Introduction

The sailfin fishes are a group of catfish belonging to the Loricariidae family, morphologically characterized by possessing 10 or more dorsal-fin rays, not or diminutive interopercle that is on the hyomandibula when present, and a reduce the number of vertebrae between the dorsal fin and hypural (Armbruster, 1997; Armbruster, 2004; Armbruster & Page, 2006).

Pterygoplichthys genus is composed of 15 valid species endemic of the Neotropical region and distributed in diverse basins like Amazon, Magdalena-Cauca, Maracaibo, Panama, Orinoco, and São Francisco (Armbruster, 1997; Armbruster & Page, 2006). Seven species of the genus are registered to Colombia (Donascimiento et al., 2017): P. undecimalis (Steindachner, 1878) distributed in the Magdalena-Cauca basin and Lower Sinú (Eigenmann, 1922; Fowler, 1942; Miles, 1947; Dahl, 1971; Ortega-Lara et al., 2002; Maldonado-Ocampo et al., 2005), P. weberiArmbruster & Page 2006, Pterygoplichthys multiradiatus (Hancock, 1828), Pterygoplichthys lituratus (Kner, 1854), Pterygoplichthys gibbiceps (Kner, 1854), and P. pardalis (Castelnau 1855) report to Caquetá River and upper Amazon River drainages (Weber, 1992; Mojica et al., 2005, Bogotá-Gregory & Maldonado-Ocampo, 2006; Armbruster & Page, 2006; Buckup et al., 2007; Maldonado-Ocampo et al., 2008), and Pterygoplichthys zuliaensis Weber, 1991 distributed in the Caribbean region (Donascimiento et al., 2017).

Fish introduction processes are known from the middle ages but gained relevance during the end of the XX century. This activity was especially intense between 1950 and 1985, involving close 45 percent of 1354 introductions registered in different countries’ water bodies (Welcomme, 1988). History shows that translocation of living species by human action, whether deliberate or accidental, has been the most important cause of species’ natural distribution alteration since the Pleistocene era (Mooney & Cleland, 2001). Mankind migration history is key to understanding many of the oldest animal and plant population introductions. Currently monitoring border systems deficiency and lack of measures to prevent and control them -besides crescent processes of global economic interdependence, urbanization, agriculture development, and other ecosystem perturbation impacts- accelerate the species introduction process. Besides, it is expected that global climate change effects favor species invasion, exacerbating aquatic environments species introduction vulnerability (Dukes et al., 2009).

Pterygoplichthys genus has a history of introductions in many places and has a damaging reputation in countries where it has been introduced, such as Canada (Mendoza et al., 2009), United States (Florida, Hawaii, Nevada, Texas, California), Puerto Rico (Courtenay et al., 1984; Rodríguez-Barreras et al., 2020), Jamaica (Jones, 2008), Philippines (Chavez et al., 2006), Taiwan (Shih-Hsiung et al., 2005, Liang & Shieh, 2005), Singapore (Tan & Tan, 2003), Vietnam (Zworykin & Budaev, 2013), Serbia (Simonović et al., 2010), Costa Rica (Bussing, 2002), and Mexico, where the species are established in Balsas and Mezcala rivers in Michoacan state (CONABIO, 2004; IMAC, 2005; La Jornada, 2005), Amacuzac River, Morelos (Trujillo-Jiménez, 2003), and Catazajá and Medellín lagoons (Wakida-Kusunoki et al., 2007).

