Introduction

Recent advances in remote sensing (RS) for data collection processes during rescues, monitoring, and the search for solutions to reduce the impact of natural disasters on human societies have sparked the intrest of the research community. RS is the science of data collection from a distance while using sensors (Fig. 1). Remote sensors offer a comprehensive outlook and a plethora of information concerning various systems. They facilitate data-driven decision-making grounded in the current and anticipated conditions of specific variables. Typically, the technologies employed in RS are limited to detecting and measuring electromagnetic energy, spanning both visible and non-visible radiation, which interacts with surface materials and the atmosphere. According to these characteristics, RS is seen as an essential tool for risk assessment, surveillance, reconnaissance, and rescue operations 1.

Figure 1 Multi-modal sensor data platform based on UAVs for monitoring, reconnaissance, and surveillance tasks such as multi-spectral image analysis. The picture shows the different sensor modules, i.e., 3D LiDAR imaging and photogrammetry for mapping and recognition, acoustic localization, and electromagnetic spectrum analysis in real-time applications 1

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) are a category of aircraft that is suited for remote operation and control by a designated pilot, commonly referred to as the UAV control operator. While UAVs have been predominantly deployed in military contexts, there has been a notable surge in their deployment for civil applications, as is the case of agriculture. UAVs equipped with RS platforms have emerged as powerful tools for reconnaissance and surveillance applications (Fig. 1). These advanced systems provide real-time situational awareness, target identification, and data collection capabilities in various operating scenarios. Fig. 2 shows typical strategies to gather, process, and analyze temporal and spatial (terrain monitoring) data, as well as to combine it with other information (e.g., remote sensors) to support management decisions. With the increasing demand for extended mission endurance and optimized operational efficiency, energy-efficient methods have become crucial for UAV remote sensors in reconnaissance and surveillance missions. This introduction provides an overview of energy efficiency in UAV RS platforms for reconnaissance and surveillance, highlighting the significance of energy optimization and its impact on mission effectiveness 1.

Figure 2 Block diagram depicting the integration of UAV surveillance and recognition systems in scenarios involving rural and urban security. A UAV-based multi sensor platform generates multi-modal data used at the different stages in the workflow of a civil or military system for alert, surveillance, and search and rescue operations 7

Fig. 3 shows different sensor categories that can be installed in different positions of UAVs, so that the vehicle has the capability to effectively sense and comprehend its environment from all perspectives. Low-costUAVs are now indispensable for on-site fast data collection using Multi-Sensor Reconnaissance Surveillance System (MRSS) technologies to aid disaster management, such as mapping, monitoring, and the autonomous deployment of flying robots 2. In addition, UAVs employ smart interfaces to accomplish various objectives, including detecting radiation on the terrain and monitoring a wide range of attributes from physical features to thermal emissions in a given region. For instance, the use of UAVs for RS has proven to be the most effective approach for monitoring terrain via imagery. In contrast to RS utilizing satellite imagery or that performed from manned aircraft, UAVs provide the opportunity to obtain images with exceptional spatial and temporal resolution because of their capacity to maneuver and fly at low altitudes. One such application is accurate and evidence-based forecasting of farm produce using spatial data collected via UAVs 3. With the gathered information, farmers can find fast and efficient solutions to any issues detected, make better management decisions, improve farm productivity, and ultimately generate higher profits 3. Collecting real-time data helps farmers to immediately evaluate and react to environmental events. The final results include reduced operating costs, improved crop quality, and increased yield rates 4. Therefore, the selection of sensors is one of the fundamental building blocks of real-time RS 5. In conclusion, UAV RS is becoming an important means for reconnaissance and surveillance thanks to the flexibility, efficiency, and low cost of UAVs, while still yielding systematic data with high spatial and temporal resolutions 6.

Figure 3 UAV-MRSS sensor options according to the data generated by the different types of sensors and their manufacturing technology

Surveillance, reconnaissance, and targeting are critical factors for providing users with real-time situational awareness. The ability to instantly process and disseminate data collected from the field is vital in achieving terrain dominance. The MRSS is a sophisticated and smart multi-sensor surveillance and reconnaissance system that requires considering the multifariousness of devices (sensors) as well as the user’s requirements. In particular, a UAV-MRSS system integrates several sensors that capture different types of information with specific integration and processing needs 8. Fig. 3 shows different sensor categories that can be installed at different positions in UAV-MRSS platforms, so that the UAV can perceive its surroundings well from every angle.

9 categorized the MRSS technologies of satellites, UAVs, or manned aircraft based on their detection of non-contact energy reflection from the Earth. However, the feasibility of using satellite MRSS technologies has some shortcomings. First, satellites have a specific time cycle for acquiring information, including image capture. Second, the cost of satellite technology is considerably high 10. Third, the image resolution is low, making it difficult to obtain detailed features. Fourth, the temporal and spatial resolution of satellites is restricted, and environmental conditions such as cloud cover can impede a reliable operation 4. Fifth, the use of manned aircraft is often not feasible due to high costs, and it is not always possible to conduct multiple flights to acquire multiple crop images. The primary drawback of satellite technology is its high cost, making it inaccessible to many small and medium-scale commercial and subsistence farmers. This has led to the emergence of alternative delivery platforms (e.g., UAVs) 11) (12. UAVs are capable of rapidly covering vast and remote areas, reducing labor costs and requiring minimal operator space.

UAV-MRSS systems are noteworthy for their integration of several sensors, each with distinct information capture requirements and processing specifications 8. The three primary means of merging multiple sensors on platforms are as follows: redundant sensors, in which all sensors provide the same information; complementary sensors, i.e., the sensors provide independent (disjoint) types of information; and coordinated sensors, where the sensors sequentially gather information 13.

