Burnout Syndrome is a phenomenon that has been widely studied in recent decades (Caballero, Breso, & Gutiérrez, 2015; Carlotto, Câmara, Otto, & Kauffmann, 2009; Carlotto, Nakamura, & Câmara, 2006; Costa, Leal, 2006; Domingues-Lara, 2016; Gradiski et al. 2022; Mota, Farias, Silva, & Folle, 2017; Osama & Blanco, 2021; Puertas-Neyra, Mendoza, Cárceres, & Falcón, 2020; Sañudo, Domínguez, Gutíerrez, Gómez, & Santos, 2012; Schaufeli, Martinez, Pinto, Salaova, & Bakker, 2002), has recently been included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), while burnout in college students has been an subject of research since 2002, the investigations of Schaufeli et al. Currently, studies such as those by Andrade et al. (2021), Caballero, Breso, and Gutiérrez (2015), Kong, Yao, Chen, and Zhu (2022), Mota et al. (2017), and Moura et al. (2019), have a greater focus on literature reviews on research already conducted, thus, it is noted a scarcity of studies aiming to analyze prevalence and associated factors.

According to ICD-11, Burnout Syndrome is defined as the resulting from chronic stress in the work environment, which was poorly managed and is divided into three dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and professional inefficacy (ICD, 2021). Burnout in academics, on the other hand, has been studied as an attempt to understand the phenomenon arising from the teaching-learning process, which compromise the well-being of the student in training phase (Mota et al., 2017). The university phase can be seen as a potential stressor and impact students' mental health (Ariño & Bardagi 2018).

The accumulation of stressors, prolonged and poorly managed, can cause the development of Academic Burnout. Academic Burnout is divided into 3 dimensions: the Emotional Exhaustion dimension, which refers to the lack of energy in relation to studies and the feeling of emotional exhaustion; the cynicism dimension, characterized as a cynical attitude and detachment towards studies; and Professional Inefficacy, defined as the feeling of being incompetent in studies, thus generating a difficulty in concentration (Andrade et al, 2021; Carlotto et al., 2009; Carlotto, Nakamura, & Câmara, 2006; Caballero et al., 2015; Mota et al., 2017; Osama & Blanco, 2021; Puertas-Neyra et al., 2020; Sañudo et al., 2012).

The academic population is prone to being affected by stress factors, however, health students are subject to feeling the impact of stressors to a greater degree, due to the following reasons: the demands of the course, the need to deal directly with people during practice, as they sometimes absorb the problems of these patients, and self-demand aiming for perfection (Ariño & Bardagi, 2018; Carlotto et al., 2009; Carlotto, Nakamura, & Câmara, 2006; Osma & Blanco, 2021).

The way stress is to be experienced, the cognitive and behavioral resources used, and the intensity of this exposure can lead to the development of burnout and directly influence the health-disease relationship. One of the ways to prevent burnout and regulate emotional exhaustion is to use coping strategies (Carlotto et al., 2009; Osama & Blanco, 2021).

Coping strategies are defined as cognitive and behavioral efforts aimed at managing and alleviating the effects of stressful events, internal or external, that exceed the individual's adaptive capacity impacting positively or negatively on his/her physical and mental health (Antoniazzi, Dell'aglio, & Bandeira, 1988; Dias & Pais-Ribeiro, 2019; Hirsch, Barlem, Maroto, & Aparício-Zaldívar, 2015; Osma & Blanco, 2019; Santana et al., 2021). The effective use of coping strategies leads to adaptation and overcoming of stress, otherwise reassessments may occur, in a feedback system, for the use of more efficient strategies, until the problem is resolved or the individual reaches exhaustion (Hirsch et al., 2015). Thus, coping is successful when it succeeds in ventilating the negative effects of a stressful event.

Furthermore, such strategies can be classified into three types according to their function, as follows: the strategies focused on emotion, referring to coping strategies that seek the emotional regulation of the individual, aiming to reduce the unpleasant sensations arising from the stressor; the strategies focused on the problem, in which occurs the attempt to modify the stressful situation, involving planning and problem solving; and the focused coping, which consists in the search for internalized beliefs and values with the objective of keeping the individual motivated to overcome the situation, regulating positive emotions in order to revalue the experience of threat in a challenging situation, interpreting it as a life experience (Dal'Bosco et al. , 2021; Dias & Pais-Ribeiro, 2019).

Studies by Carver, Scheier, and Weintraub (1989) specified the types of coping strategies originally proposed by Folkman and Lazarus in 1980, establishing coping styles (table 1).

