Introduction

At the end of 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection emerged in the city of Wuhan, China, responsible for the current pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)1. The main signs and symptoms are fever, cough, and chest pain, and to a lesser extent dyspnea, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ failure2, which is more severe in adults with multiple comorbidities compared to the pediatric population.

In children, COVID-19 frequently presents asymptomatically or with mild symptoms, without systemic involvement, or requirement of inpatient management in the acute phase1,4. Despite this, available data concerning the sequelae and long-term complications of COVID-19 or post-COVID syndrome (PSC)3,4are still limited. PCS is the presence of a variety of signs and symptoms related to COVID-19 that persists for more than 12 weeks after the diagnosis of the infection has been confirmed5. Prolonged symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection are highly heterogeneous, with an uncertain prevalence in patients under 21 years of age, and without any exact definition in this age group6. However, its most frequent manifestations include fatigue, dyspnea, headache, and neurological affection3,6,7.

Currently, there is scarce medical evidence exploring neurological diseases caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection and PCS8. Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) is a polyradiculoneuropathy associated with a triggering infectious disease 2-1 weeks before the onset of symptoms, which manifests with ascending paralysis and collateral sensory impairment9. Aljomah et al.10 reported a series of 5 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19. The main neurological manifestations, evidenced in a 9-year-old patient, were decreased reflexes in the upper and lower limbs, with a high diagnostic suspicion of GBS. Similar data were reported by Sánchez-Morales et al.11, assessing the likely association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurological symptoms consistent with GBS in 3 of 10 pediatric patients. Although it is recognized that the neurological symptoms associated with SARS-CoV-2, such as muscle weakness or hyporeflexia, are increasingly described in children, a systematic description of the available scientific literature on the subject is necessary. The objective of this exploratory systematic review is to condense the medical evidence that describes the relationship between SPC and GBS in the pediatric population. A systematic description of the available scientific literature on this topic is necessary.

Methods

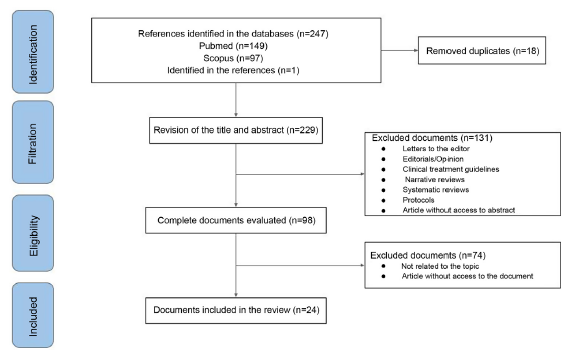

An exploratory systematic review was carried out based on the steps proposed by Arksey and O'Malley12 and adjusted by Levac et al.13, namely: 1) defining the research question; 2) searching for relevant studies; 3) selection of studies; 4) data extraction; and 5) summary and report of results. The review adhered to the elements suggested in the guidelines for reporting adapted systematic reviews for PRISMA-P14 exploratory reviews (Annex 1; Supplementary material). The research question was: what is the available medical evidence on the relationship between GBS and SPC in the pediatric population?

This exploratory review included empirical studies (experimental or observational) published in English and Spanish with data on GBS in pediatric survivors of SARS-CoV-2 infection. It is necessary to clarify that letters to the editor reporting clinical cases related to infection and polyradiculoneuropathy were included. On the other hand, theoretical publications such as literature reviews, systematic reviews, position papers, clinical management guidelines, letters to the editor that do not report cases, as well as documents without access to an abstract or full text were excluded.

Search strategies were designed using Boolean operators and key terms for PubMed and Scopus (Annex 2, Supplementary material). Likewise, references cited in the chosen documents that met the inclusion criteria and that had not been identified through the search strategies were added.

The review of the titles and abstracts of the publications found in the databases was conducted by 2 independent authors (JO and EB), based on the eligibility criteria. Papers with some doubt about their incorporation, the remaining authors met to decide their inclusion or exclusion.