13 implemented three fundamental MRSS management strategies for synchronization. These strategies are part of a centralized scheme (Fig. 4) where all sensors provide measurements to a central node. Additionally, the distributed scheme, illustrated in Fig. 5 is employed, wherein nodes Exchange information at a specified communication rate, e.g., every five scans (a one-fifth communication rate). The centralized scheme may be regarded as a particular instance of the distributed scheme, where the sensors communicate with each other in every scan.Finally, the decentralized scheme (Fig. 6) is employed where there is no synchronization between the sensor nodes 13.

Given their considerable potential and the progress made in the field, UAVs will inevitably overcome some of the limitations of traditional MRSS. Specifically, UAVs possess proper Global Positioning Systems (GPS) in their software, which allows them to be programmed and guided with precision to specific locations. In comparison with manned aircraft, they are suitable for both regular and emergency scenarios. Furthermore, UAVs support a wide range of altitudes, are highly flexible, and have no strong demand for take-off and landing sites. Their high work efficiency is derived from being less affected by the external environment and capable of making secondary measurements at any given time. UAVs can be adapted easily to different types of reconnaissance and surveillance tasks, as well as to different growth stages. With their onboard autopilot system, UAVs can be controlled automatically and require less human intervention during data collection. The advantages of these platforms for MRSS applications include their high spatial resolution and the possibility of highly flexible and timely control due to reduced planning time. Consequently, most developed countries have adopted the latest precision agriculture technologies using UAVs to enhance their productivity 14.

New technologies and advancements in UAVs pose new challenges. For instance, smaller and medium-sized UAV platforms are only capable of carrying a limited number of multi-sensors, and the sensor-UAV configuration is exclusive, which means that data can only be collected from a single type of sensor. Furthermore, UAVs have payload limitations when compared to ground vehicles, which can result in equipment weight constraints. Additionally, environmental factors can impact the quality of the data collected by UAVs due to the lack of environmental controls. Aerial data collected by UAVs generally have a spatial resolution lower than those collected by ground systems. Moreover, precise geopositioning systems, which are required for military applications, precision agriculture, and land survey applications in civil engineering, mining, or disaster prevention and management, are not typically integrated into most platforms of this size. Moreover, there is scant literature on fully autonomous, cost-effective, multi-sensor UAV systems with standardized information extraction procedures for use in reduced-input precision agriculture applications.

Based on the above, the objective of this research is to develop a preliminary approach for the efficient use of energy consumption in UAV-based multi-sensor platforms for reconnaissance and surveillance (MRSS), which allows configuring multi-sensor modules for simultaneous or individual operation. In this vein, the aim of this paper is to propose a new UAV-based MRSS platform equipped with a set of modules (e.g., SIGINT, MASINT, GEOINT, navigation module) in order to monitor the environment and collect data in real time, making efficient of battery power.

The focal point of is research was the amalgamation of sensor modules through parallel computing. This integration allowed acquiring data, specifically georeferenced data including point measurements, reflectance spectra, and optical images. This facilitated the post-processing of subsequent data and the analysis of features.

To develop the preliminary approach, the following considerations were made. (i) The objective of this study is to develop a UAV-based multi-sensor platform for surveillance and reconnaissance applications, which entails the creation of both mechanical components and software programming for simultaneous multi-sensor data collection. (ii) The lifetime of the battery is assessed by using several sensor modules. This proposed system can cover vast areas and high altitudes while maintaining an energy-efficient approach, unlike the aircraft-based alternatives.

The research question is the following: What are the technologies adopted by multi-sensor UAV platforms for efficient energy consumption in surveillance and reconnaissance tasks? To answer this question, a multi-sensor UAV architecture based on MRSS technologies is proposed, and the energy consumption and battery voltage required for efficient use are established.

This document is organized as follows. In Section 2, the state of the art pertaining to UAV-based multi-sensor technologies is presented. Section 3 provides a comprehensive description of the proposed multi-sensor platform, along with a meticulous analysis of its major components. The results are presented in Section 4, offering a detailed insight into the energy consumption and battery life of a multi-sensor UAV platform. Section 5 is primarily focused on interpreting the data gathered while evaluating the approach. Finally, Section 6 provides some concluding remarks and highlights the paper’s valuable contributions.

Related Works

This section classifies some publications on surveillance and reconnaissance technologies that are relevant to the topic and analyzes several typical problems, including UAV multi-sensor platforms and embedded technologies for different applications,the limitations of using a single sensor to estimate certain characteristic features compared to the combining information from multiple sensor types that have the potential to reflect more complex information and provides a better opportunity for accurate yield estimation 15. Many interesting works have been carried out in this regard. For example, 16 described the implementation of a multisensor UAV system capable of flying with three sensors and different monitoring options. The feasibility of implementing a UAV platform utilizing RGB, multispectral, and thermal sensors was evaluated for particular objectives in precision viticulture. This platform proved to be a valuable asset for swift multifaceted monitoring in a vineyard 16.

17 presented an integrated monitoring approach able to provide a spatially detailed assessment of thermal stress in vineyards, combining high-resolution UAV RS and WSN proximal sensing.

The authors of 18 developed an autonomous multi-sensor UAV imaging system designed to provide spectral information related to water management for a pomegranate orchard. The system is composed of a primary UAV platform, a multispectral camera, a thermal camera, an external GPS receiver, a stabilization gimbal mechanism, and a Raspberry Pi microprocessor. All of these components are seamlessly integrated into a unified platform.

19 presented a combination of CCD cameras and a small (and low-cost) laser scanner with inexpensive IMU and GPS for a UAV-borne 3D mapping system. Direct georeferencing is accomplished via automatization using all of the available sensors, thereby eliminating the need for any ground control points.

20 presented a real-time, multi-sensor-based landing area recognition system for UAVs, which aims to enable these platforms to land safely on open and flat terrain and is suitable for comprehensive unmanned autonomous operations. This approach is built upon the combination of a camera and a 3D LiDAR.