Table 1 Coping Styles

| Coping Styles | Definition |

| Acceptance | Divided into two stages, the first in which the event is considered real and later is seen as inherent and natural.. |

| Searching for social support for emotional reasons | Defined by seeking support in order to receive compassion and validity of their emotions. |

| Seeking social support for instrumental reasons | It refers to the search for practical support, and for information from third parties |

| Active Coping | Characterized by the planning of consecutive actions, aiming to diminish the effects of the stressful event; |

| Moderate coping | The act of waiting for the right moment for action regarding the stressful event |

| Behavioral Disengagement | Defined as the failure to achieve goals that have a connection to the stressful event |

| Mental Disconnection | Characterized by the use of distractions from the stressor |

| Self-blaming | Blaming yourself and/or taking responsibility for stressful events |

| Focus on the expression of emotions | In which the stressful experience is emphasized, seeking to disperse negative emotions |

| Denial | It constitutes ignoring the existence of the stressor |

| Planning | Consists in the act of reflecting on effective strategies to deal with the stressor |

| Positive reinterpretation | Defined as the conscious act of re-signifying the event in a positive way |

| Religiosity | Based on the search for religious entrances to ease the stressor |

| Suppression of concomitant activities | Defined by eliminating distractors from the stressful phenomenon in order to keep it in focus |

| Humor | Turn to the use of jokes in relation to the situation |

| Substance Use | Use of psychoactive substances as a way to disengage from the ability to become aware of the situation |

Source: Carlotto et al., 2009.

In addition, social support is configured as a buffering strategy in the face of stressful events, defined as psychosocial and interpersonal processes perceived by individuals and coming from their close social network, usually consisting of family members, friends, and teachers, which has a function of seeking material, cognitive, and affective resources to resolve stressful situations (Arrogante & Aparicio-Zaldívar, 2017; Barrat & Duran, 2021; Caballero-Domíngues & Suarez-Colorado, 2019).

It is important to note that social support is subjective and does not refer to the quantity of supporters, but to the quality and satisfaction that the individual has from the support received (Almeida, Carrer, Souza, & Pillon, 2018; Dunn, Alexander, & Howard, 2022; Marôco, Campos, Vinagre, & Pais-Ribeiro, 2014). It can come from three sources: emotional, referring to the affection received, being strictly linked to the perception of being loved and appreciated; instrumental, which refers to practical or financial support; and informational, understood as the act of receiving information related to certain circumstances, such as decision-making (Cardoso & Baptista, 2014).

The low perception of social support is related to pathologies, in addition to producing psychological malaise and dissatisfaction with life, being considered an important variable in the process of stress and illness, establishing a negative relationship with burnout (Cardoso & Baptista, 2014; Dunn et al., 2022).

A Brazilian study with 192 nursing students from a public university in the interior of the state of São Paulo assessed their perception of stress and social support. The results showed that the average number of students' supporters was low in 59.9% of the participants, but despite this, the students were satisfied with their support network, 62% with low stress scores. The professional training domain was identified as the greatest stressor in 62.5% of the participants, thus stress was related to insecurity when entering the job market and the change of roles from student to professional. Students with elevated levels of social support satisfaction had a low rate of stress with theoretical activities (Almeida et al., 2018).

Thefore, burnout, coping and social support are interconnected. The coping strategies used effectively ventilate the effects of stressors, while social support as a coping strategy acts directly in the regulation of emotional exhaustion, so that the better the perceived social support network, the lower the levels of exhaustion, besides the fact that the lack of it constitutes a stressful factor, thus, concomitantly, social support acts as a risk and protection factor for burnout. With that said, the present study, according to the definitions of academic burnout, coping and social support, aimed to verify the prevalence of academic burnout syndrome and the possible correlations between its dimensions (emotional exhaustion, professional efficacy, and cynicism) with coping strategies and social support in college students from different health courses. The study also aims to evaluate the quality of social support perceived by students and its influence on the dimensions of academic burnout, to verify associations between the coping strategies used and the dimensions of academic burnout and to verify the influence of perceived social support and coping strategies as predictive variables in the development of academic burnout.

Methodology

Research design

This is a quantitative study in the form of exploratory research with a transversal period. Quantitative studies are fundamentally conducted to describe and/or analyze variables and frequency in large populations. As for the period, the cross-sectional study seeks to analyze a phenomenon in a certain time interval, cutting it up and breaking it down in its analysis (Cozby, 2003).