The articles included were reviewed in full text by all the authors, and the following information was extracted in a table: authors, country, year of publication, type of document, type of study, sample size, characteristics of the population studied, objective, journal, and main findings. Subsequently, a narrative synthesis of the most representative publications included in our review was carried out. The references of the included publications can be found in Annex 3, Supplementary material.

Results

Of 263 documents identified by the search, 24 articles were finally included (Fig. 1). The main clinical manifestations presented by the patients were distal and ascending weakness in lower limbs and myalgia. The diagnostic approach was based on clinical findings, spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, and electromyography (EM). In more than 95% (1/24) of the included articles, no genetic material of the virus was found in cerebrospinal fluid. The therapeutic strategy was based on the use of intravenous human immunoglobulins (IVIg), plasmapheresis, and systemic corticosteroids.

Synthesis of the literature exploring the relationship between post-COVID syndrome and Guillain-Barré syndrome

Case reports (n = 15), case series (n = 8), and prospective cohort studies (n = 1) were included, with a total population of 1849 patients. The authors' countries of origin were India (n = 6), followed by Brazil (n = 3), the United States (n = 2), Turkey (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 2), Peru (n = 2), Morocco (n = 1), Egypt (n = 1), Tanzania (n=1), Saudi Arabia (n=1), Colombia (n=1), Chile (n = 1), and Mexico (n= 1). The general characteristics of the documents are found in Table 1.

Table 1 Features of included publications.

| Authors | Type of study | Country | Population characteristics | Purpose | Journal | Main finding/contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanou et al.15 | Case report | United Kingdom | 9-year-old male patient | To determine the association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and GBS | BMJ Publishing Group | A case of GBS with a distal onset involving the lower limbs is presented, with negative serology and biochemistry, except for positive PCR for COVID-19. |

| Krueger et al.16 | Case series | Brazil | Four pediatric patients between 60 days of birth and 16 years | To report neurological manifestations of COVID-19 in children and adolescents | Journal of Neurovirology | 15-year-old boy with GBS who had a good response after IVIg |

| Palabiyik et al.17 | Case series | Turkey | Forty-five patients between 52 days of birth and 16 years | To report the radiological findings of children diagnosed with MIS-C TAC | Academic Radiology | Radiological indings are not diagnostic tools; likewise, an image case with lesions consistent with GBS was reported. |

| Aljomah et al.10 | Case series | Saudi Arabia | Five patients between 28 days of birth and 10 years | To report and identify pediatric cases of COVID-19 with neurological manifestations | eNeurologicalSci | A wide clinical spectrum of neurological manifestations was found in patients with COVID-19, including a case of GBS in a 9-year-old boy. |

| Ray et al.18 | Prospective cohort study | United Kingdom | Fifty-two cases between 1 and 17 years | To analyze the neurological and psychiatric complications associated with SARS-CoV-2 in inpatient children and adolescents | The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health | It was identified that the neurological manifestations associated with MIS-C TAC require intensive care more frequently. Five cases of GBS were reported. |

| Botre et al.19 | Letter to the editor: case report | India | 3.5-year-old male patient | To report the case of a patient with a clinical diagnosis of GBS associated with MIS-C TAC | Annals of Indian Academy ofNeurology | The patient developed GBS one week after testing positive for COVID-19. In children, the disease progresses with rapid recovery if there is a timely diagnosis and treatment. |

| Akcay et al.20 | Case report | Turkey | 6-year-old male patient | To report the clinical characteristics of a child with axonal GBS associated with SARS-CoV-2 | Journal of Medical Virology | The disease course was severe, with rapid progression and prolonged duration of weakness, as expected in axonal GBS. |

| Sandoval et al.21 | Case series | Chile | Thirteen patients between 2 and 16 years | Report the findings of pediatric patients with neurological manifestations associated with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection | Journal of Child Neurology | They found neurological manifestations in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Symptoms resolved as systemic inflammation subsided. A case of GBS was reported. |

