Introduction

In oral, written, or signed communication form, the interview technique has a negative or positive impact on certain social and linguistic situations. This impact is due to sociolinguistic implications of its application in a multilingual context depending on (a) sociolinguistic traits of the interlocutors-who may belong to one or more speaking communities, language attitudes, and ideologies; (b) interview context-space, format, and situation; and (c) sociolinguistic communities and their relationships in terms of language contact, sociological distance, language ideologies and policies, and linguistic conflict.

In this sense, the ecology of pressures allows the displacement of minority languages to be analyzed, (Terborg, 2006; Terborg & García, 2011). This model gives key factors to understand this process as a dialectical pulse between different communities’ understandings of what the language management and sustainability should be. Thus, if the relationship of power between two linguistic communities becomes asymmetric and troubled, then every attitude, behavior, and speech act are transformed into a pressure that tries to impose the exclusive use of one language in communication (Terborg & García, 2011). Indeed, some interlocutors will try to configure the state of the world as a monolingual ideal where their language abolishes the use, presence, and existence of any other language. Thus, the other language is minoritized, undervalued, and denied any function and justification of use. Therefore, an ideological interest prevails over a communicative intention, and this interest intends that the interlocutor-member of the other group-assumes the ideological logic to control and transform “the other” by the exercise of power (Van Dijk, 1998, p. 162).

Thus, a speech act such as an interview can be transformed into a little communicative pressure through which one of the interlocutors consciously or unconsciously, persuasively or forcefully, imposes on the other her/his own language as the exclusive one (Calvet, 2005, p. 82). Therefore, this choice by researchers does not result from negotiation nor communicative facility (Terborg & García, 2011, pp. 46-47). These implications would concern communicative effectiveness, generation of rapport, access to the primary and deep dimension of meaning and symbolism, the fluency and flow, spontaneity, and breadth of responses; in short, the quality of information in exchange for a false sense of security, control, and conduction of the interview. Thus, linguistic choices ignore that the multilingual background of a text or discourse is a form of reinforcing social inequalities through interview and translation (Welch & Piekkari, 2006; Steyaert & Janssens, 2013). Hence, where the conditions for an equitable and symmetrical use and valuation between speakers’ communities is non-existent, the interview carried out through a language that represents cultural, social, and political hegemony ends by serving to reproduce an unequal, asymmetric, and hierarchical epistemic relationship.

Therefore, the apparent comfort, facility, and methodological control through and by the interviewer could generate discomfort, difficulty, and insecurity in the interviewee when the interview language is a dominant language in a monolingualistic context. Even in the case of shared linguistic ability, language switching, or the use of a minority language, this linguistically minoritizing interview -LMI- (Figueroa Saavedra, 2021) occurs when the researcher-interviewer, intentionally or not, chooses the dominant language as interview language with a researched-interviewee speaker of minorized language. This happens by lack of mediation and translation resources, linguistic and communicative competence, or professional negligence, and by relationships of power against those who do not belong to the same sociocultural researcher’s status. This also occurs with students as researchers in formation into postgraduate programs. There, both teacher-researchers and student-researcher reproduce an academic linguistic ideology and unquestioned practices that refuse the use of minoritized languages as part of methodological inertia.

In an ethic-political and epistemological sense, these presuppositions need to be clarified. Some scholars, that previously reviewed this work, understood that this problematization departs from an attribution of intentions to eminently monolingual subjects. Thus, there is no reason in the language choice that they are considering minoritizing or dominating others because of their speaker condition in other language. In this way, the agency of these subjects here is not always setting out a responsibility in the design and application of monolingualistic or linguicist policies, only in the sense that their own actions take part in and belong to a minoritizing sociolinguistic context. Therefore, as a result of pressures, the intentions and actions shape a certain conception, relation, and attitude towards the everyday linguistic diversity that respond to interests of a certain ideology and policy, represented, promoted, and approved by institutions. Whether or not this ideology is internalized or conscient among people or whether these people are affected by the activity of institutions for wanting to be members of these institutions, these institutional minoritizing behaviors act in accordance and convenience with this directionality and positionality that these pressures establish (Terborg & García, 2011, pp. 36-37).

Therefore, regardless of whether the researcher affects others, the result will be the same; that is, the creation of favorable conditions for the languages of others has no place. This reproduces the interests that originally motivate the pressures to establish the desire to do or not to do something (Terborg & García, 2011, p. 27). Thus, what language must or must not be used is insinuated in any way. Although one thinks that does not act against the other, one would be acting in favor of oneself. Thus, there is no counterpressure on the hegemonic language policy. Even, when we adduce or recognize ignorance, we should ask ourselves what creates ignorance about something daily present. That occurs because this state of ignorance is also the result of other pressures that establish what can be recognized or imagined and what cannot. These pressures are not evident precisely when the “state of the world” coincides with one intends to shape from the interest. Only when this state runs the risk of being modified does this pressure emerge (p. 38).