Participants

The sample was of the non-probabilistic type through snowball sampling, the inclusion criteria were to be attending courses in the health area, to be between the first and sixth year of graduation, to be between 18 and 30 years old and to live in Brazil. So, the sample comprised 173 participants, aged 18 to 30 years (M = 23.71; SD = 7.04), 154 (89%) were female, and mostly white (N = 138, 79.8%). The students were between their first and sixth years of undergraduate study (M = 3.2; SD = 1.54). Other characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Descriptive statistics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Marital or relationship status | ||

| Married | 21 | 12.1 |

| Single | 97 | 56.1 |

| In a serious stable relationship | 55 | 31.8 |

| Lives with the family | ||

| No | 136 | 78.6 |

| Yes | 37 | 21.4 |

| Has children | ||

| No | 22 | 12.7 |

| Yes | 151 | 87.3 |

| Graduation course in progress | ||

| Psychology | 107 | 61.8 |

| Other | 66 | 38.2 |

| Graduation period | ||

| Full | 38 | 22 |

| Morning | 24 | 13.9 |

| Evening | 111 | 64.2 |

| Beyond the regular subjects of the curriculum, do you take any other? Are you retaking a failed subject? | ||

| No | 19 | 11 |

| Yes | 154 | 89 |

| The course was his first choice | ||

| No | 107 | 61.8 |

| Yes | 66 | 38.2 |

| Has previous graduation | ||

| No | 26 | 15 |

| Yes | 147 | 85 |

| Currently works | ||

| No | 82 | 47.4 |

| Yes | 91 | 52.6 |

Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire: Composed of questions regarding: 1) Personal data: gender, sexuality, age group, race, marital status, children, and Brazilian macro-region; and 2) Professional data: course, educational institution, academic semester, choice option, previous graduation, and occupation.

MBI-SS - Maslach Burnout Inventory for students: Scale adapted for application in students by Schaufeli, Leiter, Maslach and Jackson (2002). The seven-point Likert-type scale (0-never; 6-every day) and proposes to evaluate burnout indices through fifteen questions that are subdivided into three subscales, being: emotional exhaustion (5 items); cynicism (4 items) and professional efficacy (6 items). In its validation, satisfactory results were found for each of the three subscales emotional exhaustion a=0.81, cynicism a=0.74, professional efficacy a=0.59. High scores on Exhaustion and cynicism and low scores on Professional Efficacy are indicative of Burnout. (Carlotto et al., 2010). The validity study for the use of the construct in Brazilian college students was conducted by Carlotto and Câmara (2006).

BriefCOPE: The instrument assesses 14 coping strategies in stressful situations through 28 items (2 for each strategy), using a 4-point Likert scale (1-I have not done it at all, 2- I have done it a little, 3- I have done it, and 4- I have done it a lot). The validation of the psychometric properties of this scale was performed in a Brazilian sample by Brasileiro and Costa (2012). The overall validation index of the scale resulted in α > 0.70, which is considered acceptable.

The Social Support Satisfaction Scale (SSSS): The scale is Likert type with five points (5- strongly agree; 4- mostly agree; 3- neither agree nor disagree; 2- mostly disagree; 1- totally disagree) and aims to assess the perceived satisfaction of social support available to the individual. It has in its total fifteen items, which permeate four dimensions, being them: satisfaction with friends, intimacy, satisfaction with family, and social activities. Scale with cross-cultural adaptation, submitted to reliability and validity test by Marôco et al. (2014) in a Brazilian sample, in its validation satisfactory results were found for each dimension; satisfaction with friendships a=0.656, intimacy α =0.656, satisfaction with family α =0.649 and social activities a=0.696. Data Collection Procedure

The project is in line with the ethical issues in research involving human beings proposed by Resolution 510/2016 (Brazil, 2016). Thus, the project was forwarded and approved by the Research Ethics Committee with the registration (CAAE No. 53907421.3.0000.5515). Data collection took place online through the method of dissemination in Snowball, the research link was shared in social networks through Google Forms and a free consent and participation term was made available, after fulfilling these steps an email was forwarded to each participant with the link to the sociodemographic questionnaire and the instruments. The estimated time to complete the questionnaire was approximately 20 minutes.

Data Analysis Procedure

Descriptive statistics were generated for the sample and two types of models were constructed, the first is a multivariate analysis of covariance, MANCOVA, (Field, 2018) and the second a moderation (Hayes, 2018). A Pearson correlation was also performed to understand the correlations between the dimensions of the SSSS and the impact caused on the dimensions of burnout moderated or not by coping. The software used was SPSS (Version 26) with the MACRO PROCESS package (Haukoos, 2008) (Version 4.1).

Results

Initially, the descriptive statistics will be presented, with mean and standard deviation, resulting from the answers obtained in the instruments, Sociodemographic questionnaire, MBI-SS - Maslach Burnout Inventory for students, Brief COPE (Table 3).