| Krishnakuma et al.22 | Letter to the editor: case report | India | Adolescent male patient | To present a case of post-COVID-19 GBS with preserved reflexes | Indian Journal of Pediatrics | The patient preserved deep tendon reflexes, which is consistent with the AMSAN variant of GBS. |

| Curtis et al.23 | Case report | USA | 8-year-old male patient | To present the first case of COVID-19 infection associated GBS D-19 in a pediatric patient reported in the world | Annals of Medicine and Surgery | Ascending weakness was found with electromyography tests that confirmed the diagnosis of GBS. Negative viral test and blood cultures. COVID-19 PCR positive |

| Sánchez- Morales et al.24 | Case series | Mexico | Ten patients between 2 and 16 years | To further investigate pediatric patients with neurological symptoms positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies | Child's Nervous System | Three cases of GBS with positive IgG and one case with positive IgM were also reported. Additionally, an increase in incidence is reported between 2019 and 2020 by a factor of 2.7 |

| Frank et al.25 | Case report | Brazil | 15-year-old male patient | To report a case of progressive and ascending acute symmetrical paralysis related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. | Journal of Tropical Pediatrics | The patient presented mild symptoms, limited to headache and fever, with no respiratory symptoms, and a normal chest CT scan. |

| LaRovere et al.26 | Multicenter case series | USA | One thousand six hundred and ninety-five patients, 365 with neurological involvement, aged between 2.4 and 15.3 years | To understand the range and severity of neurological involvement among children and adolescents associated with COVID-19 | JAMA Neurology | Reported neurological symptoms were transient and life-threatening conditions were rare. The long-term consequences are not known. Four cases of GBS were reported. |

| Araujo et al.27 | Case report | Brazil | 17-year-old female patient | To present the first pediatric case of GBS with the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in the CSF | The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal | This single case of GBS-associated COVID-19, together with the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in CSF, indicates viral involvement inducing inflammation of peripheral nerves. |

| Schult- Montoya et al.28 | Case series | Peru | Five patients between 23 days of birth and 14 years | 5 cases of pediatric patients diagnosed with COVID-19 are reported to describe the initial clinical and neurological manifestations | Peruvian Journal of Experimental Medicine and Public Health | We report a case of a 9-year-old male with ascending muscle weakness and areflexia and positive IgG and IgM for COVID-19 who was treated with IVIg 2 g/kg, with notable improvement in his symptoms upon discharge. |

| Alvarez et al.29 | Case report | Colombia | 8-year-old female patient | To present a case with atypical GBS symptoms associated with confirmed COVID-19 infection | Argentine Neurology | A clinical picture consistent with GBS was reported, related to cerebellar ataxia. Treatment with IVIg 2 g/kg was administered and the patient was discharged with improvement. |

| Khera et al.30 | Case report | India | 11-year-old female patient | To report the probably first pediatric case of GBS and concomitant LETM with confirmed COVID-19 infection | Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal | The patient developed ventilatory failure, for which immunosuppressive treatment was administered, and later IVIg 2 g/kg with significant improvement. |

| Nufez- Paucar et al.31 | Case series | Peru | Five patients between one and 14 years | To present the clinical, radiological, and laboratory characteristics in 5 patients with COVID-19 infection, including one with GBS. | Peruvian Journal of Experimental Medicine and Public Health | Examinations revealed an elevation of lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer, ferritin, and peribronchial thickening. A 13-year-old patient with GBS associated with COVID-19 received plasmapheresis and was discharged. |

| Manji et al.32 | Case report | Tanzania | 12-year-old male patient | To present the first case of post-infectious GBS in a patient with confirmed COVID-19 infection in Africa | The Pan African Medical Journal | It is considered that the offending agent in the case that triggered this neurological event was COVID-19, which caused respiratory symptoms, based on the report of similar cases around the world. |

| Khalifa et al.33 | Case report | Egypt | 11-year-old male patient | To present one of the first descriptions of GBS and SARS-CoV-2 detection association in a child | Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society | Awareness of neuromuscular presentations may be important for early detection of combined or preceding infection with SARS-CoV-2. |

