INTRODUCTION

Morphodynamics provide a better understanding of the relationship between coastal processes and morphological responses in littoral areas (Wright and Thom, 1977). This interaction applies to beaches (Wright et al., 1979) and was introduced by authors such as Sonu (1973) and Sonu et al. (1973). Short (2020) defines the beach type as the shape of a beach according to the relative contribution of the waves and the tides, while the beach state refers to the morphodynamic range of each type. In addition to the spatial-temporal domain, the core of morphodynamics is the constant interaction between two parameter groups: on the one hand, sediments, and geology; and on the other hand, waves, winds, and currents (Jackson and Short, 2020).

Beaches are modulated by the waves. This (with the tide) allows them to be organized within a sequence of morphodynamic states and types (Jackson and Short, 2020), which have been proposed by Wright and Short (1984), Masselink and Short (1993) and Short (1999). Thereupon, beach morphodynamics in natural environments can be classified as continuously dominated (predominant) by the waves or as modified and dominated by the tide (Gómez-Pujol and Orfila, 2020; Short, 2020). Other studies (Short, 1999; Masselink et al., 2006; Reichmüth and Anthony, 2007, 2008; Price et al., 2014) state that the tides, the wave energy level, and beach morphology determine the type, intensity, and duration of the processes at work in the transversal profile of a beach. These processes shape the beach but depend on the balance of sediments, which are contributed through different sources determined by the beach inputs and outputs (littoral cells) (USACE, 1984) and related to accretion and coastal erosion (Komar, 1983). In tidal or tide-dominated (TD) systems wave energy is very low, and the oscillation of the tides and the tide currents becomes important. This causes the classification to vary from a high energy dominated by waves to a lower energy dominated by the tide (Short, 2020).

The most important beach classifications around the world have been carried out in Australia (Wright et al., 1979; Wright and Short, 1984; Masselink and Short, 1993; Masselink and Pattiaratchi, 2001; Masselink et al., 2006; Sénéchal et al., 2009; Valiente et al., 2019), and the United Kingdom (Scott et al., 2011; Valiente et al., 2019). Classifications have also been carried out in Brazil (Pereira et al., 2010; Andreoli et al., 2019; Holanda et al., 2020), Malaysia (Mustapa et al., 2015), Mexico (where comparative analyses between subaerial and sub-tidal sections were carried out) (Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu et al., 2013, 2016, 2017; Torres-Freyermuth et al., 2017; Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu and Vidal-Ruiz, 2018), and France (Sénéchal et al., 2009; Castelle et al., 2014; Senechal and Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu, 2020).

In Colombia, few works have classified beach morphodynamic states. Agámez (2013) classified some beaches in the Caribbean. In the Pacific region, works have been carried out in rocky mesotidal beaches, such as the one by Gómez-García et al. (2014). On the other hand, studies have been conducted in the region, albeit related to delta morphodynamics (Restrepo et al., 2002; Restrepo and López, 2008). Other authors have characterized the morphodynamics of Colombian beaches because of climatic conditions, that is, dry epoch profiles (winter profiles in middle latitudes) or wet epoch profiles (summer profiles in middle latitudes), only dominated by the waves, but omitting the environmental conditions of each region (Correa and Restrepo, 2002; Agámez, 2013). Considering that there are many environmental differences between the Colombian Caribbean and Pacific regions and their corresponding beaches (Ricaurte-Villota et al., 2018; Coca and Ricaurte-Villota, 2019), a classification for the Colombian coasts cannot be generalized.

The objective of this research is to carry out a morphodynamic classification for La Bocana beach in the Colombian Pacific and determine the natural causes affecting beach morphology at intra- and interannual scales. The morphodynamic classification on a beach in the Colombian tropical Pacific is presented, which is dominated by a microtidal system. Moreover, the variables influencing the classification are defined on different spatial and temporal scales. From basic and applied science points of view, and from a perspective of coastal management, it is important to carry out beach morphodynamic studies, as the way in which tropical beaches respond to environmental processes such as sand supply (modulated by precipitation via river discharge) and wave forcing, which hinders the rational development of coastal areas in Colombia.Understanding the functioning, period, duration and causes of sediment migration is essential from a perspective of interventions (mitigation works) in beaches with a coastal erosion background (Karunarathna et al., 2012; Castelle et al., 2014; Senechal and Ruiz de Alegría-Arzaburu, 2020).