In our case, when now national indigenous language (NIL) speakers, students, and teachers are starting to know the General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples (GLLRIP), the NIL-communities present themselves using their language more. In addition, even the inclusive and multilingual intercultural approach is more transverse; thus, comments are more evident for perpetuating the hegemonic state of the world. These comments persuade or devalue any reflection or decision in favor of more equitable multilingual perspectives defining the research activity. Therefore, one wants to see the use of a NIL as unnecessary in the community and in texts. If students suggest they want to use their language to formalize or diffuse their work, they are dissuaded from doing so because that is unnecessary effort that complicates the mentor’s supervision or that is detrimental to the use of other languages such as Spanish and English, which are more convenient in the university contexts. This advice may be well-intended because it tries to give opportunities to succeed in society and academy, but it also closes the door on any opportunities that the research will be shared with the community in a sustainable sociolinguistic way.

Whether or not it is an openly linguicist attitude, the context generated is linguicidal because it does not take part in efforts and commitment that the Mexican university must assume in favor of epistemic and ethnolinguistic equity. This concern motivates the start of some kind of research that requires deeper approaches to the phenomenon and the opening of a debate on connotations and collateral effects of our work of which we are not fully aware.

This aspect is crucial to highlight in the current debate on both biocultural and linguistic sustainability and on inquiry and interview techniques (cf. Terborg & García, 2011; Bastardas, 2014). It also deserves to be dimensioned through the determination of its prevalence in local contexts and in the multilingual constellations that are drawn in the exploratory transit of current research projects (House & Rehbein, 2004).

The aim of this project is to verify how the LMI is present in beginner research within populations with minorized language speakers of Mexico. Thus, an attempt will be made to understand what prejudices, beliefs, and behaviors justify not using these languages, even in those cases where the language choice affects the methodological rigor and the social and professional responsibility of researchers towards collaborators. Specifically, the analysis will focus on how the researcher’s attitude as a speaker and bearer of monolingualistic thinking promotes speech acts that make invisible, discriminate, marginalize, or exclude the languages spoken by the interviewed communities.

Theoretical Framework

This section first reviews what the Mexican linguistic ideological context is like and then analyzes to what extent an LMI is a manifestation of a language policy even in the generation of knowledge.

Mexican Linguistic Nationalism as an Ideological Context

The political language ideologies of a linguistic community influence its members to favor some languages or variants over others (Silverstein, 1979; Fishman, 1989). Thus, they minimize or maximize their value through prejudices and attitudes. The hegemonic groups will tend to promote their own language by endowing it with all kinds of positive values to show it as a superior and prestigious language (Calvet, 2005, pp. 90-91, 141; Moreno, 2008: pp. 76, 96-103; 2016, pp. 105- 111), which in turn, will be a functional argument to legitimize its officialization. This process has historically shaped diglossic societies (Fishman, 1989; Calvet, 2005) and in the 19th century it turned into an absolute monolingualism in the form of linguistic nationalism with the concept of nation-state. This linguistic ideal showed a state of the world that would ensure an efficient social unity, identity, and equality (Heath, 1992; Bartolomé, 2006; Zimmermann, 2010).

The purpose of the linguistic nationalism is to generate a principle of identity unification based on a language or linguistic variety. Consequently, those who do not speak this language or variety would be excluded from a national or a civilizing model (Moreno, 2008, p. 112). This is more evident in the Mexican case, where the so-called tránsito étnico (ethnic transit) implies giving up on a linguistic identity for getting a national identity as a subject of law (Bartolomé, 2006, pp. 24-29) that supposes the indigenous language is a stigma or impediment and considers the Spanish language a privilege or advantage. Although there are laws and rights as the GLLRIP that protect Mexican languages as national languages, to Mexicanize the indio is an imaginary that has not yet reversed a monolingualistic and racist ideology(Montemayor, 2000; Muñoz, 2009; Horbath 2022).

This approach leads to one language being considered the “official language” in detriment of other languages in the national territory because they are not hegemonic. The other languages are relegated from the public sphere and social communication, from mass-media, educational system, publishing industry, etc. Whether in a coercive or persuasive way, the state apparatus and social structure creates pressures to force those who do not belong to the national linguistic community to assimilate the language of the country and to assume in a pragmatic way the need to substitute their local language for the national or international language most socially valued (Spolsky, 2010, pp. 64-67; Muñoz, 2010, pp. 1244-1245). This monolingualism by norm is an officialism and an image of the power associated to a national and global society where the Western societies show themselves as monolingual although they have the presence of multiple languages and varieties (Rothman, 2008). This idealization has other effect more than a hierarchical supremacy, it represents an “obliteration of an alternative way of construing knowledge” (Bennett, 2013, p. 171) when linguistic inter/nationalization of research implies a translation into hegemonic languages that sometimes creates a different kind of knowledge away from the original knowledge of a subaltern culture (Bennett, 2007; 2013). Even this epistemicidal translation could be shown (or be seen) as a non-translation, an original text, or a possible source of unknowledge (Monzó-Nebot & Wallace, 2020, p. 8). Thus, Linda Tuhiwai Smith warned us about how the scientific production does not allow the “other” to recognize itself in our research because its significance is in its own language and textuality and in the translation’s limits (Smith, 2008, pp. 82-85, 43-47). Therefore, it is important to listen and to show the original voices, even more in an academic textual world that invisibilizes subaltern people.

