In 2010, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) proposed the Strategic Plan for Biological Diversity 2011-2020 to significantly reduce the current rate of loss of biological diversity, called Aichi Targets. This Plan, established as Target 11, achieve with protected areas and other effective area-based measures an area 17 % of terrestrial and continental waters, and 10 % of coastal and marine areas; the areas should be systems managed effectively and equitably, ecologically representative and well- connected, and integrated into broader landscapes and seascapes (CBD, 2010).

The ecological representativeness of a system of protected areas is given if there is an adequate sample of biodiversity at different levels of biological organization (genes, species, communities, and ecosystems), which guarantees ecological processes and their long-term viability (Stevens, 2002; Dudley and Parish, 2006; Barr et al., 2011). The representativeness is recognized as a key attribute for conservation planning (Margules and Pressey, 2000). Although there is no consensus on what percentage each element of marine biodiversity should be represented within a system, scientific evidence from different models and empirical studies suggests that between 20 % and 50 % of each ecosystem or habitat should be guaranteed to meet multiple objectives for the conservation of MPA (Sala et al., 2002; Aírame et al., 2003; Gell and Roberts, 2003; Gaines et al., 2010; O’Leary et al., 2016).

Colombia has a National System of Protected Areas (SINAP, in its Spanish acronym) with 35 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that are part of the MPA Subsystem (SAMP). This subsystem contains 17 sub-national MPAs, administered by subnational environmental authorities of the Caribbean and the Colombian Pacific. Likewise, it has 16 MPAs of the System of National Natural Parks (SPNN, in its Spanish acronym), which is the set of areas with exceptional values for the national heritage that, due to their natural, cultural, or historical characteristics, are reserved and designated in any of the existing categories (Decree 2811, 1974), and administered by National Natural Parks of Colombia (PNNC, in its Spanish acronym). Currently, the MPAs of the SPNN is divided into three management categories: 1) National Natural Park (NNP), 2) Via Park (VP), and 3) Sanctuary of Fauna and Flora (SFF). Besides, two National District of Integrated Management (NDIM) are not part of the SPNN. However, the delegation of the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADS, in its Spanish acronym) is administered by PNNC. This study includes the two NDIM within the SPNN, given the planning and management effort carried out by the PNNC.

In 2010, an analysis of ecological representativeness gaps was carried out at the marine and coastal ecosystems for 13 areas of the SPNN (Segura-Quintero et al., 2012). The objective of this study is to evaluate a decade later the progress and contribution made by the MPAs managed by PNNC (Table 1), to the representativeness of the SAMP and Aichi Target 11, within order to suggest future conservation efforts of the country and contribute to the discussion of the construction of the new goals for Colombia in the post-2020 CBD framework.

Table 1 Marine protected areas managed by National Natural Parks of Colombia with their corresponding management categories and equivalence with the categories of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). NNP: National Natural Park. VP: Via Park. SFF: Sanctuary of Fauna and/or Flora. NDIM: National District of Integrated Management. The coverage areas correspond to the official values designated in the administrative Act (Designation Resolution).

Five of the evaluated MPAs do not have marine coverage (SFF Los Flamencos, NNP Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, SFF Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, NNP El Corchal Mono Hernández, and NNP Sanquianga). Still, they are taken into account in the analysis as they contain coastal ecosystems such as beaches, cliffs, estuaries, and mangroves.

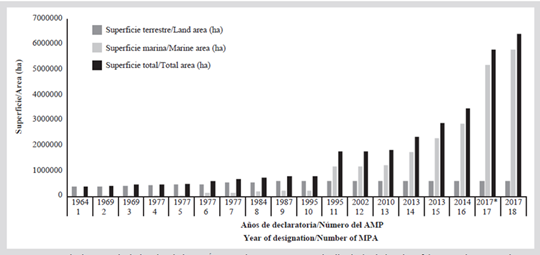

Figure 1 shows how until 2010, when 13 MPAs were designated, the marine protected area coverage corresponded to 1 216 414 ha, equivalent to 1.4 % of the country’s total marine coverage. With the subsequent designation of five new MPAs and the expansion of the SFF Malpelo in 2017 (Table 1) a coverage of 5 977 804 ha was achieved, equivalent to 6.7 % of the country’s current total marine coverage. This increase in protected marine coverage, together with the 17 MPAs at the sub-national level (12 612 213 ha), allowed Colombia to meet and exceed the 11 Aichi Target of the CBD, achieving 14 % the marine area in MPAs (MADS and UNDP, 2019).

Figure 1 Timeline in the designation of the 18 Marine Protected Areas managed by National Natural Parks of Colombia. Sum of the land, marine, and total surface of the areas. *Extending surface of the marine area of the SFF Malpelo (1 709 404 ha), it was approved in 2017 (MADS Resolution 1907, 2017). The number of MPA corresponds to Table 1.