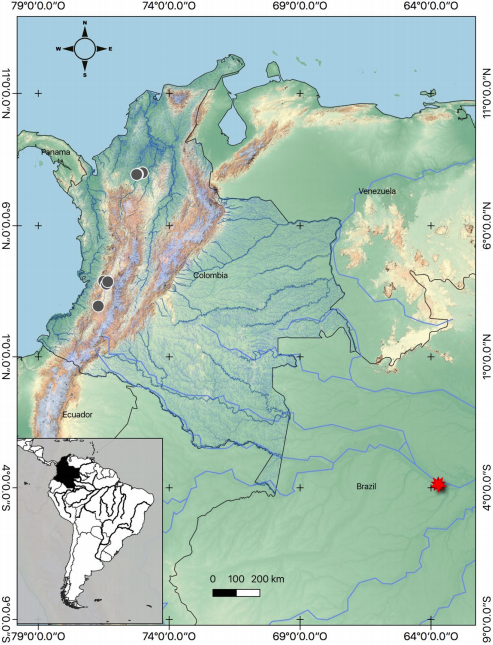

Until now, for freshwater fishes in Colombia, there are not reports for species of Pterygoplichthys genus outside their original distribution ranges (Galvis et al., 1997; Salinas-Coy & Agudelo-Córdoba, 2000; Ortega-Lara et al., 2006; Maldonado-Ocampo et al., 2005; Galvis et al., 2007; Maldonado-Ocampo et al., 2008). The aim of this paper is to determine the presence of a non-native species, Pterygoplichthys pardalis, through field samples in the Cauca river basin, as well as in the Salvajina and Calima dams (Figure 1), and the Patía river basin based in literature. Some taxonomic details were made, including comments of introduced species of the genus in the Cauca basin and feasible environmental disturbances are described.

Methodology

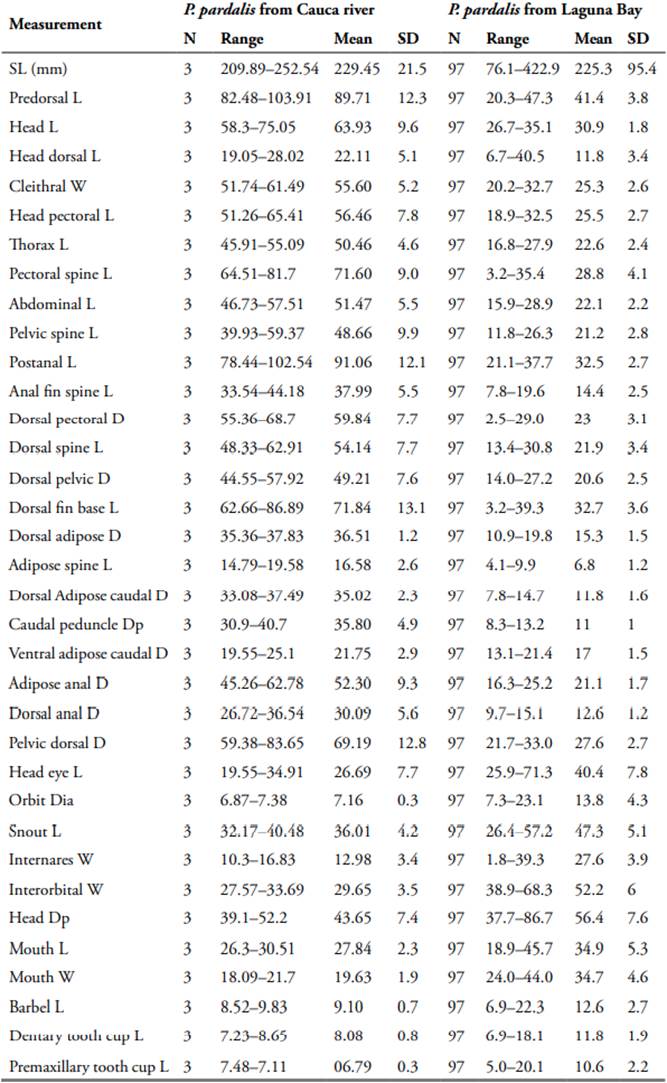

We examined material deposited in some collections such as the CIUA: Colección Ictiología Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Antioquia - Colombia, and CP-UCO: Colección Peces, Universidad Católica de Oriente, Rionegro, Antioquia - Colombia (Table 1). We evaluated 35 morphometric characters (Table 2) following Armbruster (2003a), Armbruster & Page (2006). Distances were measured in millimeters using dial calipers and then converted to ratios of standard or head length. Data collected were compared with available published and online Pterygoplichthys literature (Armbruster, 1997, 1998, 2002a, 2002b, 2003a, 2003b, 2004; Armbruster & Hardman, 1999; Armbruster & Page, 2006; Page, 1994; Weber 1992). Species nomenclature follows Armbruster (2003a, 2004).