15 evaluated the performance of a UAV-based RS system in cotton yield estimation. This system was equipped with an RGB, multispectral, and infrared thermal cameras to capture images of a cotton field at two distinct growth stages, namely flowering and the one prior to harvesting. The resulting sequential images were processed to produce orthomosaic images and a Digital Surface Model (DSM). Said images were then aligned with the georeferenced yield data obtained by a yield monitor installed on a harvester.

21 and 22 combined a UAV-based RGB camera, a multispectral camera, and a thermal camera to estimate the leaf chlorophyll content of soybean. The results indicated that multiple types of information could measure chlorophyll content with higher accuracy.

23 developed a ground-based platform that included an ultrasonic distance sensor, an infrared thermal radiometer, an normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) sensor, a portable spectrometer, and an RGB web camera to efficiently monitor multiple soybean and wheat plant traits.

24 proposed a semi-automatic sensing system for phenotyping wheat cultivars in field conditions. They employed a hyperspectral radiometer and two RGB cameras as the basis of the system, enabling the calculation of two distinct vegetation indices that are highly correlated to leaf chlorophyll content, as well as the fraction of green area per unit of ground area.

25 developed a field phenotyping system that incorporated three sensing modules to measure plant canopy height, temperature, and the NDVI. Three distinct data loggers were employed to capture sensor data. Said data were post-processed and subsequently combined into separate plots, which were then subjected to further analysis.

28 reported a high throughput phenotyping system for cotton. This system included sensors that automatically measured plant height, the ground cover fraction, the NDVI, and canopy temperature.

29 presented the open-source design of a multi-sensor UAV system with ROS that can be used for plant phenotyping and precision crop management. Data processing was introduced to extract plot-level phenotypic traits from calibrated images, and its performance was comparable to that of analogous studies.

UAV-based multi-sensor platforms are able to collect large amounts of high-dimensional data in short periods of time, which poses a challenge for modeling methods 30. In this regard, 31 evaluated UAV-based multi-sensor data fusion for wheat yield prediction at the grain filling stage and developed an ensemble learning framework to improve the yield prediction accuracy of machine learning (ML) models. This study employed ML techniques for amalgamating multi-sensor data acquired through UAVs, which were found to enhance the precision of crop yield predictions. The results convincingly demonstrated that multi-sensor data captured by low-altitude UAVs can be effectively exploited for early grain yield prediction via a data fusion approach and an ensemble learning framework with remarkable accuracy.

32 a multi-sensor payload for UAVs. This payload allowed generating multispectral point clouds with remarkable sub-centimeter precision. The authors integrated high-frequency navigation results from a Global Navigation Satellite System, photogrammetric bundle adjustment, and a specialized point cloud registration algorithm, improving the quality of the reconstructed point cloud by reducing the occurrence of ghosting effects and minimizing the amount of noise.

Most of the aforementioned works focus on particular UAV RS platforms capable of amassing substantial volumes of high-dimensional data and/or efficiently executing data processing in short timeframes, as opposed to addressing the energy consumption issues associated with sensor modules (payload). In the foreseeable future, more and more UAVs will take to the skies and deeply integrate real-time surveillance technology, affecting all aspects of our daily lives 33,34. UAVs allow taking high spatial resolution images due to their maneuverability at low altitudes.

Multi-sensor platform based on MRSS technologies

This section proposes a UAV-based multi-sensor platform for the integration of several sensor modules based on MRSS. This platform employs a new real-time modular architecture (i.e., a software and hardware architecture) for use in any type of UAV reconnaissance and surveillance applications. According to previous works, the design and functionality of UAV multi-sensor platforms have several characteristics, such as spectral, spatial, radiometric, and temporal resolutions. These characteristics are often a response to the limitations imposed by the laws of physics and the current state of technological development. Spatial and temporal resolution requirements vary significantly with regard to monitoring terrestrial, oceanic, and atmospheric features and processes. Each RS application has its own unique resolution requirements, resulting in trade-offs between spatial resolution and coverage, electromagnetic signal bandwidth, number of spectral bands, and signal-to-noise ratios. A multi-sensor platform is a sensor system that is precisely stabilized and can be used day and night to detect, observe, and identify objects, as well as for target tracking and rescue operations. It is specifically designed for day- and night-time operations and can function in adverse weather conditions. Thus, said platforms are compact and lightweight, making it easy to integrate into existing systems. When dealing with multiple module sensors, an efficient MRSS management strategy plays an important role in achieving a high overall performance (Fig. 7)

Figure 7 Interconnection between power and energy control, computing, data storage, navigation, and sensor modules and the flight control system for MRSS management, based on 35

An MRSS management strategy can be regarded as a general strategy that controls sensing actions, including sensor prioritization, sensor selection and sensor interaction. Sensor management has mainly one operation mode: sensor module assignment. This mode decides which sensor module combination will be assigned to which target over an area. The sensor module assignment problem involves determining the minimum additional energy consumption that would allow for a specific diagnostic. Fig. 8 illustrates an MRSS management strategy, which is executed via parallel computing control throughout three distinct stages. The process input involves four image-independent information sources in the form of RGB, multi-spectral, thermal, and LiDAR images. Given that the sensor modules generate data with varying features, independent processing is carried out. In the first pre-processing stage, the datasets are subjected to outlier detection and removal. Aftwerwards, the data are synchronized with respect to the system initialization moment, with the designated sampling period. In the final stage, the synchronized data undergo fusion. The detections recorded by the sensor modules are independently merged using an averaging operation and are subsequently fused with a complementary filter. The UAV’s onboard controller can then perform data processing in real time, which facilitates field decisions and coordination.

Figure 8 Flow diagram for the processing and georeferencing of different data types generated for the GEOINT module

The following subsections present a detailed description of the hardware and software used for our proposal. First, the hardware architecture is described, followed by the software architecture of the system.