In Mexico, this thinking has been relevant since the 1870s, when the Academy of the Mexican Language started a linguistic intervention aimed at creating a standard Mexican Spanish (Heath, 1992, pp. 259-260). This standard language gave unified linguistic identity to an ethnolinguistically diverse society. The intellectuals of fin-de-siècle claimed this goal to guarantee both a solid national identity and the modernization of the country (cf.Altamirano, 2011, p. 209). Likewise, the politician Justo Sierra, for example, advocated raising “a national language over the dust of all languages of indigenous roots, to create the primordial element of the nation’s soul”1 (Sierra, 2004, p. 37). Since the end of the 19th century, the presence of indigenous languages was considered a problem, a trait of ignorance. Castilianization was employed as an indicator of literacy and modernization. Anything that was contrary to this project was an obstacle to progress and a threat to the homeland (Heath, 1992, pp. 123-131, Montemayor, 2000; Morris, 2007).

After the Mexican Revolution, the Criollism and Indianism gave way to one Indigenism that did not eradicate this thinking although it defended a more conciliatory and planned position where bilingualism was an expression of integration. An educational subsystem aimed at facilitating the literacy and professionalization of indigenous people arose in the 1930s-1940s. Paradoxically, this persuasive method did not allow the dissemination of a national multilingual image beyond the “indigenous communities” and made the institutional, media, editorial, and professional visibility of languages difficult for the public. Henceforth, the access to primary education and Spanish-centered book culture-despite giving it a bilingual and bicultural character-was seen as the best means of achieving an only Spanish-speaking nation. Thus, the NIL monolingualism is a disadvantageous condition and an educational problem, but Spanish monolingualism is an advantageous condition and the solution (Montemayor, 2000, p. 72). There is a linguistic penalty and an ethnic penalty since if it is not possible, a fast (whitening) biological miscegenation at least linguistic homogenization could establish a monocultural society according to a kind of linguistic racism and cultural ethnocide (Bartolomé, 2006, pp. 72-73).

The LMI as a Manifestation of a Language Policy

The linguistic policy towards the indigenous languages of Mexico created conditions for using Castilian-centric and Castilianizing interviews in social research. A first example is the survey of the General Census of the Mexican Republic of 1895, in which a precise instruction to the interviewer about the item Idiomas (“languages”) said that he should

[…] write the native language name that is commonly spoken, such as Spanish, French, English, etc. or the indigenous language name, such as Mexican or Nahuatl, Zapotec, Otomi, Tarasco, Mayan, Huastec, Totonac, etc.; for the person who speaks Spanish and an indigenous language such as Otomi or Mexican, Spanish will preferably be recorded. (INEGI, 1895)

Thus, declaring to speak Spanish made anyone, ipso facto, a member of the Spanish-speaking community. This ideological bias, that is printed through the registration of response, was intended to show a modernized Castilianized country. The consequence is an underreporting of bilingualism, later incorporated. In 1921, the General Census would ask for the first time, “Do you speak Castilian (Spanish)?” and later “What other language or dialect do you speak?” With these questions the bilingual population is recognized. Here the bias has more to do with the possible analyses from what is categorized as “bilingual.” It was not a question of making up the numbers but of precisely evaluating the effect of Castilianization on linguistic displacement and correlating degree of literacy with bilingualism.

As early as 1895, the question was if one could write and/or read, but until today, the question implied that there are only literate persons in the Spanish (or foreign) language, not indigenous languages. Even the Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010 (Population and Household Census, 2010, INEGI, 2010) determined if a person was an indigenous speaker through the following question, “What dialect or indigenous language do you speak?” Moreover, this census identified the illiterate population by asking, “Can you read and write a message?” Neither the language nor the reading and writing abilities is distinguished here. This constitutes an invisible, unthinkable, or irrelevant datum.

