Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura

Print version ISSN 0123-3432

Íkala vol.21 no.2 Medellín May/Aug. 2016

https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a02

EMPIRICAL STUDIES

DOI:10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a02

Linguistic Discrimination in an English Language Teaching Program: Voices of the Invisible Others

Discriminación lingüística en un programa de enseñanza de inglés: las voces de los otros invisibles

Discrimination linguistique dans un programme d'enseignement d'anglais : les voix des autres invisibles

Marlon Vanegas Rojas1, Juan José Fernández Restrepo2, Yurley Andrea González Zapata3, Giovany Jaramillo Rodríguez4, Luis Fernando Muñoz Cardona5, Cristian Martín Ríos Muñoz6

1 Universidad de Antioquia. Docente y coordinador del semillero de Investigación en Estudios Culturales, Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: vanegasmarlon@hotmail.com

2 Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: shakur841@msn.com

3 Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: andreita_3187@hotmail.com

4 Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: giojaramillo@yahoo.com

5 Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: luisfernando8920@hotmail.com

6 Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Mailing address: Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó. Transversal 51A #67B 90 Medellín, Colombia E-mail: crisman28@hotmail.com

Received: 2015-05-29 /Accepted: 2015-12-17

How to reference this article: Vanegas Rojas, M.; Fernández Restrepo, J. J.; González Zapata Y. A.; Jaramillo Rodríguez, G.; Muñoz Cardona, L. F.; Ríos Muñoz, C. M. (2016). Linguistic Discrimination in an English Language Teaching Program: Voices of the invisible others. íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 21(2), 133-151. DOI: 10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a02

Abstract

This descriptive research provides insight into how linguistic discrimination influences students' academic performance in the English teaching program at Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó in Medellin. Five groups were observed on four different occasions to accomplish the purpose of the study. Four professors and twelve students were interviewed to find out what attitudes and beliefs emerged inside the classroom. The analysis of data showed that standard language, native-speaker idealization, pressure from the professor, disesteem of one's own language-level, and discriminatory attitudes affected students' performance in aspects such as socio-affective factors, fear of negative evaluation, communication apprehension, devaluation of students' language variation, academic performance homogenization, mother-tongue restriction, extra visibility of high-proficiency students, discriminatory jokes, linguistic segregation, difficulty in interaction, and self-isolation. This study concluded that academic performance is affected by all types of discriminating attitudes, either in professors or classmates. Discriminatory attitudes trigger responses such as fear, segregation, anxiety, and apprehension, among others, thereby restraining and limiting class participation, quality of interaction, new concept and knowledge appropriation, motivation towards language, and course contents.

Keywords: linguistic academic performance, linguistic discrimination, positionality, socio-affective factors, standard language

Resumen

Esta es una investigación descriptiva acerca de cómo la discriminación lingüística interfiere en el desempeño académico de los estudiantes del programa de licenciatura en inglés de la Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó, de Medellín. Se observaron cinco grupos en cuatro momentos con el propósito de recolectar información relevante. Se entrevistaron cuatro profesores y doce estudiantes para determinar qué actitudes y creencias surgieron en el salón de clase. El análisis de los datos mostró que el lenguaje estándar, la idealización del hablante nativo, la presión del profesor y el menosprecio del propio nivel lingüístico afectan negativamente el desempeño de los estudiantes en aspectos como: factores socioafectivos, miedo a la evaluación negativa, aprehensión comunicativa, devaluación de las variaciones del lenguaje de los estudiantes, homogeneización del desempeño académico, restricción de la lengua materna, extravisibilidad de los estudiantes con alta suficiencia, actitudes discriminatorias, segregación lingüística, dificultad en la interacción y auto-aislamiento. Este estudio concluye que el desempeño académico se ve afectado por todo tipo de actitudes discriminatorias tanto por parte de los docentes como de los estudiantes. Dichas actitudes disparan reacciones como miedo, segregación, ansiedad y aprehensión, entre otras, que restringen y limitan las oportunidades de participación en clase, la calidad de la interacción, la apropiación de nuevos conceptos y la motivación hacia la lengua y los contenidos de los cursos.

Palabras clave: desempeño académico lingüístico, discriminación lingüística, posicionalidad, factores socio-afectivos, lenguaje estándar

Résumé

Cet article présente les résultats d'une recherche descriptive sur la manière dont la discrimination linguistique influence la performance académique des étudiants du programme de licence d'anglais à la Fondation Universitaire Luis Amigó de Medellín. Cinq groupes ont été observés à quatre moments, afin de collecter les informations les plus importantes. Quatre professeurs et 12 étudiants ont été interrogés afin de préciser les attitudes et les croyances apparaissant dans la salle de classe. L'analyse des données a montré que la langue standard, l'idéalisation d'un locuteur natif, la pression du professeur, le mépris du propre niveau de langue affectent négativement , les facteurs socioaffectifs, la peur de l'évaluation négative, l'appréhension communicative, la dévaluation des variations langagières des étudiants, l'homogénéisation de la performance académique, la restriction de la langue maternelle, l'extra visibilité des étudiants les plus compétents, les attitudes discriminatoires, la ségrégation linguistique, difficulté de l'interaction et auto-isolement des étudiants. De telles comportements produisent entre autres des réactions telles que la peur, la discrimination, l'anxiété et l'appréhension, qui restreignent et limitent les opportunités de participation en classe, la qualité de l'interaction, l'appropriation de nouveaux concepts et la motivation pour l'apprentissage de la langue et les contenus du cours.

