Introduction

Criminality is a crucial concern for post-conflict societies (Kurtenbach and Wulf 2012; Muggah 2005). In Central America, for instance, many people believe that official peace is worse than war and perceive criminal behavior to be more predatory than civil war violence (Fontes 2018; Moodie 2011). As crime grows more complex and transnational, the perception of unpredictable criminality worsens.

While the increase of predatory activities such as extortion, the diversification of illicit and semi-licit economies, and the growth of criminal groups challenge peacebuilding, there is little theorization about why organized criminality emerges in some post-conflict contexts but not others. There are also few attempts to unpack post-conflict criminal group behavior, even though recent research shows the limitations of assuming that criminal actors behave differently than armed actors with political agendas. Criminal actors may establish social orders as many rebels do. While this does not imply that criminals and insurgents are the same, the limits are blurrier than often assumed (Barnes 2017). Criminality after Colombia’s paramilitary demobilization illustrates this variation: while some groups engaged in extensive violence, others regulated it, and while some controlled the population tightly, others did not.

This article characterizes post-conflict criminal behavior drawing on the concept of criminal governance, that is, characterizing criminal groups’ ability to regulate behaviors outside and inside the organization (Lessing 2020). While some groups engage in criminal governance, others do not. I aim to explain this variation after the paramilitary demobilization. I argue that variation in criminal behavior can be path-dependent and is linked to the wartime power balance, specifically, the level of territorial control and political connections armed groups had before demobilization. The existing literature acknowledges that wartime orders shape incentives to remilitarize and organizational resources after conflict; nevertheless, I introduce a novel mechanism connecting wartime orders and criminal behavior-the learning processes among members of the demobilized group and those peripherally involved in the war. Where territorial control and political connections of paramilitaries before demobilization were high, criminal structures post conflict were likely to engage in governance. By contrast, disputed territories during wartime were less likely to generate criminal governance after conflict. While extant literature recognizes that wartime dynamics shape the post-conflict period, it focuses on former combatants’ behavior. This article contributes to understanding post-conflict, showing that analyses should consider behaviors and relations of armed actors beyond the group that demobilizes. It also contributes to a growing literature on criminal governance, demonstrating that long-term trajectories help explain criminal behavior. In other words, such behavior can be partially path-dependent due to complex learning processes that unfold over time. This does not mean that order always breeds order and vice versa. The analysis will show, instead, that at specific junctures armed structures reorganize in ways that facilitate the spread of learning processes and the connection across levels of criminal networks, which, in turn, can break or reinforce existing behaviors among and within groups. In Cali and Medellín, different processes unfolded when paramilitaries entered these cities. Paramilitary know-how and organizational resources were carried through key individuals (such as mid-level commanders), but also through gangs and other criminal groups.

After this introduction, section one explores the literature about post-conflict violence and crime, connects it to theories on criminal governance, and develops the argument based on the logic of path dependence. Section two summarizes the criminal evolution after the 2003 paramilitary demobilization. Section three substantiates the argument through case studies in Cali-an example of low criminal governance-and Medellín-an example of intense governance. The conclusions reflect on implications for understanding post-conflict and criminal governance.

1.Criminality after Conflict

This article’s central question is why does criminal governance vary in post-conflict scenarios?1 And specifically, what explains Cali and Medellín’s diverging trajectories?

Existing post-conflict literature does not address this question, but it identifies the lack of safety for demobilized combatants, limitations in demobilization, disarmament and reintegration, and socio-economic and cultural conditions as explanations of rearming and criminality (Godnick, Muggah, and Waszink 2002; Kurtenbach and Wulf 2012; Muggah 2005; Pearce 2016). Recent literature links remilitarization to recruitment strategies (Daly 2016) and ex-combatant crime engagement to individual social ties and the context of demobilization (Daly, Paler, and Samii 2020; Kaplan and Nussio 2018). A vibrant literature on the paramilitary demobilization shows that armed power at the onset of demobilization affects post demobilization outcomes (Howe, Sánchez, and Contreras 2010). These explanations provide crucial insights for this article, but they focus on remobilized or criminally engaged ex-combatants, overlooking criminality or violence that is not connected to ex-combatants. Some analyses recognize that crime increases after paramilitary demobilization cannot be solely linked to recidivism (Massé et al. 2011), but they do not analyze varied criminal group behaviors.

Recent studies of criminal violence help explain variations in criminal groups’ behavior. These studies find that state enforcement (Lessing 2017; Osorio 2015), the type of relations between criminal organizations, state structures, and political incentives, as well as competition between criminal groups, explain variations in violence (Durán-Martínez 2018; Trejo and Ley 2020). This article complements these studies by analyzing trajectories of criminal governance and long-term behavioral patterns rather than short-term homicide variations. While the difference in the outcome I analyze is subtle, it is significant. For example, variations in homicide between Cali and Medellín have been explained as resulting from criminal competition, state power configurations, and different security policies (Durán-Martínez 2018; Moncada 2016). This article complements these explanations by emphasizing how long-term learning processes that unfolded differently depending on the power balance at the juncture of paramilitary demobilization are crucial to understanding criminal behaviors afterward. Thus, I do not explain violence per se-although violence levels are an implication of the argument-but rather the propensity to regulate violence when necessary as a manifestation of an ability to govern inside and outside the organization. For example, a focus on criminal competition cannot fully explain why governance is greater and why homicides are lower in Medellín, even when multiple organizations operate and no monopolistic leadership exists. In other words, existing explanations cannot fully explain why the violent equilibria of criminal disputes are lower than in the 1990s, or why in Cali top-down orders to reduce violence are carried less effectively than in Medellín.

Lastly, recent literature advances arguments about why criminal governance emerges. Trejo and Ley (2020) argue that criminal wars force groups to diversify illicit portfolios, which leads them to develop governance ambitions to expand territorial control. As explained below, after the demobilization, illicit economies diversified, but some groups engaged in governance while others did not. Arias (2017) connects governance to relations between criminal groups, states, and civilians; my argument builds on this idea but analyzing how wartime legacies and long-term processes shape those connections. Finally, some arguments link criminal governance to retail drug sales; however, the findings remain contradictory: some studies argue that retail drug sales motivate the emergence of governance, as the need to control territory and buy local support increases (Blattman et al. 2021); other studies (Arias and Barnes 2017) link retail drug trade not to more governance, but to different types of governance. Since diverse economies and retail trafficking exist in Cali and Medellín, an explanation based on resources cannot account for different criminal behaviors.