These censuses are an early example of how the Mexican researcher approaches linguistic reality through an interview. These questionnaires were not intended to confront the national multilingualism, but to see if the imagined community of a Spanish-speaking Mexico took on a gradual and unstoppable shape. Given the evident multitude of non-Spanish-speakers, the presence of pollsters speaking native languages or interpreters was never mentioned. Similarly, an indigenous interviewee had to be bilingual, but a non-indigenous interviewee did not have to be, to the point that a member of an indigenous culture who only spoke Spanish should no longer be considered indigenous. Neither the creation of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages, the promulgation of the GLLRIP in 2003-which recognizes NILs in equal rights with Spanish-nor the General Law of People with Disabilities in 2005-where the Mexican Sign Language (MSL) was established too as national language-has removed this imagined community at the beginning of the 21st century. This means that the right of every Mexican citizen to write, speak, or sign in a national language of their choice has not affected how researchers pose questions.

Method

This case study aimed to (a) corroborate whether in postgraduate theses prejudices were manifested through no pertinent linguistic designs, and (b) establish prevalence of the LMI. To achieve this goal, a documentary, descriptive explanatory review, and an analysis of items such as type of interview, interview language, linguistic condition of the target people and the researcher, linguistic resources and support received, and the textual presence of NILs were made of 77 postgraduate theses written by students from Universidad Veracruzana (UV). This university was selected for three reasons: (1) Veracruz is the third state with the highest presence of NIL speakers in Mexico, representing 9 % of inhabitants (8 % of whom were not Spanish-speakers) who speak Nahuatl, Mixtec, Totonac, Chinantec, Teenek, Zoque, Popoluca, Tepehua, Zapotec, Mazatec, Otomi, and Mixe (INEGI, 2010; 2015); (2) the UV encourages research-intervention projects in regions and groups where NIL speakers live; and (3) the UV has an open access repository of postgraduate theses (https://cdigital.uv.mx/) that allows to build a corpus of research dissertations.

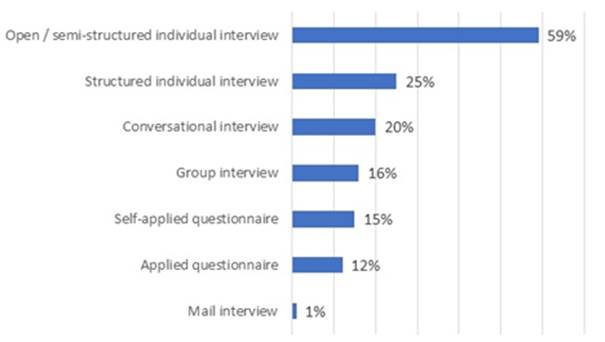

The selected theses (88% master, 17% doctorate, and 3% specialty) met the following inclusion criteria: (1) It applied the interview as data collection technique, (2) it was done in spaces or groups with presence of NIL speakers, and (3) it was written in 2002-2019, considering that the GLLRIP supposes de jure recognition of a preexisting situation in Veracruz. The majority belonged to the Humanities area (71%), and to other areas: Biological-Agricultural-Ranching (14%), Health Sciences (6%), Technical (5%), and Economic-Administrative (3%). They represented a wide variety of application of quantitative and qualitative interview types (Figure 1). The interlocution with NIL speakers was in each format, which means that in any case, the possibility should be foreseen that some interviewees might want to carry out the interview in their NIL for which purpose protocols and guides should be adjusted and should still be planned beforehand.

Findings

The review and textual analysis allowed the LMI and its forms of manifestation to be identified. It showed how certain ideological assumptions promote ways of representing the populations studied depending on monolingualistic imagined communities. However, it was also possible to find representations reflecting the multilingual reality according to the characteristics of the populations interviewed. The LMI is not expected to be developed thanks to the neutralization of linguistic biases in the communication and inquiry processes.

Presence and Prevalence of the LMI

Spanish, as a vehicular language in the academy, implied that any work implicitly must be done in Spanish to facilitate review, discussion, and evaluation, regardless of its recipient. Thus, 83% of the theses designed interview protocols, firstly in Spanish, and presumably another 8% did the same because the writers did not make a clear or explicit methodologically framework. Only 6% prepared bilingual questionnaires, and another 3% did them only in NILs. This means that either the researcher assumed the NIL-population is bilingual and can communicate in Spanish or that the pollster or interviewer would not ask the questions to a monolingual NIL speaker. This condition was not even estimated as a variable or filter question.

Regarding the application of questions, 91% of the samples made it clear that they were made in Spanish, 2% did not declare it, and 7% had to apply it in NILs with the help of interpreters by sight translation or applicators who improvised questions in the interviewee’s language. This urgent translation-interpretation should guarantee accuracy and, in the case or questionnaires and guides, a measurement and cultural equivalence (Behr, 2018). Usually, it did not happen due to haste or lack of preparation.