Hardware architecture

Hardware architecture is a depiction of the physical arrangement of hardware components in a UAV, including the sensor modules and their interconnectivity (Fig. 9). The UAV’s hardware, which serves as a malleable mission controller, is tailored to deliver peak performance for vital missions.

Figure 9 UAV hardware for the proposed multi-sensor platform: a) top view of the assembly of the UAV, RF receivers, antennas, GPS, GNSS-INS, and autopilot modules; b) fully-assembled UAV including batteries, sensors, controller, and propeller; c) embedded control systems and onboard sensor types used for UAV applications; d) onboard multi-imaging sensors

The UAV platform used in this study (Fig. 9a) is a multi-rotor Tarot X8 II that boasts an impressive payload capacity of 8 kg and a flight time of 15 min. Its lightweight construction allows for a take-off weight of 10 kg with a 6S 22.000 mAh battery supply. The platform is equipped with eight power arms; it is an 8-axis multi-copter that features electric a retractable landing gear and a 5-degree umbrella-type folding arm. The autonomous flight of the UAV is governed by an autopilot (CubePilot), which operates on a dual CPU control system based on a GPS board, 3-axis accelerometers, yaw-rate gyros, and a 3-axis magnetometer, in order to follow a predetermined waypoint route. Flight parameters are communicated to the ground via a radio link operating at 2,4 GHz, whereas another channel at 5,8 GHz is employed for the transmission of RS data. In order to ensure optimal functionality and safeguard the UAV against electrical mishaps associated with the sensors, the aviation control and multi-sensor platform are powered by two separate power supplies. The sensors employed this work are depicted in Figs. 9a, 9b, 9c, and 9d, and correspond to: 1) UAV telemetry, 2) Vectornav VN200 antenna (GNSS-INS), 3) UAV GPS antenna, 4) UAV autopilot, 5) RF receiver autopilot, 6) GNSS-INS sensor (Vectornav VN200), 7) HackRF-One transceiver, 8) HackRF-One antenna, 9) DSLR Camera, 10) Parrot Sequioa multi-spectral camera, 11) LiDAR camera (ouster OS1-32U, OSO-32U), 12) XLRS outdoor microphone.

The aforementioned sensors have different and, to some extent, complementary selectivity regarding the morphological and spectral properties of the collected information, thus allowing multi-sensor data to determine complex features, increase the robustness of the system, and enable multi-feature determination. The payload weight is 1,8 kg, and the total weight of the UAV is 8,2 kg. The hardware sensor module (Fig. 9) is managed via parallel computing control (Fig. 9c). The control, which is responsible for reading the sensor module data and preparing it for transfer, is a fundamental unit for calculation within a sensor module. It serves to regulate task scheduling, energy consumption, communication protocols, coordination, data manipulation, and data transfer. The power consumption of the processor is predominantly determined by the duration of its support for sleep mode, and it is directly linked to the operation mode. The power consumption of these components is influenced by the operating voltage, the duty-cycle internal logic, and, most significantly, by an efficient manufacturing technology.

The Jetson-nano is used as a parallel computer controller that manages the onboard image sensors, Sony RGB, multispectral and 3D lidar, which transmit the images through the USB and Ethernet ports respectively.The weight of the hardware sensor module is 2,3 kg, and the dimensions are 180 × 180 × 110mm in length, width, and height. The hardware sensor module was developed as a purpose-built device.

The hardware sensor module requires two batteries to operate, which are shown as number 13 in Fig. 9. The hardware sensor module is powered by two 600W-hr lithium ion battery packs that also provide power to payloads through a dedicated enable circuit. Each battery pack has four 8,4 V Li-ion cells NP-F750-5600 mAh in series, which are also known as 3S and generate a nominal value of 22,2 V. The hardware sensor module is equipped with a current limiting circuit that serves to deactivate the power supply for the payload in the event of an unintentional current surge. The mean power for every payload connector must not surpass 50W. In the case of an over-current incident that disables the module’s power, the current limiting circuit can be reinstated via power cycling using the power button.

Software architecture

Software architecture involves making decisions about how software modules will interact with each other to meet the desired functionality and quality in the integrated system. As shown in Fig. 10, the proposed software architecture embodies a strategic approach. Its design was meticulously crafted to efficiently regulate and synchronize measurements from all sensor modules while simultaneously storing data sensors in the parallel computing control.

Figure 10 Interaction between software module components, including the multi-operations applications block, the navigation software module, the operation launcher, data storage, and the operating system. The multi-operations applications block manages multi-sensor hardware software modules, while the operation launcher executes autopilot requirements. The navigation software module handles geo-reference data and navigation, and data storage stores information in standard formats. These modules make up the MRSS management software architecture.

The software architecture satisfies a number of functional and non-functional requirements, including dynamic discovery, remote execution, and data retrieval and modification. Firstly, in the case of dynamic discovery, new sensor modules can be connected while the system is operational, and existing modules will be notified of their presence. Secondly, for remote execution, the customer sends function parameters and waits for the provider sensor module to return results. Lastly, for data retrieval and modification, the modules can report the internal state through variables, which can be synchronously queried or modified by other modules.

Additionally, the software architecture facilitates an intuitive protocol design and execution, allowing users to select the appropriate module for each mission, configure the necessary parameters, and execute the protocol with ease. Consequently, the functionality and purpose of each sensor module in the hardware sensor module have been meticulously defined during the module development process. The software, hardware, and operating systems have all been carefully analyzed to achieve optimal performance in embedded hardware, which will manage and integrate all inputs generated by the different modules that make up the system.