This article expands the arguments above in three ways. First, it goes beyond the focus of post-conflict literature on former combatant remilitarization and behavior while analyzing overlooked non-state actors peripherally involved in civil war and varied post-conflict criminal behaviors. Second, it theorizes wartime and the post-conflict period as jointly determined by interactions between political and criminal armed groups and their relations with the state. Third, it emphasizes a novel mechanism of wartime legacies: learning processes. This last contribution helps to better understand criminal governance, even in non-conflict contexts.

a. A Path-Dependent Argument of Criminal Behavior

Existing literature considers multiple dimensions of non-state governance activities such as taxing (extortion), justice provision, or policy-making engagement (Arjona 2016; Arias 2017; Lessing 2020; Skarbek 2014). I operationalize post-conflict criminal governance focusing on the scope of social control, ability to regulate violence, and behavior of lower criminal ranks. These three dimensions represent key characteristics of non-state governance: regulation inside and outside the group and whether rules imposed by criminal groups affect civilian life (Lessing 2020). Criminal governance in a post-conflict scenario is higher when the scope of social control is high, groups can regulate violence if they wish to do so, and lower ranks behave more predictably. By contrast, low social control, less ability to regulate violence, and uncontrolled behavior by lower ranks characterize lower levels of criminal governance. Between these two poles, there is variation depending on whether populations see governance as legitimate and how many arenas of social and political life are controlled (Arias 2017; Lessing 2020). I focus on whether governance is intensive (or higher) or not, recognizing that the variation is wider. In general, higher governance means more predictable-but not necessarily more benign-behavior and a greater ability to regulate organizational and social affairs. I argue that wartime power configurations, in particular, the level of territorial control and political connections the demobilized group-in this case, the paramilitaries-had, shape criminal behavior after conflict by influencing incentives to fight or remilitarize, learning processes, and organizational resources through which criminal groups operate. Territorial control refers to whether power disputes existed during wartime among conflict actors and between those actors and criminal groups. Territorial control can change throughout a war; thus, my focus is on the existing balance of power at the time of demobilization, even though, as the case studies show, the specificities of the paramilitary expansion connect to longer historical patterns.

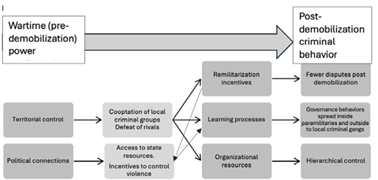

I analyze power configurations through the lens of paramilitary groups; however, the unit of analysis is a location because paramilitaries were embedded in networks involving other armed and political actors and varying across territories. In this sense, post-conflict criminal groups are studied beyond paramilitary remobilization, recognizing that demobilization also represented a critical juncture for other armed structures. Still, to understand how learning processes occur, it is essential to distinguish paramilitary from other armed, local criminal groups. Paramilitary groups are those whose agenda is attached to a political counterinsurgency objective; criminal groups are those motivated by profit from illegal and semi-legal economies. This distinction is fuzzy, particularly in Colombia, where armed groups combine political agendas, political behaviors, and criminal engagement. Paramilitaries were highly criminalized as they engaged in multiple illicit activities, particularly drug trafficking, and many combatants were motivated by profit (they received salaries) rather than ideology. Likewise, many criminal groups engage in political activities. Determining what defines a group as political or criminal supersedes this article’s goal, but for the theory’s purposes, the paramilitaries are groups with a stated political counterinsurgent goal. The connections between the two, summarized in Figure 1, explain how learning processes unfold.

The first mechanism explaining the connection between territorial control and criminal behavior refers to remilitarization incentives. When more groups operate during a conflict, credible commitments are difficult to enforce because the possibility of groups not participating in the process, not maintaining their promises, or not disarming is higher (Dixon 2009; Kreutz 2010). Nussio and Howe (2016) argue that violence quickly reemerges when demobilization disrupts power monopolies. Daly (2016) argues that when groups recruit locally, such power shifts are more limited as ex-combatants can foresee and adapt to those shifts. Following these arguments, we can expect that paramilitary-controlled territories were likely to experience fewer criminal groups after demobilization because spoilers or security dilemmas were less likely to emerge. While the power vacuum also generated incentives for rearming, the possibilities of old disputes reemerging were smaller. By contrast, in disputed territories, incentives for remilitarization were higher because some factions did not demobilize, and former combatants joined or created groups for protection or profit (Findley 2013; Rudloff and Findley 2016). Disputed territories were likely to see more groups and disputes after demobilization, as old disputes were recycled through existing and new structures. This paper expands on these explanations, showing that, to understand whether paramilitaries had control, it is crucial to consider their relation to other criminal groups, politicians, and state actors and whether they successfully coopted local criminal groups during their expansion.

The second mechanism that explains how territorial control affects post-conflict criminal behavior-and the article’s key contribution-is the learning processes of behavioral expectations and social norms among armed actors. Some studies analyze how perceptions and social norms during conflict affect law enforcement legitimacy (Deglow 2016) or induce changes in institutions and norms after conflict (Bateson 2017). Extending these ideas, I build on Pierson’s (2000) insight that path dependence emerges because social actors make commitments based on existing institutions. The longer an institution exists, the costlier it is to deviate from it. Positive feedback emerges through learning, coordination, and adaptive expectations. I argue that territorial control shapes coordination and adaptive behavior not only inside the demobilized group but also among criminal groups connected to it. Territorial control expands or reduces the repertoire of behaviors that criminal groups linked to the demobilized group can learn, thus creating path-dependent criminal behavior.

In the late 1990s, paramilitaries engaged in a ruthless expansion through the defeat or cooptation of other armed groups, penetration of the state and elections, and repression of civilians. When paramilitaries successfully eliminated rivals, coopted local criminal groups, and established territorial control, they were likely to engage in governance through brutal social control and gained skills to do so. During their expansion, paramilitaries attempted to eliminate rivals (guerrillas) and dominate criminal groups that could help them establish control and expand their rank and file. When paramilitaries successfully coopted local criminal groups prior to demobilization, local criminal actors learned from the techniques and strategies of paramilitaries as they expanded their authority over them. The possibilities of learning spreading down and outside the organization increased, and expectations that engaging in governance was beneficial were likely to spread outside the paramilitaries. Paramilitaries also capitalized on the knowledge and connections of local criminal actors. Thus, the learning flowed primarily from paramilitaries to criminal groups, as paramilitary commanders trained and forced local criminal groups they successfully coopted to follow their orders. Yet, learning also occurred from local criminal groups to paramilitaries, as their networks and territorial knowledge determined the success of the paramilitary takeover through alliances with local criminal leaders.