The inertia to use the dominant language was too evident in the case of interpreters, translators, or transliterators in the d/Deaf community, as a problem of monolingual Oralism or oralizing monolingualism (Hernández-Barrientos, 2022, pp. 49-50). Thus, the interpreters/transliterators linked a spoken language or an official sign language from a social and cultural positionality. This makes us wonder if they “would accept the Community by embracing its language or would they inadvertently further oppress the Community by rejecting its language” (Cokely, 2005, p. 13).

This positionality, also associated with centers of thinking where power and knowledge are ideologically connected, requires a community point of view and participatory research if one wants to reveal the inequalities and asymmetries that are not present in the public policies and academic debate nor in the agenda for knowledge production. Thus, all procedures and methods that involved an interpreter-researcher (or practisearcher) mediating and collecting data in real-life context must be reexamined to understand how they/we are involved in powerful ideologies and in the negotiation of meanings (cf. Pöchhacker, 2006; Turner & Harrington, 2014; Wurm & Napier, 2017, Bendazzoli, 2016).

Although there was consciousness of how this biases the tool, it was not a general reason to rethink the questionnaire or guide, nor the need to have them initially done in the local language. This was not due to ignorance of the reality or of the method. In fact, one researcher pointed out the importance of linguistic adequacy as a previous step to an interview application. She stressed the following: “During the interview, we tried to use a simple and informal vocabulary to generate a cordial and respectful atmosphere, in accordance with what was proposed by Exposito (2003) and FAO et al. (2008)” (De los Santos, 2019, p. 35). There was always a methodological need of every interviewer to adapt to the linguistic interviewees’ characteristics and allowed them to choose the interview language (Giles & Powesland, 1975; Rubin & Rubin 1995, p. 173, Valles 2007, p. 108).

Another thesis affirmed the following: “The loss of the mother tongue is another factor that favors the disappearance of traditional knowledge, since this knowledge is transmitted orally and very few are documented. It is thus recommended to include mother tongues in ethnobotanical work” (Rodríguez, 2019, p. 35). However, although this remark intended to correspond to a dissemination of research findings in NILs, the unstructured interview was performed, and the brochures were written in Spanish. Thus, 38 % of researchers were unconscious of this problem, or else did not identify NIL speakers in their target populations. This means they either denied or hid this data in the contextual framework and the description of the sample. The remaining 61 % did not react in an inclusive way although they did manifest a knowledge and awareness of this fact. They did not even know how to face the methodological challenge when they realized their language choice causes biases:

If we consider Nahuatl as the first language of coffee growers, the interviews, which were carried out in their entirety in Spanish, face the limitation of not being able to capture in their majority the processes of understanding and perception of reality, since, depending on the culture, words may have a more expressive but less practical function to reflect these actions. (Elizondo, 2015, p. 78)

In some cases, the researcher realized the study group was using an NIL because the interviee gave “very brief and even vague” answers in Spanish. But instead of encouraging them to respond in their language, their Spanish was used to highlight and to justify the “apparent shyness and passivity” of young NIL speakers as an explanatory datum (Espinoza, 2012, p. 39). Hence, the determining factor that a person supposes in one or another language was obviated, since it alters both their manifestation and participation as social actor, as well as the character, depth, and clarity of the elicited information (cf.Sakamoto, 1996).

In other cases, although the use of Spanish was fluent and satisfactory, “when the topic was exhausted, or the topic gave rise to a passionate discussion between them, the Purhé would appear, leaving me completely out of the conversation” (Ayora, 2012, p. 121). Interviews in Spanish were still applied in these cases, but when the interviewees were aware of the use of an NIL, the researchers requested the mediation of an interpreter to understand local terms:

In a planning session between members of the MIMOSZ group, which was carried out in Spanish because most of members of the planning groups were unfamiliar with the Nahuatl, a Nahuatl-speaking facilitator sometimes participated in sessions doing translations of certain cultural aspects that some participants did not know. (De la Hidalga, 2019, p. 216)

In other situations, the researcher highlighted her/his inability to collect or assess all the available information. Other researchers sought the help of translators to reduce the risk of underreporting, information omission or inappropriateness of tools:

A pilot test was carried out to verify that the questions were simple and understandable for the community artisans, taking 10 informants as a representative sample. This procedure was performed at two different moments with the support of translators. This was important since, as mentioned […] in the community of San Pablito, there is a considerable monolingual population, particularly among women. […] It was applied with the support of local translators. (Rebolledo, 2012, p. 49)

They showed aspects that may lose or hinder the retrieval of relevant information in cross-cultural translation (Behr, 2018, pp. 9-17) by the lack of translator competences and by the lack of control. Regarding the language used, only 7 % was interviewed in NILs either directly or through translations based on a Spanish guide. Could it be assumed that this was because the researcher spoke one of these languages? This assumption is plausible. Of the thesis’s authors, all those who speak an NIL knew the linguistic reality, while 55 % who did not speak an NIL at least recognized it. But this was not a determining condition to choose NIL as the interview language. Both NIL speakers and non-NIL speakers conducted interviews in Spanish. Furthermore, 75 % of NIL speakers did not interview in that language for some reason. Perhaps they felt the academic milieu or mestizo society is refractory to the use of an NIL in their documents, although at UV there are schools (Universidad Veracruzana Intercultural, Instituto de Investigaciones en Educación) whose internal regulations promote and guarantee the NIL’s use by students in examination and qualification processes. However, this means that only the degrees taught by 2 % of schools allowed this possibility and tried not to breach current legislation.

