Introduction

The mid-2007 economic crisis in the United States critically hit Europe in 2010 and 2012 (Banco de España, 2017).1 The impact of this crisis on film policies or the film industry has seldom been a subject matter in Europe (Arriaza & Berumen, 2015), its countries or regions (Díaz-González, 2016; Díaz-González & Casado, 2017). Nevertheless, some studies relating to the broader realm of cultural policies and the economic crisis have helped frame this research since film policies in Spain form a part of cultural policies.

One of these earlier studies presented data up to late 2009 and early 2010 (Inkei, 2010). Although the data did not reflect the worst times of the European economic crisis, the author had already noted a critical aspect, i.e., that “the scope of the crisis is more varied across Europe than one normally perceives” (Inkei, 2010, p. 98). Other studies support this assertion and show that the initial impact of the crisis on the public funding of culture across Europe was attenuated because Nordic and Central European States had continued to allocate higher proportions of public funding to cultural industries during the crisis period (Rubio Aróstegui et al., 2014; Sand, 2016).

A more recent study has since provided a post-crisis perspective at the European level (Rubio Aróstegui & Rius-Ulldemolins, 2018). It has a strong focus on the Southern European countries that were severely affected by a crisis in public finances (Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) and shows that the limitations and weaknesses of their cultural policies became apparent as austerity resulted in cutbacks in cultural funding.

The choice of Spain as a case study for this research is of particular interest for two reasons. First, Spain is among the top five film-producing countries in Europe. According to the European Audiovisual Observatory (EAO), film production in Europe grew by 47 % between 2007 and 2016. France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK) account for 53.6 % of total film production (Talavera, 2017). Second, Spain was the only one among those top producers that needed financial assistance from the European Union (EU) to cope with the profound economic and social consequences of the crisis.

These data led to the first objective of this study: to ascertain the changes in State film policies that the economic crisis brought about. An important finding on this stage was that State aid for films focused mostly on feature film production. This point gave rise to the second objective: to ascertain how those political decisions are reflected in Spanish feature film production.

Following a presentation of the method and a description of the regulatory framework covering film policies and the economic crisis in Spain, the article introduces film policies between 2007 and 2017 and their consequences for feature film production. The final section lists the conclusions.

Materials and Methods

Although the economic crisis did not hit Spain until 2008, the period covered by this work starts in 2007 to provide a pre-crisis comparison and because Spain’s current Cinema Act was approved in that year. The period ends in 2017 because it is the last year for official data on the film industry. Several events occurring within the Spanish political arena in the first half of 2018 have had collateral effects on the film industry, and the information about them has been included in the article. Due to space limitations, this work focuses on State policies because it is not possible to present the situation of each of Spain’s 17 Autonomous Communities.2

This work required mixed research methods. On the one hand, document analysis and in-depth interviews were used to identify the Spanish State’s public policies applicable to films during the economic crisis. Documentary analysis was used because film policies manifest themselves in laws and regulations, which were exhaustively reviewed as a primary source of data. EU regulations, which Spain had to apply as a Member State, and Spanish legislation were considered (ICAA, 2018). In-depth interviews were deemed necessary to learn about members of the film industry’s opinions and contrast ideas obtained from the documentary analysis. The number of interviews was limited because the goal was to have a tool for complementing and contrasting information, not to conduct research based solely on the film industry’s actors’ opinions. Therefore, a decision was made to interview two film producers, one for non-animated films and one for animated ones,3 and a director of Spain’s Film and Audiovisual Arts Institute (ICAA, for its acronym in Spanish). Film producers were included because keeping film production going was deemed a priority of film policies for the period studied, as noted further on. Film producers were the ones who negotiated with the State administration in that period.

On the other hand, to understand the consequences of film policies on the industry, an analysis was performed of data published in the official sources: the ICAA, Spain’s National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC, for its acronym in Spanish), and the Federation of Audiovisual Producers Associations of Spain (FAPAE, for its acronym in Spanish). If data-based interpretation or deductions created any doubt, queries were raised with the institutions or the audiovisual producers. Every query was answered and resolved. These data were used in the study.