STUDY AREA

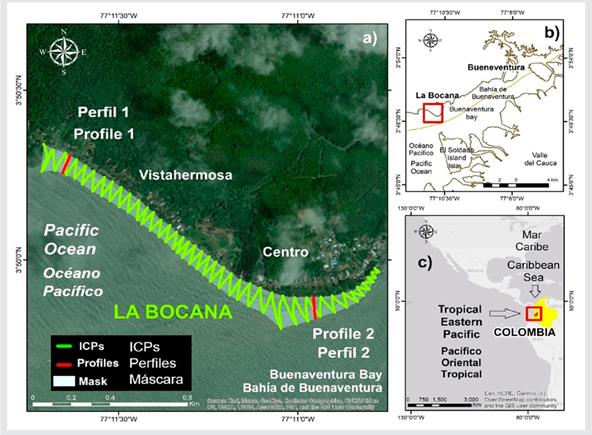

La Bocana beach (2.13 km long) is located north of the Buenaventura Bay mouth in the Colombian Pacific coast, which is part of the eastern tropical Pacific (Figure 1). The beach precedes active cliffs with 2 - 6° slopes and is composed of medium-fine grain lithic sands with abundant ferromagnesian mineral contents, which is why it acquires dark colors, with the occasional presence of bioclasts. The region is characterized by an annual average precipitation of 7,609 mm·year−1 (Ricaurte-Villota et al., 2018), among the highest in the world. The tides are mixed semidiurnal, with an average macrotidal amplitude (Vásquez-López et al., 2020) of approximately 4.5 m in spring tides (Correa and Morton, 2010). The waves reach approximately 0.5-1.5 m (Martínez-Ardila et al., 2005), but they can reach heights between 2.5 and 3.5 m during strong wind periods (Correa and Morton, 2010). Thomas et al. (2014) mentions a significant wave height (Hs) between 0.88 and 1.02 m, with a minimum Hs 0.71 and a maximum value of 1.21 m. The lowest wave height occurs in April, while the highest value is observed in October (Ricaurte-Villota et al., 2018). The average wind speed is 2.3 to 3.7 m·s−1, with a predominantly northeastern direction (Thomas et al., 2014). The geomorphology of the Pacific is dominated by low coasts (71 %) classified as deltas (San Juan), barrier islands, muddy coasts, lagoon mouths, continental beaches, and estuaries (Posada et al., 2009).

The beaches in the study area generally have variable amplitude (between 2 m during high tides and approximately 600 m during low tides) and a well-defined berm at the vegetation line, with a great accumulation of plant material and wastes. The berm is up to 5 m high, and, in some parts, it has little crests that mark the advancement of the latest highest tide (Posada et al., 2009). Wave-formed sedimentary structures are common in the medium-tide strip, whereas bioturbation traces are more frequent in the areas exposed during low tides. Runoff structures are also observed (Posada et al., 2009). The tide range in the area derives from the presence of an extensive low-tide delta at the southern end of the bay mouth (El Soldado island), which evinces the predominance in the coastal drift of strong low-tide currents. This ebb delta is not seen in front of La Bocana beach.

Figure 1 Location map of the study area. a) La Bocana beach, two sectors marked: Vistahermosa and Centro. Green transects correspond to zigzag paths followed to generate independent control points (ICPs) by means of walking with a DGPS at the beach, to mark the interpolation zone and generate the DEM. Red lines correspond to the two beach profiles extracted (1 and 2). b) Buenaventura bay. c) Location of Colombia in the eastern tropical Pacific.

METHDOS

Topographic data (DEM and beach profiles)

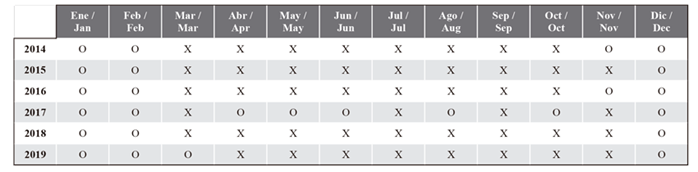

The topographic data on the independent control points (ICPs) were obtained between February and November for six years (2014-2019) (Table 1) in the area exposed during the lowest tides or at the beach of the emerged area. The data were obtained via a differential global positioning system (DGPS) with GNSS (GPS and GLONASS) and post-processing geoidal correction (Fontán et al., 2009) using the Topcon Tools software ant the MAGNA ECO network Buenaventura station located 15 km away from the study area. The ICPs (X, Y, Z) were obtained using the equipment at the points and in the Autocollect mode (1 data per second), as well as referenced in WGS 84, zone 17. The elevations at the sites were the average height of the low tide (MLT) (+ 12 m in ellipsoidal heights, Buenaventura Point). The data were taken during the spring tide (or pujas, a local name) of each month to ensure that a larger beach area was covered by the sampling process, from the edge of the water to the edge of the back beach. The duration of each sampling was 4 h (2 h before and 2 h after the moment with the lowest tide), and the zigzag method was employed (Fontán et al., 2009). The beach profiles were taken with the same reference point (for Centro: 3° 49.894’N-77° 10.954’O; for Vistahermosa: 3° 50.334’N-77° 11.638’O), following the same direction and using a compass (for Centro: 175°; for Vistahermosa: 220°) from the reference point. For the sedimentological analysis, three samples of the two beach profiles were taken (infra-, supra-, and mesotidal areas) (Figure 1).

The data were exported in shapefile format using the ArcGIS software. The first filter consisted of eliminating the points with a vertical precision higher than 0.75 cm. The second filter was calculated using the root mean square error (RMSE), which verified the precision of the ICPs with regard to the Z value. Afterwards, the points were interpolated using their Z values through the Kriging method (Fontán et al., 2009). The beach profiles were taken via DGPS in the Vistahermosa (Profile 1) and Centro (Profile 2) sectors, taking the orthometric correction data (Figure 1). The DEM allowed identifying the dominant characteristic morphology. The characteristics observed in the 3D DEMs (1:2,000 scale) allowed generating the predominant plan view model adapted from Wright and Short (1984). On the other hand, the conceptual beach models of Masselink and Short (1993) were adapted, aiming to identify and propose models according to that observed in La Bocana beach. These models were denoted as beach types.

Beach state data (morphodynamics)

In performing morphodynamic classification, the beach slope, the tidal range, the wave height, and the sediment grain size are considered. The slope was extracted from peach profiles 1 and 2 for each sampling. To obtain the sediments’ granulometric data, the samples were sieved with a seven-mesh vibrating sifter, with differences of 1 ɸ (Phi) and the following openings: 2 mm, 1 mm, 500 μm, 250 μm, 125 μm, 63 μm, and the base measurement (Blott and Pye, 2001). To describe the tide, data for the 2014-2019 period were employed. These data were taken from a virtual buoy located in Buenaventura Bay (3° 54.00’ N, 77° 6.00’ W), which extracted information every four hours based on the Windows tide and current prediction program (http://www.wxtide32.com/). The wave description was carried out using data from a virtual buoy in front of the port of Buenaventura (3.61° N, 77.61° W) for the 2014 - 2019 period. This buoy corresponds to the fifth-generation Era-5 reanalysis provided by the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), with a spatial resolution of 0.12° and a temporal resolution of six hours (Hersbach et al., 2019). The average and extreme deepwater wave regimes (ECMWF) were propagated towards the coastal edge of La Bocana, by means of the SWAN (Simulating Waves Nearshore) numerical spectral wave propagation model (Booij et al., 1999). This numerical model incorporates all of the fundamental processes associated with wave propagation (refraction, diffraction, shoaling, and breaking).

