SUMMARY

Introduction. 1. Setting the ground: Conceptual considerations and clarifications. 1.1. Defining judicial review. 1.2. Civic republican political theory. 2. The republican critique against judicial review. 2.1. The legitimacy of political decision-making: Procedural vs. substantive approaches. 3. A participatory conception of judicial review. 4. The participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review: A gradual approach. 4.1. The institutional context of judicial review and the intensity of the counter-majoritarian difficulty. 4.2. The institutional conditions of participatory judicial review. 4.2.1. Constitutional rigidity and constitutional amendment mechanisms. 4.2.2. Restrictions to the declarations of unconstitutionality: Required majorities in supreme/constitutional courts. 4.2.3. Rules of standing in supreme/constitutional courts. 4.2.4. The right to a voice: Who can intervene during processes of judicial review? 4.2.5. Selection rules for constitutional justices. Conclusions: Judges without robes. References.

INTRODUCTION

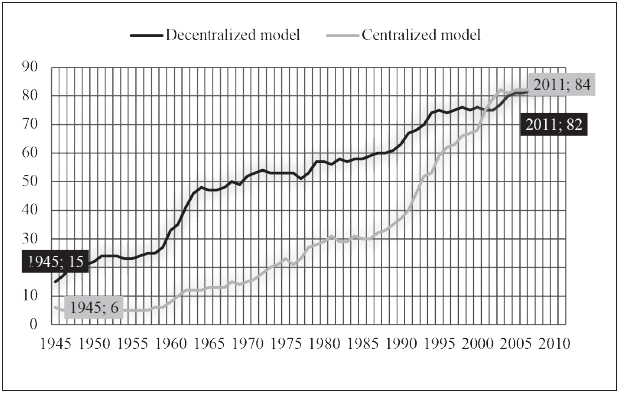

Judicial review is an institutional arrangement whereby the decisions made by democratically elected legislative bodies are subject to control and possible invalidation by the judiciary for being incompatible with the constitution1. Although judicial review emerged in the United States more than two hundred years ago, this institution has expanded its reach profusely in the last decades, in the context of the third wave of democratization2. According to data gathered by the Comparative Constitutions Project3, 10% of the world's constitutional systems incorporated a scheme of judicial review in their constitutions by the end of the Second World War. This number had risen to 82% by 2011, as shown in Graph 1 4.

Source: Own elaboration, with data from the Comparative Constitutions Project.

Graph 1 Number of constitutional systems with a scheme of judicial review incorporated in their constitution

The constitutional history of judicial review has been, thus, one of extreme success. But despite this, or perhaps precisely because of it, it has been the subject of stringent criticisms by jurists and political philosophers, who have challenged the legitimacy of judicial review because of its purported lack of democratic credentials. Broadly speaking, critics of judicial review argue that allowing the judiciary to invalidate decisions made by democratically elected legislatures produces a "counter-majoritarian difficulty"5, since putting the final decisional authority in the hands of non-elected bodies such as those belonging to the judicial branch ends up making void the democratic principle of majority rule.

Judicial review is an institution that fits within the contours of liberal legal systems which, as Samantha Besson and José Luis Martí explain, predominate in current advanced democratic societies6. It is no surprise, then, that some of the most stringent opponents of judicial review have formulated their criticisms from a perspective that can be read as republican. Essentially, republican critics of judicial review present a case for the fulfillment of the ideal of self-government through the institutionalization of procedures that allow the citizenry to exercise their right to political participation on equal terms by giving each of them the same weight in political decision making in a regime of legislative supremacy.

However, it is possible to make a case for judicial review that relies on republican political theory emphasizing the potential it has to promote political participation on equal terms by the citizenry, in a way that honors the republican ideal of self-government. In short, judicial review is compatible with republicanism, as I will argue here.

According to this aim, the paper is divided into five sections. Section i presents some considerations and clarifications regarding the concept of judicial review and the type of republican political theory that frames the main arguments of this paper. Section ii reconstructs the republican critique of judicial review. Section iii shows that subscribing to a republican perspective does not necessarily lead to the endorsement of this critique and presents a defense of judicial review that relies upon a republican conception of deliberative democracy that stresses the potential of this institution as a mechanism that serves to promote political participation in equal terms and that, thus, imbues judicial review with a participatory democratic legitimacy. Section iv argues that the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review should be seen as a gradual phenomenon whose relative strength or weakness depends on the variations of specific characteristics of the institutional context where the judiciary operates, such as the level of constitutional rigidity in place and the rules of standing that define who is entitled to trigger the process of judicial review. Section V offers some conclusions.

1. SETTING THE GROUND: CONCEPTUAL CONSIDERATIONS AND CLARIFICATIONS

The purpose of this section is to set the conceptual and theoretical ground for the subsequent discussion. With this goal in mind, I begin by presenting some considerations on the institution of judicial review. Against this backdrop, subsequently, I will engage with the type of republican political theory that serves as the theoretical framework of my argument.

1.1. Defining judicial review

The main concern of this paper is the judicial review of legislation in democratic regimes, that is, legislation enacted by popularly elected legislatures within democratic polities7. Judicial review is a heterogeneous institutional arrangement since different legal phenomena can be grouped under its heading. They can be distinguished along multiple dimensions, which are analytically separable even if they are empirically interrelated.

The first and foremost distinction is between (i) strong judicial review, where courts have the authority to decline the application of a specific statute in a particular case, to interpret it in a way that its application conforms to the constitution8, and even to definitively exclude entire pieces of legislation of the juridical order altogether; (ii) weak judicial review, where courts may scrutinize legislation and assess its constitutionality, but have no power to definitely exclude it from of the juridical order nor to decline to apply it, since legislatures are entitled to override the courts' decisions or are not obliged to comply with them since they are regarded as merely declarative9. Since weak judicial review does not imply the power to unquestionably invalidate legislative decisions, it is not subject to the counter-majoritarian difficulty to the same degree as strong judicial review. Accordingly, in what follows I will engage exclusively with strong judicial review.

The second distinction is between (i) the decentralized or "American" model of judicial review, by which any judge in the context of a concrete case can declare the unconstitutionality of a statute and decline to apply it, with effects only for the parties involved in the specific legal process (inter partes effects)10; and (ii) and the centralized or "European" model of judicial review, which allows for a specialized constitutional court to decide on the constitutionality of statutes in the context of abstract challenges to them, with general effects for the polity (erga omnes effects)11.

My case for judicial review will focus on the centralized model, as I intend to engage with the counter-majoritarian difficulty in its strongest version. Sebastián Linares has shown that the differences in the institutional design between both models incentivize the exercise of judicial review against "contemporary statutes" in the centralized model, and against "non-contemporary statutes" in the decentralized model. As a result, this increases the intensity of the counter-majoritarian difficulty in polities with centralized designs, as it facilitates the judicial strike down of democratically made decisions by currently existing legislative majorities12. Additionally, as seen in Graph 2, the centralized model has gained traction and is slightly more popular nowadays than the traditionally predominant decentralized one.

Source: Own elaboration, with data from the Comparative Constitutions Project.

