Introduction

It is true that "[t]he topic of literacy is never far from the concerns of educationalists, politicians and the media" (Aikman, Maddox, Rao & Robinson-Pant, 2011, p. 577). Since the UN included literacy in its Millennium Development Goals, the importance of literacy has secured its place in the collective consciousness as a central marker of development. UNESCO claims that "[l]iteracy is a fundamental human right and the foundation for lifelong learning. It is fully essential to social and human development in its ability to transform lives" (UNESCO - Literacy); the assertion that literacy is a fundamental human right sets literacy in the context of 'linguistic human rights' (see Skutnabb- Kangas, 2000, ch. 7) and allows for meaningful connections to be drawn between literacy and indigenous rights as proposed by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007. Of particular interest in the UN declaration is article 13: "[i]ndigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures" (2007, p. 8). Understanding article 13 raises, amongst others, the question of what 'their' writ- ing systems and 'their' literatures are; the question of 'indigenous literacy' is therefore a current and important one that merits discussion. As both 'literacy' and 'ingeniousness' are complex terms, each deserves some brief consideration here in order to better understand the ensuing discussion.

Literacy. What is understood by 'literacy' has evolved over time; literacy is often framed as an object that a person has. Notions that "[t]he European conquerors brought with them not only Spanish and Portuguese but also literacy" (Hornberger, 1992, p. 191) are pervasive, and reflect a linking of the arrival of the European alphabetic writing tradition and the dawn of 'literacy' in Latin America. Literacy then is represented in the Western imaginary as synonymous with having an alphabetic writing system. In light of poststructuralist thinking and the increasing focus on individual praxis in the social sciences, literacy becomes not just about 'having ,' but about 'using ,' and as such can be considered as 'social practice' (Gee, 2011, p. 76ff.; Street, 2009, p. 21). A 'social literacy' framework focuses on the fact that "literacy is always embedded within social institutions and, as such, is only knowable as it is defined and practiced by social groups" (Purcell-Gates, 2007, p. 3). Such an approach therefore affords insightful discussion of literacies in their ethnographic settings and allows consideration of the extent to which the practices in which these literacies are embedded can be considered 'indigenous.'

Indigenousness. The notion of 'indigenous literacy' is problematic in that it relies on 'indigenous' as an essentialist social category.

Taking its etymological roots, the word simply means one who is native to a region (OED s.v. 'indigenous'), and as such in a Latin American context it is used to distinguish between the 'settlers' and 'natives.' As a category term often imposed on people from the outside, however, 'indigenous' comes with hegemonic expectations of social behavior, and therefore behavior that does not fit with these expectations is seen as transgressive (see, for example, Graham, 2002). In light of social constructionist theories in which "identity is achieved by a subtle interweaving of many different threads" (Burr, 2003, p. 106), essentialist categories break down and as such 'indigenousness' can be understood as one of these 'threads' available to individuals for 'identity work.'

Indigenousness then is "highly contextual" (Canessa, 2006, p. 244) and often relies on fulfilling expectations or drawing 'in-' and

'out-group' boundaries through interactive positioning (De la Cadena, 2000). In being reclaimed as an 'ingroup' identity marker, 'indigenous' has gained a politicized element and is often evoked or rejected for political reasons1. 'Indigenousness' is constructed by means of alignment to different cultural symbols (for example language, clothing, place of birth, occupation, beliefs, etc.) which are community-specific (King, 2000, p. 26). Given the previous discussion of 'social literacy', we will see that literacy can be considered 'indigenous' when the practice is aligned with these 'cultural symbols.' 'Indigenous literacy' then, is not just the 'writing down of indigenous languages,' but how literary practice is enacted in specific communities.

Proposal. This paper uses as a starting point the UNESCO and UN declarations and aims to explore the concept of 'indigenous literacy' in Latin America with specific reference to the Quechua-speaking Andean region. It ought to be noted that the aim of this paper is not to 'speak for' indigenous peoples in defining 'their' literacy, but rather to highlight some of the problems involved in defining 'indigenous literacy' and avoid an overly-simplistic reading of the UNESCO and UN declarations.