Expected beach state

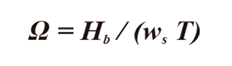

The morphodynamic state analysis was carried out using the data and the classifications proposed by Wright and Short (1984) and Masselink and Short (1993). These classifications employ a method comprising a mathematical equation that predicts the morphodynamic state of a beach by means of the grain fall dimensionless parameter. The classification considers the beach slope, the tidal range, the wave height, and the sediment grain size. The equations for Wright and Short’s morphodynamic state parameters (1984) posit that beach states are related with the characteristics of the waves and sediments via the dimensionless fall velocity (equation proposed by Ferguson and Church, 2004):

Where Hb is the wave height at breaking, ws is the grain fall velocity, and T is the mean wave period. According to Wright and Short (1984), Ω < 1 denotes a reflective beach, Ω ~ 6 denotes a dissipative beach, and the intermediate states are denoted by 1 < Ω < 6.

In the same way, this work employed Masselink and Short’s (1993) relative tidal range (RTR) model for macrotidal beaches (> 3 m), which expresses the relationship between the tidal range and the breaking height. High (> 3 m) and low (< 3 m) RTR values indicate the dominance of waves and tides, respectively.

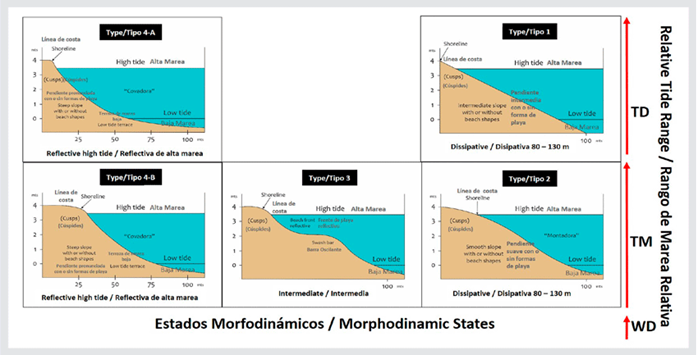

Where TR is the tidal range and Hb is the wave height at breaking. Finally, the conceptual model proposed by Masselink and Short (1993) was employed. This model is called Beach Model, and it can predict beach morphology (beach type) using the two equations, thus obtaining a morphodynamic classification based on the dimensionless fall velocity (Ω) and the RTR. The model classifies morphodynamic states as reflective, intermediate, and dissipative, as a function of modifiers or dominant agents according to the spring tide amplitudes (Mean Spring Tide Range, MSR). Scenarios may involve dominant waves (WD), modified tides (TM), and dominant tides (TD) for low, intermediate, and high ranges, respectively.

RESULTS

Observed beach types and states

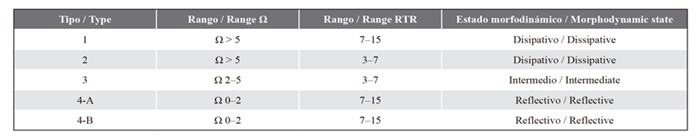

Based on the definition and classification of the beach types and states, the beach profiles were taken, measured, and grouped according to their predominant shape and slope. Afterwards, the results obtained regarding the beach state and type of each profile were adapted to the profiles proposed by Masselink and Short (1993) and Wright and Short (1984), generating and proposing four beach types and an additional one with a slight modification (Table 2 and Figure 2). Type 4 showed a special variation and was classified as 4-A and 4-B. The difference is because the berm was occasionally seen at the edge of the back beach, whereas, at other times, it is located 20 m away from the same beach in a seaward direction.

Table 2 Results obtained for the Ω, RTR, and morphodynamic state parameters according to the classification proposed by Masselink and Short (1993).

Figure 2 Beach types proposed based on the predominant beach states in La Bocana beach. They are related to the RTR (Relative Tide Range) proposed by Masselink and Short (1993).

Figure 2 shows that the type-1 beach profile is simple and exhibits a single slope towards the ocean. The beach shows a gentle slope and cusps towards the back part of the beach. Other beach formations are soft or absent. This beach type was classified as having dissipative beach morphodynamics. The type-2 profile tends to accumulate sediments and shows a wide berm towards the bottom of the beach (with no cliffs or embankments). This profile is called “Montador” by the local community, as it accumulates a large amount of sediments, increasing the elevation of the beach. Type 2 shows an intermediate-position coastline that is generated by the berm and is not associated with coastal erosion or coastline retreat processes. Finally, the beach may contain formations or be flat, and it is classified into a dissipative morphodynamic state.

The type-3 profile shows a berm with accumulated sediments towards the bottom of the beach. The berm is shorter than that of type 2, as the sediments are redistributed along the profile, generating a new berm (oscillating bar) in a lower area. A reflective beach front is generated between the two berms and the end of the beach profile, which is classified into an intermediate morphodynamic state. Finally, the only difference between types 4-A and 4-B is the position of the berm, which is sometimes located towards the back beach (4-A) and sometimes towards the middle of the profile (4-B). Type 4-A is prone to coastal erosion. The two types of profile are characterized by having the most pronounced slopes among the types. The beaches may or may not contain formation. There may be low-tide terraces at the base or at the end of the profile. Type-4 beaches are classified as exhibiting high-tide reflective morphodynamics. This beach type is called “Covador” by the locals.