In some degree and postgraduate programs (Licenciatura en Gestión Intercultural para el Desarrollo, Maestría en Educación Intercultural), NIL speakers students used their mother tongue in dissertations and presentations with the help of interpreters (Figueroa-Saavedra et al., 2014; Escobar, 2019). However, that is still unusual outside these schools, and it depends a lot on a favorable and inclusive teachers’ attitude (Pharao, 2016, p. 374). Thus, it is habitual for the student that wants to use their NIL orally or in written form to find opposition from teachers. They tell the student not to do it or they request a translation, which is a work overload. The teachers promote more Spanish and English in dissertations according to oligolingualistic ideologies (Hamel, 2013; Bennett, 2013; Despagne & Sánchez, 2021). Thus, no native Spanish-speaking students feel that it is not necessary, convenient, or relevant to indicate whether they used their mother tongue.

One case showed an interview guide in Spanish, but both the record of responses and the presentation were in Nahuatl. Thus, the methodological design and the instruments were adapted more to an academic audience and supervisors than to community (Sánchez, 2018). He said he translated the guide into Spanish and did not include the original. In other cases, the NIL speaker researcher did not use an NIL because the mother tongue was not required or should not be used in certain situations (Hernández-Luis, 2012; Cruz, 2018). Even if the answers were stated in an NIL, they were finally registered/translated into Spanish although many emic terminologies were included (Cruz, 2018). Then the intention of showing the epistemic value of original forms can be identified, but in the academic discourse, the construction of an epistemological infrastructure in the NIL as it happens in the translation (Bennett, 2013, p. 171) is lost. Whatever happens these processes were not shown well, and the source questionnaires and the original answers were missing.

It is true that it is not possible or advisable to use the local language in certain speaking situations. For reasons of respect or formality, the use of Spanish has become so prestigious that not using it can be interpreted as an insult. Sometimes, this “naturalization of difference” (Hill, 2007, pp. 147-148) implies negotiating which language is conditioned by assessment of the hierarchical use and prestige of a variety or language, and by a certain linguistic insecurity associated with the interlocutors’ status. Beyond a shared facility, the use of Spanish does not guarantee it is being used in an effective way, that is, it eliminates the linguistic insecurity in an effective communicative sense. This does not explain the systematic use of Spanish but acknowledges the logic that authorizes it in certain contexts as an approved use and acknowledges the ways of subverting discriminatory use and logic. This could be taken as an indicator or pressure of the same minoritizing process.

In contrast, 10% of non-NIL speakers recognized that the populations use their own language in interviews. They thus mentioned it in their work because they consider it a key factor to obtain valid and quality information. Some of them selected the most suitable interview model for a method: “First of all, we proceeded to define the kind of questionnaire, determining that the most appropriate was the semi-structured questionnaire since it is used in exploratory research” (De la Cruz, 2015, p. 33). In the interview language choice, they choose the one that suits the target population and ensures the information collection: “it was also decided that they would be applied directly by interviewers who were fluent in the Nahuatl language, due to the large presence of indigenous people that speak this indigenous language” (2015, pp. 33-34). However, the theses showed that the works embrace a variety of methodologies (Figure 2).

The interview type varied depending on its objectives and discipline. The adjustments in some cases evidently were necessary (Figures 2 and 3)-more noticeable in face-to-face interviews with a sample group-and with a greater anticipation of the NIL’s use. On the contrary, in applied questionnaires, only two cases were tools developed in several languages from the beginning. In the case of mail interview were made as an individual structured interview by questionnaire. Their monolingual designs in Spanish were not subject to any readjustment.

In applied questionnaires, it was necessary to translate or to use bilingual applicators, and to seek the support of interpreters. In other cases, the monolingual interview was not modified because of linguistic diversity. This could be justified pragmatically because the interviewer only identified non-NIL speakers, but this fact or initial approach excludes the chance of finding NIL speakers.

Mail interviews or self-administered questionnaires were done in Spanish because the researchers would think the NIL speaker is literate in Spanish alone. The absence of choices made the NIL speaker (and NIL-reader-writer) invisible to the researcher and did not permit the NIL speakers interviewed the possibility of recognizing themselves as NIL-literate when seeing a questionnaire written in their language. This is so much so that if research does not need to mention that a person or a community has literacy practices in its mother tongue, this datum is not used. As Welch and Piekkari (p. 425) mentioned, the need to reduce the translators’ payment may weigh in although it is necessary in those studies that paradoxically try to study reading practices.