Graph 2 Evolution of centralized and decentralized models of judicial review13

1.2. Civic republican political theory

Republicanism is a heterogeneous tradition in political theory of which two major and distinct strands can be differentiated. The first is known as the neo-Athenian or "humanist" one. It endorses the Aristotelian concern for the good life and claims that human beings can only realize their nature and achieve liberty through active participation in the political life of their self-governing communities. The second one, known as the neo-Roman or "civic" strand, subscribes to a conception of freedom according to which "liberty is not definitionally linked to political participation", but rather to the idea of not being subject to the whim or interests of others14. Civic republican political theory endorses an instrumental interpretation of civic virtue and, thus, of political participation as a means to avoid domination15. This particular position scaffolds the main discussions and arguments I suggest in this paper.

Philip Pettit is the most important theorist of civic republicanism in the context of contemporary political philosophy16, proposing an original understanding of freedom that situates itself between the liberal conception of negative liberty as freedom as non-interference and the communitarian conception of positive liberty as freedom as self-mastery through participation in the formation of a common popular will, which he calls "freedom as non-domination"17.

Freedom as non-domination is a demanding conception of liberty according to which human beings are not truly free simply because their choices are, at the moment, not being interfered with. The mere possibility of being vulnerable to alien interference by others makes persons unfree, even if the interference never actually takes place. In such situations, persons may act however they wish to, but only because those who have the power to interfere with their freedom decide not to, not because they are free of domination18.

Just as there can be domination without interference, there can also be non-dominating interference, namely, interference that does not imply any major loss of liberty. This occurs when the interference is not arbitrary, that is, "when it is controlled by the interests and opinions of those affected, being required to serve those interests in a way that conforms with those opinions"19. This is rather crucial in terms of institutional design, as civic republicanism endorses a political project where the state actively interferes in people's lives in non-dominating ways, seeking to track the citizenry's interests and opinions, to guard them against different sources of domination20.

Two sorts of power can induce domination and turn the individual into a servant to other peoples' whims and desires. The first one is the private power of other persons or groups and is called dominium. The second one is the public power of the state and is called imperium. The challenge of the civic republican political project is to reflect on an institutional structure of government that serves to guard people against the private power of others, and thus avoid dominium, without becoming itself a source of domination in the form of imperium. Protection against dominium is achieved through the establishment of a social-democratic order where the distinctly vulnerable are provided with the resources of basic functioning and where powerful individuals and agencies are regulated so that they are not entitled to exercise alien control over ordinary citizens. Protection against imperium is achieved by the establishment of a system of government whose initiatives and policies are subject to a sort of popular control where citizens take part on equal terms, allowing them to contest public decisions when they have reasons to believe that these policies fail to track their interests and ideas21. I will come back to this discussion in Section III.

2. THE REPUBLICAN CRITIQUE AGAINST JUDICIAL REVIEW

In this Section, I reconstruct a critique of judicial review that can be read as inspired by civic republicanism. I rely on republican authors such as Richard Bellamy and Adam Tomkins. I also recur to a thinker that is more a liberal than a republican: Jeremy Waldron. I draw on Waldron's arguments for two reasons. Firstly, because he is the most relevant philosophical opponent of judicial review and at least part of his arguments can be interpreted in a way that is compatible with republicanism22. Secondly, because he has explicitly argued against judicial review from a republican perspective23. It is true that in the piece just quoted he characterized the "approach that many self-styled republican theorists take today" as "sort of hunt-and-peck" and "sophomoric"24, but he nevertheless developed a civic-republican charge against judicial review that is worth considering.

Although these authors arguments differ in important considerations, they agree on their understanding of judicial review as an undemocratic institutional arrangement that gravely undermines the democratic principle of majority rule. They, thus, present a case for a regime of legislative supremacy, where decisions made by legislatures cannot be reviewed and overridden by the judiciary. I begin by discussing the difference between substantive and procedural approaches to the legitimacy of political decision-making, and then I proceed to present the republican critique of judicial review as a weak proceduralist defense of majoritarian democracy realized in elected legislatures.

2.1. The legitimacy of political decision-making: Procedural vs. substantive approaches

When discussing the legitimacy of political decisions, there are two competing approaches: (i) substantive and (ii) procedural. While the former argues that the legitimacy of a political decision is based on its content, the latter contends that the legitimacy of a decision derives from the procedures whereby the decision was arrived at. These approaches are both unsatisfactory if understood in radical ways. On the one hand, if one endorses the idea according to which procedure is all that matters when discussing legitimacy, how does one know which procedure is adequate for political decision-making? Should we go for majority rule or perhaps for coin tossing? If we believe in democracy, we should prefer the former instead of the latter, but we cannot arrive at that conclusion without embracing a substantive dimension of political justification that tells us that democracy and majority rule embody the adoption/promotion of certain cherished values, such as political equality. On the other hand, if one endorses a pure substantivist approach, one still has to explain how it is that society can arrive at political decisions that are legitimate exclusively in terms of their content, which can only be done by discussing the proper procedures for such a task.

This does not mean that the distinction between procedural and substantive approaches to legitimacy is useless or nonexistent, but rather that we should reject radical proceduralism and radical substantivism, and instead conclude that any satisfactory conception of the legitimacy of political decision-making ought to combine procedural and substantive criteria. "To be legitimate, a political decision must have been taken following a determined procedure recognized as legitimate, and also be respectful in some sense with certain substantive values of justice"25. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the mixed conception of legitimacy as a middle ground between pure proceduralism and pure substantivism.

2.2. Disagreement and majoritarian democracy in legislatures

The republican critique of judicial review relies on a conception of political legitimacy that should be understood as procedural in a weak sense. Even though it emphasizes the importance of procedures as the main source of legitimacy in political decision making, the defense of the sort of procedures fostered by this perspective relies on their ability to express values such as the equal dignity and autonomy of individuals through political equality26.

In a similar vein to John Rawls27, Waldron begins his argument by saying that disagreement is one of the defining features of social and political life.

However, pace Rawls, Waldron contends that we do not only disagree about the good but also justice and rights. "There are many of us, and we disagree about justice. That is, we not only disagree about the existence of God and the meaning of life; we disagree also about what counts as fair terms of cooperation among people who disagree about the existence of God and the meaning of life"28.

The fact of disagreement is unavoidable and unsurmountable in democratic societies, for disagreement about justice is not based on bad faith, self-interest, or cognitive deficiencies, but rather is a consequence of the burdens of judgment29 to which we are all subjected, and which apply as much in matters of justice as in issues of the good30. But despite this, societies need to reach common decisions and courses of action on different sorts of justice-related matters, even in the face of disagreement regarding them, a fact that Waldron labels as the circumstances of politics31. The challenge is, then, to decide which sorts of procedures are better suited to allow societies to deal with the fact of disagreement and the circumstances of politics, and to make collectively legitimate decisions on issues related to justice and rights.

Bellamy, drawing on Waldron's discussion of disagreement and Pettit's conception of freedom as non-domination, poses that under conditions of unescapable disagreement a legitimate political decision-making procedure ought to satisfy two criteria to be considered of non-dominating nature. First, citizens will need to feel that there is no difference in status between them and decision-makers, which means that decision-makers should not be selected because they are deemed to be superior to other members of the citizenry in some respect. Second, the procedure should not give more weight to the opinion of some citizens on the ground that they are more likely to hold the "right" view on one or several specific matters. The procedure of judicial review falls short on both of these requirements, for judges exercising it claim a superior status on account of the unjustified assumption that they are more likely to be right than other citizens, making "those on the bench more equal than the rest"32.