Mots-clés: performance académique linguistique, discrimination linguistique, ségrégation linguistique, positionnalité, facteurs socio-affectifs, langue standard

Introduction

The communicative approach has been the most widely accepted and promoted methodology by the English language teaching community around the world, particularly in teaching and learning second and foreign languages. ''It has been treated as a discipline or as a neutral and objective technology that may be exported to any country'' (Lin, 2008, p. 15).

The communicative approach in language teaching has been mainly constructed in Western culture as a free-value technology and an effective learning approach. However, this teaching implicitly brings along with it values and ideologies such as individualism and utilitarianism. The kinds of interactions promoted in class cannot be accepted in certain traditional societies or cultural contexts (Ouyan, 2000, cited by Lin, 2008, p. 16).

In Colombia, English teaching through the communicative approach has been brought into question because of its neutrality. The discourse that portrays English as a neutral language envisions it as simply a means of communication. Guerrero and Quintero (2009) affirm that this perspective on language teaching arises from the idea that language is used to transmit a set of fixed rules. The idea is that language is not seen as a vehicle by which inequality, discrimination, sexism, racism, and power can be executed. They refer to the communicative approach as a prescriptive teaching method ''that presents a language which does not have real speakers and, therefore, no conflicts of any sort'' (pp. 138-139).

English language learning in our teaching program at Fundación Universitaria Luis Amigó (FUNLAM) is mainly characterized by the use of the communicative approach and task-based learning. Teachers usually organize their classes around content and form. Thus, class activities revolve around the study of grammar and pronunciation, the exploration of some themes, and the preparation of class projects, including oral presentations and group, project, and independent work.

Concerning English language learning in our program, we can say that our classes are characterized by the linguistic diversity found in every classroom. That is, classes are linguistically heterogeneous: there is mixed proficiency, meaning that we can find low, intermediate, and high linguistic proficiency students in the same class. We can even find native speakers of English, former immigrants who were raised in the United States and who are currently enrolled in the program.

As students enrolled in the program and members of the research group in Cultural Studies, we became highly sensitive to the kinds of interactions present in our English classes as a consequence of the linguistic diversity or mixed proficiency level classes as described above. Furthermore, our attention was drawn to the extra visibility given to high-proficiency (HP) students by professors in the program. Professors automatically tended to ignore low-proficiency (LP) students by sustaining long conversations with HP students and reducing opportunities for LP students to get involved in class discussions. We also observed that LP students remained quiet and ended up segregating themselves by forming groups with similarly performing classmates.

When students worked in groups, we had the opportunity to observe that, instead of cooperation, interaction among the groups was mediated by competition. Class activities usually prized and praised language-skillful students. Moreover, the same occurred when students gave oral presentations; LP students panicked and were apprehensive about speaking in public, while HP students performed successfully during class, thus gaining preferred attention from professors.

Considering that ''cultural studies seek to make an exploration of representations of and 'for' marginalized social groups and the need for cultural change'' (Baker, 2011, p. 5), this study arose from the need to give a voice to invisible students and deconstruct power relations at stake inside the English language classroom. ''Here, knowledge and language are never a neutral or objective phenomenon but a matter of positionality, that is, of the place from which one speaks, to whom, and for what purposes'' (Baker, 2011, p. 5).

On the other hand, the concept of social justice has also been considered in this study. This ''is a philosophy that extends beyond the protection of rights. Social justice advocates for the full participation of all people, as well as for their basic legal, civil, and human rights'' (Canada's Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 3). In our society, there are visible and invisible differences, but belonging to a society does not depend on backgrounds and particular circumstances; the idea is to address all kinds of oppression and recognize this diversity (Canada's Ministry of Education, 2008).

Linguistic human rights include the ''right to be recognized as a member of a language community; the right to interrelate and associate with other members of one's language community of origin; the right to maintain and develop one's own culture'' (UNESCO, 1996, p. 5). This claim becomes relevant as some students' linguistic rights were and are constantly trampled.

Democracy in the classroom is another significant concept to become acquainted with. This is a social process dependent upon three democratic dispositions: all citizens are moral equals capable of intelligent judgment and actions, focused on reflection, and with a need to decide on their own what to believe. Likewise, all citizens are able to work together on a day-to-day basis to settle conflicts and solve problems, McAninch's (as cited in MacMath, 2008, p. 3) affirms that we cannot talk about democracy in the classroom if only a few students take part in classroom activities and interactions.

Furthermore, according to Giroux, (1998) ''the term linguistic discrimination implies a concern in cultural studies for students as bearers of different social memories; as a consequence they are allowed the right to speak and to represent themselves in the pursuit of knowledge and selfdetermination'' (as cited in Sierra, 2003, p. 49). He also maintains that this illustrates a need for students to build their identity and find paths, which will allow them to respectfully have a meaningful and significant dialogue with others.

The above assumptions are further discussed and supported with theory in the following section. This will allow the reader to have a better understanding of our research project. Here we will show the specifics of the theory used as a basis for the study on linguistic discrimination. This study was framed along the lines of concepts and theories on linguistic discrimination, standard language ideology, native speaker idealization, accent, intelligibility, socio-affective factors, and linguistic diversity.

Theoretical Framework

Before discussing concepts and theories, it is important to clarify that linguistic discrimination has been studied and explored mainly in the workplace in bilingual or multilingual contexts. We found no evidence of studies carried out in the educational context, especially in (B.A.) teaching programs in Colombia. In studies that have explored linguistic discrimination or linguicism, the term linguistic discrimination is defined as ''ideologies and practices which are used to legitimate, regulate and reproduce an unequal division of power and resources defined on the basis of language'' (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1988, p. 13). Linguistic discrimination, therefore, can be seen as an imposition by entities or persons regarding language usage, which equates to a social division of power within a speech community.