Four beach profile types were obtained for the area (Table 2 and Figure 2). Type 4 showed a spatial variation and was classified as 4-A or 4-B. The difference is because the berm is sometimes located at the edge of the back beach, and it sometimes is approximately 20 m away from it in a seaward direction.

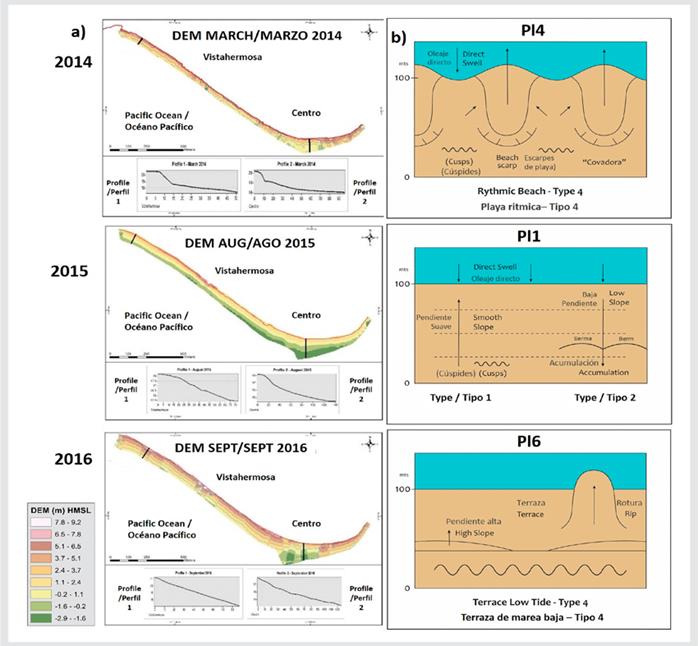

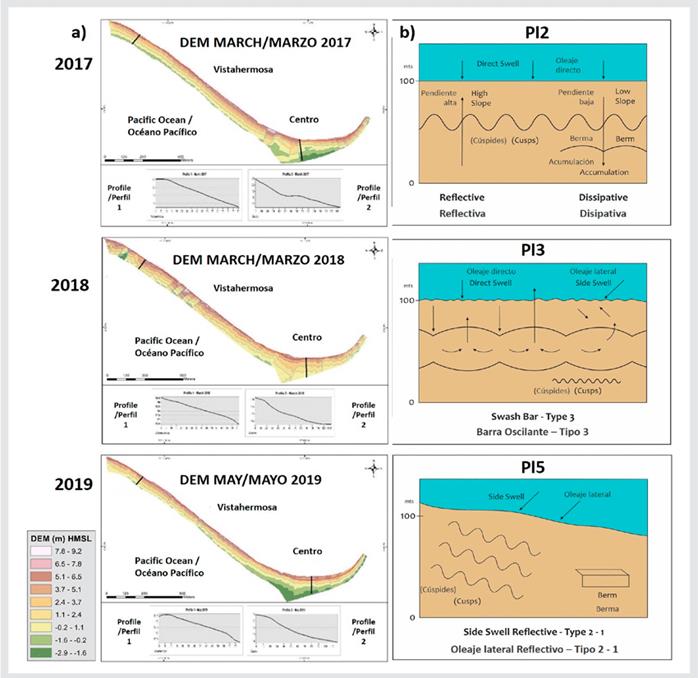

Six plan models were obtained for the beach, which are related to the beach type (Figure 3b). In the same way, the models are the result of the average of the campaigns and of the observation of the DEMs obtained (Figure 3a). Each model represents the morphological differences within a year, as a result of different coastal processes (weather, tide, waves, currents). The plan view models are related with the relief shapes observed in the DEM (Figure 3a) and are classified as Pl1, Pl2, Pl3, Pl4, Pl5, and Pl6 (Figure 3b), which is described below.

The Pl1 plan view model is an upper plan graphic representation corresponding to the type 1 and 2 profiles. In Pl2, a combination or intercalation between the reflective (high slope) and dissipative (low slope) morphodynamic states is observed, with the presence of beach formations, (e.g., cusps). The process observed in the Pl3 model is related to a type-3 profile with an oscillating bar, in which the waves, in a perpendicular or oblique direction (two scenarios) generate long wave shapes (wide cusps) in the intermediate zone of the beach. The presence of short-wave cusps (small width) is not discarded.

Figure 3 a) Examples of the beach DEMs and the extracted profiles (1 and 2) are shown for a representative month of each year (2014-2019), with average heights in meters above the sea level. b) Plan view model related with the DEM and the profile type.

Figure 3 (Continuation). a) Examples of the beach DEMs and the extracted profiles (1 and 2) are shown for a representative month of each year (2014-2019), with average heights in meters above the sea level. b) Plan view model related with the DEM and the profile type.

The Pl4 model shows a rhythmic beach with broad undulations or cusps that move from the low-water line to the coastline. Long-wave escarpments with pronounced cusps are generated (which may also accompany short-wave cusps), typical of a type-4 beach profile. The Pl5 plan model is characterized by lateral waves that generate an inclined beach and may have cusps with berms. These formations may also be present in type 1 and 2 profiles. Finally, the Pl6 plan model has the highest slope, a low-water terrace, and sequences of small bays and horns created by rip currents that may accompany the terrace. The upper beach may have short-wave cusps typical of type-4 profiles. The beach morphology observed and proposed based on the DEM is seem along the beach, and it may show sectoral variations. For example, the Centro area may have a Pl3, and there may be a Pl6 at the same time in another area of Vistahermosa.