Results and Discussion

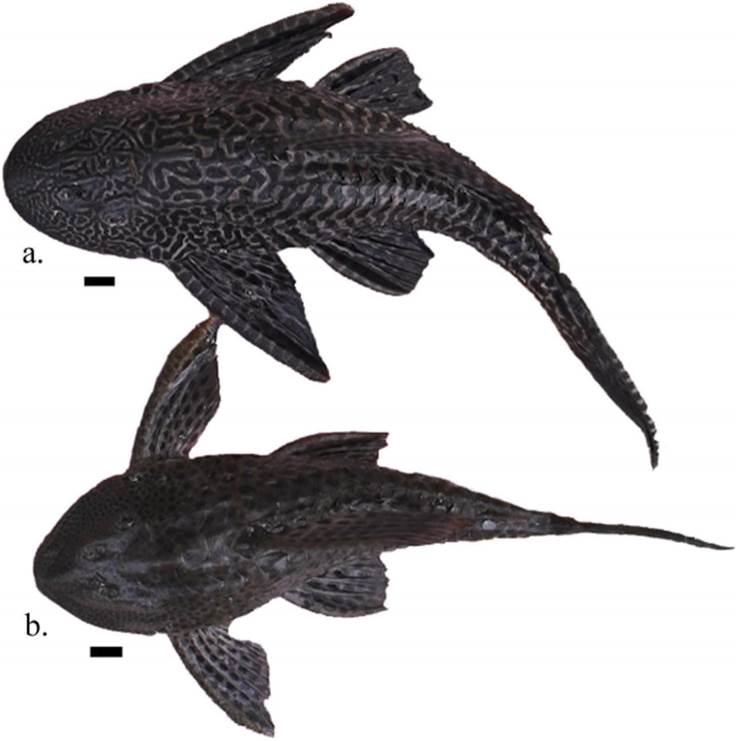

Pterygoplichthys undecimalis is the only valid species distributed in the MagdalenaCauca river basin according to Ortega-Lara et al., (2006), Maldonado-Ocampo et al., (2005, 2008), Lasso et al., (2011) and Donascimiento et al., (2017) (Figure 2b). Recently we captured one specimen of Pterygoplichthys pardalis (CP-UCO 1155) from the lower Cauca River basin, in Barrio Chino locality, a small town near Caucasia Municipality, in the Antioquia department (Figure 3). Additionally, we examined the material of this genus deposited in the CIUA collection from the upper Cauca river basin collected in La Vieja river (CIUA 429). We identify specimens belonging to P. pardalis that were misidentified as Hypostomus pardalis, indicating a species introduction in the Cauca river basin (from Salvajina dam to Nechí river) and in the Calima dam. Recently Moncayo-Fernández et al., (2017) indicated that P. undecimalis was transplanted in the Patía river basin. However, we suggested that this is a misidentification as it currently corresponds to a P. pardalis exemplar. A similar introduction has been previously reported for Loricariichthys brunneus (Hancock 1828) in the Cauca river basin (Ortega-Lara et al., 2006).

Figure 2 Specimens of non-native a) Pterygoplichthys pardalis and native b) P. undecimalis (in vivo) from Videles wetland in the upper Cauca river, Cauca Valley department. The bar represents one centimeter. Collected and photographed by N. Santos and P. Bonilla.

Figure 3 Pterygoplichthys pardalis (in vivo) from lower Cauca River. CP-UCO 1155. SL 191,48 mm. Collected and photo by M. A. Zuluaga.