In our research, the concept of standard language ideology comes to light through the definition of linguistic discrimination. Lippi-Green defines standard language as ''a bias toward an abstracted, idealized, homogeneous spoken language which is imposed from above, and which takes written language as its model. The most salient feature is the goal of suppression of variation of all kinds'' (1994, p. 166). According to Lippi-Green (1994), it should also be pointed out that powerful sociopolitical movements, such as the educational system, news media, the entertainment industry, and what is known as corporate America, have created and focused their efforts on establishing a standard language ideology (pp. 166-171). This ideology has permeated Colombia as English teaching curriculums, materials, and policies are influenced by foreign institutions that work to gain political and monetary benefits.

Moreover, if we look at the countries that spread these policies, a great number of people within their own communities don't speak a ''standard language'' since immigration and multiculturalism have influenced language over the last 100 years. Therefore, to emphasize standard language is to mislead and promote the idea of a single homogenous language, giving no recognition or importance to other speech communities that share the same language, although not the idealized version.

Standard language ideology emphasizes belief in an idealized version of the language, which in turn promotes a global perception of an idealized native speaker. The term ''native speaker'' suggests the existence of a single idealized register of the target language, despite the fact that there are many registers and styles within the same speech community. This language diversity is what makes the task of defining a native speaker difficult (Medgyes, 1992, p. 349).

In addition, Phillipson (1992) suggests that languages have several dialects, styles, and registers that make it difficult to define a native speaker. When one form of a language is preferred over others, this is due to social norms or standards and is not based on a linguistic criterion. Therefore, the concept of a native speaker is perceived as the belief that native speakers are the sole owners of language. Thus, the term ''native speaker'' in itself suggests the existence of a single kind of spoken English when there are actually many variations within a speech community. Similarly, English has become so globalized that no entity or person can claim ownership of the language. At present, individuals do not need to travel abroad to learn and become proficient in the language. This implies that the model of a native speaker is a fallacy.

Another dilemma that arises from the notion of a native speaker is the concept of accent:

An accent simply refers to one's way of speaking, the way one sounds when speaking, the way one uses phonological features such as stress, rhythm, tone and intonation. Contrary to popular belief, it is not just foreigners or immigrants who speak with an accent. Everybody speaks with an accent. Non-accent is nonexistent. (Kumaravadivelu, 2004, p. 1)

This is a general misconception of accent. Generally when people talk about accent, they are actually referring to the dialect a person has in a particular language, which is largely based on the region where the individual was brought up. Derwing and Munro (2009) state, ''accent has been blamed for all sorts of things. It has been seen as the cause of miscommunication and it has been used as a cover-up for racism and other kinds of discrimination'' (p. 476). Therefore, there is a need to understand and differentiate the notion of accent from that of intelligibility. The concept of intelligibility means being understood by an individual or a group of individuals at a specific time and in a specific context; we should all learn to speak a language in such a way that it is intelligible to others.

Intelligibility is assured through clear articulation and pronunciation, yet those who pronounce correctly and articulate clearly still speak with an accent (Kumaravadivelu, 2004, p. 2).

These subtle yet damaging forms of linguistic discrimination can lead to many socio-affective issues such as anxiety, lack of motivation, and a negative self-concept that can greatly affect the competence and performance students have regarding the target language and their interaction inside the classroom. Thomas Scovel views ''anxiety as a state of apprehension influenced by factors that are intrinsic and extrinsic to the foreign language learner'' (as cited in Fandiño, 2010, p. 149). A large number of students who have experienced linguistic discrimination due to their LP show a great deal of anxiety when compared to those with HP levels.

Such LP students experience a phase of communication apprehension, which, according to Scovel, is ''an uneasiness arising from the learner's inability to adequately express mature thoughts and ideas'' (as cited in Fandiño, 2010, p. 149), while Gardner and MacIntyre (1993) point out ''a fear or apprehension occurring when a learner is expected to perform in an L2 and he or she perceives an uncomfortable experience'' (p. 3). Another phase LP students go through is fear of negative evaluation by their peers and teachers, which Scovel describes as ''an apprehension arising from the learner's need to make a positive social impression on others'' (as cited in Fandiño, 2010, p. 150).

As a consequence, motivation in terms of attitude, desire, and effort is greatly affected. Peacock (1997) defines motivation as ''an interest in and enthusiasm for the materials used in the class, persistence with the learning task, and levels of concentration and enjoyment'' (p. 145), while Dornyei (1998) views it as ''extrinsic and intrinsic motivational factors related to the teacher, the course, and the group of language learners with which an individual interacts'' (p. 117). In this regard, it is important for teachers and EFL professors to differentiate between a student's performance and their competence.

Moreover, Freeman and Freeman (2001) state ''a speaker's competence in the language is defined based on what the students are able to do under the best conditions, while the performance may represent a kind of idealized ability'' (p. 55). Accordingly, our performance in the language does not always reflect our competence. In most EFL classroom situations, students may not perform up to their ability since they may be nervous, tired, bored, or anxious.

Language educators are encouraged to promote the concept of linguistic diversity in every aspect of their teaching. Educators recognize the linguistic diversity of students, who themselves have norms and values that they bring into the classroom. As such, teachers are encouraged to appreciate students' culture, beliefs, values, and norms in order to better understand the learner (Irving and Terry, 2010, p. 120).

Consequently, based on the literature explored and the issues that frame the problem statement of our study and its rationale, we have created a set of questions that helped us gain perspective and paved the way to set clear, reachable, and realistic objectives. The main question is stated as follows:

- How does linguistic discrimination influence students' academic performance in the English teaching program at FUNLAM?

- However, some other sub-questions emerged within the context of the inquiry process:

- How can language professors help LP students gain self-confidence and develop language accuracy?

- How can HP students help maintain a collaborative environment in class?