Beach state data (morphodynamics)

Coastal dynamics are associated with the flow and reflow of the tide (water entry and exit) and their relationship with local intertidal flats. The beach has a sediment composition that is continental in origin, with quartz and heavy minerals, as well as a shallow agitated marine depositional environment. No variations were detected for the years in which the sampling campaigns were carried out. Fine sand (100 %) was observed in all campaigns, which suggests a low-energy regime that has been consistent over the years. The average fine grain size of the selection varied from moderately good to good in all sampling campaigns. The symmetry coefficient values vary from thin to thick with the asymmetries. The bell shape of the data distribution between % weight and ɸ is generally mesokurtic, but it varies from platykurtic to leptokurtic. The beach slope varies from 1 to 4°.

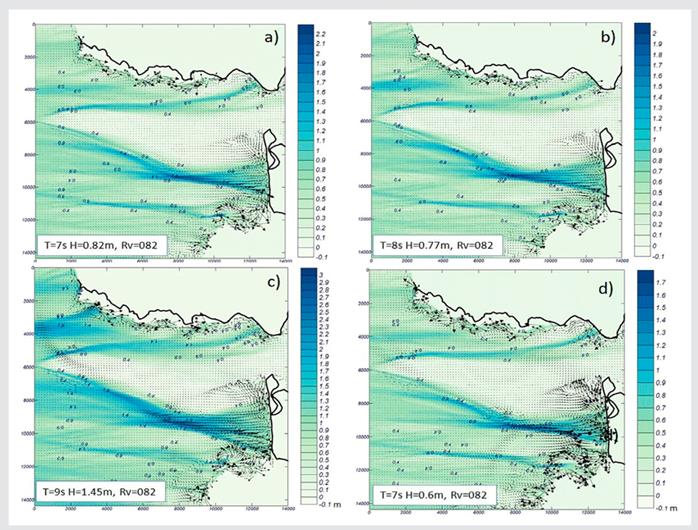

The behavior of the wave fronts represented by the SWAN satisfies the initial sea state conditions provided (especially Hs), reaching wave heights that do not exceed 2.0 m in average conditions and that, in a wave height scenario with a minimal probability of exceeding, would not go over 2.5 m. This agrees with what was found by Otero (2004). Therefore, the coastal area of the Buenaventura Bay mouth may be regarded as a low-energy one, where the most energetic waves (the highest ones) are not located in La Bocana beach; they are in front of Soldado island. The maximum height is observed towards the Vistahermosa sector, reaching an Hb of 0.9 m (Figure 4).

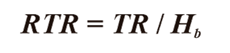

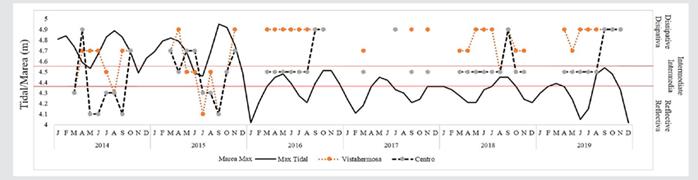

Figure 5 shows that the tidal range during the spring tide has two maximum values throughout each year: one around February or March, and another one between September and October. Moreover, the greatest tidal ranges are observed between 2014 and early 2016, followed by the maxima of 2019, although the latter had a lower magnitude. As for the maximum wave height, (Hmax) for the day with the highest tide and its period, the values reported throughout this study oscillate between 0.55 and 1.4 m and between 4 and 14 s, respectively. The wave parameters do not show a tendency during the analyzed time, even though, between 2016 and 2018, the greatest Hmax heights were observed. Similarly, during these years, there is a high variability in the values for both Hmax and the period, whereas, in 2014 and in the second semester of 2015, Hmax shows a lower data variability, remaining over 0.7 m and with periods between 5 and 9 s, that is, intermediate wave heights, and a more recurrent wave train, which agrees with the observed reflective morphodynamic states.

Figure 4 Model output showing the current vectors, and, in the palette, the wave heights obtained (m). The waves were simulated with the periods typical of the zone with 7 a), 8 b), and 9 c) sec. d) average wave scenario.

Expected beach state

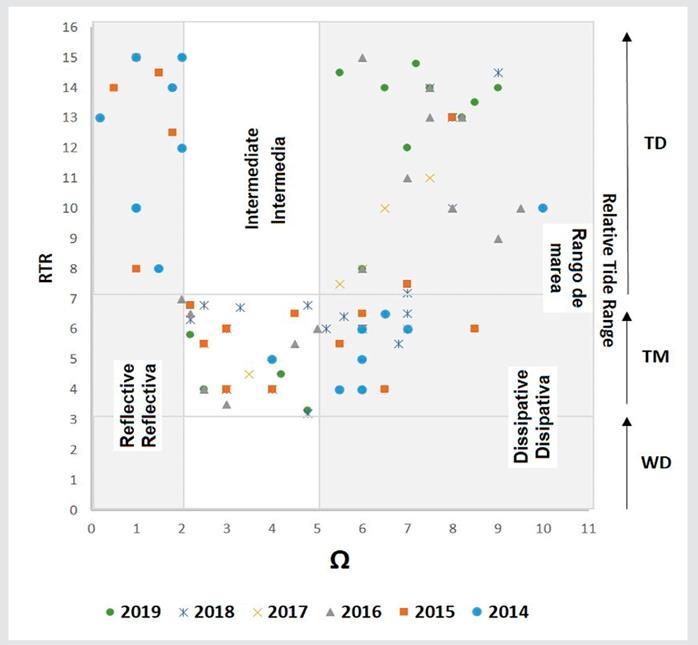

The results showed a predominance of the intermediate and dissipative states, represented by most of the data, as well as the presence of some data corresponding to reflective states for 2014 and 2015. The tides in the TM and TD ranges were the dominant agent, recorded by the number of data in each field (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Results distribution for the Ω (beach state) and RTR (beach type) and the morphodynamic state and type, respectively, according to the classification proposed by Masselink and Short (1993). Beach type: WD, TD, and TD (Masselink and Short, 1993; Short, 2020; Wright and Short, 1984). Beach state: reflective, intermediate, and dissipative. Each point (geometric shape) represents the value obtained in each measurement with regard to Ω and RTR (beach state and type). Colors correspond to the different years in the time series.