Regarding the sources, the ICAA has two crucial types of published documents: the film yearbook Anuario de Cine (also known as Boletín Informativo) and the annual reports on film aid Ayudas a la Cinematografía. Since 2013, the CNMC has been responsible for publishing the annual report on the fulfilment of the television service providers’ obligation to provide advance funding for European production. Before 2013, that report was published by the Spanish Ministry of Industry. The latest annual report has published data until 2016. For its part, FAPAE publishes an annual report containing industry-specific data.

Regulatory framework of film policies in Spain

The film has come under Spain’s general cultural policy since the restoration of democracy (De la Sierra, 2010). The 2007 Cinema Act is the current legal framework at the State level, embedding the political significance it places on film, as expressed in its preamble:

Film and audiovisual media activity constitutes a strategic sector of our culture and economy. As an artistic manifestation and creative expression, it is an essential element of a country’s cultural identity. Its contribution to technological advancement, economic development, job creation, and the maintenance of cultural diversity are sufficient elements for the State to establish the necessary measures for its development and promotion and determine the most appropriate systems for the conservation and dissemination of film heritage, both within and beyond our borders. Therefore, audiovisual media culture, of which the film is a fundamental part, is present in every sphere of today’s society. (Ley 55/2007, Preamble)4

According to López González (2008) and De la Sierra (2010), this Act is noteworthy for its good legal quality and the broad consensus achieved with the film industry during the drafting thereof. It comprises all the elements of the film value chain and, while its main contents refer to production, it introduces elements relating to film distribution and screening. Besides, it incorporates cross-cutting public policies on education, employment, and equality, for example.

De la Sierra (2010) noted that the model set out in that Act could be deemed a classic European one: it approached film activity from a supposedly cultural angle and consequently proposed a broad range of public aid (Henning & Alpar, 2005). As shown in the presentation of results, the economic crisis significantly impacted the amounts of such aid.

The Cinema Act was partially amended in 2015 due to two factors. First, Spanish laws and regulations had to be adapted to the Communication from the European Commission on State aid for films and other audiovisual works (European Union, 2013). Second, the Spanish government considered that, because of the economic crisis, the film industry was at risk of collapse in the short term (Díaz-González, 2016).

The organisation that plans policies to support the film industry and audiovisual production for the entire State is the ICAA, an independent body (formed in 1984) attached to the Spanish Secretariat of State for Culture that currently reports to the Spanish Ministry of Culture and Sports. Such reporting varies depending on the organisation of Spain’s general State administration, which is determined by the government in office.

Spain and the economic crisis

It is crucial to be aware of the specific impact of the economic crisis on Spain to understand its consequences for film policies. The downturn in the Spanish economy began in the second half of 2008. Between 2008 and 2013, Spain’s GDP saw a cumulative decline of 10 %, with falls in private consumption and investment of 13 and 28 %, respectively, and the unemployment rate reached a record level of 27 % in the first quarter of 2013 (Banco de España, 2017, p. 146).

The year 2012 was critical to the evolution of the economic crisis in Spain, where the recession had intensified due to “the persistent macroeconomic and financial imbalances accumulated in the expansionary phase, the doubts over the soundness of certain parts of the Spanish banking system, and the substantial deterioration of public finances and employment” (Banco de España, 2017, p. 142). The Spanish government5 requested financial assistance from European institutions in June 2012 due to increasing fragility within the banking sector and difficulties in securing funds on international capital markets. Finally, the Memorandum of Understanding on financial-sector policy conditionality between the European Commission and Spain was signed on 20 July 2012. The government then applied strict measures of economic austerity, and there were budgetary cutbacks in all areas, which adversely affected culture and, of course, films (Rubio Aróstegui & Rius-Ulldemolins, 2018).

Most EU Member States needed aid for their respective financial systems due to the economic crisis. However, out of the top film-producing countries, Spain was the only one to receive financial assistance. This fact makes Spain a unique case. The remaining countries within this group-France, UK, Germany, and Italy-received capital aid of 1.1, 3.9, 2.1, and 0.7 % of their GDPs, respectively, while Spain received 5.8 % (Banco de España, 2017, p. 105; Millaruelo & Del Río, 2017).