In a similar spirit, while discussing the legitimacy of judicial review, Waldron claims that a republican conception of government involves a profound commitment to the value of political equality among the citizenry. Honoring political equality requires limiting the sort of arguments that can be offered for justifying political inequalities in decision-making, such as appealing to the idea of "the best ruler" or to any sort of procedure that is based on the idea that it serves the citizens' interests, but excludes them from taking part in decision-making. And, for Waldron, that is exactly what judicial review does and is the reason why it should be rejected from a civic republican perspective that "advocates that we take a chance on a people's ability to govern themselves"33.

What sort of procedures, then, can satisfy the requirements of political equality and freedom as non-domination? For Bellamy, freedom as non-domination requires a political system that gives equal weight to each individual in political decision making and this can only be done by establishing an impartial process for deciding between individuals' frequently opposing claims34. Regular elections based on the one person one vote principle, majority rule, and a competitive party system, are three features present in contemporary democratic systems that "provide a system whereby every view gains an equal airing in ways that oblige each of them to 'hear the other side'"35.

Tomkins presents a distinction between "political constitutionalism" which privileges "political forms and institutions of accountability", and "legal constitutionalism" which privileges "legal forms and institutions of accountability"36, and puts forth a defense of the former against the latter. For political constitutionalists, "the appropriate forum for the resolution of political conflicts is a political forum and cannot be the courtroom"37. This does not imply that the institution of judicial review should be abolished, for narrowly defined and absolute rights (such as an absolute ban on torture) ought to be judicially protected. But when qualified political claims that can be subject of disagreement (such as the meaning and limits of freedom of expression) are consecrated as substantive judicially enforceable rights, things become problematic for they are withdrawn from their appropriate forum of discussion: the political process in Parliament. In this sense, the courts' "overall constitutional role [...] should be to support and nourish the political constitution [...] by referring questions [such as political claims that can be subject of disagreement] back to Parliament"38.

Waldron, on his part, argues that majority rule in legislatures is the only decision-making procedure that properly respects the individuals whose votes it aggregates. First, it fully respects each individual's opinions about justice and the common good by rejecting any aspiration for consensus and by giving each vote the same weight. Second, it symbolizes a principle of respect for each person by establishing that society will settle on the collectively adopted view, not because it is in some sense superior, but only because it was the result of a procedure that respects political equality, even in the face of persisting disagreement39. In this sense, where democratic political institutions and judicial institutions function relatively well, there is widespread social support for individual rights -even though there are deep disagreements about the nature and content of rights-, polities "ought to settle the disagreements about rights that its members have using its legislative institutions", for "the case for consigning such disagreements to judicial tribunals for final settlement is weak and unconvincing"40.

3. A PARTICIPATORY CONCEPTION OF JUDICIAL REVIEW

In this Section, I present and defend a participatory understanding of the institution of judicial review. I start by discussing the classic case for judicial review posed by civic republicanism, showing why it remains vulnerable to the republican critique. Then, I proceed to present a defense of judicial review that relies on a republican conception of deliberative democracy that stresses the potential of this institution as a mechanism that serves to promote political participation on equal terms, imbuing judicial review with a participatory democratic legitimacy. I close the Section by discussing and responding to a possible objection to the participatory understanding of judicial review.

3.1. Civic republicanism and judicial review

As I argued in Section I of this paper, civic republican political theory faces the challenge of reflecting on the governmental structure that serves to guard people against the private power of others, and thus to avoid dominium, without becoming itself a source of domination in the form of imperium. In other words, we need to think about the sort of institutional design by which the state will be able to interfere with peoples' freedom in non-dominating ways. That is: a system of legal rules that forbids the exercise of arbitrary power by public officials.

Authorities will exercise arbitrary power if their decisions fail to track the interests and ideas of the citizens it affects, and instead are based on the private and/or sectional interests and ideas of public officials. If authorities can base their decisions on their private or sectional preferences, citizens will be dominated, as their own interests will be subjected to the whim and desires of those who hold the power to interfere with their freedom when they see fit to do so. Republican freedom as non-domination requires, thus, doing something to guarantee that public decision-making tracks the interests and the ideas of the citizenry affected by it41.

To achieve a tracking relationship that ensures the non-arbitrariness of public decisions, citizens need to be able to contest governmental decisions when they have reasons to believe that they conflict with their interests and ideas. This can only be achieved through a type of democracy that has two dimensions: authorial and editorial. The authorial dimension requires that governmental action is positively oriented through electoral institutions towards the common recognizable interests of the people, while the editorial dimension demands the existence of appellate resources that serve to negatively scrutinize laws and policies so that those that do not answer to common interests can be challenged and eliminated42.

This is why Pettit suggests that democracy ought to be understood through a contestatory model rather than a consensual one. In his words, "[o]n this model, a government will be democratic, a government will represent a form of rule that is controlled by the people to the extent that the people individually and collectively enjoy a permanent possibility of contesting what government decides"43. A contestatory democracy requires the satisfaction of the three following criteria:

A basis for contestation. Public decision-making that is contestable in a republican manner will necessarily be based on the ideal of deliberative democracy, as deliberative decision-making entails that citizens will be able to contest governmental decisions by appealing to the force of the better argument, and not to their own bargaining powers.

A voice for contestation. A contestatory democracy will not only be deliberative, but inclusive, meaning that each citizen or group needs to be given a voice so that they become potential contestators. Effective channels for complaining and appealing governmental decisions are, thus, necessary.

A forum for contestation. For a democracy to be contestatory, the polity must not only be deliberative and inclusive but also responsive. That is, the citizenry must be guaranteed a forum where their contestations against governmental decisions can receive a proper hearing, through the institutionalization of procedures that allow for this.

More importantly, there are different sorts of contestations where popular debate would be inadequate to promote a deliberative, inclusive, and responsive discussion regarding complaints against public decisions, since politicized forums can obstruct rational and calm deliberation44. In such cases, the editorial dimension of contestatory democracy demands that complaints are depoliticized and heard away from "the tumult of popular discussion and away, even, from the theatre of parliamentary debate", and taken to the quiet of "the quasi-judicial tribunal", where the "political voices have been gagged" and "the contestations in question can receive a decent hearing"45. In terms of institutional design, this implies an endorsement of judicial review as an important resource of democratic contestation46.

This is, thus, how classic civic republicanism can embrace judicial review as a mechanism of democratic control that allows the citizenry to contest governmental decisions. The problem with this defense is that it is vulnerable to precisely the criticisms posed by Waldron, Bellamy, and Tomkins who regard this understanding of judicial review as a depoliticized contestation mechanism as undemocratic since it gives way to a mode of citizen participation "undisciplined by the principles of political equality" that allows some to get more influence than that which electoral politics affords47.

3.2. Judicial review as a participatory institution

We seem to be trapped in a sort of republican argumentative stalemate between two opposing understandings of judicial review and its proper role in a republican system of government. There is, however, a way to integrate Waldron's, Bellamy's, and Tomkins's concern for democratic participation and majority rule, and Pettit's defense of contestatory mechanisms that allow the citizenry to contest any sort of governmental decisions, including those made by legislatures.