Territorial control also created know-how in controlling violence and regulating individual behaviors tightly in contradictory ways that legitimize violence and follow socially conservative values. Individuals who were not official combatants and thus did not demobilize, and those who remilitarized, capitalized on this knowledge. Former mid-level paramilitary commanders who were essential for remobilization (Daly 2014) and also criminal mid-ranks passed knowledge to new recruits. Thus, after demobilization, lower ranks who did not demobilize but experienced the benefits of regulating violence and controlling civilians, as well as those who remilitarized, replicated and expanded the behaviors existing during demobilization. By contrast, when paramilitaries disputed control by the time of demobilization, they were less likely to develop know-how in governance behaviors. As Arjona argues (2016), when a group is concerned about short-term fights, it has less time to establish social contracts with the population. In this scenario, after demobilization, both remobilized groups and those who never demobilized lacked control over the population and were unlikely to have experience in developing those relations after demobilization. In these circumstances, cycles of instability replaced self-enforcing “orderly” behaviors (Bernhard 2015).

The third mechanism explaining the connection between territorial control and post-conflict criminal governance consists of organizational resources. When paramilitaries gained control of an area, particularly alongside the cooptation of local criminal groups, they generated organizational mechanisms to monitor civilians and current or likely members of criminal groups (such as young men in urban areas). This monitoring increased coordination and spread learning down and outside the organization. By contrast, in disputed areas, if paramilitaries had difficulty controlling lower ranks during the war, criminal structures after the conflict were likely to be less hierarchical, showing fuzzier connections between higher and lower ranks.

Lastly, paramilitary expansion and the wartime balance of power also depended on relationships with state and political actors. Political networks provided paramilitaries with essential contacts to operate freely and know-how to navigate the state (Duncan 2015), thus making them resilient and powerful after conflict. Political connections refer to whether the interactions between the state and the demobilized group were mostly collaborative or confrontational. Because the state operates at multiple scales (national, regional, and local) and is not a unitary actor, these political connections vary in their degree of cohesion (Durán-Martínez 2018). When the paramilitaries established political connections with state actors at some levels, but these networks were fragmented, the level of collaboration was less predictable than when these political connections operated connecting levels and agencies of state power. Territorial control and political connections, although independent, interact. When paramilitaries established political networks that were stable and predictable but did not establish territorial control vis-à-vis other non-state groups, the political networks were likely to fragment over time. Thus, when paramilitaries had strong political connections, they experienced the benefits of state access, such as reduced enforcement attention or access to government resources. Territorial control strengthened these networks’ effect through the learning process it facilitated and created more incentives and opportunities to leverage state connections to control violence and life inside and outside criminal organizations.

2. Criminality after Paramilitary Demobilization

Paramilitary groups date back to a 1968 government decree authorizing the creation of self-defense groups to confront guerrillas. Such groups grew tied to the support of landowners and sectors of the state and the military (Romero 2003). In the late 1980s and 1990s, their connection to illegal economies, particularly drug trafficking, facilitated an unprecedented expansion. In 1997, decentralized structures came together under the umbrella organization United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC, for its acronym in Spanish). Between 1998 and 2002, paramilitaries consolidated and disputed guerrilla-controlled territories. According to the think tank CERAC, their expansion contributed to growing conflict casualties from 8,840 in 1998 to 16,720 in 2002.

In 2002, Álvaro Uribe was elected president on a popular platform, emphasizing the guerillas’ military defeat. Alliances between paramilitaries and politicians (known as the parapolítica scandal) were essential for the paramilitary expansion and played an important role in Uribe’s victory (Acemoglu, Robinson, and Santos 2013). Steady growth in state military presence and budget (Granada, Restrepo, and Vargas 2009) forced the FARC into a territorial retreat. Uribe advanced the paramilitary demobilization in a negotiation that was not public and lacked truth, reconciliation, and reparation provisions. However, pressure from victims and non-governmental organizations created mechanisms that ended up opening doors for weakening paramilitary structures (Barrera 2018).

Demobilization started in July 2003 with the signing of the “Ralito Agreement” and the concentration of combatants. By 2010, 35,710 paramilitaries had demobilized, a surprising number because the AUC declared to have 20,000 combatants.2 In 2007, organizations monitoring the demobilization warned about the rearming of paramilitaries. One of the first groups identified was Águilas Negras,3 but many groups emerged over time.

Labeling these groups has been controversial. The government initially called them Bacrim (an acronym for Criminal Gangs) to downplay their connections with paramilitaries, while human rights defenders labeled them neo-paramilitary groups to highlight the paramilitary influence (Verdad Abierta 2016). After 2016, the government classified these groups as either Organized Criminal Groups (GAO, for its acronym in Spanish) or Armed Criminal Groups (GAD, for its acronym in Spanish), recognizing the territorial control of some groups but still struggling to categorize their complex origins and behavior. Even though some structures were new, others had long traditions, such as Los Rastrojos and Oficina de Envigado. Their names changed constantly, and the government reclassified these groups to adapt law enforcement efforts.4 The groups’ fates also varied: many emerged and collapsed quickly, while others grew and expanded geographically (Barrera 2018).

Given these complexities, statistics on post-demobilization groups’ geography and size differ greatly among sources but show a pattern of group consolidation and growing territorial presence, as seen in Table 1. In 2008, the Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz) identified 23 groups with 2,500 estimated members in 260 municipalities. By 2014, the number decreased to 17 organizations in 336 municipalities that enrolled more combatants than in 2008, suggesting a centralization process. By 2016, 344 municipalities reported Bacrim presence. After that, the assessment was further complicated by the demobilization of the FARC, but as of 2022, Indepaz reported 13 major groups in 345 municipalities (Indepaz 2022). This article focuses on the period prior to the signing of a peace agreement with the FARC in 2016; however, as discussed below, the evidence suggests that criminal governance tendencies have not changed radically. Along the lines suggested in this article, the FARC demobilization had a more significant security impact in Cali than in Medellín.