- How can a collaborative environment be encouraged in the language classroom?

Previous questions have led this study to describe how linguistic discrimination influences language learners' academic performance in the English Teaching Program at FUNLAM. Discriminatory attitudes influencing language learners' performance were defined and characterized. Finally, consequences of linguistic discrimination in the English language-teaching program at FUNLAM were also discussed.

Methodology

Given that our main objective was to describe how linguistic discrimination influences students' academic performance in the English teaching program at FUNLAM, this study followed a descriptive approach with a qualitative methodology. In this manner, Gamboa (2011, p. 7) notes that qualitative methods are used to explore human experiences. The data gathered from this type of research come from thorough analysis of a certain phenomenon with the purpose of describing it, giving it meaning, or identifying a process.

This paradigm is especially important since it is an opportunity to keep linguistic discrimination out of the classroom. Critical theory researchers look at their work as the first step towards political actions that lead to change regarding the injustices detected in society (Kincheloe and McLaren, as cited in Gamboa, 2011, p. 8). Additionally, critical theory aims to substitute dysfunctional power relations and their institutions for others that offer better opportunities to work in favor of the interests of society as a whole, as stated by Kincheloe and McLaren (as cited in Gamboa, 2011, p. 11), instead of promoting individualism and competition as characteristics of a society that privileged the interests of a minority.

This paradigm is especially important since it is an opportunity to keep linguistic discrimination out of the classroom. Critical theory researchers look at their work as the first step towards political actions that lead to change regarding the injustices detected in society (Kincheloe and McLaren, as cited in Gamboa, 2011, p. 8). Additionally, critical theory aims to substitute dysfunctional power relations and their institutions for others that offer better opportunities to work in favor of the interests of society as a whole, as stated by Kincheloe and McLaren (as cited in Gamboa, 2011, p. 11), instead of promoting individualism and competition as characteristics of a society that privileged the interests of a minority.

To contextualize the classroom environment that surrounded the participants in this study, it is relevant to refer to the objectives set for the courses observed. These were focused on the acquisition of the English language. That is, class activities were organized around the study of phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics of language. Other groups were designed to train teachers of English to children in language methodologies and learning material.

This study was carried out with a sample of 104 students and 5 professors for the observations. Of those 104, 16 students from LP level were selected for interviews, although only 12 of them were actually interviewed. All of them were members of the English Teaching Program at FUNLAM. Participants were students attending classes from the first to the tenth semester, both male and female learners between the ages of 20 to 35 with diverse linguistic levels.

With regards to the participating professors and their courses, the selection was made based on the availability of observers. In addition, these observations took place at unusual times of day (early in the morning and late in the evening) given that FUNLAM offers courses for students who work and study. These professors were both male and female between the ages of 40 and 50 years. All of them held bachelors and master's degrees in education and related areas. These participants also had several years of teaching experience in universities and were non-native speakers who learned English in Colombia, except for one professor who was a native speaker born and raised in the United States. A total of 5 professors were observed, and 4 of them were interviewed.

This study followed a qualitative research design. First, the literature on linguistic discrimination was examined to become familiar with previous studies on the topic. Second, class observations were scheduled based on observers' availability. Third, LP students were selected to be interviewed. Finally, the professors whose classes were observed were interviewed.

Observations were carried out to describe the quality of interactions fostered inside the classroom. Observers were invited to keep track of emerging attitudes in regards to the use of language in class. They were also expected to focus their attention on student-professor, professor-student, and student- student relations set within the class. The observation sessions were conducted for 5 weeks. Five observers visited 5 different courses, and a total of 21 classes were observed. Each observation lasted around 2 hours.

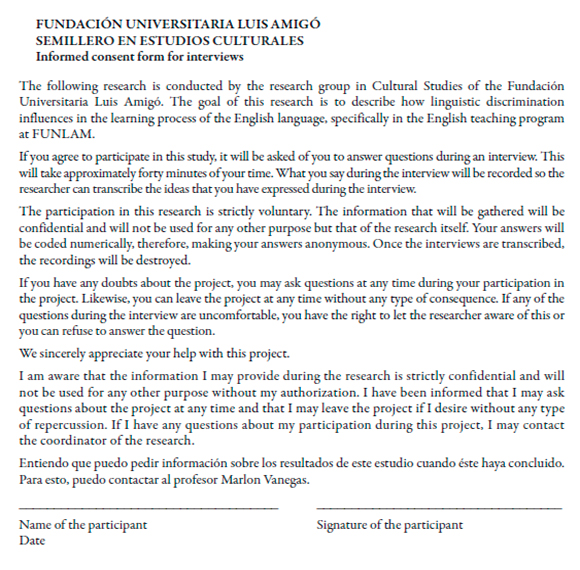

Selected participants who took part of this study, either to be observed or interviewed, were given an informed consent form to secure their permission to use the information provided for the development of the study. Implications, benefits and consequences of the data collection process were also explained. Consent forms were read aloud, and research ethics were explained in Spanish to avoid misunderstandings before conducting interviews and observations (see consent form of observations and interviews in appendix A).

This study used two instruments (journals and interviews) for collecting the data associated with linguistic discrimination and its influence on linguistic academic performance. Below is a list of the instruments used during the data collection process.

A triple entry format was designed to describe, reflect, and categorize information gathered from the observations (see journals form in appendix B). Observers wrote detailed descriptions of every action undertaken in class by students and professors. A total of 5 journals were written, and a total of 21 entries were registered. These journal entries were made over a period of 5 weeks and were kept by the research group.

