INTRODUCTION

Boca de la Barra area is located to the west of Salamanca Island and is currently the only permanent connection between the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta (CGSM) and the Caribbean Sea. This water body (CGSM) has an extension of 450 km2, and it is recognized at the world, national, and regional levels for being included in five conservation figures, among which there is its declaration as a RAMSAR (1998) wetland and biosphere reserve (2000) (Vilardy-Quiroga and González-Novoa, 2011). For this ecosystem, Boca de la Barra is the point of interaction between the internal circulation dynamics of the lagoon complex and the coastal processes of the adjacent shallow platform. It has an average width of 210 m, and depths in the channel of up to 6 m (Invemar, 2015b). Water inlets run through the channel from and to the marsh, which flows are controlled by the tide and transport flows, which are between 200 m3/s and 700 m3/s according to the time of the year (Invemar-Corpamag, 2018). This is to say that those flows are also conditioned by the complex hydrologic dynamics originated in the Magdalena River’s contributions to the flood plain, which finally arrive at the lagoon complex, with discharges on the main marsh stemming from rivers that drain the western watershed of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNSM), one of the major sources of sediment inputs originated by the geological characteristics of this coastal relief (Cardona et al., 2010).

In this context, the morphological behavior of Boca de la Barra plays an important role in the hydric and sedimentologic exchange dynamics, which are fundamental for the functioning of the ecosystem and the advanced rehabilitation processes carried out after the environmental deterioration caused by the building of the Ciénaga-Barranquilla and Palermo-Sitio Nuevo roads in the 1950s and 1970s, respectively, which effects were mangrove loss, decreased biodiversity, hyper-salinization, reduced hydrobiological resources, and a broken hydric balance in the whole system (Gónima et al., 1998; Botero and Salzwedel, 1999; Polanía et al., 2001; Rivera-Monroy et al., 2006). Since the opening of the channel, the coastline has been subjected to complex coastal dynamics, as it is completely exposed to the direct action of oceanographic and climatic processes along the Salamanca Island (Martínez and Molina, 1992; Gómez et al., 2017).

On the other hand, studies on the dynamics of Boca de la Barra from a morphological point of view are scarce. The one conducted by Erffa (1973) stands out, which describes the multitemporal monitoring of the coastline during the channel configuration process under the conditions of a variable flow regime and the effect of protection works in the mouth, recording short-term changes (erosion/accretion) of up to 10 m after the construction of the Ciénaga-Barranquilla road. Bernal (1966) described the natural mouth’s change of position in 1953, 1987, and 1993, finding morphological indicators of a trend towards erosion on the west side and accretion on the east side. Other recent studies are those conducted by Invemar, which provide knowledge on hydrological, sedimentologic, bathymetric, climatic, and oceanographic aspects (Invemar-GEO, 2015, 2016, 2017). Likewise, there is progress in the implementation of a hydro-sedimentologic model of the lagoon complex, with the aim to understand water flow and sediment dynamics according to the hydrological and tidal conditions (Invemar-Corpamag, 2018). Finally, studies and projects aligned with the CGSM rehabilitation approaches are based on the need for monitoring Boca de la Barra to ensure hydric exchange with the Caribbean Sea (Rivillas-Ospina et al., 2020). In this sense, this research aims to contribute to the knowledge of the mouth dynamics for management strategies and decision-making by environmental authorities, in the face of the problems of one of the most productive ecosystems in the Caribbean region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

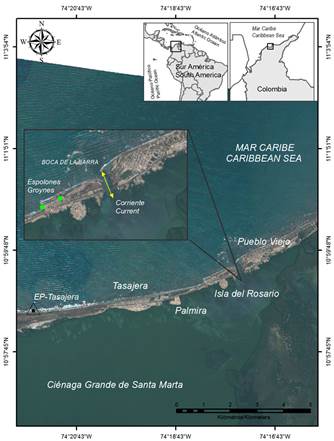

The analysis of the coastline’s evolution allows understanding the spatial-temporal variations resulting from the complex morphodynamics at the entrance of a barrier island and the adjacent coast. The area of Boca de la Barra was selected in this research in order to analyze the changes and evolution of the coastline in the 1953-2020 period. This mouth is located to the west of Salamanca Island, northern Colombia, in the coordinates 10°59’25.26” N and 74°17’26.51” W (Figure 1). It constitutes one of the main hydrological borders, and it is of vital relevance in the integral functions of the ecosystems of the CGSM ecoregion. In it, the west coast can be distinguished, which has been intervened with protection works for erosion control, as well as the east coast, which keeps its natural characteristics in the coastline, which is why they are separately treated for the sake of comparison.