Table 1. Bacrim presence in municipalities and number of criminal groups in Medellín and Cali, 2008-2022

| Number of municipalities with presence of neo-paramilitary/Bacrim | Number of groups with recorded activity in Cali | Number of groups with recorded activity in Medellín | |

| 2008 | 261 | 3 | 2 |

| 2009 | 275 | N.A. | N.A |

| 2010 | 353 | N.A | N.A |

| 2011 | 403 | 3 | 5 |

| 2012 | 409 | 3 | 4 |

| 2013 | 393 | N.A | N.A |

| 2014 | 385 | 5 | 2 |

| 2015 | N.A. | N.A. | N.A |

| 2016 | 351 | 4 | 4 |

| 2017 | 310 | 3 | 3 |

| 2018 | 274 | 3 | 3 |

| 2019 | 258 | N.A | N.A. |

| 2020 | 292 | 0 | 3 |

| 2021 | 332 | 3 | 3 |

| 2022 | 345 | 3 | 3 |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on data from Indepaz reports on presence of armed/narcoparamilitary groups. The numbers for Cali and Medellín do not include local gangs.

According to police data, by 2012, only 12 % of the arrested members of criminal gangs were former combatants. Yet paramilitary middle ranks were crucial for the emergence of new-armed organizations, and 53 % of arrested criminal commanders were former mid-level paramilitary commanders (Alarcón 2012; Valencia 2016). Thus, remilitarized commanders have been essential for criminal structures, but so have their connections to old criminal traditions.

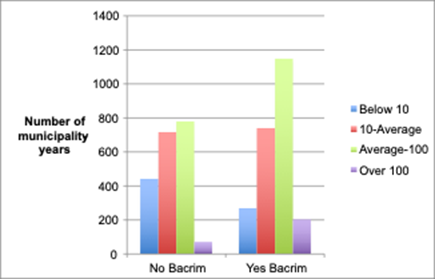

Post-demobilization criminal groups are predominantly urban, decentralized, and networked, and profit from multiple illegal and semi-legal activities, as occurs in Cali and Medellín. Some activities, like drug trafficking for export, have a long tradition, while others are old but have acquired more prominence, such as retail drug sales and extortion. Others are new, such as predatory loans known as “drop by drop” (gota a gota), where money is lent to locals with no collateral and disbursed quickly on the condition that they pay daily with high interest rates. Small-scale monopolies for food staples, such as milk, eggs, or alcohol, are also common. The groups’ electoral engagement is less clear than paramilitaries’ (Barrera 2018), but this does not mean they lack political implications or interests. There are also differences across groups; for instance, they are not all equally violent. As Figure 2. shows, between 2008 and 2013, among municipalities with criminal groups, 42 % displayed homicide rates below or equal to the national average, and 57 % had higher rates than the average. Lower homicides do not necessarily mean less violence (Durán-Martínez 2018) and can mask authoritarian social orders (Arjona 2016), but they signal different criminal behaviors.

Source: Author’s calculations based on data collected by Indepaz on the presence of criminal groups and homicide rates by DANE. N=4,392 municipality-years. Note: Each column represents the number of municipality-years within each range of homicide rates, by criminal gang presence. The average homicide rate for 2008-2013 is 29.10.

Figure 2. Criminal Presence and Homicide Rates

3. Post-Conflict Criminality in Cali and Medellín

To advance the argument, I carry out subnational comparative case studies (Snyder 2001) of Cali and Medellín based on fieldwork, twenty interviews conducted in 2016 specifically for this project, my long-time research with hundreds of interviews conducted in both locations, and subsequent visits in 2017, 2018, 2019, 2022, and 2023. The fact that my evidence spans other projects beyond the one that led to this article is relevant to the claims I make. The arguments were specifically explored in 2016, but the patterns I have identified in criminal behavior have been observed in subsequent visits for other projects. Interviewees include police and intelligence officials, social leaders, human rights defenders, NGOs, and former members of groups. Cali and Medellín represent a most similar case comparison (Przeworski and Teune 1970), sharing key characteristics but experiencing different levels of criminal governance after the paramilitary demobilization. Both cities were the birthplace of drug trafficking organizations and have experienced complex interactions between criminality and armed conflict; for example, guerrillas operated in both cities in the 1980s and established urban militias that interacted with growing drug trafficking organizations and local gangs, while paramilitaries entered and aimed to defeat guerrillas in the 1990s. They are Colombia’s second and third largest cities in terms of population and gross domestic product and provide ample opportunities for illegal economies. Yet Cali’s criminal structures after demobilization engaged in less governance, with limited ability to regulate and intervene in local affairs. Medellín exemplifies intense criminal governance, where groups regulate security and engage in local affairs beyond the illicit markets. These differences could be attributed to other factors that vary among these cities: Cali has experienced intense migration flows and racial segmentation and is dominated by an agro-industrial elite, whereas Medellín’s racial diversity and migration flows are not as sharp, and the economic elite is service oriented (Moncada 2016). These differences are crucial to explain variations in violence but are insufficient to explain why the demobilization marked a radical change in criminal behavior in Medellín but not in Cali.

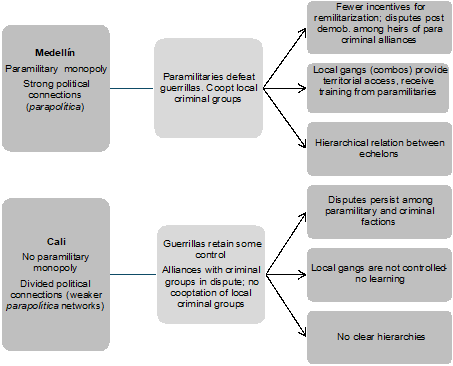

I first describe post-conflict criminal governance (the dependent variable) in each city, using information from interviews, field notes, secondary literature, government reports, and news reports. I then analyze how it connects to territorial control and political connections during the paramilitary expansion and demobilization. As summarized in Figure 3, in Medellín, paramilitaries successfully achieved territorial control, coopting and benefitting from the territorial rootedness of low-level gangs while imposing rules on them. This increasing coordination and shared expectations inside and outside paramilitary structures, which were maintained and expanded after demobilization through remobilized paramilitary commanders and non-demobilized criminal structures. In Cali, such cooptation did not occur, and paramilitaries did not achieve monopolistic territorial control; thus, governance behaviors pre-demobilization were less intense, and learning did not spread to local gangs. Although the outcome of interest is post-conflict criminality, in the strictest sense, this criminality mixes old and new groups, organized with some hierarchy among two or three levels. In Medellín, the top level consists of structures associated with the Oficina de Envigado (which traces its origins to the Medellín Cartel) and Los Urabeños or Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC) (which emerged after the paramilitary demobilization and contains remobilized paramilitaries). They are followed by mid-level (often family-based) criminal groups, which, given their longevity, control vast sectors of the city, such as Los Triana. The third level is the combos, local street gangs, which date back to the 1980s. In Cali, the organizations at the top have changed frequently, but also include groups tracing their origins to drug trafficking organizations (Los Rastrojos and Machos) and groups that emerged after the paramilitary demobilization, such as Los Urabeños (AGC), Los Buenaventureños, Águilas Negras, Shotas, and Espartanos. These groups contract out mid-level bandas and gangs, but as seen below, connections across this hierarchy are fuzzier than in Medellín. In both cities, there is fine-grained variation across neighborhoods, but there are clear patterns across each city.