The tool used to make the analysis was a geographic web application called the Colombian SAMP Decision Support System (DSS-SAMP) (http://gis.invemar.org.co/ssdsamp) having the Marine Environmental Information System (SIAM) (https://siam.invemar.org.co/) and the National Single Registry of Protected Areas (RUNAP) (https://runap.parquesnacionales.gov.co/) as the primary information providers. It is supported by a heterogeneous technological environment with Linux and Windows operating systems (Centos 6 and Windows Server 2018R2), ArcGISServer mapping server (v. 10.3.1), Python programming languages (v. 2.7), Java (v. 1.7.0_21-b11), and Javascript (v. Jquery 2.1.4 and ArcGIS API for Javascript 3.16), Oracle Database Engine (v. Oracle Database 11g Release 11.2.0.4.0 - 64bit Production) and Geodatabase (v. 10.3.1) (Bohórquez et al., 2010; Segura-Quintero, 2019). This DSS makes it possible to evaluate the SAMP’s representativeness hierarchically between the MPAs of the national and sub-national management. The tool records how much of each marine and coastal ecosystem’s surface is under protection in each MPA, assuming precision according to the scale on which each one is mapped (Segura-Quintero, 2019).

For the analysis, 11 marine and coastal ecosystems were selected for the Caribbean and 11 for the Pacific. The source of cartographic information for the ecosystem used by DSS-SAMP can be consulted directly from SIAM and is at a scale of 1:5000 to 1:100000, except the seabed geoforms scale 1:500000. The representativeness ranges were used equivalent to those used in the 2010 analysis (Segura-Quintero et al., 2012), adjusting the names according to the last analysis performed for SINAP in the land component (SINAP, 2019). The ranges are expressed as a percentage of the extension or coverage of the ecosystem within the SPNN, as follows: Overrepresented or Or (≥ 60 %), High representativeness or Hr (30-59 %), Medium representativeness or Mr (10-29 %), Low representativeness or Lr (< 10 %) and No representativeness or Nr (0 %).

In Figure 2A it is observed how in the last ten years, the Caribbean presented an increase in the representativeness of ecosystems such as mangroves (1.5 %), seagrasses (2.3 %), sedimentary bottoms (2.9 %), sandy beaches (4.3 %), saline beaches (5.6 %) and deep-sea coral formations (64.7 %). However, the representativeness of coastal lagoons and estuaries remains static. They continue to be categorized as Lr, despite being considered nursery ecosystems, critical for the life cycle of many species of fish and invertebrates by providing them with habitat, shelter, and food (Beck et al., 2001; Sheaves, 2009; Nagelkerken et al., 2015), also their function and value is conferred by the mosaic of habitats with which they interact (seagrasses, mangroves, and corals) (Sheaves et al., 2015). An Lr is also observed for the estuarine ecosystem when including sub-national MPAs in the SINAP analysis (SINAP, 2019). The inclusion to the SPNN of a new ecosystem such as the deep-sea coral formations is highlighted when a new MPA was designated in 2013 (NNP Corales de Profundidad), identified by selection exercises of conservation priorities (Alonso et al., 2007, 2008, 2010) and gap analysis for representativeness in 2010 (Segura-Quintero et al., 2012).

For the Colombian Pacific, the representativeness of ecosystems such as estuaries (2.7 %), sedimentary bottoms (3 %), mangroves (3.1 %), intertidal mudflats (3.2 %), sandy beaches (8 %), and seamounts (8.5 %) increased (Figure 2B). It is observed that in the last decade, the representativeness in the mixed guandal forest has not improved (0.5 %), considered an essential ecosystem due to the great richness of plant species that are in close association with the mangrove forest strip in the Pacific of Colombia (del Valle, 2000; Álvarez-Dávila et al., 2016). This mixed guandal forest trend was also observed in the SINAP analysis that considered the sub-national MPAs (SINAP, 2019). The increase in the seamounts (Malpelo and Yuruparí ridges) as a conservation target or a substitute for biodiversity within the SAMP is highlighted (Codechocó et al., 2014; Alonso et al., 2015). Recent global evaluations show that although geoforms such as submarine mountains and canyons, escarpments and abyssal hills have high biodiversity values (Morato et al., 2010; Kvile et al., 2014; Durden et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2018), they are not well represented in national MPA systems (Fischer et al., 2019).

Figure 2 Changes in the representativeness of marine and coastal ecosystems in marine protected areas managed by National Natural Parks of Colombia from 2010 to 2020. A) Colombian Caribbean. B) Colombian Pacific. Representativeness ranges: Overrepresented -Or (≥ 60 %), High representativeness -Hr (30-59 %), Medium representativeness -Mr (10- 29 %), Low representativeness -Lr (< 10 %) and No representativeness -Nr (0 %).

By 2020, an improvement is observed in the representativeness ranges of ecosystems in the SPNN (Table 2). The only Nr ecosystem (deep-sea corals) change to Or, decrease the number of ecosystems in Lr, and increased the number to Mr. The representativeness increased when the sum of Mr, Hr, and Or went from 59.1 % in 2010 to 68.2 % in 2020. However, these results do not pretend to fulfill the representativeness’s target exclusively to the SPNN, but rather to identify how much the contribution to SAMP and complement the goals with sub-national MPAs, which were not the subject of this study.