In her discussion of the compatibility of judicial review with a republican system of government, Iseult Honohan criticized Waldron's, Bellamy's, and Pettit's stances on the matter. Even if they reach opposing conclusions, Honohan argues, they all take limited popular participation in electoral and representative politics for granted: Waldron and Bellamy in their defense of the supremacy of legislators, and Pettit in his case for a depoliticized type of contestation through judicial review. In her view, strong judicial review is compatible with "a more participatory republicanism", not because of any alleged epistemic superiority of judges, but rather because supreme/constitutional courts should be understood as one of several deliberative institutions which operate in the framework of a wider political process composed of multiple spheres of deliberation in an articulated polity. Judicial review should be seen as a constraint "less on the people than the legislature, less on popular sovereignty than on legislative sovereignty", and thus "provide one element of the institutional realization of republican non-domination and self-government"48. To achieve that, we need to reframe the way we understand the right to legal contestation through judicial review to frame it as a participatory institution that operates within the framework of a well-functioning deliberative democracy, serving to promote political deliberation among free and equal citizens, rather than as an instrument that serves to depoliticize contested issues.

Drawing on Pettit's conception of republican liberty, Alon Harel argued that freedom as non-domination "does not merely require that the legislature refrain from violating rights but also that it is bound to do so" by the entrenchment of rights in the constitution49. In a polity where the legislature refrains from violating rights due to its judgements or inclinations, citizens might be free of interference but still "living at the mercy" of the legislature's will. In contrast, in a regime where the legislature is constitutionally forbidden to encroach upon individual rights, citizens are not only free of interference but also of domination50. Now, to effectively secure the protection of rights individuals ought to be entitled to "a right to a hearing" which "consists of a duty on the part of the state to provide the right-holder an opportunity to challenge the infringement, willingness on the part of the state to engage in moral deliberation" and provide an explanation, and a willingness to reconsider the presumed violation in light of the deliberation51. The embodiment of such a right is judicial review. In this sense, "[t]here is no inherent conflict between equal democratic participation and the right to judicial review, because the right to a hearing provides a fair opportunity for any victim of an infringement to participate in the deliberation leading to the infringement of her rights"52.

Harel's argument is powerful and attractive, but still insufficient for the reframing of judicial review I am trying to elaborate. Harel claims that the virtue of his conception of judicial review is that it "constitutes the hearing owed to citizens as a matter of right"53, but he explicitly rejects the idea that it could be justified because of its potential to promote democracy or political deliberation. In short, it remains a depoliticized understanding of judicial review that is at odds with my proposal and that remains vulnerable to the republican critique.

In Democracy without shortcuts, Cristina Lafont puts forth a participatory conception of deliberative democracy, a proposal that seeks to increase citizens' "ability to participate in forms of decision-making that can effectively influence the political process such that it once again becomes responsive to their interests, opinions, and policy objectives"54. Here, I will frame this perspective as proceduralist in a weak sense, because -despite engaging with both procedure and substance of political decision-making- I intend to prioritize its procedural considerations. This is in line with a republican-deliberative perspective that assumes that an open, continuous, and revisable deliberative decision-making procedure has "pragmatic priority" over substantive concerns56. In the remainder of this subsection, I will draw on Lafont's book to put forth a republican participatory interpretation of judicial review that, in my view, can help overcome the republican argumentative stalemate aforementioned. Before proceeding, however, a discussion of my republican interpretation of Lafont's arguments is due because her intellectual commitment is to the ideal of deliberative democracy, not to civic republican political theory.

Deliberative democracy is a theory of democracy that is based on an ideal in which people discuss the political issues they face and, based on those discussions, make decisions regarding the policies directed to deal with matters of common concern that affect their lives. The theory, as its name suggests, is committed to the notion of deliberation, which is understood as "mutual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values, and interests regarding matters of common concern "[original italics]"57. Deliberation, then, is crucial for this democratic theory. But deliberation among who? Experts? Judges and legislators? The citizenry at large? I believe that if we are truly committed to the democratic component of deliberative democracy, we must strive for a republican and participatory interpretation of the ideal of deliberation.

Martí has explained that there are several justifications for deliberative democracy from a normative perspective and that two of them are of special relevance: (i) the epistemic justification, and (ii) the substantive justification58. The epistemic justification claims that deliberative democracy is a valuable ideal because deliberation is a "potentially powerful epistemic engine" that maximizes the probabilities of "getting to the correct or right decision or at least getting as close to it as possible"59. The substantive justification "uses certain substantive values, such as equal autonomy, political equality or mutual respect, to say that the procedure of deliberative democracy honors them better than any other procedure"60.

Crucially for the main argument of this paper, I side with Martí when he proposes a mixed normative model of deliberative democracy that is concerned with both its epistemic and substantive dimensions. Deliberative democracy is epistemically justified because it maximizes our chances to reach correct decisions better than other alternative democratic models. But to avoid the risk of letting our epistemic concerns slide us towards an elitist interpretation of deliberative democracy, we need to counter the elitist drive with a civic republican interpretation of the ideal that proposes to "convert political deliberation into public, encouraging not only institutionalized mechanisms for deliberative citizen participation that complement existing representative structures but also informal and non-institutionalized deliberation "[italics added]"61.

In short, although civic republicanism and deliberative democracy don't always go in tandem, "[d]eliberative democracy provides the institutional means by which the preservation of republican freedom through a virtuous exercise of political rights of citizenship may obtain"62. Not any version of deliberative democracy, of course: Elitists' interpretations of the ideal are out of the civic republican house, but Lafont's participatory conception of deliberative democracy is more than welcome.

Participatory deliberative democracy follows civic republicanism in important respects, as it is interested in avoiding domination. As I argued in previous sections, domination needs to be confronted with political equality, since non-domination is achieved by the establishment of a system of government where governmental initiatives are subject to a sort of popular control where citizens can take part in equal terms in the exercise of that control. But participatory deliberative democracy goes beyond the traditional concerns endorsed by civic republicanism, for it is also preoccupied with political alienation, which requires more than an equal distribution of power among the citizenry to be avoided.

Citizens have a fundamental interest in not having to live in a society whose laws and policies fail to conform to their considered judgments about justice. When citizens are unable to endorse obligatory laws and policies as just -because they consider them violating their fundamental rights and freedoms or those of other citizens- they might end up seeing themselves as being forced to acquiesce with injustice. In this sense, participatory deliberative democracy rejects the possibility that citizens are obliged to blindly defer to political decisions that they cannot reflectively endorse as just or at least as reasonable.

The focus on citizens' substantive concern with the content of the laws explains why the democratic ideal of self-government is not only concerned with non-domination through political equality but also with non-alienation through political participation in public decision-making. A democratic political system in which citizens can participate in shaping the laws and policies that apply to them is the only one that can guarantee that those laws and policies will adjust to their own considered judgments about justice. In this sense, democratic political participation in decision-making is necessary to avert an alienating disconnect between public opinion and political decisions, i.e., laws and policies. In Lafont's words:

Democracy must be participatory, but not in the sense of requiring citizens to be involved in all political decisions. Instead, a democracy must be participatory in the sense that it has institutions in place that facilitate an ongoing alignment between the policies to which citizens are subject and the process of political opinion -and will-formation in which they (actively and/or passively) participate. Citizens can defer a lot of political decision-making to their representatives so long as they are not required to do so blindly. So long as there are effective and ongoing possibilities for citizens to shape the political process as well as to prevent and contest significant misalignments between the policies they are bound to obey and their interests, ideas, and policy objectives then they can continue to see themselves as participants in a democratic project of self-government63.