a. Medellín’s Post-Demobilization Criminality

Medellín has a complex history of violence, with multiple armed actors operating since the 1980s. In the early 2000s, the paramilitary consolidation transformed security, and the demobilization represented a critical juncture, resulting in high levels of criminal governance after demobilization. Despite an uptick in violence around 2010, homicide levels are lower than in the 1990s, although organized crime is prevalent. The number of low-level criminal groups (combos) has regularly been estimated in the hundreds, for example, 200 soon after demobilization (Ramírez 2005), and a recent estimation counted 380 combos (Blattman et al. 2021), generally organized around one or two higher level structures. While combos are relatively autonomous, there is a hierarchy and coordinated expectations between high and low levels of criminality and significant social control.

Governance by criminal and political groups is not new; in the 1980s and 1990s, militias associated with demobilized guerilla camps engaged in social control through extortion and regulation of individual behaviors, intra-familiar disputes, and common crime (Ceballos 2001). Yet, the militias’ control was often unpredictable, given their hybrid and changing nature and lack of territorial dominance.5 Pablo Escobar also engaged in the provision of services to the community, but he did not strictly regulate the behavior of civilians or lower ranks working for him. Thus, the post-demobilization situation, although connected to long-time patterns, is different.

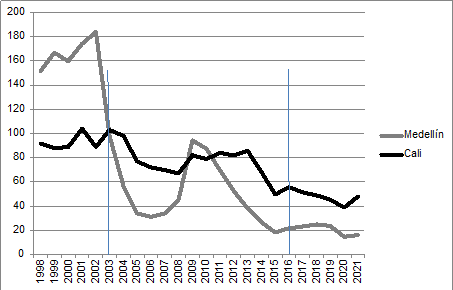

The first indicator of intense governance after demobilization is the criminal groups’ ability to regulate violence. As Figure 4 shows, after the demobilization in 2003, homicide rates declined sharply, then spiked between 2008 and 2012, and declined constantly after 2012, reaching low levels not seen since the 1970s. This does not mean that violence does not exist. Competition between or within criminal factions causes homicide spikes; when the criminal market tends to be monopolistic at the top, homicides decline, as expected in existing theories of criminal violence. Yet, homicides in the 2010s were lower than in the prior four decades, even when no single group controls the city. As a former secretary of security told me, “Medellín’s criminality has learned that even if a dead body on the street makes noise and scares the enemy, it also attracts the attention of authorities […] there is also group loyalty, which facilitates following the leaders’ decisions.”6 This statement illustrates how the lower threshold of violence reflects similar behavioral expectations, coordination, and consistent authority lines across structures. This learning process about the benefit of reducing homicides is also manifested in criminals’ willingness to pact with rival factions and in their offers to negotiate with the state. For example, in 2013, media sources reported a 30 % decrease in homicides associated with a truce between the Oficina de Envigado and Los Urabeños (El Colombiano 2013), and in 2016, the Oficina de Envigado submitted a proposal to negotiate with the government, which has resurfaced in several occasions (Semana 2016). Pacts between criminals translate into homicide reduction because of higher echelons’ coordination capacity and because low-level combos have learned that extreme violence is detrimental.

The second indicator of governance is the regulated behavior of lower ranks. Many combos are organized, connected to higher levels, and display long traditions and territorial rootedness. Regulated behavior means that low-level gang members are willing to reduce or hide violence and independently realize the benefits of controlling the community, thus facilitating the implementation of instructions from higher echelons. This regulated behavior makes combos essential for territorial control. For example, in April 2016, the post-demobilization group Los Urabeños aimed to enter many areas of the country to signal power and push the government to recognize them as a political armed group. In Medellín, it used local gangs to enforce an “armed strike” that froze life in many neighborhoods, and nobody could transit or open stores. Although Los Urabeños were powerful, they would not have been able to control neighborhoods without local gang support (Monsalve and Matta 2016).

A social worker described the regulated behavior of lower ranks (their willingness to reduce homicides and connect to the community) and the change it represented from pre-paramilitary demobilization in the following terms:

If you sit down with one of these boys [combo member], like the Chamo, it’s not like it was 20 years ago when they had a marijuana cigarette [bareto] in their hands with a completely different discourse; nowadays, they start talking with a book in their hands, read, follow the news, do social work, they take over juntas de acción comunal to see how to support social projects.7

The last indicator of governance is social control by criminal groups. Medellín’s armed groups are de facto authorities that regulate disputes and markets. In the words of a former secretary of security, “If a man beats his wife, and she denounces him with the criminal group, he will first receive a warning to stop, and if it happens again, he can be beaten or eventually expelled from the neighborhood.”8 Or, as summarized by a community leader, “[combos] resolve disputes among couples, an unruly son, any social situation.”9 Criminal groups engage in citizen participation processes (Abello-Colak and Guarneros-Meza 2014) and invest in licit businesses. This regulation of licit markets was first evident to me in 2017 when I saw two young men selling dairy products, systematically knocking on doors and keeping notes of every transaction. Someone later explained that products are sourced from vendors associated with combos or higher-level groups. The meticulous organization reflects a bureaucratization consistent with clear rules and routines.10

Criminal groups are efficient and interested in governing inside and outside the organization, largely because high- and low-level echelons have experienced long learning processes. Leaders can extend order all the way to the bottom even if the city is not controlled by one group. While criminal behaviors vary between neighborhoods (Blattman et al. 2021), criminal structures’ regulatory actions are more diverse and frequent than in Cali. This can be explained by the balance of power pre-demobilization, characterized by the paramilitaries’ success in monopolizing armed power and exploiting the combos’ territorial rootedness, which allowed communication between gangs and higher-level structures and strengthened the effect of strong political connections. This control, in turn, reduced the impact of older disputes over new criminal configurations and allowed learning processes that extended from the top to the lowest ranks.

b. Medellín’s Wartime Order

Paramilitaries entered Medellín in 1998, battling guerrillas and criminal groups. Disputes initially emerged among two paramilitary factions, the Bloque Metro and Cacique Nutibara, but by 2002, factions led by Diego Murillo, aka Don Berna, established control by defeating the FARC, coopting local gangs, and merging with existing criminal leaders. This monopoly was facilitated by close connections between paramilitaries, politicians, and state actors and by state military operations, like the Orion Operation in 2002, that eliminated the territorial hold of guerrillas (Comisión Nacional de Reparación y Reconciliación 2011).