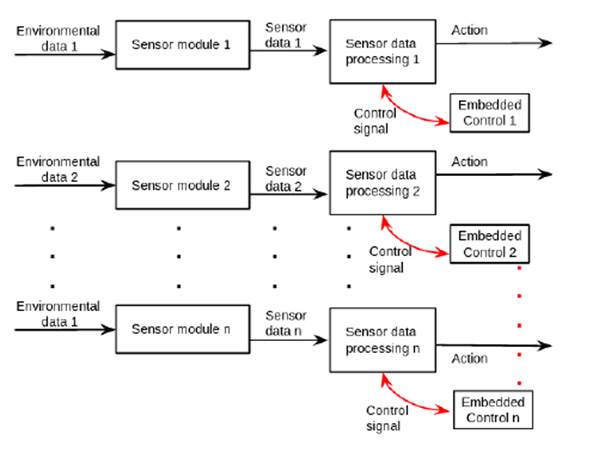

The software architecture management strategy used real time parallel computing control based on embedded edge computing. Fig. 11 shows the MRSS management system, which uses real time parallel computing for task assignment through a symmetric multi-processor (MPCore CPUs) from the embedded control system. MRSS parallel computing has two significant benefits: first, it controls the processes independently and increases the real-time data processing performance of each module: second, it makes efficient use of energy consumption, increasing its cost-effectiveness and reliability.

Figure 11 Interaction of software modules and their allocation to a particular core of the main processor for MRSS control utilizing real-time parallel computing

The software architecture employs an embedded Linux board as the main onboard control module to extract data from the sensor modules. The embedded onboard controller runs a custom Ubuntu 20.04 ARM, which is used to control the sensors and acquire data. Our software architecture was implemented using the C++ and OpenCL languages. Using C++ is highly appropriate in the modeling of multi-sensor engagements in UAVs. Conversely, OpenCL, an open and non-proprietary standard for the parallel programming of various accelerators utilized in heterogeneous computing, is well-suited for cross-platform applications and can be found in supercomputers and embedded platforms.

Fig. 12 corresponds to an interaction diagram showcasing the mutual engagement between sensor modules and parallel computing control during a UAV mission, as well as the way in which said modules function synchronously and their sequence. The interaction diagram serves as a means to illustrate the dynamic behavior of modules. The procedures that bring about real-time interaction take place when the request is made, and they are subsequently dismantled after the process has culminated. The transfer of sensor data from one module to the embedded control is illustrated by the labeled arrows.

Each individual occurrence of an event module is comprehensively paired with a distinct instance of a sensor module. These modules support a multitude of ideal sensor data sets, as well as a set of impairment parameters, ultimately producing a meticulously curated collection of sensor data. This particular collection of data is inclusive of sensor errors that are determined and classified based on the impairment parameters and the ideal input data. In current times, the processing of remote sensing that pertains to UAVs is primarily conducted in the ground system after the acquisition of images. As UAVs are equipped with an extensive array of sensors (payload), the data obtained by these sensors are inherently diverse, and the aims and objectives they serve are equally varied.

The software architecture includes four modules (GEOINT, SIGINT, MASINT, and navigation), which represent all sensors and the corresponding electronic devices for data collection. The following sections provide a detailed description of the above-mentioned modules.

Geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) module

GEOINT is an interdisciplinary field that incorporates the techniques of geography, cartography, and aerial photography, as well as computer science, mathematics, and computer-based modeling, to support national security, public safety, disaster prevention, and relief. GEOINT analysis uses data from multiple sources to create a comprehensive visual representation of an area of interest. Fig. 13 shows the GEOINT module components. The precise task of the GEOINT module is to effectively identify and concisely consolidate information within designated plot boundaries.

Figure 13 GEOINT block diagram composed of three major components. To produce multi-imaging data and their geo-localization, the processing unit employs the GEOINT module and navigation module components.

GEOINT analysts must be able to effectively communicate their findings to decision-makers and other users of GEOINT products. They must also be able to work effectively as part of a team and use a variety of GEOINT-related software applications.

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) module

The main objective of SIGINT is to monitor the radio spectrum to obtain basic information about a signal, such as its power and frequency, in order to identify possible threats in the area where a survey is conducted. Its general block diagram is shown in Fig. 14.

Figure 14 SIGINT block diagram, which consists of three main parts. The processing unit uses SIGINT and navigation module components to generate radio frecuency data and their geo-localization.

The SIGINT diagram is shown in Fig. 15. Here, the SIGINT module is controlled by a processing unit responsible for executing the following tasks: detecting, capturing, recording, and storing data in the form of radio frequency signals in the bands parameterized by means of SDR hardware. This is based on software requirements.

Figure 15 Fundamental constituent components of the SIGINT module, such as the VHF/UHF antenna, SDR 26, and the process unit.

A block design implementation of our proposed SIGINT methodology was presented in a preliminary work 27. The SDR design breaks with the paradigm of prefabricated communication devices, since it contains an RF block that can be reprogrammed and/or reconfigured using a System-on-Chip (SoC) or an embedded system such as an FPGA through a program or custom software solution.

Measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) module

Spectrum monitoring is an automated and intelligent infrastructure that operates in real-time, utilizing machine-machine technology to obtain and accumulate monitoring data. This data is then made readily available to regulators in an intuitive manner for the purpose of dynamic, intelligent, and efficient spectrum management. To this effect, this subsection proposes a MASINT module for acoustic monitoring via acoustic sensors. The proposed architecture of the MASINT module is presented in Fig. 16. It consists of a processing data unit, a navigation unit, a sensor module, and a data storage unit. The MASINT module includes acoustic sensors designed to capture sounds from different sources, which can be analyzed for different purposes. Acoustic sensors are commonly employed as cost-effective and straightforward devices to cater to band-specific monitoring prerequisites, complemented by their signal processing capabilities.

Figure 16 MASINT block diagram consisting of three main parts. The processing unit uses MASINT and navigation module components to generate acoustic data and their geo-localization.