In structured interviews, it is the other way around. There was a certain ease to write in Spanish. This ease was due to lack of skills in the mother tongue or also the already mentioned irrelevance (that is, exclusion) in the academic environment. Thus, the mention of the interview language used is not expressed although some interviews in the field were performed in a local language without the documents leaving record. This omission showed the research process as monolingual, or the researcher as monolingual Spanish-speaker.

This minimal inclusion of quotation verbatim in NILs is striking. Only 5 % of theses included it, and 9 % included terminology from NILs. This implies use of the language of the researched community, which may reveal pressures and prejudices that Castilianize an investigation, affecting validity, accuracy, and representativity of findings. This attitude that makes the NILs textually visible is not common. Then it is deduced that there should be compelling reasons contrary to the mainstream of methodological designs in Mexico to counteract this Castilianizing inertia. Indeed, there are academic entities or programs that state that the theses must have congruence between the interview language and the interviewees’ language, both in tool’s design and in conversational performance. For instance, in the master’s degrees in Anthropology, Education for Interculturality and Sustainability, and Public Health some research achieves linguistically advantageous interviews for both sides (Welch & Piekkari, 2006, p. 422) by opting for the mother tongue.

Non-Minoritizing Linguistic Use of Interviews

Two master’s theses performed responsible interviews before linguistically minoritized communities. The first case is from the Institute of Public Health that sought to find out the level of knowledge and opinions about HIV-AIDS among Nahua people in Zongolica region. This research was supervised by me as mentor, and I observed how the researcher was refocusing the problematization, given that initially she (and the health services) saw the condition of NIL speaker as a risk factor in high morbidity in indigenous communities. During the research she realized the risk factor that the public health promotion campaigns was always made in Spanish.

Thus, a Spanish-Nahuatl questionnaire was designed to be applied in two Nahuatl speaking municipalities. She reached this conclusion after noting that the results of previous consultations to indigenous communities lacked reliability, as they were only undertaken in Spanish (Suárez, 2009, p. 16). The purpose was to achieve a more precise diagnosis that would facilitate decision-making processes in health services, by allowing the interviewee to choose the interview language and to use a colloquial language.

The researcher made one version in Spanish and two translated versions (Figure 4) using two varieties of Nahuatl (p. 41). This work took more than two months, as it was necessary to review the intracultural significance. “We were looking for words that had a similar meaning in Spanish as in Nahuatl and not just a ‘mere translation’ that led to the misunderstanding of what they wanted to ask” because “on many occasions the translations produce alterations that put texts written in Spanish as the source language in Nahuatl and that do not make sense for the Nahuatl speaker because they do not have a logical and correct grammatical construction” (p. 42). She piloted the versions, taking care of the unity of concept in wording of questions, to avoid biases. Specialized Spanish terms were also simplified and adapted to plain language even though explanations were included by the pollster. They identified difficult concepts to operationalize in emic categories, for which there were lexical gaps, absence of formalized terms, conceptual differences, or taboos. The researcher was impelled to assess the original response, as verbatim, its own meaning and semantic validity (p. 42).

The interviewers were trained (because of the privacy of some questions) and grouped in mixed pairs, male, and female, one of which was a Nahuatl speaker. Thus, the possibilities and eventualities that the interview could face were foreseen. It was guaranteed that the interviewees would receive the interviews in their homes, increasing confidence levels, and ensuring that questions were understood in the text. This structured personal interview was able to respect the random sample design and did not involve an invasive, inefficient, or irresponsible method on behalf of health services.

With respect to the ethnographic interview, one might think that all ethnographic interviews tend to choose the interviewee’s language, although there are cases where not even the condition of NIL speaker ensures the interview is going to be conducted in NILs. However, in this thesis from the Faculty of Anthropology, the researcher, a native Nahuatl speaker, undertook the interview in their own language to carry out a study on the system of charges in Hueycuatitla, Huastecan region. To this aim, he proposed a bilingual interview guide (Figure 5).