Results

Film policies during the economic crisis

The most prominent measures of the State policies are related to direct aid for the film industry, tax incentives, value-added tax (VAT), and the obligation to provide advance funding for European audiovisual production.

Direct State aid for the film industry

As already mentioned, the 2007 Cinema Act provided for the introduction of many types of State aids, which were called ‘lines of aid.’ The Act set out 18 different lines of aid and foresaw a gradual increase in public spending of up to €100 million per year to finance them (Díaz-González & Casado, 2017).

However, the actual events were somewhat different. The regulations had to be approved for implementing the Act, but they were not ready until late 2009. Consequently, by 2010-the first year when it would have been possible to open a call for applications for all the lines of aid-the economic crisis had already hit Spain. Figure 1 shows the gradual rise in State funds from 2007 to 2010 and the first fall in 2011, after which the goal of reaching €100 million per year was abandoned. It also shows that the number of lines of aid rose in 2010 (calls for applications were opened for just 12 of the 18 lines of aid provided for in the Act), a trend that continued for one more year only.

Public funds: Figures in thousands of Euros of executed spending (budgeted spending differs from executed spending). Activated lines of aid: The Act provides for 18, depending on budgetary availability. Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from ICAA (2007-17a)

Figure 1 State public funds for lines of aid vs activated lines of aid for film and audiovisual works.

Furthermore, Figure 1 shows the impact of the budgetary cutback policy applied in 2012, as explained previously. A consequence was that the ICAA had to make some decisions and ultimately chose to produce Spanish films, concentrating nearly all its available resources on production aid. This decision had a very significant effect on the film industry because, in practice, most of the resources were allocated to aid for the amortisation of feature films. As shown in Table 1, the funds for new feature film projects were minimal during the period concerned, especially in 2012.

Table 1 Significance of aid for the amortisation of feature films

| Year | Total State funds for aid | Amortisation aid | Aid for new project production | Amortisation aid as a percentage of total State funds for aid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 61,218 | 46,476 | 8,000 | 75.92 |

| 2008 | 67,794 | 50,258 | 10,000 | 74.13 |

| 2009 | 75,793 | 48,498 | 15,000 | 63.99 |

| 2010 | 81,068 | 45,235 | 10,000 | 55.80 |

| 2011 | 70,511 | 41,074 | 8,000 | 58.25 |

| 2012 | 44,475 | 34,455 | 5,231 | 77.47 |

| 2013 | 33,847 | 24,380 | 5,000 | 72.03 |

| 2014 | 61,694 | 53,467 | 3,999 | 86.66 |

| 2015 | 42,245 | 33,590 | 4,747 | 79.51 |

| 2016 | 67,118 | 27,161 | 37,000 | 40.47 |

| 2017 | 70,343 | 31,139 | 35,300 | 44.27 |

Note. Figures in thousands of Euros of executed spending (budgeted spending differs from executed spending).

Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from ICAA (2007-2017a).

These data require an explanation of the existing amortisation aid in the Spanish system. Calls for applications for these aids are opened, and the aid is granted, approximately two years after the commercial premiere of feature films. The aid is automatic, and film producers receive it for recovering part of their investment in films if they meet the conditions set out in the regulations.

An example will help to understand the complex implementation of such aid. Applications can be made for general aid or complementary aid, which is higher. For obtaining complementary aid, a minimum number of points need to be scored. A considerable number of those points depends on the feature film having a minimum cost recognised by the ICAA and a minimum number of viewers. For most films, the minimum cost must be €2 million, and the minimum number of viewers must be 60,000. If these figures can be corroborated, the producer gets all the corresponding points (each point equals €10,000 in aid); if they do not reach those figures, the producer gets nothing. The film Lo imposible/The Impossible (Bayona, 2012) obtained €1,044,195.90 in amortisation aid; the cost recognised by the ICAA was €30,324,580.13 (ICAA, 2007-2017a), and the number of viewers at the box office one year after its premiere was 6,078,377 (ICAA, 2007-2017b). Amortisation aid has a limit of €1.5 million. This film received a lower amount because it was shot in English and not in one of Spain’s official languages.