Despite the Pterygoplichthys pardalis introduction evidence, there are no records of their introduction or transplantation in Colombia (Alvarado & Gutiérrez, 2002; Gutiérrez, 2006; Mancera-Rodríguez & Álvarez-León, 2008; Gutiérrez et al., 2012; Baptiste et al., 2010; Álvarez-León et al., 2002). In other places (such as USA, Puerto Rico or Mexico), there have been reported negative environmental impacts associated with P. pardalis introduction such as coastline instability, trophic chain alterations, commercial fisheries pressures (Amador Del Angel et al., 2014), and for other species of aquatic vertebrates, such as the manatee (Nico et al., 2009a), pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) (Bunkley-Williams et al., 1994), egg predation of other fishes (Chaichana & Jongphadungkiet, 2012).

Individuals found in this study have the typical mechanisms of all translocated or introduced populations studied in other countries (Leprieur et al., 2008), suggesting two possible mechanisms for their release: i) carelessness during the ornamental fishes trade, like, for example, when people released them into natural water bodies, due to specimens grow overpassing aquaria capacity or when people become bored with them (Mendoza et al., 2009), or by ii) aquaculture projects looking to “improve” region’s economy. For instance, it has been reported that the Calima dam population was moved by a fisherman (Figure 5), who introduce a few hundred specimens of P. pardalis from Sonso Lagoon in the Cauca river (near Buga municipality), where P. pardalis is wrongly sold as Merluza fillets (Brotula spp.) (COPESCAL, 1986; Fuller et al., 1999; Nico & Martin, 2001; Vidthayanon, 2005; Page & Robins, 2006; Nico et al., 2009b).

Figure 4 Pterygoplichthys pardalis from upper Cauca river. CIUA 429 (1-3). SL 209,89 mm. Collected by L. Ochoa-Orrego and A. Montoya-López. Photo by D. De Fex-Wolf.

Figure 5 Pterygoplihthys pardalis fishery in Calima dam with transplanted specimens from Sonso lagoon in the Cauca Valley department. Photo by N. Santos and P. Bonilla.

Species introduction is not a recent activity in the world. According to residents surveys, reports of Rivera et al., (2004), and photographic report dating since 1998, the introduction was made at least twenty years ago or more. Recently, in the Ibague fish market (Tolima department), we identified a significant number of P. pardalis for sale (Figure 6). The seller expressed that there is a great demand for this species and explained that the fish came from the upper Cauca River. Active trade of this species indicated that their introduction is not recent. This was also supported by Ortega-Lara (pers. comm.) in the Sonso Lagoon and Acevedo et al., (2010) in Videles wetlands, Calima and Salvajina dams (Figure 7). In the Ibague fish market is possible to observe sexually mature females specimens with eggs, probably indicating that species have active reproduction, where the high number of individuals offered for sale would be a result of a significant population.

Figure 6 Pterygoplihthys pardalis in Ibague fish market, Tolima Department. Note the quantity of fish including several females with eggs. Photo by L. Jara and O. Castillo.

Figure 7 Pterygoplihthys pardalis and Oreochromis niloticus fishery (both non-native species) in the Videles wetlands, Cauca Valley Department. Photo by N. Santos and P. Bonilla.

Observations presented here are based on photographs (Santos & Bonilla com. pers.) as, unfortunately, we do not obtain samples of Pterygoplichthys undecimalis (Figure 2). We use photographs to take measurements with ImageJ 1.43u for Mac (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). A comparison showed that P. pardalis has larger pectoral fins than P. undecimalis and the pectoral fins of P. pardalis reach and exceed more than half the length of the pelvic fins, but in P. undecimalis the pectorals fin reach the pelvic fin but do not extend for half of their length (Figure 4). Also, P. pardalis has a longer snout tip. The pelvic fins of P. undecimalis are longer than those of P. pardalis, and the first spine of the pectoral and pelvic fins in P. undecimalis is wider than in P. pardalis. The color pattern is also very different: P. pardalis has vermiculation on the body and first ray of the pectoral fin but P. undecimalis have circular spots (see Steindachner 1978: Table VIII). It is interesting to note that despite long time P. pardalis presence in the region and their high demand and consumption, this non-native species had not been correctly identified or declared as introduced by any corporation or research institute in the country.