The pre-demobilization monopoly resulted from the successful merging of paramilitary and traditional criminal structures. Don Berna, who began his career working for Pablo Escobar’s associates, started building connections with paramilitaries in the 1990s and, by 1997, became a paramilitary commander. His low profile prior to demobilization and his command over local criminal structures facilitated the merging between drug traffickers and paramilitaries. Don Berna’s monopoly is well known to have reduced violence. The key aspect that this article adds to the analysis of this monopoly is how it enabled paramilitaries to capitalize on the tradition and territorial rootedness of existing criminal structures through recruiting combo leaders and mid-level criminal commanders while training and infusing paramilitary techniques into criminal repertoires. As a social leader put it,

Our bandidos have been trained by guerrillas and then paramilitaries […] They started to engage in juntas de acción comunal and juntas administradoras locales after Berna. Berna showed them that they needed not only military control, but also social and economic control of the neighborhood.11

This was echoed by a former paramilitary commander: “We gained a social base during demobilization when we did the political training that taught them to be in the juntas de acción comunal, to have that social base.”12

The pre-demobilization paramilitary control reduced remilitarization incentives. Don Berna and his allies eliminated powerful opponents, and thus disputes for power post demobilization have involved heirs of the paramilitary expansion rather than radically different actors.13 This illustrates why the assessment of wartime power should consider criminal and state actors in tandem: although the paramilitary faction itself did not remilitarize (Daly 2016), older groups like the Oficina de Envigado and neighborhood gangs, while independent, were tied to paramilitaries, and their post-demobilization behavior was tied to wartime relations.

The pre-demobilization armed monopoly generated social control, organizational resources, and coordination that help explain the subsequent regulated behavior of lower ranks, given that it facilitated learning processes trickling down organizational structures and across armed groups. Paramilitaries disciplined combos, establishing clearer organizational hierarchies. This control paradoxically made the gangs essential to maintaining order. According to one interviewee,

the rootedness of the combos is too strong here. Love for the land is very strong; these kids can get themselves killed for loyalty to a narco. That’s what Don Berna realized; he would give them money for their mothers, for the party […].14

The combos hold power and knowledge, and even though extremely local, they have undergone their own learning processes. As the same interviewee explained, this is something Los Urabeños realized when they “arrived and wanted to enter the city by force; they found that Medellín is not easy to penetrate” and that it was easier to pay the combos to ensure control than to risk not accessing the city. Although connections between armed groups and street gangs as sources of information and territorial control have a long history, the contrast between the behavior of gangs before and after paramilitary demobilization illustrates how armed control affects the diffusion of learning processes at critical junctures. In the 1980s and 1990s, before the paramilitary takeover, no group controlled the city, and gangs were contracted to carry out violence and illegal activities; however, there was no interest from higher echelons in disciplining them. This changed when paramilitaries entered. It is relevant to note the longer trajectory here: paramilitaries perhaps would not have been interested in combos had they not been important players in the city’s order, but combos did not have enough agency to resist the paramilitary takeover and changed their behavior through their connection to paramilitaries.

Besides the successful territorial control, paramilitaries in Medellín created a network of connections among politicians. Don Berna himself declared that during the expansion of Bloque Metro, “many people who ran for mayor or senator had relationships with us” (El Espectador 2013). A combination of corruption and an interest in a successful demobilization by those politicians who were not coopted led to a tacit agreement between paramilitaries and state forces, where both shared an interest in lowering homicides, even though it was clear that some paramilitary commanders remained active after demobilization (Durán-Martínez 2018). As summarized by a former combo leader,

We saw that the paramilitaries entered into an alliance with legal authorities because while being together, the authorities started to see that it was advantageous for them too because in neighborhoods where police couldn’t show up, now they were able to enter; the paramilitaries helped them control robberies and domestic problems.15

Paramilitaries had strong political connections in Medellín and Antioquia, as reflected in the sentencing of at least 22 members of Congress and former Medellín Mayor and Governor Luis Alfredo Ramos for connections to paramilitaries. These networks, alongside territorial control, gave the paramilitaries and the criminal groups associated with them more experience in controlling and accessing state resources and higher incentives to minimize violence to facilitate those connections. As a former paramilitary commander explained, the political training of troops he conducted during the paramilitary expansion, and afterward as a member of a Bacrim, had the goal to “explain how to operate in legality. We explained how we elected and expelled mayors, all the political-electoral dynamics.”16 Although state capacity expanded in Medellín after the demobilization in terms of law enforcement and social service provision (Alcaldía de Medellín and Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo 2010), criminal groups have not stopped operating and rather have capitalized on their knowledge to benefit from state connections to avoid enforcement or access resources and policy-making opportunities.

In sum, the territorial control through the cooptation of local criminal structures prior to demobilization allowed paramilitaries to establish forms of governance that unleashed learning processes inside paramilitary structures and across the local organizations they coopted. Paramilitaries benefitted from the territorial knowledge and rootedness of local criminal groups. This learning process-and the governance behaviors-have persisted and criminals have learned that extreme violence attracts enforcement attention and hurts business and that a low profile is preferable. This learning process has trickled down to lower ranks, expanding the space for criminal networks to embed into communities and creating a relatively direct relationship between higher echelons and low-level gangs. As a social worker put it,

Each structure has mid-level authority, and so you say, I work with Caliche. Caliche belongs to the Medellín group, to Pichi’s command […] Here this guy belongs to this one; this is the aunt, this is the mother, higher up is the abuela. They use feminine names for security.17

This does not mean that a situation of intense criminal governance is preferable. As social leaders expressed to me, social degradation is high, illicit markets like sexual trafficking and prostitution proliferate, and young men and women grow up socialized in places where control by armed groups is tight. Challenging the combos’ rule is not an option even for respected community leaders. As summarized by a social leader,