A major consequence of this system is that producers assume a very high risk because they must advance, usually through bank loans, part of the cost of a film that they trust they will recover later through amortisation aid. Producers trust that they will recover their investment without knowing how viewers will welcome the film and what funds will be allocated to such aid two years after the premiere.

The Spanish State had to maintain such aid, even when it had decided to make the 2012 cutbacks, to prevent negative economic consequences for producers and the banks that had financed their projects. In 2014, for example, when the policy of reducing funds for films was in full flow, the allocation to amortisation aid increased by 101.92 % compared to 2013 (see Table 1). The reason for this was the need for ensuring that aid for all the films that met the conditions was covered to avoid the film industry’s collapse. Total State funds allocated to aid for film and audiovisual works were €61.664 million, €53.467 million of which were allocated to amortisation aid (86.7 %).

Between 2007 and 2016, 1,403 Spanish feature films premiered, and 663 subsequently received amortisation aid. The latter figure represents a little over 47 % of the total, proving the productions’ dependence on such subsidies. This aid was repealed in 2019. As already explained, the Cinema Act was amended in 2015, and the removal of amortisation aid was one of its salient points. This after-the-event aid system poses many problems, worsening during the economic crisis (Díaz-González, 2016). Table 1 reflects this amendment. Aid for new feature film projects increased from 2016 because aid after a film’s premiere was no longer available.

Tax incentives

Tax incentives for investment in the production of feature films and television content were also the focus of policies during the economic crisis. In 2013, representatives of the sectors involved stated that such incentives would have to reach 25-30 % to attract investment capital outside the audiovisual business and enable the Spanish film industry to compete.

The Corporation Tax Act (Ley 27/2014) was approved in 2014. Its provisions established 20 % tax relief on the first €1 million invested in production and 18 % on the rest of the investment. The maximum amount of such relief was €3 million. The Act also established tax relief on foreign productions filmed in Spain: 15 % of expenditure on Spanish territory if such expenditure was at least €1 million. For such productions, the maximum amount of tax relief was €2.5 million.

These tax incentives did not fulfil the industry’s expectations because of the economic crisis and the State’s need to collect taxes. However, it should be said that tax relief on foreign productions of feature films was something entirely new in Spain and a welcomed decision for the industry.

Better tax incentives came in 2017. Tax relief on production investment went up to 25 % on the first €1 million and 20 % on the rest of the investment. Tax relief on foreign productions went up to 20 % of expenditure on Spanish territory, and the maximum amount of tax relief went up to €3 million.6 The Spain Film Commission welcomed this change and asserted that closer alignment of Spain’s tax incentives with those existing in other parts of Europe was a significant step forward in increasing Spain’s competitiveness as a destination for international film shootings and television series (Audiovisual 451, 2017). For example, tax relief on foreign film shootings is 25 % in the UK and 30 % in France.

Value-added tax

The value-added tax was also the focus of adjustments by the Spanish government in 2012 to deal with the economic crisis (García-Enríquez & Echevarría, 2018). On 1 September of the same year, the general VAT rate went up from 18 to 21 %, and there were several changes to the classification of some goods and services, meaning that they were moved from the reduced rate (8 %) into the general rate (21 %) category. Among the services affected by that rise were films that could be screened, plays, and concerts. This so-called ‘cultural VAT’ increase was very unpopular and provoked considerable protest from the film industry. However, studies focusing on the effects of that measure on box-office numbers and receipts have yet to be conducted.

The work by García-Enríquez and Echevarría (2018) applies to all cultural services affected by the increase in VAT-shows (including cinemas), museums, Internet, radio, and TV licenses-. They concluded that higher income levels were associated with higher levels of expenditure on cultural items. However, for those with lower income levels, such expenditure represented a higher proportion of annual income and, consequently, had a more significant impact on household budgets (pp. 20-30). As an overall finding, they asserted that the 2012 VAT reform could be considered regressive, though the reduction in households’ well-being depended on the inequality aversion in the distribution of households’ cultural expenditure. These authors added:

Regardless of such inequality aversion, it cannot be determined whether the VAT reform would have diminished or raised inequality in the distribution of cultural spending among Spanish households when compared with the pre-reform distribution. When relating the VAT reform effects to households’ incomes, the relative effects of the reform do not seem sizable, as cultural expenditure in Spanish households represents a quite low proportion of total expenditure: a mean of 2.63 % and a median of 1.96 %. (García-Enríquez & Echevarría, 2018, p. 30).