| Das et al.34 | Letter to the editor: case report | India | 7-year-old male patient | To demonstrate the association of SARS-CoV-2 as a possible causative agent of GBS | The Indian Journal of Pediatrics | They report a clinical case of a patient who presented clinical manifestations of GBS; after management in the ICU with mechanical ventilation and IVIg, an antibody test against COVID-19 was significantly elevated. |

| El Mezzeoui et al.35 | Case report | Morocco | 3-year-old female patient | To report a rare case of GBS after infection by COVID-19 in a pediatric patient | Annals of Medicine and Surgery | Demonstrate the importance of early detection of COVID-19 in the pediatric population to avoid extrapulmonary complications, especially those of the CNS. |

| Michael et al.36 | Case report | India | 4-year-old female patient | To report a case of descending GBS post-COVID-19 | Pediatric Neurology | They show a rare case of descending GBS, the importance of their association with the PCS, and the request for tests for the detection of COVID-19. |

| Qamar et al.37 | Letter to the editor: case report | India | 4-year-old female patient | To show the first post-COVID-19 GBS case showing normal nerve conduction | Indian Journal of Pediatrics | This is the first post-COVID GBS study with a normal nerve conduction study, further strengthening the heterogeneity of the disease. |

AMSAN: acute motor and sensory axonal polyneuropathy; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 19; IVIg: intravenous human immunoglobulin; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; LETM: longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; GBS: Guillain-Barré syndrome; MIS-C TAC: pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporarily associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection; CNS: central nervous system; PCS: post-COVID-19 syndrome.

Case reports

Curtis et al.23 reported the case of a 7-year-old male patient with a clinical picture of symmetrical ascending hemiparesis, with subsequent distal paralysis and areflexia. The patient presented respiratory distress requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and management in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Contrast-enhanced MRI of the spine showed enhancement of the posterior cauda equina nerve roots, while the lumbar puncture revealed albumin dissociation without pleocytosis. Likewise, EM showed findings compatible with sensorimotor demyelinating polyneuropathy. The diagnosis was acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) GBS variant, for which management with IVIg 2 g/kg/48 h was initiated. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR, for its acronym in English) was negative for SARS-CoV-2; however, antigens against immunoglobulin G were positive. The authors suggested previous viral infection as a possible etiology, this being the first reported case of GBS after COVID-19 in a pediatric patient.

Araujo et al.27 described the clinical picture of a 17-year-old patient who presented with 48 h of muscle weakness, low back pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Physical examination revealed limb hypoesthesia, symmetric tetraparesis (3/5 in all 4 extremities), and patellar and Achilles areflexia. EM reported demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, while lumbar puncture showed albumin-cytological dissociation (absence of cells and total protein 2.36 g/l), and positive CSF PCR for SARS-CoV-2. RT-PCR tests for SARS-CoV-2 by nasal swab and cerebrospinal fluid were positive for infection. A contrasted MRI of the spine revealed an enhancement of the nerve roots at the cervical level and in the cauda equina. Management was started with IVIg 2 g due to the high suspicion of GBS, with clinical improvement using the Huges disability scale for GBS.

Michael et al.36 reported the case of a 4-year-old girl who had a 2-day history of neck pain, voice changes, and symmetric upper extremity hemiparesis. Family members reported episodes of fever 2 weeks before the onset of symptoms. Physical examination revealed facial diplegia, weakness in cervical movements, and flaccid quadriparesis, predominantly symmetrical and proximal. The patient presented signs of respiratory distress requiring IMV. EM evidenced reduced amplitude of nerve conduction consistent with demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, and contrast-enhanced spinal MRI demonstrated enhancement of lumbosacral nerve roots. Laboratory tests found positive immunoglobulin G antigens for SARS-CoV-2, CSF, and proteinorrachia with a negative viral panel in CSF. The patient was managed with IVIg 2 g, with an adequate clinical course and improvement of symptoms.