Questionnaires for semi-structured interviews were designed to find out about the participants' perceptions and assumptions regarding discriminatory attitudes toward students in relation to their linguistic proficiency levels. All the interviews were conducted at the end of the observation process in a quiet environment. Participants' answers were audio recorded and their statements transcribed for further data analysis. Sixteen interviews lasting around 40 minutes were conducted —12 were conducted among students and 4 with the professors.

The student interviews were conducted in Spanish to elicit uninhibited answers. (See student interview form in appendix C).

Meanwhile, professor interviews were carried out to gain insights into the instructors' beliefs regarding the concerns of the study. In this particular case, all interviews were conducted in English. (See professor interview form in appendix C)

After all data was collected, the analysis was carried out considering the five steps proposed by Burns (1999), ''assembling data, coding data, comparing data, building interpretations, and reporting outcomes'' (pp. 157-160), as a guide for data analysis.

At the beginning of the study, the research group met twice a week for two months to re-read the transcriptions of the observations and the interviews, focusing on linguistic discrimination concepts and assumptions. During that process, some excerpts were highlighted, bringing about awareness of the research question and the objectives of the project. The highlighted passages were categorized.

Moreover, using a color coding system proposed by Arhar, Holly & Kasten (2001), the large number of categories that emerged from the 25 class observations and the 16 interviews (professors and students) were reduced to make categories more manageable. Initially, the observations were analyzed for the first outcomes. Then, we decided to create a chart to filter categories with the highest frequency of appearance. Subsequently, we reduced the categories to 16: 6 for student interviews, 5 for professor interviews and 5 for observations. Lastly, 6 categories arose based on the triangulation process mentioned.

Findings and discussion

Six categories were obtained from the data analysis process as follows: standard language idealization, native speaker idealization, professor pressure, disesteeming one's own language level, discriminatory attitudes, and linguistic segregation.

This is the establishment of what is considered to be the most acceptable variety of English language, promoted by the worldwide language teaching community. It refers to the language spoken by individuals with an extensive academic background who are themselves educators or broadcasters, who pay attention to speech, who are not careless in terms of grammar or pronunciation, and who agree with other individuals like themselves about what is proper in the language (Lippi-Green, 1997). This seems to be an important policy in the English language communities in Colombia as professors and future teachers are ingrained with these policies from the very onset of their undergraduate and graduate studies. Additionally, this ideology confirms that there are powerful organizations that establish standard English around the world. These organizations use the forms of spoken English from the United States and Great Britain as a reference for the blueprints in the teaching of English and its policies around the world. The following excerpts show how these policies have merged into factual beliefs based on this particular ideology.

- Professor 1: ''[It] is the, ah, the way people should speak the language in order to be understood by everybody in all different countries around the world'' (Professor interview excerpt, May 6th, 2014).

- Student 2: ''Since I was little I have always liked English; I have always dreamed of going to England or the United States, a country of English speakers, specifically those two which are the most known.'' (Student interview excerpt, May 8th, 2014)1

- ''The teacher corrected students' pronunciation and mistakes after reading the text; he just had students repeat the word as it should be pronounced'' (Y.A. González, Class observation #12, March 4th, 2014).

Standard language idealization caused some students to hesitate during the reading session and repeat words that they had pronounced correctly. Some students also seemed very cautions of making mistakes or expressed inability and frustration at not being able to pronounce correctly. Therefore, insisting on a standard form of English in the classroom can devalue other existing varieties of English. Furthermore, attempting to teach Standard English may promote discrimination in the language classroom based on a tendency to prefer native-like accents over nonnative accents, which can greatly affect learners' performance. According to Tollefson, discrimination based on accent can be considered a form of racism (as cited in Farrel and Martin, 2009, p. 3). Besides, many English speakers around the world use language based on the social group they are part of as an expression of their identity and their cultural values (Farrel and Martin, 2009, p. 4). This begs the question: why should a student be restricted in expressing him or herself in the manner in which he or she is most comfortable?

Native speaker idealization

This term comes from the idea that ''English is seen as the province of the idealized native speaker, something that he or she already possesses and that the outsider imperfectly aspires to'' (Leung, Harris and Rampton, 1997). Therefore, the belief of an idealized native speaker is ingrained on the premise that native speakers are the sole owners of language knowledge, which leads to the notion that people who are native to the language are the ones who have proper word usage and correct pronunciation, as can be seen in the following interview excerpt:

Professor 1: ''I try to use high-level students to give them feedback and help the others, especially in this career [program] because they are going to be teachers, so in that way they can improve their teaching skills. It happens in real life in every single class: you have different levels, so what we have to do is try to do our best at a time.'' (Professor interview excerpt, May 12th, 2014)

In this particular case, a student with a high proficiency level embodies the idealized version of the native speaker as the professor uses this person as the model to be followed in class. One of the negative influences the idealization of a native speaker has in the EFL classroom is the fact that professors tend to homogenize students' performance, underestimating individual differences in cultural background, education levels, learning styles, experiences, interests, and needs (Columbia University, n.p.). This kind of belief also tends to neglect the variety and regional expressions used across the territories of English speaking countries, in essence implying the existence of a single correct way of using the language, as is expressed in the following interview excerpt:

Student 1: ''Maybe in some other classes I have noticed that some teachers tend to prefer people with more perfect English, but I think the issue here is not that these people know more so let's work with them, but they are actually the ones who get the class moving.'' (Student interview excerpt, May 15th, 2014)2

From the analysis of this excerpt, it is evident that the student believes that HP students are those who contribute to the development of the class based on their linguistic proficiency. This was made evident during a group discussion in which a HP student was the most participative and asked most of the questions within the group of students: ''In this group, the student with the most proficiency in the language took the role of leader, as he was the one asking others what they thought'' (L.F. Muñoz, Class observation #5, March 6th, 2014).

