian authorities. Furthermore, it was shown that the Brazilian government did not face any restrictions to borrowing in domestic currency, without difficulties in issuing debt or in controlling its costs.

The institutional aspects of Brazilian fiscal policy, however, impose constraints on government action, subordinating it to a vision concerned with the government's budget results and not with guaranteeing the rights and demands of society. This framework represents a major obstacle to a reorientation of Brazilian fiscal policy in favour of guaranteeing rights and reducing inequality, as well as full employment. It is possible to align Brazilian economic policy with an alternative fiscal regime, but to do so it is necessary to review the main objectives to be pursued and the framework of the country's fiscal rules.

Given the current economic scenario, instead of restricting the state's spending capacity, it is necessary to expand it in order to return to a path of economic growth oriented to long-term development, focusing on social deficits and the reduction of inequalities. A new fiscal framework is needed and MMT and functional finance could be seen as a viable alternative to accomplish such goals.