The second section of this paper considers literary practice in the colonial period: it will be seen that both the technolog y introduced (the European alphabetic script) and the form this took (the book) circumscribed pre-Columbian literary practice. The third section is concerned with the how the technolog y introduced continues to affect lit- eracy practices in the Quechua-speaking Andean region as will be shown through the debate surrounding the standardization of the Quechua alphabet. Finally, the fourth section considers a 'social literacy' orientation, illustrating how such an approach can bring us closer to defining 'indigenous literacy practice.'

Colonial Literacy

This section considers the literary technolog y and form brought to Latin America as a result of the Spanish conquest and the ideologies that came with them. I use the term 'technolog y,' employed by Sampson (1985, p. 8), to highlight the fact that alphabetic literacy is something people use; it is not simply the technolog y itself, but also its use that will be of interest in this paper. The distinction between 'technolog y' and 'use' is comparable to a distinction to be made between 'technolog y' and 'form' (discussed below): I understand 'technolog y' to be the alphabetic writing systems themselves; I understand 'form' as the channel through which literary practice takes place. In the fifteenth-century European context, this was primarily the book (Mignolo, 1994, pp. 20ff.). The distinction between 'technolog y' and 'form' is perhaps not entirely satisfactory, but ser ves as a useful heuristic tool in understanding 'literacy' in the colonial era.

Technology. 'Writing' and 'literacy' in a European context are often seen as the pinnacle of linguis- tic achievements ( Joseph & Taylor, 1990, p. 5), the end product of an evolutionary process whereby European alphabetic systems are seen as the only 'true' writing systems that ''develop gradually from a cruder use of mere memory aides'' (Ong , 1982, p. 85). This evolutionary model of writing imposes a structuralist divide between 'literate' and 'illiterate' or, more accurately, 'pre-literate' peoples. At its most extreme, non-alphabetic writing is seen as a barrier to higher cognitive abilities; it is held by some that with the advent of alphabetic literacy,

no longer did the problem of memory storage dominate man's intellectual life; the human mind was freed to study static 'text' ... a process that enabled man to stand back from his creation and examine it in a more abstract, generalised, and 'rational' way' (Goody, 1977, p. 37; cf. Ong , 1982, p. 24).

In the evolutionary model then, the very existence of alphabetic literacy improves cognitive abilities.

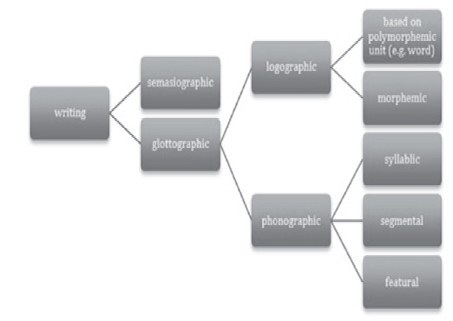

Elizabeth Hill-Boone is among those who dismiss the evolutionary model. Evoking Sampson's topol- og y (see figure 1), she illustrates that in Western ideologies, writing is often tantamount to making speech visible (i.e. using glottographic and, most commonly, phonographic systems) and argues that the inclusion of semasiographic systems, in which writing is no way related to speech, but directly to 'meaning,' in a topolog y of writing allows for a clearer understanding of pre-Columbian literary technologies (Hill-Boone, 1996, p. 14ff.).

Figure 1 A topology of writing systems (Sampson, 1985, p. 32)

The narrow vision of what 'writing' was led to the encoding of indigenous languages in Roman script in an attempt to 'render the spoken visible.' Latin was seen by those chronicling the 'New World languages' as a universal linguistic system, and as such this was taken as the grammatical basis for the Amerindian languages (Mignolo, 1992, p. 304). Since they were Spanish speakers, the early scholars' attempts to represent the sounds of the languages were governed by Spanish phonographic rules (the lasting effect of which will be discussed in the third section of this article). The first 'alphabetizing' of indigenous languages, then, can be understood as an ''opression symbolique'' (Calvet, 1999, p. 233), a 'symbolic oppression' whereby languages are forced into the norms of an external system and made an object which the colonizers can 'possess' (Mignolo, 1992, p. 306). From the outset, the 'technolog y of literacy' was used in such a way that it removed language and literacy from the indigenous peoples and reframed them to fit with a colonial worldview.