Fig. 16 shows a diagram of the components used for the MASINT module. For acoustic data generation in recognition tasks, it has a single sensor per platform and it is used whenever the system is moving with geo-referencing. In the case of surveillance applications, several acoustic sensors arranged to estimate direction and distance can be selected. However, this is not part of the initial objective, and only a possible implementation will be studied in the future. The main features of this module include three measurement data for radio monitoring and signal analysis and processing.

Navigation module

The navigation module works at the same time or in synchrony with the data collection of each one of the different sensors in the SIGINT, GEOINT, and MASINT modules to correctly geo-reference the data sensed. The real-time clock (RTC) is used as a basis from an embedded system. Fig. 17 shows the navigation module diagram and its respective components. Among the UAV navigation techniques, the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) and the Inertial Navigation System (INS) modules are extensively employed given their global reach and ease of use in relative navigation. Nevertheless, GNSS observations are susceptible to various types of faults that stem from transmission degradation, ionospheric scintillations, multipath, spoofing, and numerous other factors. On the other hand, the Inertial Navigation System module is used to determine the data in space, angular velocities, and accelerations. It is constructed upon the basis of at least one 3-axis gyro and a 3-axis accelerometer.

Experiments and results

This section presents the research results regarding energy utilization and the lifetime of batteries in a multi-sensor UAV system. Under normal conditions, all devices on the platform are connected to a single battery, and each module is non-simultaneously activated. For experimental evaluations, each module is connected separately to the battery, and data are collected for 15 min. Experimental evaluations were conducted to understand the impact of energy consumption on performance and battery life, which is crucial for the efficient and sustainable design of these platforms. Energy consumption was analyzed in different operating modes of the sensor modules, both static and dynamic, and the energy components of each module were examined in detail. Additionally, battery lifetime was analyzed while considering factors such as capacity, state of charge, and degradation over time. The obtained results provide valuable insights for decision-making regarding sensor selection, energy management, and UAV mission planning.

Energy consumption model for MRSS platform

This subsection section provides an experimental assessment in order to showcase the plausibility of the suggested UAV-based RS platform. In the base case, all sensor modules have two modes of operation (static and dynamic), in which they consume a certain amount of power depending on the configuration used. For a connected device, the voltage and current vary depending on its operating state; if it is transmitting or receiving over a period of time, power consumption increases.

1. Static mode is the fixed amount of energy consumed consistently for a particular module (e.g., the MASINT module). Static mode, which is also defined as sleep mode is the energy consumed Esleep in the absence of any activity. Table I shows the energy consumption of different sensor modules. When a sensor module is operating in this particular state, the energy utilization of each module can be approximated, taking into account the time and power consumption. An illustration of this is the calculation of the energy consumption Esleep in inactive operation, as demonstrated in Eq. (1):

where PSleep and tSleep are the power consumption and time duration in static mode, respectively.

2. Dynamic mode is the energy required for states in which each device consumes an amount of energy Edevice during active operation, e.g., a camera capturing and processing a frame Eq. (2). To calculate the dynamic mode, the energy dissipated in any particular configuration over 15 minutes of operation is measured, obtaining an average energy measurement. The energy is determined in the same way as that in static mode, i.e., by multiplying the power consumption and the time duration, as shown in 2:

Table I shows the energy consumption data, estimated discharge voltage data, and deep of discharge data in dynamic and static modes obtained from each sensor modules, this modules were explained previously in Section 3.2. The energy consumption in dynamic mode for the each sensor module wascalculate using Eq. (3) by each of the devices (i.e., embedded controller, microphones, etc.).

where EWU is the energy consumed by the embedded controller; Evecnav is the energy consumed by the Vectornav; Epyle is the energy consumed by the Pyle amplifier microphone, and Eshure is the energy consumed by the Shure amplifier microphone typical devices used in the case of the MASINT module.

Table I shows the estimated discharge voltage for each sensor module in dynamic and static modes. Eq. (4), which relates the consumed energy E to the discharged voltage V of the battery, is given by

where E is the consumed energy, V is the discharged voltage of the battery, and Q is the battery capacity. The aforementioned equation posits that the energy consumed is equivalent to the multiplication of the voltage discharged and the capacity of the battery.

Finally, to estimate the battery lifetime of a MRSS platform, it is necessary to take a close look at the energy consumption of each device in the sensor modules. After establishing an average energy consumption as a baseline, designers can calculate the battery lifetime using the method proposed in Section 4.2. This paper does not deal with battery lifetime prediction methods.

Battery lifetime

The battery in dynamic mode constitutes a pivotal consideration in the selection of a secondary energy source. Rechargeable batteries have a limited lifespan and progressively deteriorate regarding their capacity to retain charges over time, which is an irreversible phenomenon. The reduction in battery capacity concomitantly diminishes the duration for which the product can be powered, commonly referred to as runtime. The battery’s lifetime is primarily influenced by the cycle life. The cycle life of a battery is defined as the total number of charge and discharge cycles that the battery can complete before experiencing a decline in performance. The depth of discharge (DoD) significantly affects the cycle life of Li-ion batteries. The DoD represents the amount of battery storage capacity utilized. Li-ion batteries are deep-cycle batteries, possessing DoDs of approximately 95 %. The typical estimated life of a Li-ion battery is roughly seven years or 2.000 to 2.500 full charge/discharge cycles before the capacity falls below 80 %, whichever occurs first. Conversely, the State of Charge (SOC) constitutes a significant parameter of li-ion batteries, indicating the level of charge within a battery cell. According to 37 and 38, the SOC indicates the instantaneous charge of a battery as a percentage of its máximum capacity 39, which is given by Eq. (5).

where the instantaneous maximum capacity is represented as Qmax, while the Coulomb counting method is employed to obtain the instantaneous stored charge Q(t), wherein Q0 is indicative of the initial battery charge.