It is through public deliberation that citizens can discuss the merits of laws and policies and, thus, reflectively endorse or reject them. Democratic legitimacy is, then, the product of an inclusive and ongoing process of will formation in which "participants can challenge each other's view about the reasonableness of the coercive policies they all must comply with", and give and receive mutual justifications based on reasons and arguments that can be regarded as acceptable by all the participants in the deliberative process64.

Participatory deliberative democracy adopts an institutional approach to the requirement of mutual justification which demands that institutions are in place to enable every citizen to contest any laws and policies they find unreasonable by demanding that appropriate reasons for them are offered. This does not mean that citizens will agree with every law and policy, as this would render the model implausible and unrealizable. What citizens need is the institutionalization of "effective rights to political and legal contestation that empower them to trigger a process of public justification of the reasonableness of any policies they find unacceptable"65.

In the institutional scheme of participatory deliberative democracy, judicial review plays a crucial role as an institutional arrangement that empowers citizens to trigger a process of public justification of laws that they find unjust or unreasonable and, thus, facilitates the ongoing alignment between considered public opinion and the laws and policies to which citizens are subjected to, as I explain in what follows.

In her discussion of the role of judicial review in a participatory deliberative democracy, Lafont begins by pointing out that the debate on the democratic legitimacy or illegitimacy of judicial review has been pervaded by two framing assumptions: (i) a juricentric perspective that focuses almost exclusively in the internal working of the courts and that fails to pay sufficient attention to "the political system within which the courts operate and where they play their specific institutional role", and (ii) a synchronic perspective that exclusively focuses on "how the courts can uphold or strike down a piece of legislation as unconstitutional at a particular point in time"66. This combination of institutional and temporal narrowness is problematic, as it leads to the analytic neglect of the active role of citizens in the process of judicial review, by critics and defenders of the institution alike.

The crucial point, however, is that in many polities judicial review is a process that is activated by the exercise of citizens' right to legal contestation that allows them to contest governmental decisions when they consider that those decisions fail to endorse their considered judgments about matters of justice. This triggers a process of public justification of the contested laws and policies. The right to legal contestation does not give decision-making authority to the citizens that use it, as they are not entitled to decide how the case is to be solved. Its power is more modest since it is limited to providing citizens with the right to be listened to. This entails a right to trigger a process of mutual justification in which their arguments regarding the constitutionality of a specific statute receive appropriate scrutiny, such as the one deserved by free and equal citizens who have the moral power to develop and maintain a sense of justice.

The right to legal contestation resembles Pettit's account of judicial review as an editorial mechanism that serves to depoliticize contested issues to give them a decent hearing away from the turmoil of politics67, and Harel's right-to-a-hearing conception of judicial review68. However, pace Pettit and Harel, Lafont argues that the exercise of the right to legal contestation through judicial review, far from being functional to depoliticize difficult moral and political discussion, serves to constitutionalize political debate in terms of fundamental rights and freedoms, fulfilling a proper democratic function69. Judicial review is, thus, a "conversation initiator" that can be seen as a political form of citizen involvement.

Contra Waldron, who regards judicial review as "a mode of citizen involvement that is undisciplined by the principles of political equality" that allows some to achieve more influence than that which electoral politics affords70, Lafont argues that as long as the path to legal contestation is open to all citizens, there is no reason to accept that judicial review disrespects political equality. Furthermore, since legal contestation limits itself to giving citizens the right to be listened to, it cannot be said that it somehow imbues them with a decisional influence such as the one that lies in the exercise of the right to vote71.

In the participatory conception of deliberative democracy, judicial review is, hence, a crucial element of its institutional design, and one that serves to honor the republican ideal of self-government in a way that imbues this institutional arrangement with a participatory democratic legitimacy. As Lafont puts it:

From a holistic and diachronic perspective, the democratic contribution of judicial review is not that the courts undertake constitutional review in isolation from the political debate in the public sphere. On the contrary, from a democratic perspective, the main contribution of the institution is that it empowers citizens to call upon the rest of the citizenry to publicly debate the proper scope of the rights and freedoms they must grant one another to treat each other as free and equal so that the protection of those rights and freedoms takes proper priority over other types of considerations (e.g. religious or otherwise comprehensive) that relate to the practices at hand about which citizens strongly disagree. Far from expecting citizens to blindly defer to the decisions of judges, the democratic significance of the institution is that it empowers citizens to make effective use of their right to participate in ongoing political struggles for determining the proper scope, content, and limits of their fundamental rights and freedoms -no matter how idiosyncratic their fellow citizens think their interests, views, and values are. By securing citizens' right to legal contestation judicial review [...] offers citizens an institutional venue to call their fellow citizens to account by effectively requesting that proper reasons be offered in public debate to justify the policies to which they are all subject, instead of being simply forced to blindly defer to their decisions72.

3.3. Judges as conversation initiators? Participatory judicial review within a deliberative system

Before proceeding to the next section, I want to discuss a possible objection to the approach I am proposing. It goes as follows:

"Reframing judicial review as a conversation initiator that can be seen as a political form of citizen involvement sounds indeed very nice, but it is bound to fail. Constitutional courts cannot fulfill that function for they are not the proper forum for citizen participation. The language used by courts forces participants to translate their moral and political claims into legal ones and that excessively narrows the scope of concerns that can be brought to the judicial forum. This impedes them to operate as genuine conversation initiators in a participatory deliberative democracy"73.

Several authors have put forth arguments that give force to this objection. Bellamy posits that "the judiciary are limited in their deployment of moral and social scientific arguments to those that can be accommodated within legal discourse"74. Waldron puts it in the following terms: "The questions about rights, which are the subject matter of the controversy regarding judicial review, are, in my view, mostly not issues of interpretation in a narrow legalistic sense [...] They define the major choices that any modem society must face, choices that are the focal points of moral and political disagreements in many societies"75. The problem is that judicial review hinders genuine discussions of such moral and political disagreements, since "the real issues at stake in the good-faith disagreement about rights get pushed to the margins"76.

Furthermore, Donald Bello Hutt77 has warned against the tendency to idealize constitutional courts as ideal deliberative sites, a tendency that can be found in the writings of authors such as Rawls78, Habermas79, Eisgruber80, and Ferejohn and Pasquino81 among others. To elaborate his argument, Bello Hutt draws on Conrado Hübner Mendes' s articulation of an "ideal-type deliberative court" that performs a series of differentiated "deliberative tasks" in the pre-decisional, decisional, and post-decisional phases of processes of judicial review82. In Hübner Mendes's scheme, two types of deliberators interact : judges and interlocutors, that is, "all social actors that, formally or informally, address public arguments to the court and express public positions as to the cases being decided"83.