Table 2 Representativeness ranges of marine and coastal ecosystems in the System of National Natural Parks and their variation between 2010 and 2020 in Colombia.

The most significant conservation effort in MPAs of the SPNN and general of the SAMP has been concentrated on the continental shelf (≤ 200 m), which is only equivalent to 6 % of the jurisdictional waters of Colombia (Exclusive Economic Zone) (Invemar, 2020), but is in these environments where the greater scientific knowledge of biodiversity has been gathered (Costello et al., 2010; Miloslavich et al., 2011). Therefore, Colombia must incorporate the high biodiversity values associated with deep benthic habitats (Harris and Baker, 2012), without creating large MPAs with low biodiversity and little threat, as has happened in other regions of the world to meet commitments to the CBD (Williams et al., 2009; Devillers et al., 2015). The challenge of improving this representativeness should fall on MADS as a National Environmental Authority, which could delegate its administration to PNNC for its experience with remote or oceanic areas. According to Fisher et al. (2019), the inclusion of deep benthic habitats in MPAs has begun to be recognized globally, finding that of 230 countries evaluated, 74 included submarine canyons, and 38 included seamounts. Given the growth of offshore productive activities such as mineral extraction, trawling, oil, and gas exploitation (Davies et al., 2007; Ramírez-Llodra et al., 2011; Cordes et al., 2016), among others, Colombia should explore the application of new management categories such as Natural Reserve and Unique Natural Area proposed by the IUCN (Categories I and III, respectively, Dudley, 2008). Those categories have been designated in the last decade in countries such as the USA, Canada, and France for this type of deep habitats environment (Fernández-Arcaya et al., 2017). A recent case was the designation in USA of the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument (Category III-IUCN) (Costello, 2019; Auster et al., 2020). A next challenge to advance in planning for the country’s marine conservation is to include in the representativeness analyzes the level of biological organization of species and to incorporate as an attribute of the SAMP the connectivity criteria (functional and structural) (Balbar and Metaxas, 2019), taking as core the MPAs of the SPNN. However, it is crucial to conceptualize even more about this aspect (SINAP, 2019).

In the process of building the global framework for biodiversity post-2020, the CBD proposes to increase to 30 % the protected land and sea surface by 2030, either by protected areas or other effective area-based conservation measures (CBD, 2018). This new global goal seems to be a correct work path (O’Leary et al., 2016; Woodley et al., 2019), after the recent diagnosis of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services (IPBES, 2019). It was identified that the most important direct drivers of biodiversity loss are habitat fragmentation and loss (changes in the use of land and sea) and direct exploitation, with the overexploitation of fishery resources being the most important in marine systems. Moreover, the assessment reported that 66 % of the ocean surface experiences an increasing cumulative impact, and more than 85 % of the wetlands have disappeared (IPBES, 2019). Additionally, a recent multisector financial analysis (including agriculture, forestry, fishing, and conservation) estimated a higher production (income) by expanding protected areas to 30 % on the planet, being able to generate between $ 64 to $ 454 billion dollars per year by 2050, even after the possible economic effects that it is generating to recovery from the effects of COVID-19 (Waldron et al., 2020).

It is essential for Colombia, with her coverage of 50 % of marine territory (Invemar, 2019), to take advantage of the different international scenarios, facing the future conservation of the oceans, such as: 1) The construction of the new post-2020 framework of the CBD, where Colombia should support the target of 30 % to 2030, but efficiently guaranteeing a balance between coverage and representativeness of the SAMP; 2) Colombia, through its experience, can support the debate and the definitions that are developed in the draft “Framework Agreement of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, relative to the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction” (ABNJ) (UN, 2019), where one of the main points is the management of area management tools, including MPAs; and 3) The proclamation of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development (2021-2030), by the United Nations General Assembly (UN, 2020), recognizing science as a pre-requisite for sustainable managing of the ocean, and a fundamental pillar for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda and mainly the SDG 14 Life Below Water.

Based on the above, it can be concluded that: 1) the contribution of the MPAs managed by PNNC to the representativeness of marine and coastal ecosystems of the SAMP improved by 2020, in some strategic ecosystems such as seagrasses, mangroves, sandy beaches, and the inclusion of a new ecosystem such as deep-sea corals, specifically in the Caribbean. The opposite was for mixed guandal forest in the Pacific and coastal lagoons and estuaries in the Caribbean. However, meeting the goals does not lie exclusively with the SPNN since there are 17 sub-national MPAs. This analysis only allows us to understand the 18 MPAs of the national management scope. 2) The need to increase research and knowledge of deep benthic habitats is noted to include them in conservation priorities and the analysis of gaps in SAMP representativeness. 3) Colombia should take advantage of international dialogue scenarios to contribute and commit to ambitious CBD conservation goals (30 % by 2030) and support the declaration of possible MPAs in ABNJ based on their experience with the designation and management of oceanic MPAs (SFF Malpelo and NNP Deep-sea Corals).

text in

text in