In mid-2017, VAT on live shows (performing arts, concerts) was cut from 21 to 10 %. In late 2016, the governing party (the conservative Partido Popular) had committed to reducing it to secure the support of Ciudadanos, a centre political party, to carry on governing. Finally, the reduction of VAT from 21 to 10 % on cinema tickets came in July 2018. The General State Budgets for 2018 did not come into effect until then, thereby delaying the application of that measure, which had been announced months earlier.

Obligation to provide advance funding for European audiovisual production

Audiovisual media service providers operating in the EU Member States must provide advance funding for the European production of cinema films, television series and films, documentaries, and animated series (Directive 2010/13/EU) on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulations or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services. In Spain, funding characteristics were amended in 2010 (Ley 7/2010, Section 5.3). Before 2010, it was met by investing in cinema feature and short films and television films. Under the 2010 amendment, the obligation could also be fulfilled by investing in television series or miniseries and animated series (see Table 2).

Table 2 Characteristics of the obligation of television service providers to fund film and audiovisual productions

| Private | Public | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment share (% of accrued income in the previous financial year) | 5 % | 6 % | ||

| Destination of obligatory investment | By production type | Cinema feature films | Minimum 60 % | Minimum 75 % |

| Television films or miniseries | Maximum 40 % | Maximum 12.5 % | ||

| Television series | Maximum 12.5 % | |||

| Reserve for independent productions | Minimum 50 % | |||

| Reserve for works in Spain’s official languages | Minimum 60 % | |||

Source: Taken from Díaz-González & Casado (2017, p. 178)

This change was a political concession to the television industry because, if the regulations allowed them to justify part of their obligatory investment by funding series, it would be advantageous. Spanish series are prime-time staples for television networks, and television companies cannot forego investment in such contents; so, if they can allocate to series part of the amount that they were previously compelled to invest in films, then the measure is beneficial to them (Segovia et al., 2011). Conversely, this change is not favourable for the film industry, which is very dependent on support from television groups to take their projects forward. Since the amendment, it has lost part of the obligatory investment to the television industry.

Besides, since the amendment of the Cinema Act referred to earlier,7 there is a sliding scale for granting State aid to produce feature films in the project stage. The economic and financial viability of feature films is one of the aspects scored. Having contracts or firm commitments with audiovisual media service providers or their subsidiary production companies operating in Spain is the aspect that scores the highest.

Consequences for feature film production

The identified consequences of these policy changes for the Spanish film production are those connected with the number of feature films produced and their genre (fiction, documentary, or animation), the evolution of the mean cost of feature films, and the influence of funding from television networks.

Feature films produced: number and genre

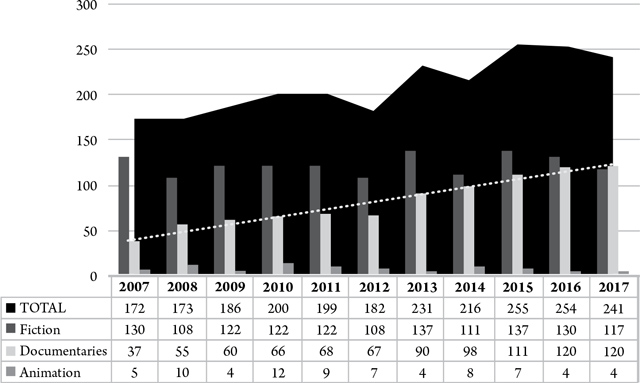

The results show that the rate of feature film production in Spain did not fall during the economic crisis years (see Figure 2).

Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from ICAA (2007-17b).

Figure 2 Number of Spanish feature films produced by year (2007-2017)

However, it is necessary to know the breakdown by genre to understand what happened to film production (Figure 3).

Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from ICAA (2007-17b)

Figure 3 Spanish feature films produced: Total and distribution by genre. Trend line for documentaries.