We feel a tense calm in the city. It’s a peace that is not real […] if you looked under the blanket, you would see war, violation, vulnerability. There is fear and reticence to denounce because of the consequences that could bring. That has been devastating for human rights workers.18

The learning processes do not imply that criminal power dynamics have remained invariable. Notably, after Don Berna’s demobilization, he was extradited in 2008 when evidence of his continued criminal enterprise was impossible to hide, disputes re-emerged, and the fight for control among his heirs increased homicides (Arias 2017). This suggests that path-dependent criminal trajectories can be unsettled by state operations or by leadership changes and disputes, as expected from the literature on criminal violence. Yet the underlying structure and know-how of criminal operators can explain why, after the spike in 2008-2011, homicide rates continued declining and dipped below 1970s levels. This also relates to the fact that after this big confrontation, the battle between two different paramilitary lines receded.19

After the FARC demobilization in 2016, criminality has remained stable, with criminal groups engaging in intense governance. This can be explained through the argument I advance. Since the FARC was displaced from Medellín by 2002, by the time of its demobilization, there was no territorial structure that could remobilize independently, and there is no evidence that FARC dissident groups have territorial presence in Medellín; meanwhile, criminal structures attached to the long-term process unfolding since the paramilitary takeover remain strong.

c. Cali’s Limited Criminal Governance

Cali also has a complex history of violence that, in the 1980s, connected drug trafficking organizations such as the Cali Cartel (and their successors in the Norte del Valle Cartel in the 1990s) to militias, guerrillas, and paramilitaries and to gangs that were less territorial and less directly connected to criminal leaders than in Medellín. After the paramilitary demobilization, criminal groups operate, but the levels of criminal governance are low.

The first indicator of low criminal governance is the criminal groups’ limited ability to control violence. Since the mid-1990s, homicide rates have been higher than the national average; as seen in Figure 4, after the paramilitary demobilization, homicides declined slightly and further decreased after 2013, but as of 2022, the city remained one of the country’s (and the world’s) most violent cities. An indication of the criminals’ weak ability to regulate violence, even when they aim to, is that truces among larger criminal groups are documented-as in Medellín-but without translating into lower homicide rates (Bargent 2013). This occurs because higher echelons seem unable and, at times, unwilling to centrally control violence; in the neighborhoods, there are disputes for small pieces of territory (corners and streets), and leadership is often attached to how violent an individual is perceived to be (Observatorio Social 2010).

The second indicator of less governance is, thus, the lack of control of lower criminal ranks, which results from weak connections between higher and lower echelons and the inability of the first to control gangs despite using them constantly. According to a criminal investigator from the Attorney General’s Office,

There are [criminal] structures, but it’s difficult to get to the leaders with solid evidence; one must look for ways to take down those who become visible. [The leaders] put someone who carries all the criminal goodwill; one knows, for example, that someone is from Los Rastrojos, and one hears [nicknames] of the traditional bosses […], but it is very difficult to identify the bosses.20

Street gangs appear less sophisticated and connected to a single group or leader; they are also less essential for territorial control. A 2012 report identified 134 gangs, but only a few were characterized as highly sophisticated; most of them engaged in identity disputes, petty theft, murder-for-hire, and drug trafficking, with different levels of organization and connection with higher echelons (Personería Municipal de Santiago de Cali 2012). As two workers from a prominent NGO told me in 2016, “There are individuals who have been in illicit business for a long time, but no parche has dominated, and the names and organizations change frequently.”21This explains why the entrance of Los Urabeños to Cali was very violent, in contrast to Medellín. They fought with existing groups, yet it was possible for them to enter without using gangs, which were unreliable partners. As a result, criminal groups were also less able to regulate gang behavior. Paradoxically, this makes lower-level gangs less powerful, even if more violent.

Gang members often do not know who they work for, and instructions from higher echelons to reduce violence are not translated into homicide reductions. As a criminal investigator indicated,

Youngsters do not brag about their boss, their leader; here in Cali, they defend their territories […] This has been capitalized on by the capos, the bosses who tell them, “You in Floralia neighborhood, you have these two blocks, this park, you distribute drug trafficking, we can give you arms,” but that’s it. For them, it is not clear who they work for […] here one can’t say “the king of the comuna 20 is such and such.”22

A social worker elaborated on this, explaining that although bandas (petty crime groups less territorial than street gangs) connect to local and national criminal structures,

There is a dissociation between the bandas and the oficinas, between the old and young ones. And the young ones can be called upon, but they are not part of a functional structure […] is a relationship of conflict and cooperation, not a functional one.23

Criminal organizations also engage in limited social control. According to a community organizer, groups regulate illegal and legal activities, such as neighborhood milk sales (so that everyone buys from the same provider), drug distribution, or nightlife. But there are many groups, control is diffuse and limited to blocks within neighborhoods, and disputes are frequent.24 Although the portfolio of illicit and semi-licit activities has diversified, and both low and higher echelons aim to control markets, such control is dispersed and does not extend to the community or within the groups with clear rules. For example, although extortion has increased significantly over time, extortion that takes the form of what Colombian police label as classic extortion, where information about the victims is obtained and payment is demanded over the phone, is more prevalent than territorial extortion that is attached to “protection” payments in a territory (although the later has increased over time). As seen in Table 2, the numbers of direct extortion have been higher in Medellín than in Cali, in a pattern consistent with the different governance models in both cities. Likewise, I did not find reports of tightly regulated individual behaviors or low-level groups engaging in activities such as budget discussions or dispute resolution. Unlike in Medellín, where combos regulate personal conflicts, in Cali, “there is a problem of criminal coexistence; it is not always market disputes, but personal conflicts that escalate within those territorial disputes.”25

Table 2. Extortion in Cali and Medellín

| Year | Total Extortion | Direct Extortion | ||

| Cali | Medellín | Cali | Medellín | |

| 2010 | 54 | 153 | 5 | 38 |

| 2011 | 85 | 197 | 10 | 122 |

| 2012 | 86 | 209 | 12 | 121 |

| 2013 | 185 | 457 | 68 | 237 |

| 2014 | 210 | 281 | 88 | 155 |

| 2015 | 253 | 217 | 52 | 108 |

| 2016 | 148 | 302 | 39 | 133 |

| 2017 | 264 | 421 | 57 | 132 |

| 2018 | 275 | 208 | 84 | 482 |

| 2019 | 500 | 630 | 194 | 311 |

| 2020 | 531 | 506 | 83 | 141 |

| 2021 | 497 | 548 | 112 | 150 |

| 2022 | 317 | 572 | 132 | 218 |

| 2023 | 318 | 610 | 103 | 182 |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on statistics from SIEDCO, Policía Nacional. It is crucial to note that underreporting of extortion is high.