Examining this belief in Kumaravadivelu's (2004, p. 2) language learning theory, we found there is a critical period during infancy in which the human brain and the phonological system are flexible enough to pick up the accent of the culture in which a person is immersed. Consequently, trying to make EFL students acquire the accent of a native speaker is a fallacy; this is particularly relevant as many students and professors seem to conflate the concept of accent with that of pronunciation. However, an individual who learns the English language in an EFL context will always be influenced by his or her mother tongue and culture. As Cook points out, ''It may be unrealistic to use a native speaker model for a language learner who can never become native speakers without being reborn'' (as cited in Farrell and Martin, 2009, p. 3). There are as many versions of English as users of the language are. Imposing an accent or presenting a model result in adopting a discriminatory attitude in the classroom.

There seems to be an attitude from professors to put pressure on students and force them to use English in the classroom without any regard for what students may feel or the angst that may arise due to the pressure to participate. These types of instructor attitudes greatly influence the class atmosphere, raising students' anxiety levels and making spontaneous participation more difficult. As mentioned in the literature review, anxiety can promote apprehension; specifically, this is called communication apprehension, which can be defined as an individual level of fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons. The issue of communication apprehension becomes increasingly important: ''General personality traits such as quietness, shyness, and reticence frequently precipitate communicative apprehension. When the ability and desire to participate in discussion are present, but the process of verbalizing is inhibited, shyness or reticence is occurring. The degree of shyness, or range of situations that it affects, varies greatly from individual to individual'' (Du, 2009, p. 163). Professor pressure also triggers LP students' fear of being negatively evaluated by the instructor and classmates. Such negative evaluation leads to unequal feedback from the professor and a discriminatory attitude from peers.

Furthermore, this type of negative evaluation causes problems in communication since interaction could potentially be altered. As one professor stated, ''The most important thing is that you have to push them as a teacher to use language; no matter if they don't want to do it, they will improve little by little'' (Professor interview excerpt, May 16th, 2014). This was also evident in class observations:

The professor says to talk about the focal point of the topic; well, she [the professor] starts to get annoyed because she doesn't hear what she wants to hear. She always points at the person she wants to hear the answer from. (C.M. Ríos, Class observation #19, March 10th, 2014).3

Situations such as the class observation mentioned above are intimidating for many students with low proficiency. This can lead to moments of anxiety, apprehension, and frustration with the language. It therefore implies a relatively tense atmosphere arising from pressure exerted by the professor and public error correction, which in turn greatly impacts students' affective filter. Moreover, these situations can lead LP students to leave the English teaching program.

Disesteeming one's own language level

The concept of disesteeming one's own language level becomes evident when LP students underestimate themselves when compared to their intermediate and HP-level counterparts, thus leading to high levels of anxiety in students with low language proficiency. As one student put it:

I get very anxious, it makes me feel very nervous, and then what happens? There is a negative impact of nerves and anxiety: which one is it? Maybe I am affected in the sense that I pronounce incorrectly, I forget what I have to say, what I have to do; I get blocked. Yes, there are cases in which you study, and, well, you are sure of things, but you don't do well because the class is very advanced. (Student interview excerpt, May 19th, 2014)4

Another student shared a similar experience: ''when you meet people who know a lot and who speak so well, you think: 'hmm! They know more than I do' and you feel like intimidated'' (Student interview excerpt, May 21st, 2014).5 In these particular cases, students feel apprehension, anxiety and intimidation arising from a lack of fluency. Consequently, this leads to many low-proficiency students realizing they will not be able to achieve the course objectives, causing some of them to drop out. There is a tendency in many students from the English teaching program to believe that accent and its neutralization will allow them to be accepted inside the community of learners when the real focus should be on intelligibility in the language.

Discriminatory attitudes

Akar-Vural and Gömleksiz (2010) suggest that discriminatory attitudes are tendencies to look down upon and exclude those who are not considered part of a predominant group. These excluding behaviors were identified during 5 out of 21 class observations when professors restricted L1 usage and gave extra visibility to HP students by overlooking and underestimating LP students, as can be gleaned from the following class observation notes:

A student went to the board to complete an exercise, which the student didn't do correctly; the professor told the student to sit down without providing any positive or negative feedback. On the other hand, a student with an intermediate level correctly finished the exercise, and the professor positively complimented the student. (G.J. Rodríguez, Class observation #21, March 13th, 2014)

Additionally, HP students used sarcasm, teasing and scorn when LP students made grammatical mistakes as they spoke or incorrectly pronounced a word. This was observed during 13 out of 21 class visits.

All of this is referred to the unfair treatment given by individuals based on prejudices and stereotypes. For example, ''The student of American origin made a joke when a classmate read a sentence; the rest of the group laughed while the student didn't say anything and just looked down. (G.J. Rodríguez, Class observation #21, March 14th, 2014). A similar situation arose when ''A student who was raised in the United States corrected a classmate, basically pointing out that the word 'comfortable' was not pronounced correctly and making a gesture of disapproval'' (L.F. Muñoz, Class observation # 21, March 17th, 2014). According to a student, ''sometimes you feel fear in a particular class because they make fun of you or you always find the ones who are talking with each other that are making fun of you'' (Student interview excerpt, May 22nd, 2014).6 In a teacher's words, ''So for me, I don't agree to use that language, I try not to allow my students to use Spanish in the class even when they are speaking among them'' (Professor interview excerpt, May 20th, 2014). Based on the previous statements, it can be asserted that the quality of interaction between students is affected by diverse linguistic levels. This becomes very unfortunate when LP students cannot take advantage of their higher-level counterparts' linguistic prowess; on the contrary, these LP students are negatively judged and mocked by their peers. Thus, the gap between low- and high-proficiency learners is increasing on a day-to-day basis due to the discriminatory attitudes many students have.