Figure 1 General location of the study area. EP, Tasajera pluviometric station. Image: RapiDEye 2015. Source: LabSIS-Invemar.

A collection of satellite images from the sensors SPOT, RapiDEye, Sentinel 2, and Google Earth were used for the study, as well as aerial photographs at different scales, which selection was based on spatial resolution criteria between 5 and 20 m, a percentage of cloudiness lower than 15 %, and the date on which the sensor obtained the data. The latter, in accordance with its correspondence with different climatic seasons and contrasting years, given the presence of El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events, such as those that occurred in 2010-2011 (La Niña) and 2015-2016 (El Niño), which can cause periods of strong rainfall/drought. The images were rectified in the same coordinate system (Moore, 2000) to the reference of the World Geodesic System (WGS84) through 25 control points (GCP) acquired in the field with a Topcon GRS 1 (± 0.3 m) Differential Global Positioning System (DGPS), and they were projected using the Universal Transversal Mercator (zone UTM 18 North). Likewise, the coastlines were surveyed in the field with the DGPS, and then adjusted to the National Geodesic Network via post-processing. Based on the images, the coastline positions were interpreted and digitized following the criteria proposed by Ojeda et al. (2013), and the following procedures were applied: 1. Generation of seven geographical databases (GDB), 2. Calculation of the linear regression rate (LRR) and the Net Movement of the Shoreline (NMS). GDB generation was carried out with a GIS (ArcGIS 10.1), and the same coastlines were imported, which were previously grouped into the periods 1953-1997, 1997-2013, 2013-2020, and 1953-2020 for interannual analyses (annual coastlines); as well as into 2010-2016, 2016-2019, and 2010-2016 for intra-annual analyses (monthly coastlines within the same year).

The calculations of coast change values for each period were obtained using the extension Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS), which was developed by the United States Geological Service (USGS) (Thieler and Danforth, 1994; Thieler et al., 2005, 2009) and is widely applied in coast studies (Del Río et al., 2013; Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2015). The obtained data were compared between periods in order to understand the morphological dynamics of the study area, highlighting the results of previous studies and complementing the discussion with information about the Oscillation Index for the last 70 years and the Ideam data series (2010-2019) on the interannual rainfall variation, which were extracted from the Tasajera pluviometric station, to the north of CGSM, in the village with the same name.