Form. The form of the book had tremendous symbolic importance in Europe, especially in the context of the Spanish colonization of the 'New World'. The colonizers, being contracted to the Catholic monarchy, were effectively working under the auspices of the Catholic Church (Truxillo, 2001, p. 73). As such, I suggest that their actions gained legitimization and authority from the Bible, the prototypical book. The 'book,' then, is seen as an authoritative entity and therefore the only way in which legitimate literary practice can be enacted. This position is illustrated in the burning of the Mesoamerican codices (religious texts) in the belief that they were dictated by the devil (Mignolo, 1992, p. 317). Although the 'words' in the books held no meaning for the colonizers, the authority of the object which they recognized as 'book' did, and as this authority challenged the religion they had come to promulgate, the codices were destroyed.

The other side of this ideolog y of the book is highlighted in the mythicized story of 'Atahuallpa and the Bible.' According to the story, the Inka Atahuallpa was handed a Bible by the Spanish Friar Vicente, but the Inka's inability to understand the authority of the Bible led him to dismiss it and throw it down, which was understood by the colonizers as the Inka's dismissal of Catholic doctrine (for a full account, see Guamán-Poma de Ayala, 1613, pp. 109-110). Given that before he was passed the book,

Atahuallpa and Friar Vicente had been speaking through a translator, the Friar cannot have expected Atahuallpa to understand the language inside; he must have expected the Inka to recognize the authority that comes from the very fact of the object's being a book. The colonial idea of literacy-as-book meant that 'non-book' literacy practices were not acknowledged as such, a kind of violence by omission.

Perhaps the most striking example of this omission is that of the Quechua khipu from colonial conceptions of literacy. The khipu are knotted-cord systems that "abstract information through color, texture, form and size (of the knots and the cords), and relative placement, but they do not picture things or ideas" (Hill-Boone, 1996, pp. 21-22). The khipu, therefore, is a semasiographic system (see above). In light of the ideolog y of the book, it was believed that the khipu was merely a tool for encoding statistical data based on mathematical logarithms (Locke, 1912). Whilst this assertion attests to the 'technolog y' of the khipu, the form it takes seems to preclude its being considered as 'literacy'(Mignolo, 1994, p. 237). Modern-day scholars argue that it is most likely that the khipu knots did not just encode statistical data but served a mnemonic function whereby hose who knew how to'read' the knots, the khipu kamayuq, would use them as a basis for elaborating a range of literary functions (Salomon, 2004, pp. 6-7). Early indigenous literary practice, then, was omitted from the European paradigm imposed at the point of colonization as it was contrary to European literary ideologies.

Indigenismo. In the early twentieth century, 'indigenous' became a marker of in-group identity with the rise of indigenismo, a literary-cultural movement especially prevalent in Peru. It could be assumed that in identifying 'indigenous literary practice' we could look towards the indigenismo movement; indeed, the movement "eulogized the Indian heritage and cultivated the Andean languages through written literature" (Howard, 2010, p. 130). However, by drawing on the idea of a golden-age, Inka-inspired identity, the indigenistas inadvertently propagated a Spanish-imposed worldview in a number of ways. First, given the belief that without books there is no history (Mignolo, 1992, p. 323), the 'history' on which indigenistas based their authority presumably came from Spanish-authored historical accounts; secondly, bdespite using an 'indigenous' identity to authenticate their literary productions, in locating this indigenous identity in a mythicized, pre-Hispanic past the indigenistas tacitly under- mined the authenticity they set out to establish given that pre-Hispanic society, at least in a colonial world-view, was de facto pre-literate; finally, given that the fundamental beliefs of indigenismo came from the "non-indigenous intelligentsia" (Howard, 2010, p. 130), they would have been detached from indigenous reality. As indigenismo was propagated by the intelligentsia, it would have carried symbolic capital, and as such their ideas have entered into the national social imaginary. Despite their ubiquity, the literary productions of indigenistas then are products of mestizo, elite social practice, and I therefore argue that we must be cautious in identifying them as 'indigenous.'