Concurrently, this category has a major impact on the academic performance of students as a result of being judged and scrutinized by classmates, which leads to frustration and disgruntlement regarding the English teaching program. Some students who were observed during the classes expressed a fear of making mistakes in front of their peers, prompting LP students to experience strong feelings of insecurity during class interactions, presentations, and exams.

Linguistic segregation

This term refers to an intentional attitude of linguistic exclusion inside the classroom. The observations showed that students created an unequal distribution among themselves based on their linguistic proficiency. Likewise, professors allowed students to pick their groups without taking into consideration the consequence this might have on LP students. In the words of a student, ''Yes, that's true, they look for each other. The ones who have the best linguistic ability partner up with each other, and the ones with lower linguistic levels are left out of those groups'' (Student interview excerpt, May 26th, 2014).7 According to a professor, ''Normally, my classes are divided in groups and normally I'm not in charge of dividing the groups. I just tell them that I need to organize groups of three or four people and they organize the groups'' (Professor interview excerpt, May 27th, 2014). Although this may seem like a very democratic way of dividing the class, the tendency observed during the classes was that students with the same proficiency levels would stick together and form groups based on proficiency.

Moreover, these situations have some consequences, including decreased motivation among LP students since they are not active participants in classroom activities due to their language level. A subsequent consequence that arises from a lack of motivation is that learners avoid taking risks and prefer working alone during classroom activities. In essence, these LP students become self-isolated and do not take part in class interactions. Thus, linguistic segregation can have great repercussions on immersion in the English classroom. What possibility of immersion exists if interaction is influenced by segregation?

Conclusions

Drawing on the triangulation and interpretation of data sources, this study described how linguistic discrimination influence language learners' academic performance in the English teaching program at FUNLAM. We conclude that academic performance is affected by all types of discriminatory attitudes, either by professors or classmates. LP students are the most socio-affectively influenced, especially those students who are still part of the original program known as Licenciatura en Educación Básica con énfasis en Inglés (Basic Education Program with an Emphasis on English). Discriminatory attitudes trigger responses such as fear, segregation, anxiety, and apprehension, among others. This restrains and limits class participation, quality of interaction, new concept and knowledge appropriation, and motivation towards the language and the course.

The discriminatory attitudes that most affect the academic performance in the teaching program are:

- Mockery of LP students: HP students mocked and judged the way LP students pronounced, spoke, and expressed themselves.

- Persistent correction from professors and classmates: Professors and classmates corrected LP students, insisting on a ''proper way'' of using the language.

- Native speaker idealization: This is the belief that ''native speakers'' own language knowledge and thereby serve as the reference for achieving appropriate language command and measuring all attempts of practice in the English language class.

- Standard language ideology: This is the ingrained belief that there is only one correct form of English, which is established by sociopolitical powers; thus, it is adopted and believed as true by many foreign-language professors.

- Professor pressure to make students participate: Professors' insistence on participation increased anxiety levels, sometimes making students feel intimidated (to a point where learners limit their chances to interact with the target language). Pressure exerted by professors reduced willingness to participate, usually making students become unmotivated and sometimes provoking students to drop out.

- Negative peer comparison: Students tended to compare their linguistic levels, leading to a low self-concept based on their linguistic proficiency and situations triggered by the professor. LP students tended to feel emotionally intimidated by their HP peers.

- Stratification of the language (grouping criteria): Learners group themselves in relation to their linguistic proficiency levels, shielding this tendency with a relationship of friendship and interfering with the quality of interaction between the students in a class.

- Belief in an idealized accent/dialect: This refers to the generalized perception that American and British accents are the only ones that may validly be taught and expressed. There is a perception that some accents are more legitimate than others.

- Invisibility by peers and teachers: LP students were often ignored by classmates and professors who did not consider them active elements in the development of the class (insufficient oral production). HP students tended to overlook LP students by segregating or disregarding them based on their language level.

Recommendations

Considering the results of the study, we as a research group would suggest three recommendations for the English teaching program in order to examine discriminatory attitudes to promote social justice, democracy, and equality in the classroom.

First, we invite professors to reflect upon the way communication develops in the classroom in order to balance the affective filter and develop spaces for language interaction. It is crucial to stress that professors and individuals who have a high proficiency acknowledge the potential many LP students may have. Additionally, we invite professors to comprehend how cultural and social knowledge enter into language interaction based on the fact that language educators should promote the concept of linguistic diversity in every aspect of their teaching.

We also suggest that the English teaching program at FUNLAM should make a conscious effort to understand student background, culture, and life experiences in order to promote a more diverse classroom. In addition, students are invited to interact and avoid self-isolation and feel free to participate regardless of their linguistic level.

For further research projects, and based on the reflections done throughout this study, we suggest exploring issues that continue to promote social justice and democracy in the classroom. Issues such as cultural factors and academic performance, gender discrimination in the language classroom, language cultural identity, the construction of subjectivities in the language classroom, and how culture influences cognitive development are future concepts the research group would like to explore in depth.