d. Cali’s Wartime Order

Cali’s low-intensity criminal governance connects to a disputed wartime order. Paramilitaries were unable to establish monopolistic control, and despite their political connections, no armed group fully capitalized on those connections. Paramilitaries did not entirely displace the FARC, and trafficking groups never merged with paramilitaries, though they collaborated closely. When criminals and paramilitaries consolidated alliances in the early 2000s, traffickers from the Norte del Valle Cartel were engaged in intense disputes between two leaders, Wilson Varela and Diego Montoya, who created their own armies to fight, Los Machos and Los Rastrojos. These leaders and their armies exploited alliances with paramilitary factions like the Bloque Calima to outpower rivals, but their disputes complicated an easy convergence between drug traffickers and paramilitaries. Both Varela and Montoya attempted to pose as paramilitaries and demobilize, but their trafficking past was too prominent and deemed risky by other paramilitary commanders (Semana 2005). As a result, no organization established a monopoly before demobilization, and to the contrary, the dispute between Varela and Montoya extended into the late 2000s. The lack of paramilitary control weakened governance behaviors before demobilization and thus did not generate learning processes around governance and organizational resources that could be maintained after demobilization. It also increased remobilization incentives and organizational disputes after the demobilization, when Los Machos and Los Rastrojos expanded nationwide, becoming some of the first recognized Bacrim. When Los Urabeños tried to expand to Cali and Valle, they allied with Los Machos to defeat Los Rastrojos, leading to a bloody war in 2013 (Verdad Abierta 2016). The lack of pre-demobilization monopoly thus generated many paths towards conflict after demobilization. This lack of monopoly also meant that paramilitary combatants and local criminal groups did not experience learning processes around governance, social control, and regulation of violence.

The lack of pre-demobilization monopoly also reduced organizational resources to control violence and spread social control tactics down the organizational hierarchy. Unlike Medellín, paramilitaries did not tightly coopt local gangs, which partially reflected a longer historical pattern: gangs have historically conducted jobs for drug traffickers, even after demobilization, but they are not gatekeepers for territorial control (Durán-Martínez 2018). This also explains why gangs did not undergo learning processes about the benefits of close relationships with the state during periods when those political connections ran deep when the Cali Cartel dominated the city in the 1980s: they were not systematically connected to an organizational hierarchy. Afterwards, there is no clear evidence of paramilitaries’ attempts to regulate and coopt gangs. As a result, local gangs are less sophisticated in their organization, behavior, and territorial rootedness. This lack of rootedness reflects Cali’s different social makeup and the systematic marginalization of communities along racial and social lines, which has left large sectors of the population isolated and excluded from the city, and young people in these marginalized sectors are simultaneously ignored, stigmatized, and over-policed.26 This makes them less attached to the territory but also more vulnerable to violence, as occurred during the paramilitary expansion and afterwards.

Connections between paramilitaries, drug traffickers, politicians, and state officials were strong, as exemplified in the network created by Senator Juan Carlos Martínez, connecting drug traffickers and paramilitaries (Revista Cambio 2011); however, the influence of paramilitaries in local administration was not as clear as in Antioquia and Medellín (Guzmán and Moreno 2007). Thus, these political connections were ineffective in deterring violence after the demobilization, also due to armed competition. Neither the state nor the criminals can generate effective mechanisms that reduce homicides. Persistent corruption that permeates the political class since before the paramilitary demobilization and goes back to the control of the Cali Cartel hinders policing, but protection networks are fragmented, so they also prevent armed actors from establishing a non-violent equilibrium. This instability also helps explain the trajectories after signing the peace agreement with the FARC. The FARC retained influence over time in Cali, and its dissident groups have a territorial presence alongside the ELN insurgency and new and older criminal groups (Indepaz 2022). Besides complex social conditions that are beyond this article’s scope to explain, this lack of control generates more violence in the post-FARC accord period than in Medellín, while low-level criminal governance persists. This creates risks for those who demobilized and supported the peace agreement with the FARC and more conflict among criminal groups and those who remobilized. Cali is among the top ten municipalities where social leaders (10) and signers of the peace agreement have been murdered and where massacres (7) have occurred since 2016 (Indepaz 2023).

In sum, the wartime power configuration created by relationships between paramilitaries, the state, guerrillas, and gangs influences Cali and Medellín’s post-conflict criminality by shaping disputes, intra-organizational relations, and learning of low-level gangs.

Conclusion

Criminal violence threatens post-conflict societies. By connecting literature on conflict recurrence and criminal violence, this article contributes to a better understanding of post-conflict and criminal dynamics. It shows the need to unpack the complex outcomes emerging after armed groups demobilize. It also highlights the importance of moving beyond assumptions that expect armed group behavior to be dictated by whether they are profit or rather politically motivated or of simplistic assessments of urban criminality that see gang connections to larger groups as simple outsourcing. A close look into post-conflict criminal organizations reveals variations in their operations that are often glossed over. These differences do not mean that some groups are more benign because orderly behaviors imply authoritarian social control, widespread illicit activities, and highly conservative social norms, as occurs in Medellín. Yet, they show that post-conflict outcomes should be analyzed beyond the rearming of combatants, considering crime dynamics that can be connected to wartime orders.

This discussion is central in Colombia’s current environment with a new set of challenges associated with the problems in implementing the 2016 peace agreement and the continuous operations of armed groups combining criminal motivations and political traditions. As the government of Gustavo Petro (2022-2026) has committed to seeking peace with all armed groups, including criminal ones, a clear understanding of how these groups operate and connect with other groups and conflict legacies is essential.

More broadly, this article argues that ideas of path dependence and learning processes are overlooked mechanisms in post-conflict analysis and can expand the growing literature on criminal behavior and governance. This does not mean that violence trajectories are always self-reinforcing or linear. Critical junctures, leadership and generational changes, and external pressures created by state operations, international pressure, and transnational dynamics can unsettle criminality and violence dynamics. Yet, a better understanding of how states, armed groups, and civilians evolve in complex security environments and shape each other’s expectations is relevant, especially considering that criminal violence can cause as many deaths as armed conflicts; thus, a thorough comprehension of it is crucial to find better responses to it.