Standardization of Quechua

In light of the previous discussion of the symbolic violence inherent in the writing of indigenous lan- guages, it is of interest to consider how bilingual education projects have positioned themselves with regard to orthographic standardization and the effect this has had on 'indigenous literacies' (Hornberger, 1992, p. 198). Given that any language planning activities which start with a primarily oral language will require its adaptation to written form (Howard, 2007, p. 303) and that the search for an adequate alphabet is tantamount to a search for standardization (Coronel-Molina, 1997, p. 12), the alphabet adopted by the EIB (educación intercultural, bilingüe -or intercultural, bilingual education-) program is therefore of consequence.

The EIB program is operational throughout the Quechua-speaking Andean region and aims to educate the Quechua-speaking communities to read and write both Spanish and Quechua.

The standard orthography adopted by PROEIB Andes, the university responsible for coordinat- ing EIB, is not accepted by everyone concerned with language planning. An especially contentious issue is the number of vowels used to write Quechua.

PROEIB Andes, and most professional linguists, support a three-vowel system, whereas the Academia Mayor de la Lengua Quechua (Academy of the Quechua Language and here- after the Academia) and the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) support a pentavocalic system. Given that ''[e]ach group has its own agenda and its own ideologies which influence the differing approaches'' (Coronel-Molina, 1997, p. 7), it is worthwhile to consider them briefly to reveal how these various actors position themselves in relation to the question of 'indigenous literacies.'

In very straightforward terms, the Academia argue that they, as ''language aficionados'' (Coronel- Molina, 2008, p. 324), have always written Quechua with five vowels and so it should remain that way; meanwhile, the SIL claim that speakers 'on the ground' write using five vowels and therefore this should be accepted as standard. On the other hand, linguists use formal reasoning to show that Quechua has only three underlying vowels, arguing that only these should be used in the standard orthography. On the surface, then, it may seem that the SIL and the Academia favor the 'indigenous' in indigenous literary practice; however, I argue that closer analysis shows that this is not necessarily the case.

Underlining the three/five-vowel debate is the notion of authenticity (Hornberger & King , 1998), more specifically where the authenticity of the 'correct language' is located in each of the discourses presented. The Academia's cultural framework is elaborated from the tradition of indigenismo, and as such they use Cusco, the Inka, and an imagined indigenousness to underline their authority. To use James Costa's terms, for minority languages history becomes a "charter myth" (2010, p. 1), a source of language legitimization. The Academia's Cusco-centric ideolog y can be seen as part of a wider sociopolitical goal of estabishing a pan-Andean nation (Coronel-Molina 2008, p. 324), more specifically the re-establishing of a unified Tawantinsuyu (Inka empire). In light of their sociopolitical aims, I suggest that the Academia's actions are in line with Benedict Anderson's notion of the imagined community (1991) whereby language becomes the central tenet of identification. However, the Academia, in referring to rural Quechua-speaking people, but not to themselves, as 'indigenous' (Hornberger, 1995, p. 194), draw a boundary which results in their imagined linguistic community being separate from an indigenous reality and, as such, the literary practice they promote is ring-fenced as the preserve of a non-indigenous elite.

The SIL, on the other hand, emphasizes the importance of "community-based workshops and mentorships" in developing alphabetic norms (SIL - Multilingual Education, p. 9) and claims that it is easier for speakers to understand a five- vowel system. What the SIL does not take into account is that most speakers have learned to read and write in Spanish (which has five canonical vowels) before they do so in Quechua, explaining why it is easier for them to use five vowels (Howard, 2004, p. 101).

The SIL's position can be understood to be symbolically continuing colonial practice inasmuch as indigenous liter- acy is arrived at only through explicit reliance on Spanish conventions. It is interesting to note that some speakers claim a five-vowel system not because it is easier, but because that is what they read in the Bible and "since the Bible [is] liter- ally the word of God, it contain[s] the 'correct' way of writing Quechua, in contrast with other texts that [use] other Quechua orthographic norms" (De la Piedra, 2010, p. 108). This not only demonstrates how the authority of the book has entered into Andean cultural consciousness, but could also suggest another reason that the SIL (who are, first and foremost, a proselytizing organization) support a five-vowel system so as not to undermine the authority of the ' Word of God' which they set out to promote.