RESULTS

Evolution and interannual trend of the coastline

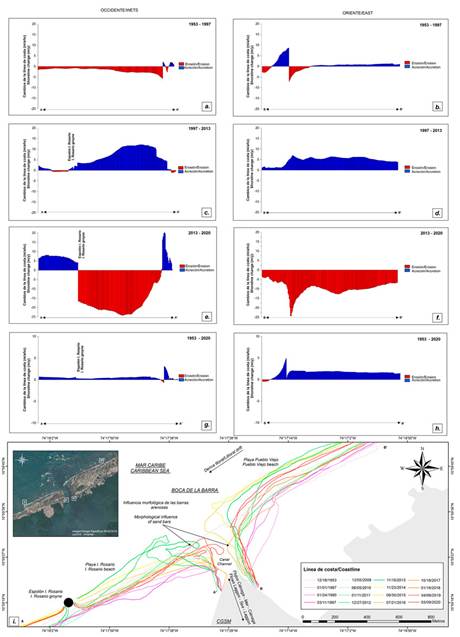

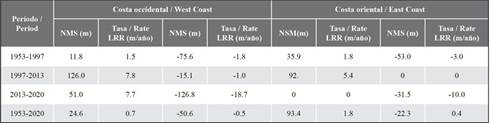

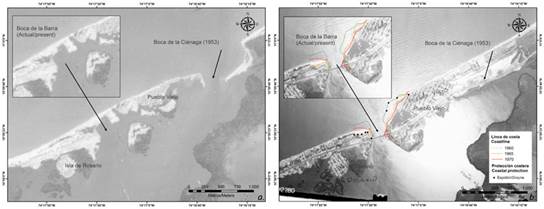

For the interannual analysis, the digitized series of the coastlines in the 1953-2020 period were used, and the calculation of the net changes (NMS) and the regression rates (LRR) originated by the configuration of the west (Rosario Island beach) and east (Pueblo Viejo beach) coasts in the marsh mouth were carried out. By studying the coastline for the 1953-1997 period, differences were observed in the distribution of erosion and accretion processes in the beaches adjacent to Boca de la Barra. However, due to the availability of aerial images and photographs, the calculated values of the coastline in the internal part of the mouth for this period were only obtained from 1987 onward. The west side experienced a trend towards coastal erosion, with an increasing pattern in the W-E direction, recording net changes of up to -207.5 m and erosion rates between -0.5 m/year and -5-7 m/year in the current mouth area. The least variations occurred in the west end of Isla del Rosario beach, with erosion rates lower than -2 m/year (Figure 2a). In contrast, in the east side of the mouth, the dynamics of the coastline were mostly dominated by the accretion processes in Pueblo Viejo beach, with maximum changes of 103.4 m and a rate of 8.7 m/year in the area next to the mouth. The internal part of the channel reached a net change and erosion rate of -256.8 m and -7.2 m/year, respectively (Figure 2b). It can be highlighted that, during this first period, the coastline was intervened with the construction of groynes in the 1950s and 1960s, which caused changes in the coast adjacent to the mouth.

In the 1997-2013 period, unlike the previous one, changes in the coastline were controlled by accretion in both sides of the marsh mouth. The incidence of the erosive process of previous decades led to new groyne-type protection works in order to safeguard the coast in Isla del Rosario beach, which were favored with sediment retention and influenced the morpho-dynamics of the beach and adjacent barriers. This new coast configuration generated annual changes in the west side, with gains that reached 233.9 m and a trend towards accretion between 1.9 m/year and 12.2 m/year (Figure 2c). In the same way, the east coastline evidenced processes of sediment supply on Pueblo Viejo beach, which favored changes of up to 185.6 m and a trend towards accretion, with rates between 2.2 m/year and 7.0 m/year and the lowest values inside the mouth, as well as indicating morphological stability (Figure 2d).

During the next period (2013-2020), the coastline behavior was dominated by an erosive trend in Islas del Rosario and Pueblo Viejo beaches, which changed the gain conditions shown in the previous period. Specifically, accretion processes on the west side were only significant in the area delimited by the groynes, at change rates of 8.1 m/year and the internal edge of the mouth, where they reached a value of up to 20.4 m/year, a trend that was associated with the sedimentation process at the beginning of the period, and later with the morphological dynamics of the barriers in the channel input from the Caribbean Sea. The coastline on Isla del Rosario beach exhibit changes that reached -170.6 m and a general trend of about -18.7 m/year, showing an erosion increase with respect to the previous period (Figure 2e). Likewise, the east side, which reported a trend towards accretion over the last 60 years, recorded changes in the coastline of up to -62.2 m and a maximum erosion rate of -24.5 m/year in the mouth edge (Figure 2f). For this period, the erosive trend in Boca de la Barra area was marked by an accelerated change in the coastline between 2015 and 2016, mainly on the east side.

According to the above, the changes in the Boca de la Barra coastline show a dynamic system in the interannual analysis, with a series of fluctuations in the dominating trends of erosion and accretion for different periods of time. These dynamics reflect conditions of stability on both sides of the mouth with respect to the coastline in 1953, expressed in accretion trends between 0.4 m/year and 3.1 m/year for the west coastline and 0.5 m/year and 2 m/year for the east coastline (Figure 2g). Likewise, there was a maximum accretion rate of up to 4.9 m/year in the mouth edge, where the hydric and sedimentologic exchanges between the lagoon and the Caribbean Sea are due to natural conditions (Figure 2h).

Table 1 Average values of the interannual evolution periods of the Boca de la Barra coastline, net changes (NMS), and linear regression rate (LRR).

Evolution and intra-annual trend of coastline in relation to enso events

The intra-annual study covering the most recent period (2010-2019) aims to understand the seasonal incidence and the presence of extreme events related to ENSO on the calculated values of the erosion and accretion trends. It is important to mention that this type of result can be approached in greater detail, depending on the available satellite images from different times for digitizing the coastline.