Bello Hutt argues that "the more the procedure moves from the pre-decisional to the post-decisional phase, the less room there is for the interlocutors to participate"84. Moreover, due to the opacity of judicial proceedings, it is extremely difficult, if not straightforward impossible, to know anything about the deliberative quality of deliberation in the decisional phase. And in the pre- and post-decisional phases, "the participation of the interlocutors is not fully deliberative: parties are either sources of inputs in an adversarial, non-dialogical sense, as they do not discuss with the expectation of changing each other's convictions or preferences, or they are passive addresses of the court's decision"85.

The objection is no doubt powerful. But I think it can be answered by introducing an amendment to Lafont's theory of judicial review. Lafont's democratic reframing of judicial review is utterly brilliant, but it has, in my view, a fundamental flaw: It is affected by a problem of deliberative over-demandingness.

Lafont argues that "the main way judicial review contributes to political justification is that it empowers citizens to call the rest of the citizenry to put on their robes to show how the policies they favor are compatible with the equal protection of the fundamental rights and freedoms of all citizens -something which they are committed to as democratic citizens "[original italics]"86. To call the rest of the citizenry to put on their robes before the constitutional court, citizens are expected to uphold stringent deliberative standards: those proper of public reason-based justifications. If "citizens endorse the institutions of constitutional democracy", Lafont tells us, "this means they should behave like they expect the court to behave, that is, they should strive to meet the same standards of scrutiny and justification characteristic of public reason that the exemplar they have instituted is supposed to meet "[original italics]"87. The problem is that Lafont's robes might be too heavy, at least for some citizens. By introducing a public reason constraint as a requirement for the triggering of the process of judicial review, Lafont ends up supporting a scheme in which only citizens in robes, "which is to say citizens striving for neutrality in debating and forming opinions about constitutional rights"88, participate in participatory deliberative democracy. This, in turn, ends up producing a sort of Ackermanian constitutional dualism between "constitutional politics" and "everyday politics" that leaves ordinary law-making, and the "anarchic public sphere of mass democracies" out of the picture of deliberative democracy89, in a way that seriously diminishes the participatory potential of judicial review90.

I propose to counter this problem of deliberative over-demandingness by recurring to Linares's91 model of epistemic participatory democracy. Linares gives deliberation a "primary function" and a "privileged place" in the model but also considers "that the citizens' right to control the agenda and to take part on an equal footing in all relevant decisions is inalienable, and that means opening the door to informed mass participation, even if it is not deliberative [original italics]92. I believe Lafont's theory can be modified to allow for some degree of non-deliberative citizen mass participation in the exercise of the right to legal contestation through judicial review. I reject Lafont's claim that asserts that if "citizens endorse the institutions of constitutional democracy, this means they should behave like they expect the court to behave"93. The deliberative performance we should demand of constitutional courts is not the same as the one we should expect of citizens that seek to trigger processes of judicial review, for the latter ought to be allowed to participate through means that are not necessarily fully deliberative to foster the participatory potential of judicial review. This claim needs to be understood from a systemic approach to deliberative democracy.

Deliberative democracy has always been haunted by an objection: the problem of scale. Critics have questioned the deliberative paradigm by pointing out that the ideal that underlies it might be applicable in small-scale face-to-face deliberation, but completely unfeasible for large-scale mass democracies. Habermas's seminal articulation of the two-track model of deliberative democracy recognized this problem and sought to overcome it by pointing out that deliberative democracy doesn't demand constant face-to-face deliberation among the citizenry, but rather the existence of communication and transmission fluxes between opinion formation in the informal public sphere and will formation in public institutions so that public decisions can be traced back to society's "communicatively generated power"94. This systemic approach to deliberative democracy was further elaborated by Jane Mansbridge, who was the first to properly employ the term "deliberative system". In an attempt to extend the potential of the deliberative paradigm of democracy, she proposed that "the criterion for good deliberation should be not that every interaction in the system exhibits mutual respect, consistency, acknowledgment, open-mindedness, and moral economy, but that the system [as a whole] reflect those goods"95. This underlying idea has been further enriched, among others, by notions such as Robert Goodin's "distributed deliberation" in which "the component deliberative virtues are on display sequentially, over the course of this staged deliberation involving various components parts"96, and John Dryzek's "deliberative capacity" that is "defined as the extent to which a political system possesses structures to host deliberation that is authentic, inclusive, and consequential"97.

Perhaps the best articulation of the systemic approach to deliberative democracy is the one put forth in an essay coauthored by some of the most recognized deliberative democracy scholars of the last three decades: Jane Mansbridge, James Bohman, Simone Chambers, Thomas Christiano, Archon Fung, John Parkinson, Dennis Thompson, and Mark Warren98. In that pivotal work, they defined a deliberative system as "a set of distinguishable, differentiated, but to some degree interdependent parts, often with distributed functions and a division of labour, connected in such a way as to form a complex whole"99. A deliberative system, they claimed, "requires both differentiation and integration among the parts", "some functional division of labour, so that some parts do work that others cannot do as well"100. For Mansbridge et al., deliberative systems have three functions: (i) an epistemic function, related to the production of "preferences, opinions, and decisions that are appropriately informed by facts and logic and are the outcome of substantive and meaningful consideration of relevant reasons"; (ii) an ethical function, which "is to promote mutual respect among citizens"; and (iii) a democratic function, according to which deliberative systems are "to promote an inclusive political process on terms of equality"101.

The systemic approach to deliberative democracy allows for the introduction of diverse deliberative standards for different parts of the system. In this sense, behaviors that may individually be seen as non-deliberative can contribute to the overall deliberative quality of the system. "The purposes of institutions and their functions in collective decisions will often dictate differing internal constraints on deliberation [...] Judging the quality of the whole system on the basis of the functions and goals one specifies for the system does not require that those functions be fully realized in all the parts"102. The specification of differentiated deliberative standards is, of course, a thorny issue. But as a general rule of thumb, I propose assuming that "the more empowered the venue, the greater the need to justify departures from deliberative standards"103.

Taking this into account, it is possible to reframe the debate on the understanding of judicial review within deliberative democracy from a systemic perspective104. I claim that participatory judicial review, contra Lafont's stringent deliberative requirements, should allow for some degree of non-deliberative citizen participation before constitutional courts. This does not imply that any form of citizen participation ought to be seen as normatively acceptable from the perspective of participatory judicial review, but it does imply the rejection of the claim according to which if "citizens endorse the institutions of constitutional democracy, this means they should behave like they expect the court to behave"105.

This reframing of Lafont's participatory interpretation of judicial review allows me to overcome the objection outlined at the beginning of this subsection, for in the model I am putting forth participants are not required to translate their moral and political claims into legal ones. On the contrary, the formally empowered venues of the system -such as courts- are normatively required to make good-faith efforts to understand and process the demands of the less formally empowered actors, even if at first sight their interventions do not seem to be based on deliberative arguments.

4. THE PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRATIC LEGITIMACY OF JUDICIAL REVIEW: A GRADUAL APPROACH

In this Section, I contend that the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review needs to be understood as a gradual phenomenon whose relative strength or weakness depends on the variations of specific characteristics of the institutional context where the judiciary operates. I begin by debating the gradual approach to the intensity of the counter-majoritarian difficulty of judicial review, a discussion that resembles the one I intend to pose. Then, I proceed to discuss the institutional schemes under which the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review varies.