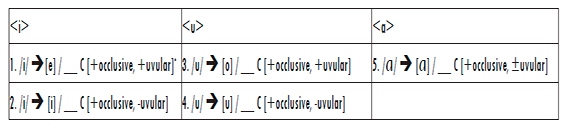

Contrary to the Academia and the SIL, the Quechua linguists' position is explicitly academic. They promote a tabula rasa argument taking Quechua away from Spanish phonographic rules and elaborating phonographic rules based on the internal structure of Quechua. They posit three underlying phonemes with allophones existing in complementary distribution (see Table 1). This approach can be understood in terms of decolonization in which Quechua is distanced as much as possible from the influence of Spanish. Although the 'technolog y' involved remains the same, the way it is used is specific to the communities using it. The focus placed on the socio-cultural element of education in the EIB program (see PROEIB -'Estructura y organización curricular') means that literacy is embedded in an indigenous social context and, as such, a person can have literacy competence whilst maintaining their indigenousness in a way that they cannot if literacy is always seen as the pre- serve of the other (De la Cadena, 2000, p. 6).

Despite some cases in which 'standardized Quechua' is seen as over-homogeneous and not reflective of the full gamut of Quechua varieties (see, for exam- ple, Howard, 2010; 2007, p. 333), it is widely recognized as the accepted written form of the language (presumably given the wide reach of EIB projects). That is not to say, however, that its teaching is not met with some suspicion or reticence. A general concern raised about EIB is that Quechua is taught to pupils to maintain social categories and disfavor social mobility (García, 2003, p. 71), i.e. to impose indigenousness on them from the outside. This belief can be seen in light of Nancy Hornberger's observation that often ''the school, though physically located within the community, is not a part of the community'' (1987, p. 221). I argue that whilst the 'technology' of literacy may have been accepted as compatible with indigenousness, the way it is presented in school is still often seen as other. I suggest then that we can only meaningfully begin to talk about indigenous literacy when its form, the social practice in which it is embedded, also emerges from an indigenous reality.

Table 1 Showing simplified transformation rules for Quechua vowels preceding occlusive uvular consonants(Base don Howard, 2007.,p. 323)

*Rule 1 reads (for example): underlyng /i/ is realized as surface [e] when it precedes an uvular, oclussive consonant, i.e. [q], [qh ] or [q, ]

'Social literacies'

In considering the way in which literary form can be indigenous, I explore two examples of located practice concerned with letter writing in the Andes. Letter writing forms an interesting topic of discussion for two reasons: first, due to changing economic situations and children moving into the city to work, letter writing has become a part of social practice in many indigenous communities and is therefore a new practice used in response to a specific societal need (Lund, 1997, p. 186; Zavala, 2008, p. 885). Secondly, the fact that letter writing also exists in a European context emphasizes the importance of adopting a critical, 'social literacies' framework (Purcell-Gates, 2008; Street, 2009); as we shall see, what we understand as letter writing is not universal, but rather depen- dent on a specific social context.