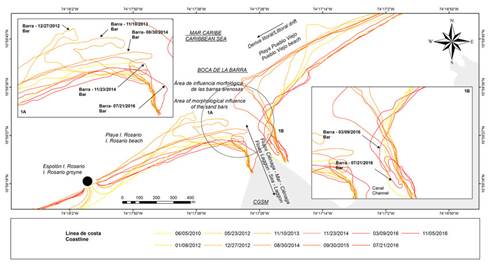

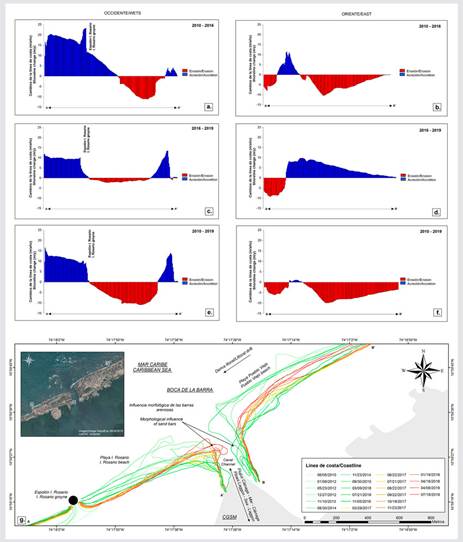

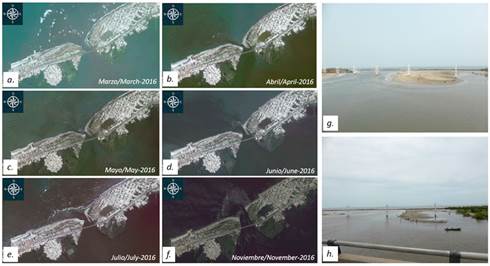

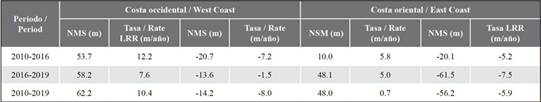

The 2010-2016 period was marked by the manifestation of La Niña and El Niño phenomena at their beginning and end, respectively. Under these conditions, the west side coastline experienced accretion trends in the sediment retention area, due to the effect of the groynes built after June 2010. The variation reached was 103.5 m, in addition to a maximum accretion rate of 23.3 m/year. The area adjacent to the groynes and with a higher exposure to coastal drift (adjacent to the mouth), even though it showed gains until November 2013 (Figure 3), yielded a final response of the coastline dominated by erosion, recording magnitudes of up to -34.2 m and rates between -1.0 m/year and -11.2 m/year (Figure 7a). Regarding the east-side coastline, the erosion processes were like those found on the west side, with an increasing W-E pattern in the coastal drift direction, which reached a value of -10.5 m/year in the area adjacent to the mouth. The accretion processes obeyed the growing dynamics of the coast, as observed in the digitized lines between January 2012 and September 2015 (Figure 3). Specifically, the internal area of the mouth had gains and losses of sediment deposits that determined differences in the domination of morphological processes, with erosion magnitudes of around -5.5 m/year and accretion levels between 1.4 m/year and 11.5 m/year (Figure 7b). During this period of analysis, a temporary closure of the channel opening between March and July 2016 was observed, with a reduction of 140 m in the current width (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Intra-annual morphological changes in Boca de la Barra between March 2016 and November 2016 (Source: Images Google Earth). a-f. Mouth temporary closure and opening. g. Prolongation of the barrier inside the channel (east) and reduction of the mouth width, March 2016. h. Loss of barrier and mouth width, July 2016.

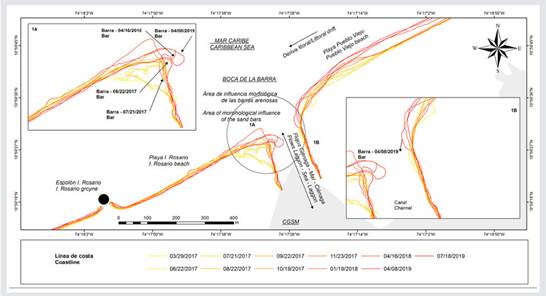

Between 2016 and 2019, when there were no strong ENSO events (Figure 5), the monthly coastal variations showed a change of trend in the morphological dynamics of Boca de la Barra, decelerating the erosion process at some sites and recovering other eroded ones. On the west side, the beach adjacent to the groynes showed an erosion reduction reaching up to -2.3 m/year, while the area between groynes remained stable, and accretion rates decreased down to 10.0 m/year with respect to the previous period (> 15.0 m/year). The highest values were recorded in the area of morphological influence of the barriers in the mouth, with changes of up to 91.5 m and accretion rates of 13.5 m/year (Figure 7c). The formation of barriers was identified in the digitized coastlines of July 2017, January 2018, April 2018-2019, August 2018, and July 2019, evidencing sediment transport from the system into the channel (Figure 6). The east coastline was mainly controlled by accretion, with gains of up to 69.0 m and rates that reached 9.8 m/year. Erosion processes took place in the mouth area, with net changes of up to 18.6 m and a maximum rate of 9.2 m/year (Figure 7d).