4.1. The institutional context of judicial review and the intensity of the counter-majoritarian difficulty

The problem of the counter-majoritarian difficulty of judicial review does not need to be understood as a debate between two extreme poles which raise competing and completely incompatible claims. On the contrary, this discussion should be approached by paying attention to the characteristics of the institutional context where judicial review operates, for contextual variations can lead judicial review to play distinct roles in different polities. As Lisa Hilbink has contended, defenders and critics of judicial review have both tended "to argue in dichotomous and/or essentialist terms", but we need to move beyond such binary perspectives to advance the theoretical development of the democratic legitimacy or illegitimacy of judicial review106. Luckily enough, several important authors have already moved in that direction.

Víctor Ferreres has argued that the counter-majoritarian objection against judicial review can have different levels of intensity, depending on the variations of three elements of the institutional context within which this institutional arrangement operates107. These are as follows:

Designation rules and terms of constitutional justices. The counter-majoritarian difficulty is stronger in systems where constitutional justices are selected by non-representative institutions and weaker in systems where democratically elected organs such as legislatures choose them or at least play a crucial role in their election. On the other hand, if constitutional justices have temporally limited terms, the counter-majoritarian objection is less intense than in the case of lifetime appointments.

Constitutional rigidity. The more rigid a constitution is, the more problematic it is to imbue a supreme/constitutional court with the power to review legislation since the difficulty to pass constitutional amendments under rigid constitutions in practice ends up instilling constitutional judges with the last word on political discussions. In contrast, constitutional flexibility weakens the counter-majoritarian objection to judicial review to the point of making it irrelevant in contexts of complete flexibility.

The interpretive controversy of the constitutional text or disposition. The more difficult it is to interpret a specific constitutional disposition, the stronger the counter-majoritarian difficulty, and vice versa. If a constitution explicitly forbids the death penalty and a statute permitting the death penalty is approved, it is practically irrelevant who is entitled to review the passed legislation, for it is straightforwardly evident that it goes against the constitution. But if a constitution protects the right to life and a statute permitting abortion is approved by the legislature, the counter-majoritarian objection takes its full force.

In a similar vein, Martí claims that the counter-majoritarian difficulty only arises properly, or at any rate strongly, when the conditions of what he calls the "Strong Constitutionalist Formula" are in place. If one of these conditions is not met, majorities are not completely blocked from taking decisions for the polity and, thus, the counter-majoritarian objection against judicial review loses at least part of its force108. These conditions can be subsumed as follows:

Significant counter-majoritarian constitutional rigidity. The constitution must be significantly rigid, and its rigidity ought to be counter-majoritarian, for constitutional rigidity is not per se counter-majoritarian. A constitution that can be reformed only by a constitutional referendum that requires an absolute majority is rigid and majoritarian. A constitution that can only be reformed by passing a supermajority amendment through the legislature, and that also needs to pass a posterior revision by a constitutional court of the content of the referendum is rigid and counter-majoritarian.

Strong judicial review. A rigid and counter-majoritarian constitution combined with a strong system of judicial review produces a regime of judicial supremacy where the "final word" on political matters effectively resides within the judiciary.

Perhaps one of the most ambitious attempts to analyze the intensity of the counter-majoritarian objection to judicial review through a gradual approach is the one posed by Linares, who puts forth nine institutional elements under which its intensity varies: (i) constitutional rigidity and constitutional amendment mechanisms, (ii) effects of rulings of unconstitutionality, (iii) designation rules for constitutional justices, (iv) restrictions to declarations of unconstitutionality within supreme/constitutional courts, (v) interpretative powers of legislatures, (vi) the right to a voice, that is, type and number of actors that are entitled to intervene in constitutional review processes, (vii) rules of standing in supreme/constitutional courts, (viii) the number of effective veto points to supreme/constitutional court's rulings by other actors in the political system, and (ix) contextual variables109. I will come back to the discussion of some of these elements in the following subsection.

4.2. The institutional conditions of participatory judicial review

In Section III, I drew on Lafont's participatory conception of deliberative democracy to argue in defense of judicial review as a crucial element of its institutional design that serves to honor the republican ideal of self-government in a way that instills this institutional arrangement with a participatory democratic legitimacy. To finish this paper, I will make use of the gradual approach to the intensity of the counter-majoritarian objection to suggest a mirroring perspective on the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review. In this way, I contend that the strength/weakness of this special type of democratic legitimacy varies depending on some institutional features of the polity.

It is important to note that this is an exploratory analysis that seeks to illustrate the soundness of my gradual approach to the participatory potential of judicial review. Since this is an initial approximation to this topic, the following considerations should be read as preliminary arguments that need to be further enriched in the future with empirical inputs that go beyond the reach of this paper. Here, I focus on the following constitutional variables: (i) constitutional rigidity and constitutional amendment mechanisms, (ii) restrictions to declarations of unconstitutionality within supreme/constitutional courts, (iii) rules of standing in supreme/constitutional courts, (iv) the right to a voice, and (v) selection rules for constitutional justices.

4.2.1. Constitutional rigidity and constitutional amendment mechanisms

Honohan and Lafont coincide in pointing out that a strong system of judicial review cannot be equated with the idea of judicial supremacy, since constitutional judges do not have the final word to determine questions of justice and rights, because they have no authority to amend or prevent the amendment of the constitution110. Even though this might always be nominally true, in practice the path of promoting a constitutional amendment depends on the level of constitutional rigidity in place111.

Linares suggests the following typology of constitutional rigidity: (i) flexible constitutions, which are those that can be changed by the same procedure whereby ordinary legislation is passed; (ii) rigid majoritarian constitutions, which are those with aggravated constitutional amendment procedures (e.g., a higher number of compulsory debates) that nevertheless require only absolute majorities to be passed; and (iii) rigid supermajoritarian constitutions, which are those with aggravated constitutional amendment procedures, and that also demand some sort of supermajority to be approved112.

The participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review is strong under flexible and rigid majoritarian constitutions, but it is difficult to state which sort of arrangement better fosters the participatory potential of judicial review without additional empirical research. The participatory understanding of judicial review is based on the idea that it can serve to trigger a process of mutual justification where the arguments of the litigants regarding the constitutionality of a specific statute receive appropriate scrutiny -such as the one that is deserved by free and equal citizens who have the moral power to develop and maintain a sense of justice- but who were unable to make their voices be properly heard in the legislature. Under flexible constitutions, judicial review could lose the power to act as a "conversation initiator", since legislative majorities may have no incentive to listen to the litigants' arguments. But this would be contingent on other institutional design variables and political realities that require solid empirical research to be grasped properly. Rigid majoritarian constitutions, on the other hand, seem better suited to serve the function of allowing the citizenry to contest legislative decisions through the courts without annulling the decisive power of legislative majorities, which would still be able to insist on their decisions by passing a constitutional amendment through an aggravated, yet still majoritarian, procedure. This, yet again, depends on other institutional design and political variables that I cannot explore here.

In contrast, it seems reasonable to affirm that under rigid supermajoritarian constitutions, the balance of communicative power might end up being too inclined in favor of the litigants, because if their view is favored by the supreme/constitutional court, the debate would be, in practice, foreclosed. In schemes of rigid supermajoritarian constitutions, the risk that judicial review ends up being a "conservation finisher" instead of a "conversation initiator" is not negligible.