His initial approach was a bilingual interview. The interviewer evidenced her/his condition as an NIL speaker and wanted to make the optionality of the interview language clear:

Most of these interviews were conducted in Nahuatl, except for the mayor and the legal advisor. Even though both are fluent in Nahuatl they chose to respond in Spanish. I would like to highlight those collaborators were always given the freedom to choose the language they wanted to speak, either Spanish or Nahuatl. All interviews conducted in the community were audio-recorded and transcribed. (Hernández-Osorio, 2015, p. 66)

This description is unusual. Normally, when the NIL-speaking researcher is a graduate, she/he is expected to speak only in Spanish, since the status and prestige of the academic degree must also be reflected in the language. Thus, in the communities, the graduates must speak and be spoken to in Spanish (F. Antonio Jauregui, pers. com., 3-5-2010). However, in the context he points out that precisely the wewetlakameh “only speak the Nahuatl language” (Hernández-Osorio, 2015, p. 117), so interviewing them in Spanish would have been limiting and inappropriate. In this regard, he insists on the lack of interpreters but shows it as a common occurrence despite the Castilianizing displacement in the community. Therefore, his condition as an NIL speaker is not hidden but rather shown as an advantage in addition to giving priority to the speech in local language. Thus, he includes verbatim in that language as a direct testimony. As an act of revaluation, in the case of Nahua graduates, interviews in Nahuatl evidence the knowledge obtained from its statement in Nahuatl reinforcing the status and prestige of that language as a means of knowledge.

Discussion and Conclusions

As is clear from this study, the LMI predominates, in the current context, in research works with NIL speakers, although now a new proposal of multicultural and multilingual national construction begins to be promoted (Morris, 2007; Lara, 2010; Valadés, 2014). This leads to the fact that this study recurring linguistic prejudices in the interview are identified but also an acknowledgement of the multilingual reality of Mexico as a new imagined community to which one must adapt, respond, and understand from the community’s own terms and needs is emerging. This is obvious in two theses whose methodology implies recognizing our responsibility to create a monolingual country that does not yet exist (Smith, 2008; Bennett, 2013; Rothman, 2008; Steyaert & Janssens, 2013). On the contrary, this study found other theses that even recognize a bilingualism but still do not contradict that monolingual imagined community. Those theses act in accordance with linguistic attitudes and prejudices that weigh on the decision of which language to use towards the Mexican NIL-speaking population.

The reason of the trend of interviewing only in Spanish probably is based on the belief that the process of Castilianization has been “complete” in Mexico, but above all that Spanish is the common language of all Mexicans, whereas the second language may be English-Spanish is not considered de facto a second language. Although standard linguistic procedures can occur based on a conception of Spanish as a lingua franca or common language, the use of only Spanish in a community that does not have the chance of using its language publicly is often seen as an act of imposition and suppression (Montemayor, 2000, p. 103). This linguistic monolingual interaction is by default an unquestionable and unnegotiable fact as the “default position” that occurs in the case of English monolingualism (Rothman, 2008, p. 442). This supposes a methodological inertia in the selection of methods that the beginner researcher applies.

Thus, applying known methods without reflection nor coherence in an interview, it is evident that postgraduate students probably were prone to perpetuate damaging forms of ignorance what cause a lack of internal and external validity and consistency (cf. Steyaert & Janssens, 2013, p. 136; Monzó-Nebot & Wallace, 2020, p. 20). The interviewer believed the interviewee was bilingual, which means the interviewee should (always) answer in Spanish. With this assumption, the tendency will be to use Spanish to facilitate design and reduce our effort, not to learn the language or pay for an interpreter or translator, which shortens deadlines. It is thus thought that the information had the same validity, precision, and significance in Spanish.

Another presupposition was if the interviewer found someone who does not speak Spanish, they would look for someone else (relative, neighbor, or official) to mediate or translate, interviewing them as if they were the selected person, that is, displacing the interviewee. The interviewers may ignore the sample element and look for someone else, as if the quality of information does not depend on the selection criteria, interviewee’s expertise nor suitability to the sampling method.

One more prejudice that is inferred on all conditions in written interviews (by mail, self-administered questionnaire, etc.) is that the questions were always formulated in Spanish because, if they are not illiterate, they are only Spanish literate since NILs “are not written,” “cannot be written,” or “it is not possible to teach how to write them” (cf. Rockwell, 2000, 2010; Hernández-Zamora, 2019; Figueroa-Saavedra, 2018, p. 105).

Thus, the theses authors, as an agent and administrator of language, unconsciously created linguistic pressure when they choose a hegemonic language as the unique option-even if there is an academic discourse or normative that proclaims the recognition of linguistic diversity-because there were not opportunities or interest in showing multilingualism. Thus, the marginalization and invisibility of minoritized languages-linked linguicide and epistemicide (Smith, 2008; Bennett, 2013) was naturalized, as one does not reflect on whether this signifies still another action that reduces the use value and status of minority languages. This explains the very high prevalence of the LMI in postgraduate research at UV.

Not even the GLLRIP managed to generate a sense of obligation between both researchers in training and those already trained-perhaps due to ignorance, lack of dissemination, complaints, and actions to enforce it. Thus, these academic uses and regulations continue to privilege languages of international knowledge. This preference even puts pressure on the researchers who speak an NIL to describe their reality through these languages, and, in the long run, to know it and make it known in the same way, assuming their inferiority and subalternity, and the non-validity in some research findings.