Relationship between the beach type and the morphodynamic state (beach state)

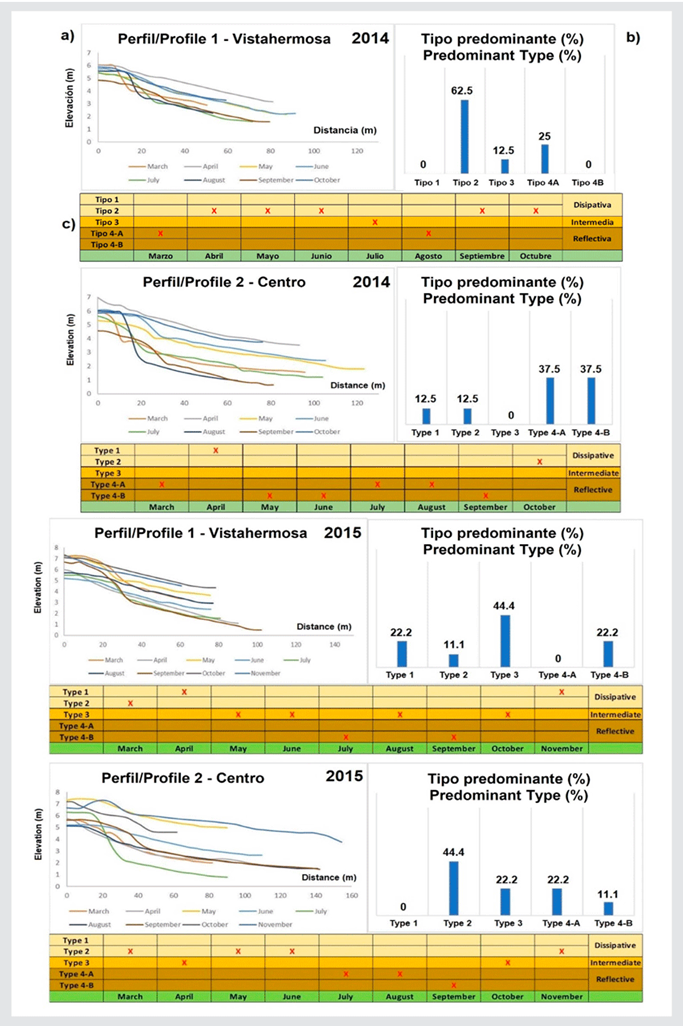

The analysis regarding the predominant beach profile showed a varied temporal distribution. Type 2 was dominant in 2014 at Vistahermosa beach (profile 1, Figure 1, “Montador”) (62.5 %), with a dissipative morphodynamic classification. The type-4-A profiles (25 %), classified as reflective with a tendency towards coastal erosion or coastline retreat, were observed in March and August. The beach profile of the Centro sector (profile 2, Figure 1) showed a predominance of types 4A and 4B, which indicates a tendency towards sediment loss or coastal erosion and a reflective morphodynamic state (Figure 7). In 2015, the Vistahermosa beach profile was dominated by type 3 (intermediate morphodynamics, 44.4 %), type 1, and type 4B. In the same year, the Centro sector was dominated by type 2 (dissipative morphodynamics, 44.4 %) (Figure 7).

Figure 7 a) Monthly beach profiles (Vistahermosa and Centro) for 2014 and 2015. b) Predominant beach profile type in % for each year, sector, and profile. c) Beach profile type for each month and its corresponding morphodynamic state, marked with a red x.