The first example is interesting in that its focus is on 'non-literate' people. Although this seems paradoxical, the letter senders dictate their letters to scribes who write down what has been said before sending the letter to their relatives who work in the city. The relatives who receive the letters are often themselves also non-literate and so rely on the person delivering the letter to tell them the message. In this instance, the person delivering the message does not simply read the contents of the letter to the addressee, but instead uses the letter as a starting point from which they elaborate the message as based on the conversation that took place during the composition of the letter (Lund, 1997, p. 192). If being literate is equated with the reading and writing of alphabetic script, the sender and receiver in this case are both non literate; however, what this example shows is that literacy in this instance is not a solitary practice, but one that functions at a community level. The senders, scribes, messengers, and receivers are all part of the literary practice of letter writing and reading. It is perhaps not too implausible to consider this literary practice by analog y with khipu literacy. In this vision, the scribes and messengers are nalogous to the khipu kamayuq inasmuch as they are gate-keepers to the meaning contained in the letters; the letter-as-object becomes analogous to the khipu itself, serving as a mnemonic device, encouraging the messengers to elaborate on the encoded words, and also acting as a means of "authenticating the oral message" (Lund, 1997, p. 192). Although the specificity of letters means that the encoder and the decoder are separated in time and space, I believe that this analog y holds and lends support to the case for adopting a 'social literacies' framework as it opens up the possibilities of understanding literacy practices in their broadest sense, a case which is further supported in the second example we will consider.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the practice outlined by Virginia Zavala (2008) is the way in which the written word is used to create emergent meaning, a process more readily associated with oral discourse than with text-based literacy (Bauman, 1984, p. 11). Zavala focuses on the sending of encomiendas (small consignments), the need for which comes from the same social context as letter sending. Whereas a letter is used to communicate information between the sender and the receiver, the encomienda, in addition to a letter, usually contains food, textiles, money, etc. and can therefore be seen as an example of both a material and information exchange. Unlike a letter, the information exchange in the case of the encomienda is directly linked to the material exchange inasmuch as each material element is bound up with its corresponding written accompaniment (Zavala, 2008, p. 886). Zavala highlights that as the encomienda is an important social activity, it is put together over the period of a couple of months to show that the sender is thinking about the receiver the whole time (2008, p. 886). Given the relationship between the written and the material, the writing is synchronous with this process of putting the package together, the implication of which, when the encomienda is received, is that meaning is created through the interaction of the material object and the accompanying written text. Zavala offers a concrete example in which a mother writes to one of her daughters that she is to call her other daughter so that the sisters can share the potato she has sent (2008, p. 887). This example highlights the active and emergent quality of the meaning whereby the emergent, true meaning of the message is constructed through the physical meeting of the two people and their ensuing social interaction. There is a blurring between practice and event in the same way that in oral storytelling there is often "a blurring of the boundaries between the story telling and the story told" (Howard-Malverde, 1989, cited in Howard-Malverde, 1990, p. 4).

It would be overly simplistic to claim that these examples of letter writing show a return to pre- Columbian literacy; indeed, it is likely that such 'new practices' have only come to light given our wider understanding of literacy and not because they are completely new. What can be said is that literacy practice is being used by indigenous people for their own ends and in their own distinct ways.

Although these practices still rely on European alphabetic literacy, the degree to which it is hybridized with non-European literary form sees the symbolic power of European alphabetic literacy challenged. Perhaps like the Mayan Chilam Balam2, 2 in a (post-) colonial context, cultural hybridization may be a useful tool indigenous peoples can use to resist dominant socio-cultural powers (Howard-Malverde, 1997, p. 15); that is to say that by using the technolog y of alphabetic writing in their own way and applying it to distinct forms, the power afforded by literacy can truly be put into the hands of indigenous people. What is clear from this hybridization is the need to move beyond entrenched-traditional concepts of literacy and look not only at literacy as a social practice as it enacted by social actors, but also to involve those actors in the definition of what they consider to be literacy practice. Therefore, any implementation of the UN and UNESCO declarations needs to avoid overly simplistic notions of literacy and empower indigenous peoples in decision-making processes.

Conclusion

This paper has shown that the notion of indig- enous literacy is not tantamount to the writing down of indigenous languages, but involves a con- sideration of social practice and the extent to which this practice is embedded in indigenous realities. It has been shown that the colonial ideologies of literacy, both in terms of technolog y and form, led to the imposition of a European framework which sidelined indigenous actors. These ideologies influenced what was recognized and accepted as literacy during the colonial era and continued to affect literary practice into the twentieth century. The debate surrounding Quechua standardization was explored to illustrate that the decolonizing of the European alphabetic technolog y is a difficult process and does not ensure that literacy is placed in the hands of indigenous communities if it is still circumscribed by imposed forms. Finally, in considering examples of letter writing in indigenous communities, it has been shown that in order to understand and implement the UNESCO and UN declarations from which we began, we need to take a broad, socially constructed view of literacy as a practice and, ultimately, in order to define indigenous literacy, we must shake off our preconceived ideas and listen to the voices of those who take part in these practices.