Botre et al.19 reported the case of a 3-year-old male patient, with a clinical picture of 4 days of evolution consisting of unquantified fever and self-limited generalized maculopapular rash. However, during his hospitalization, the patient presented a torpid evolution with signs of respiratory distress and elevated inflammatory markers, a picture compatible with the multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children temporarily associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (MIS-CTAC). On the seventh day of hospitalization, the patient presented rapidly progressive symmetric ascending hemi-paresis (upper limb strength 0/5 and upper limb 1/5 added to areflexia), facial weakness, right eyelid ptosis, and ophthalmoplegia. A contrast-enhanced spinal MRI showed enhancement of lumbar nerve roots, while EM revealed early manifestations of GBS, determined by the absence of F waves with reduced nerve conduction amplitude, while the CSF showed proteinorrachia. Management was started with IVIg, methyl-prednisolone, and IMV required for 7 days. After 4 weeks of evolution from his hospitalization, he presented recovery of clinical symptoms.

Case series

Sánchez-Morales et al.25 analyzed 23 pediatric patients, of which 10 (43%) had a diagnosis of active SARS-CoV-2 infection and neurological symptoms. The median age was 11.8 years (IQR: 2-16), with a gender distribution of 1:1. Clinical and imaging diagnosis of GBS was only confirmed in 3 subjects. The authors concluded that the neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 were more common in adolescents and GBS was the most frequent neurological disease after infection; his conduction studies showed a demyelinating pattern and proteinorrachia.

LaRovere et al.26 conducted a study describing the clinical manifestations of 1695 pediatric patients with a median age of 9.1 years (IQR: 2.4-15.3), 54% male, and hospitalized for COVID19. These individuals were classified according to the time of onset of symptoms with the following diagnoses: neuro infection (n = 8), central demyelinating disorder (n = 4), ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke (n = 12), GBS and its variants (n = 4), and severe encephalopathy associated or not with abnormal neuroimaging findings (n= 15). In subjects with a history of neurological disease and neuromuscular disorders, neurological symptoms occurred more frequently. Four patients developed GBS in less than a month of exposure to SARS-CoV-2, with typical clinical manifestations and conduction studies.

Cohort study

In a prospective cohort study, Ray et al.18 described clinical manifestations and neurological diseases in 54 pediatric patients hospitalized in the United Kingdom with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The median age was 9 years (IQR: 1-17) and 58% were male. Patients were classified into 2 groups: individuals diagnosed with a primary neurological or psychiatric disorder associated with active infection or a post-infectious state (52%, 28/54), and subjects with neurological manifestations and a diagnosis of MIS-C. The prevalence of associated neurological complications was 3.8 (95% CI: 2.9-5.0) cases per 100 hospitalized patients.

In the group of patients with neurological or psychiatric manifestations related to COVID-19, the diagnoses were: GBS (n = 5), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (n = 4), other acute demyelinating syndromes (n = 3), and limbic autoimmune encephalitis (n = 1). On nerve conduction or EM studies, 4 of the 5 GBS patients had evidence of a primary demyelinating polyneuropathy. Peripheral neurological involvement in patients with MIS-C was related to systemic inflammatory response and associated tissue damage, in contrast to the COVID-19 neurology group, whose peripheral involvement was of clinical presentation, independent of viral infection. T1-weighted and non-contrast MRI images showed enhancement of the lumbosacral nerve roots consistent with polyradiculoneuropathy. Treatment in both groups was based on IVIg, methylprednisolone, high-dose oral corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibodies. The authors mentioned that neurological manifestations are common in the population under 18 years of age surviving SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Discussion

This exploratory systematic review describes the studies in the pediatric population with GBS secondary to infection by SARS-CoV-2 or PCS. GBS occurred with a high frequency within neurological diseases in patients under 18 years of age, whose main clinical manifestations were distal and ascending weakness in lower limbs and myalgias15-18,20. The diagnosis was made through signs and symptoms, together with imaging findings21-27. The most common variant was AIDP, while medical management with IVIg resulted in adequate clinical evolution in all cases16,28,29.