Similarly, the depth of discharge (DoD) serves as an indicator of the proportion of the overall capacity that has been discharged Eq. (7).

According to the literature 37, the maximum capacity of a battery typically fades to 80% of its original value before it is considered to have reached the end of its life. Hence, it is imperative to engage in regular maintenance and appropriate handling of batteries in order to extend useful life. An accurate forecast of the long-term effectiveness and wellness of batteries requires modeling battery degradation. The service capabilities of Li-ion batteries as storage systems are impacted by the deterioration of their capacity. The prognosis of battery health is facilitated by the estimation of lifetime and capacity. An estimation of battery lifetime can be made by considering the transaction period and consumption of the selected configuration. To determine the battery lifetime LT, one must divide the battery capacity CBat by the average device current consumption IL over time Eq. (8).

Raw data collection in this regard is based on taking measurements and then cleaning and processing them to analyze the energy consumption behavior of each device, i.e., the embedded control with each sensor module. The average is the sum of the amount of current consumed when collecting data, scaled by the ratio of time that the sensor module is collecting data. Fig. 18 allows graphing and tabulating the collected power consumption data collected, as well as a real-time visualization of each sensor module.

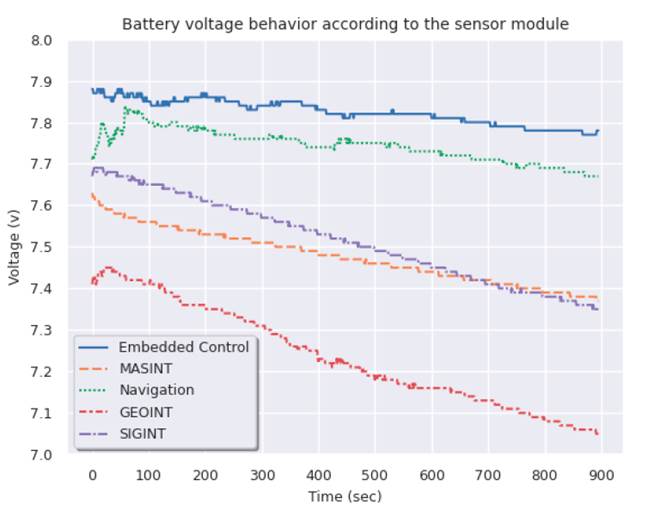

Figure 18 Dynamic-mode behavior of the battery voltage with respect to each sensor module: a) GEOINT, b) MASINT, c) navigation, d) SIGINT

The time presented in Figs. 18 and 19 is around 15 min (i.e., 900 seconds), during which the battery’s discharge voltage is produced from each one of the sensor modules. The battery’s discharge voltage is the amount of electrical potential (voltage) loss caused by the sensor module in dynamic mode. The cut-off Voltage (Vco) is the voltage at which the battery is specified to be fully discharged. In this sense, Vco is equal to 6,1 V. While there is usually charge remaining, operation at voltages lower than Vco can damage the battery.

Figure 19 Correspondence between the discharge voltage of the battery and each individual sensor module. Blue represents the embedded control, orange represents MASINT, green represents navigation, red represents GEOINT, and purple represents SIGINT.

Fig. 18 shows the discharge voltage caused by the sensor module, which determines the fraction of power withdrawn from the battery according to the sensor module used (e.g., SIGINT). For example, if the DoD of the NP-F750 battery is 20% (as given by the manufacturer), then only 20% of the battery capacity can be used by the sensor modules. In addition, according to the manufacturer, the lifetime of a NP-F750 battery is in the range of 2.000-2.500 cycles. A daily cycle of charge and discharge for approximately seven years is ensured. After this period, the battery retains 80% of its initial capacity, allowingit to operate for 2.000 cycles. It is only when the battery’s aging process has progressed to the point where voltage drops render the battery unusable that the capacity fades to 60 %.

For the embedded control, an expected discharge voltage of 8,07 V and a 1,5% DoD were taken as a theoretical reference for the static mode, in addition to an expected theoretical value of 7,89 V and a DoD of 11% for the dynamic mode I. Fig. 19 shows that a discharge voltage of 7,78 V is reached, with a Depth of discharge of 16% for the dynamic mode. According to these results, the life cycles for the continuous use of this module are approximately 2,625. This entails a battery lifetime of 7,35 years.

As for the GEOINT module, an expected discharge voltage of 7,91 volts and a 10% DoD were taken as reference for the static mode, as well as an expected theoretical value of 6,66 V and a DoD of 72% for the dynamic mode I. In Fig. 19, a DoD of 47% is observed, reaching a discharge voltage 7,16 V (Deep cycling), which entails a battery lifetime of 4,6 years.

Regarding the MASINT module, an expected discharge voltage of 8,05 V and a 2,5% DoD were taken as reference for the static mode. For the dynamic mode, an expected theoretical value of 7,70 V and a DoD of 20% were used. Fig. 19 shows that a discharge voltage of 7,5 V is reached, with a depth of discharge of 30% in dynamic mode. According to these results, the life cycles for continuous use of this module are approximately 1.937. This entails a battery lifetime of 5,4 years.

The theoretical reference for the navigation module included an expected discharge voltage of 8,07 V and a 1,5% DoD for the static mode and 7,84 V and 13% for the dynamic mode I. Fig. 19 shows that a discharge voltage of 7,67 V is reached, with a depth of discharge of 21,5% in dynamic mode, i.e., the life cycles for continuous use of this module are approximately 2.453, which entails a battery lifetime of 6,86 years.

Finally, for the SIGINT module, an expected discharge voltage of 8,04 V and a 3% DoD were taken as a theoretical reference for the static mode, as well as 7,51 V and 30% for the dynamic mode I. Fig. 19 shows that a discharge voltage of 7,34 V was reached, with a depth of discharge of 38% in Dynamic mode, entailing 1.937 life cycles and a battery lifetime of 5,425 years.