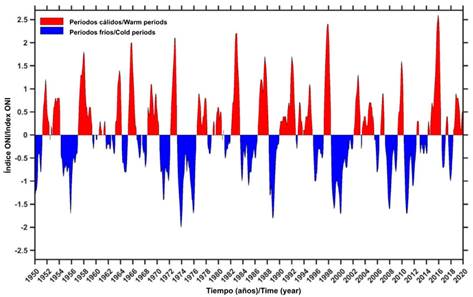

Figure 5 Time series of the Southern Oscillation Index for the last 70 years. Data source: NOAA (2022).

Finally, the results obtained for the whole 2010-2019 period show that, in the last decade, the morphological dynamics of Boca de la Barra have been controlled by a coastal erosion trend with rates between -0.8 m/year and -11 m/year, except for the groynes’ sediment retention area. Particularly, the mouth area (channel) has important morphological dynamics, where the west and the east accretion (13.9 m/year) and erosion (-6.0 m/year) trends can be distinguished from each other (Figure 7e-f). The shift of monthly lines during the period reflects the effect of extreme drought events associated with El Niño phenomenon on coastal processes.

Table 2 Average values for the intra-annual evolution period of the Boca de la Barra coastline, net changes (NMS), linear regression rate (LRR).

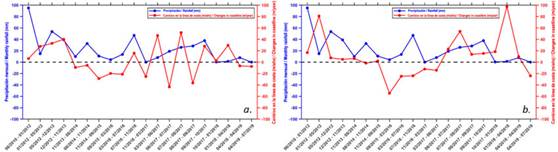

To visualize the above, a comparison was carried out between the changes in the coastline and the interannual variation of the recorded rainfall in the Tasajera pluviometric station, which showed a morphological response to periods of higher and lower rainfall in the Boca de la Barra area between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 8).

DISCUSSION

To understand the morphological dynamics of this mouth, it is important to review a series of anthropogenic interventions that occurred to the northeast of the CGSM between the 1950s and 1970s. During this period, the recent major changes in the coastal morphology occurred between the sector of the town of Ciénaga and Rosario Island, due to the construction of the Ciénaga-Barranquilla road. Under natural conditions, water exchange flowed from and to the CGSM through the marsh mouth, which covered 800 m between the limits of Ciénaga and Pueblo Viejo (Erffa, 1973), favoring the communication between water flows as well as morpho-sedimentary processes that are typical of the mouth and the sea (Warrick, 2020).

According to the 1953 Igac photograph, the current location of Boca de la Barra between Pueblo Viejo and Rosario Island was the prolongation of Salamanca Island, which was constituted by beach deposits. Moreover, due to its morphological features, it would correspond to a paleochannel originated during the evolution process of the coastal barrier (Wiedemann, 1973). The geo-morphological changes of the system, given the placing of barriers (dyke) in the hydric exchange between the marsh and the sea, influenced an accelerated erosion process between the 1950s and 1960s, forced by marine currents (Erffa, 1973). This led, between the 1960s and 1970s, to the building of groynes in beaches, aiming to control erosion and maintain the permanent communication between the water body and the Caribbean Sea (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Morphological changes in the connection area between CGSM and the Caribbean Sea. a. Location of the mouth in 1953 and today, photographs by Igac 1953. b. Approximated coastlines in 1960, 1965, and 1970, as digitized by von Erffa (1973). Photographs Igac 1987.

This new configuration of the CGSM-Caribbean Sea connection and the anthropogenic interventions at the time was decisive in later morphological processes. In the interannual results obtained from 1953 to 2020, it is observed that the spatial-temporal evolution of the coastline has responded to the control exerted by the erosion and accretion processes in the mouth area, which are related to the general behavior of the coastal dynamics of Salamanca Island (Gómez et al., 2017). The above has determined the incidence cycles of these processes (erosion/accretion) on the coast, as well as the dominance of trends in different periods of time, which, when compared to local and regional climatic conditions, be it under normal or medium conditions (dry for El Niño and wet for La Niña), would reflect a higher or lower forcing, which may be decisive in coastline variations and the morphological configuration of the mouth.