4.2.2. Restrictions to the declarations of unconstitutionality: Required majorities in supreme/constitutional courts

In one of his multiple papers on judicial review, Waldron begins by posing a simple, yet powerful, question: "Why, in most appellate courts, are important issues of law settled by majority decision? Why, when judges disagree, do they use the same simple method of 'counting heads' that is used in electoral and legislative politics?"113. I do not pretend to explore such complex question here, but it helps me introduce the discussion on the sort of judicial majorities that are required within supreme/constitutional courts to declare as unconstitutional a statute approved by the legislature.

Linares differentiates between three regimes of required judicial majorities for the judicial annulment of legislation: (i) declaration of unconstitutionality by judicial unanimity, (ii) declaration of unconstitutionality by judicial supermajorities, (iii) declaration of unconstitutionality by judicial absolute majorities114. Just as with constitutional rigidity and constitutional amendment mechanisms, it is difficult to state which sort of arrangement can better promote the participatory potential of judicial review without further empirical research. It is possible to say, however, that the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review is better served under regimes of judicial unanimity and judicial supermajorities than under regimes of judicial absolute majorities.

Ferreres puts forth several arguments according to which statutes approved by legislatures should enjoy a prima facie presumption of constitutionality. Here, I focus on two: (i) an epistemic argument: constitutional judges should presume the validity of statutes since the solution given by democratic legislatures to the underlying conflicts of interests behind them is more likely to be correct than the solution that a supreme/constitutional court can arrive to115; and (ii) an equal political dignity argument: constitutional judges should presume the validity of legislation because if a democratically approved law is invalidated by the judiciary when the substantive problem is a controversial issue on which reasonable people can disagree, this constitutes an offense to the sense of the equal dignity of people116. According to this argument, constitutional judges should always presume the validity of legislation and only declare its unconstitutionality if powerful reasons trump this principle of in dubio pro legislatore.

If we want judicial review to genuinely operate as a "conversation initiator" that serves to trigger processes of mutual justification among citizens, we should avoid any institutional designs that may end up turning judicial review into an "expertocratic shortcut"117. For that, the prima facie presumption of the constitutionality of legislation must be respected, and the proper way to do that is by establishing rules that allow supreme/constitutional courts to exclude legislation of the juridical order, but only if such a decision is supported by a supermajority of justices, or by all of them. If we allow an absolute majority of justices to invalidate decisions made by democratic majorities in the legislature, judicial review will be fully vulnerable to the counter-majoritarian difficulty, and the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review will virtually disappear.

4.2.3. Rules of standing in supreme/constitutional courts

In her discussion with Waldron, Lafont argues that as long as the path to legal contestation is open to all citizens, there is no reason to accept the idea that judicial review disrespects political equality118. I have no objection to this argument, but the problem is that Lafont's case for judicial review seems to assume that it is indeed an open and accessible institution for the citizenry, something which needs to be empirically evaluated.

The rules of standing define who is entitled -and who is not- to trigger a process of abstract challenge against statutes before a supreme/constitutional court. Here, it is possible to differentiate between: (i) popular standing, where any person or citizen can initiate a process of judicial review; (ii) wide organic standing, where many sorts of institutions, such as political parties and public or private entities (such as NGO'S), have this possibility; (iii) narrow organic standing, which takes place when only political parties or institutions such as ombudsman offices can initiate the review process; and (iv) restricted standing, where only a specific percentage of legislators can trigger the process of judicial review119.

The participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review is strongest under regimes of popular standing, where the right to legal contestation is open to the citizenry in general, at least nominally. But as we move towards more restrictive rules of standing, the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review slowly fades away until its virtual disappearance under regimes of restricted standing. I should note that the formal opening of the constitutional court is not a sufficient criterion to determine whether the right to legal contestation is truly open to any citizen. Even constitutional tribunals with a regime of popular standing, such as the Colombian Constitutional Court, have been said to restrict access to the judiciary to elite sectors through the introduction of "argumentative burdens" imposed on the litigants that, in practice, exclude non-expert citizens120. That is, however, an empirical issue that goes beyond the reach of this paper.

4.2.4. The right to a voice: Who can intervene during processes of judicial review?

After a process of judicial review is initiated before a supreme/constitutional court, the right to a voice, that is, the right to intervene in debates regarding the constitutionality or unconstitutionality of the challenged statute can be legally distributed in different ways. Linares proposes the following categorization of the right to a voice: (i) very wide right to a voice, when any person or institution is entitled to intervene in the discussion through figures such as, for example, amicus curiae; (ii) moderately wide right to a voice, when the legislature or an official appointed by the legislature has the responsibility of defending the constitutionality of the statute before the supreme/constitutional court; and (iii) restricted right to a voice, when an official designated either by the judicial or the executive branch is the one responsible for the task of presenting arguments in favor of the constitutionality of the statute before the supreme/constitutional court121.

Similar to the case of the rules of standing before supreme/constitutional courts, the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review is strongest in polities with a very wide right to a voice, where the right to intervene in debates on the constitutionality is equally distributed among the citizenry. And as we move towards more restrictive distributions of the right to a voice, the participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review progressively vanishes away until its virtual disappearance in regimes with a restricted distribution of the right to a voice, where the branches with the weakest democratic credentials are the only ones entitled to exercise it. It is important to note that even in polities with a formally very wide right to a voice, the possibility to actually exercise it may be restricted to legal elites, so any firm conclusion on this matter requires more empirical research.

4.2.5. Selection rules for constitutional justices

It is possible to distinguish between three general selection rules for constitutional justices: (i) merit-based selection through competitive procedures, (ii) popular selection through elections, and (iii) political selection through representative institutions. In this last category, it is possible to differentiate between: (a) one-layered mechanisms, where one political organ selects the justices, and (b) two-layered mechanisms, where one institution nominates and another -usually the legislature- ratifies the justices122.

The participatory democratic legitimacy of judicial review seems to be at its strongest under political selection through representative institutions, and within that selection scheme, under two-layered mechanisms. At the risk of repeating myself, it is important to insist that the participatory understanding of judicial review is based on the idea that this institutional arrangement serves to enhance the communicative power of citizens who demand that their arguments regarding the constitutionality of a specific statute receive a proper hearing. Citizens are the senders of a message, and for that message to be rightly scrutinized it must reach an optimal receiver.

Merit-based constitutional judges may be very well suited to analyze the litigants' arguments, but they would easily be seen as depoliticized editorialists who enjoy their institutional position because of their epistemic superiority, not because of their status as equal citizens. Popularly elected judges will more easily be seen as equal citizens, but the popular election of constitutional tribunals may end up making their majorities and minorities too similar to those existing in the legislature, and this would make the contestatory nature of judicial review void. In contrast, in two-layered political selection mechanisms, the legislature is in charge of ratifying the nominees after a process of political deliberation and negotiation between representatives of different political parties and movements. In this sense, constitutional justices selected through two-layered political mechanisms are better suited to respect legislative decision making, while being willing to give appropriate scrutiny to the arguments posed by citizens who consider that the legislature has failed to track their interests and ideas in the process of public decision-making. This is contingent upon political realities, such as the distribution of seats in the legislature and the nature of the electoral system, but that is -yet again- an empirical issue that goes beyond the reach of this paper.