Discussion

This manuscript proposes an integrated multi-sensor platform with the objective of achieving high throughput data collection. The platform comprises eight sensing modules: a Vectornav vn200(GNSS-INS), a HackRF One, a DSLR Camera (Sony Alpha-A6000), two XLRS outdoor microphones, a LiDAR Camera (ouster OS1-32U, OSO-32U), and a Parrot Sequoia multi-spectral camera. The use of UAVs in lieu of terrestrial means of data collection has rapidly garnered widespread acceptance due to their significantly improved efficiency. Despite being more difficult to implement than conventional methods, the integration of an all-encompassing approach has the potential to ensure uniform and precise outcomes.

The development of a multi-sensor platform may be an important breakthrough for the maturity of emerging UAV applications, especially when architectures are created to support the development of such platforms. Nevertheless, the development of architectures should also be combined with energy consumption analyses regarding implementation, deployment, and performance, bringing these architectures to a more realistic setting. This analysis allows studying the real and theoretical behavior of a battery regarding the discharge voltage, DoD, and the energy consumed. This approach highlights the importance of battery characterization in order to have a real time reference that ensures successful multi-data collection missions with UAV platforms. It is anticipated that, with each charge and discharge cycle, the actual values will diminish considerably as a result of battery degradation.

The efficient scheduling and budgeting of battery power in multi-sensor applications has become a critical design issue. In this sense, our work studies how energy consumption, battery lifetime, and multi-sensor capabilities affect battery lifetime. The high energy consumption associated with modules such as GEOINT leads to deep discharge in excess of a 20% DoD, resulting in a maximum battery degradation of 2,4 years. These findings allow designers of multi-sensor platforms to determine the necessary battery capacities to enhance sensor energy consumption, thereby minimizing the total costs of UAV-based RS platforms.

Although considerable efforts have been devoted to the development of multi-sensor platforms for UAVs, there are several formidable challenges in this field. A crucial task is to accurately estimate the energy consumption requirements of each component. By selecting an appropriate multi-sensor approach during the design phase, the hardware underpinning the platform can be optimized for energy efficiency, thereby facilitating the effective power management of the system. However, certain multi-sensor modules lack comprehensive insights into the battery aging process. Consequently, it is desirable to devise a means of integrating the identification of aging mechanisms with online battery health assessment.

Battery lifetime may be influenced by deep cycling, as is the case of the GEOINT module. In contrast to other deep-cycle batteries, fractional charges extend the lifespan of a lithium battery.

Finally, the effect of parallel computing control on energy consumption is considered. It is observed that, when two processors are used, the management strategy dynamically increases the frequency of the processors, resulting in increased energy consumption. On the contrary, when using four processors, the management decreases the processors’ frequency of operation, resulting in reduced energy consumption.

Conclusions

This study formulated, constructed, and evaluated a preliminary approach for a multi-sensor system based on MRSS technologies for a Tarot x8 UAV. This platform involved the parallel integration of specialized and flexible sensor modules in real-time parallel computing control for UAV environmental data collection.

An exhaustive analysis of the energy consumption behavior was conducted for each sensor module, in order to find efficient energy usage and thus estimate the battery lifetime. The idea is to make efficient use of the batteries via the parallel scheduling of the processors. This scheduling implies that each module works independently in relation to the data capture programmed at a given time.

Additionally, this research focused on how to integrate the multiple sensor modules into the UAV platform. The benefits of this approach could facilitate the adoption of UAVs in the ever-developing field of multipurpose UAV applications such as precision agriculture, search and rescue missions based on acoustic location and detection, fast 3d mapping in real time, and emergency response in natural disasters. Multipurpose UAVs provide powerful multi-modal sensing data information that reduces response times and increases safety, but many of them lack fast mapping capability due to their lack of parallelism in real-time data processing. In real-life teams on the ground, be it in the public safety or humanitarian aid sectors, there is a need for quick and reliable aerial insights to plan and deliver successful operations in remote, complex, and often unsafe environments.

The results of this study serve to enhance the pre-existing advantages of UAVs for decision-making. Furthermore, our work presents a distinctive and innovative input for future development to establish uniformity in data collection. This is accomplished by emphasizing the potential of complete automation in the collection of multi-range data with UAVs.

A management control for a multi-sensor platform which uses parallel computing was proposed. The goal of parallel management is to monitor and control multiple sensor modules to increase their efficiency and reliability and reduce energy consumption in real-time applications. Improved efficiency and reliability has to do with reducing data errors, minimizing outage times, and maintaining acceptable data synchronization with other sensor modules.

Energy consumption is a major concern for UAV technologies. A significant waste of energy occurs due to active sensing, which is typically avoided by turning off the sensor (sleep mode), while no sensing is underway. As future work, an exact energy consumption algorithm for evaluating UAV multi-sensor platforms is required. To assess the lifetime of the power supply (battery) in real time, the energy attributes of the sensor modules must be estimated. Research in this regard has been actively increasing given the wide scope of applications that can profit from such an innovation.

Our approach can greatly enhance the development process of multi-sensor platforms and guarantee mission success by offering a methodical and effortless approach to validate these platforms based on energy consumption. Future research may broaden the scope of this approach to encompass the modeling of multi-sensor platforms and the creation of energy management software. This will be a natural progression of this project. Another future work can involve a multi-sensor data processing (MSDP) software that will be developed as a core module of the data processing system (DPS) for several applications. MSDP and DPS methods will be adopted in order to process data from multiple sensors for any software architecture to support multiple flight missions.

UAV-based multi-sensor platform designers must analyze the energy consumption profile of their application to fully understand the demand and the factors that influence it. Thus, in order to mitigate the impact of frequent battery changes, manufacturers of UAV-based multi-sensor platforms need to understand how the sensor modules consume power while running, which help them estimate battery life