Documentaries represent a high percentage of film production. In 2007, before the crisis, this genre accounted for 21.5 % of total production; a year later, it accounted for 31.8 %. There was an upward trend during the economic crisis period, and, from 2013, the percentage increased significantly, as shown in Figure 3. In 2017, documentaries accounted for 49.8 % of total Spanish film production. Documentary productions have lower costs; their cinema screenings are more limited (they take place on less commercial circuits, with fewer copies and shorter time on the listings), and, in many cases, their commercial approach is minimal or non-existent.

Evolution of the cost of feature films

Although the total production figures were higher, the mean cost of feature films fell during the economic crisis period. Available official sources enable this statement to be backed up from several perspectives.

In its annual reports, FAPAE (2009-2016) published the data shown in Figure 4. Although the mean cost in 2016 rose after seven years of falling costs, it is necessary to wait for the data of subsequent years to be published in order to know whether a change in trend has occurred. Notwithstanding, the mean cost in 2016 was still much lower than in 2009.

Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from FAPAE (2009-16).

Figure 4 Mean cost of feature films produced (2009-2016) in millions of Euros.

The ICAA (2007-17b) has also published data on the mean cost of feature films. To arrive at the figures, it considered a sample of feature films: those with a total cost higher than €900,000 and those whose cost was recognised by the ICAA for the respective year. Films whose cost has been recognised are usually those that have received State aid, although the number could be higher because any producer can ask for official recognition of the cost. The 2007-2017 data are shown in Figure 5.

According to these data, the mean cost fluctuated during the economic crisis period; there was no continuous fall or rise. However, as shown in Figure 5, the cost ranged between €2.3 and €3.2 million. These amounts are low for producing a blockbuster feature film and reflect the types of projects that the Spanish film industry could bring to fruition.

Source: Own elaboration with data retrieved from ICAA (2007-17b).

Figure 5 Mean cost. Sample of feature films with a cost higher than €900,000.

Television networks and film production funding

Fernández-Blanco and Gil (2018) published an evaluation of the obligation to provide advance funding for film production before the economic crisis. They established a correlation between box-office success and TV participation in Spain’s film production between 2000 and 2008. As a result, they do not reflect the consequences of the previously described changes in film policies.

They inferred from their results that,

Private and public TV networks follow very different behaviors […]: private networks select projects that are more likely to be successful in the local exhibition market, while public networks select projects that are more idiosyncratic and therefore less likely to be successful in front of large audiences in the Spanish market. This means that this type of regulation is operative both to encourage industry development through market-oriented products and products satisfying other artsy and cultural criteria (Fernández-Blanco and Gil, 2018, p. 420).

The data from 2008 show that, between that this year and 2016, 53 % of all feature films produced in Spain received aid from television service providers. The aid they received took the form of direct participation in the production, the purchase of broadcasting rights, or both.

For the same period, a sample of the top ten feature films at the box office premiered in each of the respective years was selected. This sample of 90 feature films showed that, for their production, 56.7 % of them had had direct investment from a private television company. The State public television broadcaster (TVE) only invests by buying broadcasting rights. More than 50 % of feature films (in terms of total production and success at the Spanish box office) were produced with investment from television networks, which may signal that the film industry is financially heavily dependent on the television industry.

Within the film industry, there are different assessments of such dependence. The ICAA interprets that relationship as a positive consequence of the application of film policies. For example, in its assessment of the effectiveness of the obligation to invest in a film, it asserted that the contribution made by television service providers, through the purchase of exploitation rights or their participation as a co-producer, represented an undeniable annual boost for production funding. Furthermore, it noted that the top five Spanish films at the box office in 2016-Un monstruo viene a verme/A Monster Calls, Palmeras en la nieve/Palm Trees in the Snow, Villaviciosa de al lado/A Stroke of Luck, Cien años de perdón/To Steal from a Thief, and Cuerpo de élite/Heroes Wanted-involved providers who were under the obligation to invest in a film (CNMC, 2018, p. 53). The ICAA added that, from an economic perspective, the role of television networks in film production was vitally important since it represented an overall funding figure that was higher than either State subsidies or box-office receipts (CNMC, 2018, p. 56).