Notas

1 Excerpt translated into English.

2 Excerpt translated into English.

3 Excerpt translated into English.

4 Excerpt translated into English.

5 Excerpt translated into English.

6 Excerpt translated into English.

7 Excerpt translated into English.

References

Adreou, G. & Galantomus, I. (2009). The native speaker ideal in foreign language teaching. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(2), 200-208. [ Links ]

Akar-Vural, R., & Gömleksiz, M. (2010). Us and others: a study on prospective classroom teachers' discriminatory attitudes. Egitim Arastirmalari-Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 38, 216-233. [ Links ]

Aravena, M.; Kimelman, E.; Micheli, B.; Torrealba, R. & Zúñiga, J. (2006). Investigación Educativa I. University of Arcis, Chile. Retrieved from http://jrvargas. files.wordpress.com/2009/11/investigacion-educativa. pdf [ Links ]

Arhar, J., Holly, M. & Kasten, W. (2001). Action Research for Teachers: Travelling the Yellow Brick Road. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. [ Links ]

Barker, C. (2011). An introduction to cultural studies. In Willis, P. Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publications. Retrieved from: http://uk.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/ upm-binaries/66910_An_Introduction_to_Cultural_ Studies.pdf [ Links ]

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative Action Research for English Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Canada's Ministry of Education (2008). Making Space. Teaching for Diversity and Social Justice throughout the K-12 Curriculum (pp. 1-18). Canada: GT Publishing Services. [ Links ]

Columbia University (n.d). Respecting individual difference. [PDF document] Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. New York, NY. Retrieved from http:// www.columbia.edu/cu/tat/pdfs/indiv_difference.pdf [ Links ]

Derwing, T. & Munro, M. (2009). Putting accent in its place: Rethinking obstacles to communication. Lang. Teach., 42(4), 476-490. [ Links ]

Dornyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31, 117-135. Retrieved from http://web.iaincirebon.ac.id/ebook/indrya/Motivation/1998-dornyei-lt.pdf [ Links ]

Du, X., (2009). The affective filter in second language teaching. Asian Social Science, 5(8), 162-165. Retrieved from http://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ass/ article/download/3429/3106 [ Links ]

Fandiño, Y. (2010). Explicit teaching of socio-affective language learning strategies of beginner EFL students. íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura. 15(24), 148-151. [ Links ]

Farrel, T. & Martin S. (2009). To teach standard English or world Englishes? A balanced approach to instruction. English Teaching Forum, 2, 2-7. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ923448.pdf [ Links ]

François, Grin. (2005). Linguistic human rights as a source of policy guidelines: A critical assessment. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 9(3), 448-460. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. & Freeman, Y. (2001). Between Worlds: Access to second language acquisition. Porstmouth, NH: Heinemann. [ Links ]

Gamboa, R. (2011). El papel de la teoría crítica en la investigación educativa y cualitativa. Revista Electrónica Diálogos Educativos, 21. Retrieved from dialnet. unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3931278.pdf [ Links ]

Gardner, R.C. & Macintyre, P.D. (1993). A student's contributions to second-language learning: Part II. Affective variables. Language Teaching, 26, 1-11. Retrieved from https://www.academia. edu/5348479/A_students_contributions_to_second_ language_learning._Part_II_Affective_variables [ Links ]

Guerrero, C. & Quintero, A. (2009). English as a Neutral Language in the Colombian National Standards: A Constituent of Dominance in English Language Education. Profile, 11(2), 135-150. [ Links ]

Irving, M. & Terry N. P. (2010). Cultural and linguistic diversity: Issues in education. In Colarusso, R. & O'Rourke. Special Education for all teachers (pp. 109-132) (5th. ed.). Georgia State University, GA: Kendall Hunt. [ Links ]

Kincheloe, J. & McLaren, P. (2005). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 303-342) (3rd. ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2004). Accent without attitude. Multicultural Forum, 15(1), 1-3. Retrieved from: http:// www.bkumaravadivelu.com/oped%20pdfs/Accent%20without%20attitude.pdf [ Links ]

Leung, C. Harris, R. & Rampton, B. (1997). The idealised native speaker. Reified ethnicities, and classroom realities. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 543-560. [ Links ]

Lin, Angel Mei Yin (2008, May-August). ''Cambios de paradigma en la enseñanza del inglés como lengua extranjera: el cambio crítico y más allá,'' Revista Educación y Pedagogía. Medellín, Universidad de Antioquia, Facultad de Educación, 20(51), 11-23. [ Links ]

Lippi-Green, R. (1994). Accent, standard language ideology, and discrimination pretext in the courts. Language in Society, 23, 163-198. [ Links ]

Lippi-Green, R. (1997). English with an accent: Language, ideology, and discrimination in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge. Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/.../02e7e52a962a7d7941000000. [ Links ]

McAninch, A. (1999). More or less acceptable case analyses: A pragmatist approach. In R. F. McNergney, E. R. Ducharme, & M. K. Ducharme (Eds.), Educating for Democracy: Case-method Teaching and Learning. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

MacMath, S. (2008). Implementing a democratic pedagogy in the classroom: putting Dewey into practice. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education, 1, 1-12. Retrieved from http://www.cjnse-rcjce.ca/ojs2/index.php/cjnse/article/view/16/13 [ Links ]

Medgyes, P. (1992). Native or non-native: Who's worth more? ELT Journal, 46(4), 349. [ Links ]

Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic materials on the motivation of EFL learners. English Language Teaching Journal, 51(2), 144-156. Retrieved from http://203.72.145.166/ELT/files/51-2-6.pdf [ Links ]

Phillipson, R. (1992). ELT: the native speaker's burden? ELT Journal, 46(1), 11-19. [ Links ]

Sierra, Z. (2003). Diversidad cultural: desafío a la pedagogía. Desafíos, 9, 38-70. [ Links ]

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. and Phillipson, R. (1994). Linguistic Human Rights: Overcoming Linguistic Discrimination. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [ Links ]

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (1988). Multilingualism and the education of minority children (pp. 9-44). In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.), Minority Education: From Shame to Struggle. Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters. [ Links ]

UNESCO. (1996). Universal Declaration on Human Rights. World Conference on Linguistic Rights. Barcelona, Spain: UNESCO. [ Links ]