The periods 1953-1997 and 2013-2020 showed a coastal erosion trend; in the first case, a correspondence can be observed between the morphological dynamics of the whole period and that experienced in the first decades after the natural mouth’s change of position. Furthermore, in both cases, a correspondence is observed with the years of rainfall deficit and severe drought caused by strong El Niño events over the last 67 years (Figure 5). For example, these events took place in 1972-73, 1982-83, 1997-98, and 2015-16, with effects on the Caribbean region (Montealegre, 2014; NOAA, 2016). In these scenarios, coastal erosion was forced by the decrease in sediment input, swell intensification, and coastal transport along the Salamanca Island (Invemar, 2014a; Gómez et al., 2017).

On the contrary, in the intermediate period (1997-2013), when a change in the erosive cycle and the coastline response to accretion trends occurred, a concordance with strong La Niña years was evident. For instance, in the 1999-00, 2007-08, and 2010-11 events, when there was a rainfall surplus (Montealegre, 2014). These events also have an effect on the hydrologic regime of the CGSM’s environment, favoring the availability of sediment inputs in the system as well as the exchange through Boca de la Barra (Blanco et al., 2006; Restrepo et al., 2015; Invemar, 2017). These conditions generate sediment accumulation in the adjacent beaches and a deposition front towards the continental platform (Invemar, 2015b).

On the other hand, the results of the intra-annual evolution and the trends of the last decade (2010-2019) evidence that changes in the coastline are also modulated by climate seasonality, given its influence on factors such as rainfall, river discharges, winds, waves, among others, which intervene in the hydro-sedimentologic dynamics of Boca de la Barra (Invemar-Corpamag, 2018). During the dry and higher-intensity trade winds and wave season (Invemar, 2015a, 2017; Restrepo et al., 2015), and, due to the effect exerted by the tides, a greater process of coastal transport was generated in the mouth area, which can be observed in the morphological changes in the channel opening and the barrier position, becoming narrower along the coast and showing morpho-dynamic processes within the mouth.

These processes that influence morphological dynamics are forced by salty water inflows into the CGSM, due to low freshwater levels during low rainfall and a minimum input of it into the system from tributaries such as the Magdalena, Fundación, Aracataca, and Sevilla Rivers (Invemar-Minambiente, 2018). When these environmental conditions remain constant over time, they favor erosive trends in the coastal area, but cause sedimentation within the channel, such as that identified in the 2010-2016 period, on which the months of strong drought by the end of 2014 and mid-2016 had a significant impact (NOAA, 2016).

A wet time with weak winds and high rainfall (Invemar, 2015a, 2017; Restrepo et al., 2015) favors the increase in water levels inside the marsh and in the flows from the CGSM to the sea, which causes the transport of sediments deposited in the mouth during the dry season, redistributing them towards the Rosario Island and Pueblo Viejo beach areas and the sedimentation front of the continental shelf (Invemar, 2015b). Normally, these dynamics reduce the barrier length and width, increase the mouth breadth, and recover the water flows to the sea (Invemar-Minambiente. 2018). In this case, when rainfall periods and sediment supply to the coast are dominant, accretion processes occur, such as those evidenced in the analysis of the seasonal coastline in 2016-2019.

CONCLUSIONS

The morphological behavior of the lagoon mouth defines a dynamic system that, in the long term, has showed changes and temporal trends associated with the dominance of erosion and/or accretion processes. The tendency or the interannual response of the coastline, as intra-annually analyzed in the mouth, changes according to the effect caused by the manifestation of ENSO events (El Niño/La Niña), which have significantly influenced the coast changes and have determined a cyclic behavior of the coastal processes acting on the mouth for decades, such as those that occurred in the periods 1997-2013 and 2013-2020, in which strong events took place. Although, historically, the Boca de la Ciénaga had changes in the coastline which were related to anthropogenic factors, over the last 67 years, its morphological dynamics have shown a trend towards seeking the system’s equilibrium conditions with respect to the coast characteristics in 1953. However, it is possible to identify that these dynamics (equilibrium) are lower towards the west coastline, which was intervened with hard works; and greater in the less intervened east coastline.

The analysis of the intra-annual evolution and trends shows that the morphological response of the mouth is modulated by climate seasonality. The periods with strong ENSO events determine the erosion/accretion trends in the long term, as well as the water flows from and to CGSM. The dominance erosion processes in the last decade indicates a sediment input deficit, which conditions the morphological balance between both coasts of the mouth (west-east). Moreover, current groynes are affecting the changes in the coastline, the adjacent beach, and the morphological dynamics of the barriers towards the mouth.

text in

text in