However, some producers felt that the policies adopted during the economic crisis increased that dependence. They saw the need to have a contract or firm commitment with audiovisual media service providers-a condition for applying for State aid for production-as a drawback, which they believed only favoured more commercially orientated projects. According to producer Chelo Loureiro,

It is challenging for most projects to meet this condition. Having a firm commitment from RTVE is difficult because the way the public [broadcasting] corporation works means it takes a long time to decide on which projects to support. And the private [media] groups with greater funding capacity (Mediaset España and Atresmedia) want a very commercial type of film, and they are entitled to demand it (Chelo Loureiro, 2016, personal communication).

Conclusions

Concerning the first objective of this article-to ascertain the changes in State film policies in Spain during the economic crisis-the results suggest an apparent contradiction in these policies. The contradiction lies in the Spanish government’s intention to make major cutbacks in film funding in 2012 and the political commitment needed to maintain such aid and prevent the total collapse of the Spanish film industry. An example of this contradiction is the increased allocation of amortisation aid within the General State Budget by almost 102 % in 2014. As stated, 1,403 Spanish feature films premiered between 2007 and 2016, and 663 received amortisation aid, a little over 47 % of the total, showing the productions’ dependence on such direct aid.

The article also points out the probable positive consequence of changes in tax incentives in 2017. For foreign productions shot in Spain, tax relief went up to €3 million, in closer alignment with existing tax relief policies in other European countries. This change might increase Spain’s attraction to foreign producers as a destination for international film and television series shootings and give the industry a competitive boost.

A controversial change in existing film policies was the increase in the VAT rate. After the 2012 amendment to the law, cinema tickets were subject to the general rate of 21 %, an increase of 13 percentage points from the previous VAT rate (8 %). Due to political compromises and the unpopular measure, VAT on tickets was reduced to 10 % (from the previous 21 %) in July 2018, closing a policy change circle. As the VAT rate has only recently been cut, the effects of the 2012 increase on box-office numbers and attendance have yet to be established.

This research also identifies the consequences derived from the obligation to provide advance funding for European audiovisual production. The amended 2010 Act broadened the range of works that could be subject to the obligation to include television series or miniseries and animated series. The measure clearly benefits television networks by allowing them to fund content they can subsequently use to fill their airtime. Conversely, the measure has negative consequences for the film industry, which is already heavily dependent on television groups’ support to take their projects forward. This dependence further increased in 2016 after the amendment of the Cinema Act, in which State aid for production at the project stage was linked to its financial viability. A contract or firm commitment with a television network or its production companies ranked high in the granting scale.

The second objective was to ascertain how the political decisions were reflected in Spanish feature film production. In this respect, one of the main findings was the increasing number of feature films produced and the predominance of documentaries over fiction and animation. In 2007, documentaries accounted for only 21.5 % of total Spanish film production, while in 2017, they accounted for 49.8 %. This finding may partly explain the falling mean cost of feature films during the economic crisis. In 2009, the mean cost of feature films produced was €3 million and, in 2016, it went down to €1.6 million. Documentaries usually have lower costs. From 2007 to 2017, and according to the ICAA sample of feature films produced with a cost higher than €900,000, the mean cost of feature films produced ranged between €2.3 and €3.2 million. The data obtained suggest that further research is needed to conclude that these figures are low for producing a blockbuster. Nevertheless, the figures are low enough to prevent funds from being allocated to print and advertising (P&A). Small P&A funds may hinder films’ access to national and international distribution.

Regarding the consequences of changes in film policies for Spanish feature film production, another finding is the surprisingly different perception of film production’s considerable dependence on funding by television networks. Data analysis shows that more than 50 % of the feature films produced between 2008 and 2016 (in terms of total production and success at the domestic box office) received aid from television networks. This percentage shows the level of economic dependence of film-industry production on them. The different points of view on the effectiveness of the application of film policies are worthy of note. While the ICAA, the State film authority, regarded the relationship as positive (i.e., the contribution made by television networks-through the purchase of exploitation rights or their participation as co-producers-was an undeniable boost for production funding), some producers felt that the relationship was negative. The reasons those producers gave was that the Spanish public broadcasting corporation (RTVE) was slow in its decision-making and that private media groups wanted to fund a more economically efficient, commercial type of content.