An issue with the taxonomy of this genus refers to the diagnosed characters (Armbruster 2004). This is a disadvantage for species identification in the field, especially due to taxonomist specialized lack in these groups. Pterygoplichthys pardalis is still confused with our native species, P. undecimalis, as in some fishing identification manuals, (Rivera et al., 2004), field guides (Castaño, 2010), and the first catalog of inland fishery resources of Colombia (Carvajal-Quintero et al., 2010), or most recently, in Botero-Botero et al., (2019). To help separate them, we present some differences between these two species previously mentioned (see Figure 2).

Furthermore, when misidentifying Pterygoplichthys pardalis as P. undecimalis, some researchers and local fishermen usually confuse Pterygoplichthys with Hypostomus hondae or Hemiancistrus wilsoni; both species are widely found in the Magdalena-Cauca river basin. In some cases, P. pardalis has been called “the real Coroncoro” (el original Coroncoro). These taxonomic problems are so extensive that in La Pintada town (Antioquia department), some officials of regional autonomous corporations were fostering the species destruction, without a proper and clear determination of which morphotype or species needs to be eliminated, this led fishermen of the region to exterminate all species of loricariids present in their catches (Agudelo-Zamora pers. obs). To avoid this, we follow Weber (1992) and Armbruster (2002b) keys together with Loricariidae specialist confirmation. Due to these species have slight regional differences, these have been extensively hybridized (Sabaj-Pérez, 2011), and until now there is not a taxonomic revision of the genus to assist in the correct species identification. In this regard, Chavez et al., (2006) reported these small variations in meristic counts and morphometric measurements for the species, that we also found in our data.

In Colombia, ecosystem impacts caused by P. pardalis are not yet evaluated. Baptiste, et al., (2010) proposed guidelines for the categorization of all aquatic organisms introduced in the country. However, in other countries, some introduced species impact has been studied. One example of this was provided by Amador Del Angel et al., (2014:12), Hubilla et al., (2007), and Chaichana & Jongphadungkiet, (2012), who indicates that Pterygoplichthys has had negative impacts on freshwater biodiversity, causing higher water turbidity, consuming bivalves and gastropods and reducing others fishes amount. Also, Nico et al., (2009a) showed that Pterygoplichthys could cause damage to the manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) in Florida (more detail see Nico et al., 2009a), Yossa et al., (1998) and Samat et al., (2008) suggested that P. pardalis was more efficiently adapted to exploit benthic food resources than Prochilodus nigricans with a higher assimilation rate to convert food into biomass and thus growing faster.

There is an urgent need for a comprehensive study evaluating P. pardalis environmental impacts in Colombia. Leprieur et al., (2008) explained that about 20% of known extinctions are directly caused by invasive species. The anterior approach is highly relevant in Colombia several native species with similar food requirements are at risk (Yossa & Araujo-Lima, 1998), including P. undecimalis, Hypostomus hondae (Regan 1912), Panaque cochliodon (Steindachner 1879), Prochilodus magdalenae Steindachner 1879 and Ichthyoelephas longirostris (Steindachner 1879), which are important commercial fisheries species, as well as vulnerable species according to the Red Data Book (P. cochliodon and I. longirostris) (Maldonado-Ocampo et al., 2005; Mojica et al., 2012).

Author participation

HAZ conception, document write, individuals sampling and registration in CP-UCO, manuscript review, and final edition.

DDFW data collection and processing, photo registry contributions in the text, and final edition.

MAZ individuals collection, processing, and registration in CP-UCO, photographs and document contributions, and final edition.