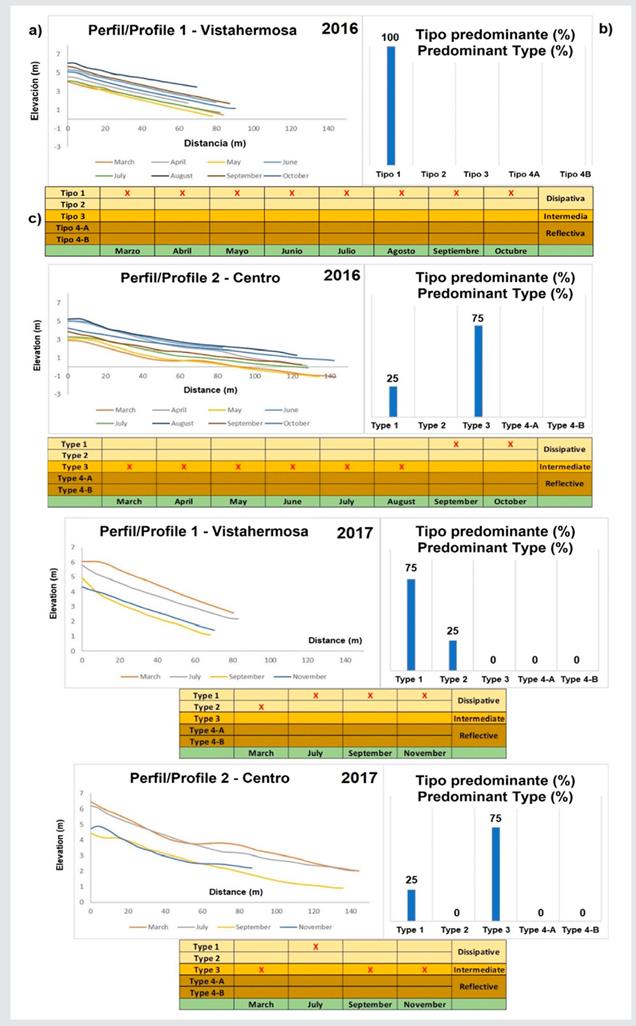

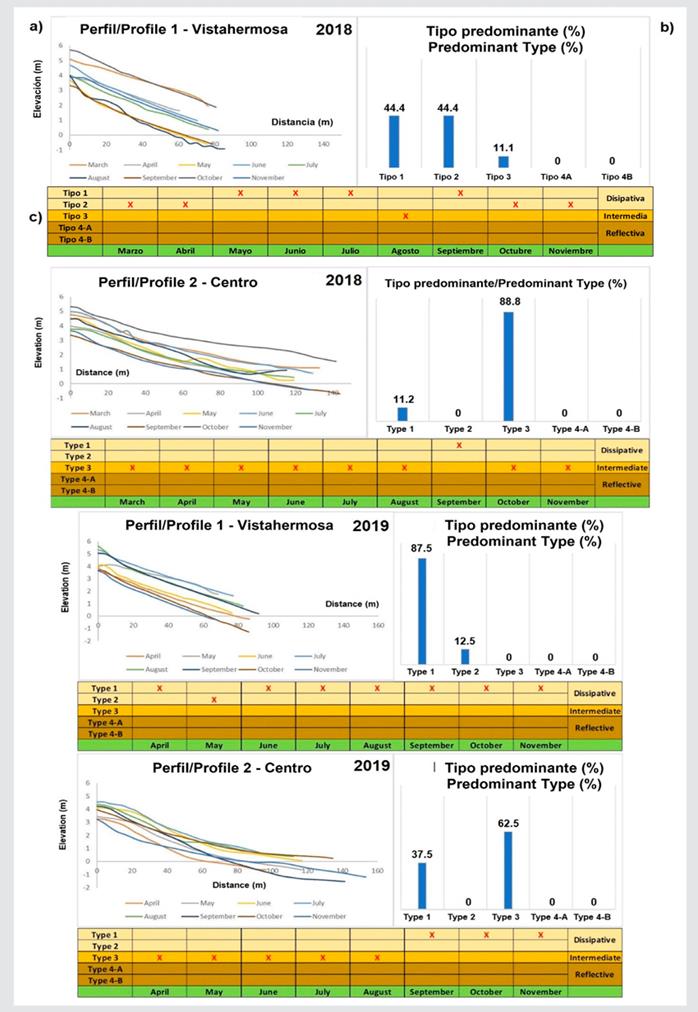

Type 1 (dissipative) was dominant (100 %) in 2016, 2017, and 2019 in the Vistahermosa sector. In the Centro sector, there was a predominance of type-3 intermediate morphodynamics until August, and type 1 predominated in September and October (Figures 8 and 9). In 2018, types 1, 2, and 3 were dominant in the Vistahermosa sector; the Centro sector was dominated by type 3.

The plan models revealed variable conditions in different parts of the beach and contain combination of profile types. This is caused by different climatic and hydrodynamic conditions, by the position of other sediment planes, and by the orientation of the coast.

Figure 8 a) Monthly beach profiles (Vistahermosa and Centro) for 2016 and 2017. b) Predominant beach profile type in % for each year, sector, and profile. c) Beach profile type for each month and its corresponding morphodynamic state, marked with a red x.

Figure 9 a) Monthly beach profiles (Vistahermosa and Centro) for 2018 and 2019. b) Predominant beach profile type in % for each year, sector, and profile. c) Beach profile type for each month and its corresponding morphodynamic state, marked with a red x.

Type 1 (morphodynamic-erosive dissipative) was, in general, the predominant beach state during the sampling years (average: 35.1 %) and showed the highest presence in 2016 and 2019. The second most common state was type 3 (indermediate morphodynamic-non-erosive, average: 33 %), which was more frequent in 2015 and 2018. Type 2 reported an average of 17 % and was more frequent in 2014 and 2015. In the same period, the 4-A state (morphodynamic-erosive reflective) predominated, but it only represented 8 % of the Centro sector. The observed changes in the beach states and types regarding monthly variations indicate that the beach adapts rapidly to oceanographic conditions. On some occasions, marked changes are seen from one month to another, with significant beach morphology variations (profiles and DEMs). The beach does not exhibit the temporal framework necessary to adapt to changes; on the contrary, as mentioned before, it adjusts rapidly.

As for the maximum tide values in the intra-annual beach behavior, it would be expected that, in the months with increased tides, reflective beach states are observed, but this only happened in 2014 and 2015. It was evidenced that, with high or low tide values, the presence of dissipative and intermediate states is maintained (Figure 9). The interannual results show that in 2014 and 2015, when the tide reached its maximum values, reflective states were observed, represented by erosion processes. However, when the tide was low (2016-2019), dissipative and intermediate states were observed (Figure 10).

When the tide height exhibits values not higher than 4.5 m (2016-2019) in the Centro sector profile (inside the bay), an intermediate state is observed in the first months of the year, which becomes dissipative in the second half of the year. On the other hand, Vistahermosa always showed a dissipative state. another observation is that the relationship between the states and the tide is inverse. In 2014, and 2015, the beach state was dominated by the tide (TD), which implies an increase in the influence of the waves, that is, there is a larger beach area where the waves interact with the surface of the beach. After this, there are processes with no dominance of the waves.

DISCUSSION

The descriptions provided by the plan models of this research match the results and the different characteristics described by Correa and Restrepo (2002), who employed field observations to describe and propose a morphodynamic model of El Choncho beach (Colombian Pacific). These authors represented the main morphological characteristics and coastal processes, and they classified the beach as being in an intermediate morphodynamic state. These results agree with the beach profiles previously elaborated regarding the geoforms associated with barrier islands (Martínez and González, 1997). It is worth remembering that the plan models are adaptations of the proposed models and the morphological characteristics obtained from the generated DEMs, that is, the predominant morphological characteristics were collected and represented in models that had already been adapted by different authors.