COVID-19 mainly affects the respiratory system of patients; however, over time, other systems have been involved acutely or in PCS, including the central and peripheral nervous system15,30-33. Although a higher rate of nerve involvement is recognized in the adult population, cases in pediatric patients are increasing due to multiple factors, including delayed vaccination and the association with MIS-C TAC18,33-37.

Neurotropism is common in coronaviruses that affect humans, with reports of GBS cases in pediatric patients after infection by HCoV 229E and OC4338 coronaviruses38. Literature found in this search supports the relationship between infection by SARS-CoV-2 and central nervous system affection, whose pathophysiological mechanisms were mainly due to molecular mimicry and direct neuroinvasion due to the neurotropic characteristics of the virus39. Similarly, the cytokine storm in severe COVID-19 generates a disproportionate immune response and nerve tissue damage in the host. The sum of these pathophysiological mechanisms is responsible for the activation of autoantibodies originated from a cross-reaction of the ganglioside components of peripheral nerves, leading to the subsequent destruction of nerve connections and probably responsible for the progression to GBS39-43.

Among the most common signs and symptoms of GBS associated with COVID-19, ascending and symmetrical muscle weakness, quadriplegia, low back pain, paresis, facial palsy, and deep tendon areflexia are described, explained by peripheral nerve injury resulting from viral tropism15-20,26,27,29.

The main elements for the diagnosis of GBS were clinical manifestations, conduction studies, neuroimaging such as contrasted-MRI of the spine with an enhancement of nerve roots predominantly in the lumbar region, and a cytochemical study of the CSF; in the latter, most of these subjects presented proteinorrachia and albumin-cytological dissociation, without the isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR28,29,32,33. The clinical and imaging recognition of the main characteristics of GBS must be fundamental within the timely diagnostic and therapeutic strategy in primary and specialized care medical personnel so that it has a favorable impact on the rates of neurological sequelae and care burden in the new era of the PCS44,45.

In the studies reviewed, it was found that treatments could vary between IVIg, plasmapheresis, and systemic corticosteroids, schemes used as single or in combination46. The doses used were 2 g of IVIg during the hospital stay, with variable duration (2-7 days), with recovery rates of up to 70%45. Kesici et al.46 described the Zipper method for the management of severe GBS in patients, which consists of plasmapheresis as immunomodulatory therapy followed by IVIg, seeking that plasmapheresis eliminates autoantibodies and proinflammatory cytokines. This method demonstrated a decrease in mortality, need for IMV, and hospital stay; however, it is necessary to assess its impact in patients with GBS and active infection by SARS-CoV-2 or PCS46,47.

Currently, the findings that support a possible causal effect and direct tissue damage of the viral infection in the nervous system are limited27. Studies with a larger pediatric sample size are needed over a long period to differentiate whether the neurological symptoms are clinical manifestations of GBS, secondary to active infection, or a consequence of PCS. Moreover, it is necessary to accurately describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of GBS; for example, Finsterer et al. highlighted a proportional increase in the frequency of this polyradiculoneuropathy secondary to Zika virus infection44.

Limitations

The medical evidence analyzed is mostly descriptive from observational studies type case report, which represents a small number of patients, without control groups and retrospective analyses that prevent precisely establishing a statistical effect. Therefore, analytical observational studies and experimental studies with large sample sizes and long clinical follow-up periods are needed to expand our knowledge about the clinical manifestations, diagnostic images, and laboratory examinations of patients with GBS related to COVID-19 and PCS.

This exploratory review included only 2 databases with publications in English and Spanish, and the search strategy was designed with the help of an expert librarian from the Universidad de la Sabana. An evaluation of the quality of the studies included in this review was not carried out, since it is not an objective described in the PRISMA-ScR guideline12,14.

Conclusions

GBS is an important disease in the pediatric population with active SARS-CoV-2 infection or in survivors. Clinical manifestations and diagnostic and imaging tests are of great importance in timely diagnosis and therapeutic approach, avoiding permanent neurological sequelae in this population group. There are still few case reports, so it is necessary to encourage the development of new clinical studies that improve the medical evidence available in the pediatric population.

text in

text in