The results of this study show a predominance of the dissipative and intermediate morphodynamic states in the macrotidal beach of La Bocana in the eastern tropical Pacific, with dominant TM and TD processes that coincide with those proposed by Short (2020) and previous authors (Masselink and Short, 1993; Masselink et al., 2006; Scott et al., 2011) for middle latitudes. These states are seasonally and interannually distributed and provide an approach for understanding the temporal beach rotation processes proposed by Loureiro and Ferreira (2020). The greatest intra-annual morphodynamic state changes (2014 and 2015) show a synergic effect between the tide range and the maximum wave height, with a transition towards mainly reflective profiles when the latter exceeds 0.7 m, and the period is short (between 5 and 9 s). This may be more critical in the study area in the face of extreme events, as maximum wave heights of up to 2.18 m have been reported (Portilla et al., 2015), which could translate into a loss of the coastline. This should be analyzed in future works.

This method groups chronologically and spatially the morphodynamic states of two beach profiles. Pereira et al. (2010) performed a homogenous and heterogenous grouping and a morphodynamic classification of a coastal segment more than 300 km in length. They identified the three states in this segment. Thus, the coastal area contains different spatial-temporal variation scales with regard to morphodynamic states.

A predominance of type-1 (dissipative-erosive) and type-3 (intermediate-non-erosive) profiles was observed. The states are dominated by the tide, with annual patterns that depend on the seasonal and interannual environmental stability of the tropical zone. This confirms the morphodynamic state classification proposed by Wright and Short (1984) and Masselink and Short (1993) for macrotidal beaches.

In the Vistahermosa sector (exposed area), there was a predominance of type-1 beaches (dissipateive), while, in Centro (internal bay area), type 3 (intermediate) was predominant. The wind speed and the wave height increase in the second semester of the year (Thomas et al., 2014; Ricaurte-Villota et al., 2018), but the beach shows no seasonal WD types nor states related with the climatology. A factor that may influence this relationship is not only the evident dominance of the tide, but also the fact that the Centro sector beach (internal bay area) is under anthropic influence due to the waves generated by the ships entering the port of Buenaventura, which alters the normal conditions of a possibly estuarine beach. On the other hand, Vistahermosa beach (exterior and exposed area), which should be correlated with the waves, shows a marked anthropic intervention, as concrete and wooden walls are built for protection against coastal erosion, which alters the normal conditions of a beach. This beach currently shows a (predominantly) dissipative state, which may have altered the results and perhaps does not allow visualizing the natural seasonal conditions, although it evidences the anthropic influence on the changes in beach morphodynamic states.

Morphodynamic beach classifications have been mainly carried out in middle latitudes, e.g., in the United Kingdom (Scott et al., 2011) and Australia (Masselink and Short, 1993; Masselink et al., 2006), under environmental conditions very different from those of the eastern tropical Pacific. The potential for high-energy WD beaches is greater in middle latitudes, as the wave height generally decreases in latitudes below 30° and above 60 ° (Davies, 1980). Sediments are also controlled latitudinally, and the tropics are dominated by an abundance of fine terrigenous sediments and low-energy reflective beaches (Short, 2020). Despite the tropical location and the variable environmental conditions, the classifications match those proposed for middle latitudes, which suggests the dominance of the tidal range in the determination of beach morphodynamic states.

This study did not employ mathematical analyses on multitemporal topographic data in order to determine morphological patterns with temporal and spatial variations (Winant et al., 1975; Miller and Dean, 2007a, 2007b; Conlin et al., 2020), as the main emphasis was the identification of morphological characteristics and carrying out a beach morphodynamic analysis, and, later, based on the results obtained, on temporally and spatially analyzing the beach states. It would be interesting, under another objective, to be able to adapt quantitative analyses m the perspective used in this study.

Another factor to be considered is the missing data corresponding to December, January, and February. The parameter Ω employed in this study can predict beach morphology with the predominant conditions. This is an advantage against these gaps in the data. Still, the sampling carried out for six (nine months for each one) constitutes a representative sample, considering the predominant natural conditions of the beach.

CONCLUSIONS

Four predominant beach types are proposed classified according to beach morphodynamics and states, characterized seasonally and according to the position of the beach, that is, one beach profile under external conditions and exposed to direct wave conditions (Vistahermosa sector) and one profile of the beach within the bay (Centro sector). It was observed that, in Vistahermosa beach, type 1 is predominant in a dissipative morphodynamic state, while Centro shows a predominance of type 3 in an intermediate state. Similarly, six plan models obtained from morphological observations are proposed.

In this macrotidal beach of the eastern tropical Pacific (La Bocana beach), the main result was a predominance of dissipative and intermediate morphodynamic states, with dominant MT and TD processes, thus suggesting a dominance of the tidal range in determining the beach morphodynamic states. In addition, the TD state observed in 2014 and 2015 shows a reflective beach front due to the possible increase in the waves caused by more energetic conditions.

The morphodynamic classification of beaches in the Colombian Pacific littoral and the determination of the causes for beach morphological changes on intra- and interannual scales contribute to understanding tropical beaches, upon the basis of elucidating the way in which they respond to environmental processes with intra- and interannual variations, e.g., the synergic effects between tides and waves, which may favor the rational development of coastal areas in the Colombian Pacific.

Finally, this work evidences the importance of monitoring coastal systems in situ. This first time series spanning six years of beach profiles and models for the eastern tropical Pacific and Colombia relates oceanographic and climatic variables, and it helps to understand spatial-temporal dynamics, although more frequent observations is required, given that the effect of external events is unknown. The results contribute to the regional and local knowledge of the beaches, as well as to aiding decision-makers, planners, institutions with regard to risk management.

text in

text in