Table 3 Results MBI-SS, Brief Coping and ESSS

| MBI-SS | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | 14.179 | 7.107 |

| Cynicism | 7.012 | 6.495 |

| Professional Efficacy | 22.445 | 8.202 |

| Brief Coping | ||

| Substance Use | 5.832 | 1.475 |

| Self-blaming | 5.763 | 1.543 |

| Focus on the expression of emotions | 5.698 | 1.594 |

| Denial | 5.572 | 1.640 |

| Active Coping | 5.538 | 1.504 |

| Behavioral Disengagement | 5.318 | 1.627 |

| Positive Reinterpretation | 4.838 | 1.694 |

| Mental DisengagementMental | 4.780 | 1.748 |

| Religiosity | 4.769 | 1.668 |

| Emotional Support | 4.601 | 1.354 |

| Instrumental Support | 4.387 | 1.323 |

| Acceptance | 4.358 | 1.229 |

| Humor | 4.231 | 1.440 |

| Planning | 3.913 | 1.794 |

| SSSS | ||

| Satisfaction with Friendship | 15.942 | 3.413 |

| Intimacy | 13.283 | 3.022 |

| Satisfaction with family | 9.595 | 3.351 |

| Social Activity | 9.821 | 3.607 |

To understand the mean difference in instrument scores between sociodemographic variables a MANCOVA (Field, 2018) was performed. The analysis was implemented of the bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap procedure (1000 remaps, 95% confidence interval). Since a normal distribution was not obtained by the Shapiro-Wilk (p < .05), and Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p < .05).

The procedure aims to correct the distribution and generate more accurate confidence intervals (Field, 2018; Hayes, 2018). The variables age and year of graduation were entered as a variable, so in case there is a correlation between these and the instruments, their influence on the scores are corrected by the test (Field, 2018). The MANCOVA showed no statistically significant differences for the variables, follows Pilai's trait (Table 4).

Table 4 MANCOVA analysis

| F(gl) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.134(8. 149) | .344 |

| Graduation year | 1.370(8. 149) | .214 |

| Gender | 1.260(8. 149) | .269 |

| Race | 1.295(8. 149) | .250 |

| Marital status or serious relationship | 1.164(16. 300) | .059 |

| Lives with the family | 1.158(8. 149) | .328 |

| Has children | .574(8. 149) | .798 |

| Course in progress | 1.687(8. 149) | .106 |

| Graduation period | .987(16. 300) | .287 |

| Retaking a failed subject | 1.227(8. 149) | .287 |

| First undergraduate choice | .815(8. 149) | .591 |

| Previous Graduation | .426(8. 149) | .904 |

| Currently works | 1.224(8. 149) | .288 |

Thus, the sociodemographic data of the sample of health students did not indicate statistically relevant influences on the prevalence of academic burnout syndrome.

Next, a moderation analysis was performed, in which 12 moderation models were created to understand the impact of the dimensions of satisfaction with social support on the dimensions of burnout moderated by Coping, for this analysis Coping was adopted as a single measure (M=69.59; SD= 11.96). Table 5 follows, with the summaries of the models evaluated (Hayes, 2018).

Table 5 Prediction Models with Moderation

| Coefficient (B) | Standard Error | P | |

| Independent Variable: Emotional Exhaustion | |||

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction with Friends | .254 | .155 | .089 |

| Coping | .062 | .045 | .172 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with friends*Coping | -.001 | .012 | .913 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Intimacy | .02 | .188 | .882 |

| Coping | .08 | .045 | <.01 |

| Moderation: Intimacy*Coping | .005 | .014 | .711 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction With Family | -.621 | .141 | <.001 |

| Coping | .099 | .039 | <.001 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with family*Coping | .007 | .01 | <.001 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Social Activities | -.252 | .151 | .096 |

| Coping | .085 | .048 | .074 |

| Moderation: Social Activities*Coping | .003 | .012 | .808 |

| Independent Variable: Cynicism | |||

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction with Friends | .092 | .145 | .523 |

| Coping | .037 | .042 | .372 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with friends*Coping | -.018 | .008 | .077 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Intimacy | .216 | .144 | .134 |

| Coping | .046 | .433 | .286 |

| Moderation: Intimacy*Coping | -.011 | .01 | .261 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction With Family | -.6149 | .13 | <.001 |

| Coping | .68 | .036 | .062 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with family*Coping | .01 | .009 | .26 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Social Activities | -.31 | .131 | <.05 |

| Coping | .052 | .044 | .24 |

| Moderation: Social Activities*Coping | .011 | .012 | .376 |

| Independent Variable: Professional efficacy | |||

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction with Friends | .258 | .189 | .173 |

| Coping | .031 | .059 | .595 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with friends*Coping | -.004 | .019 | .804 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Intimacy | .003 | .216 | .988 |

| Coping | .049 | .059 | .4 |

| Moderation: Intimacy*Coping | -.018 | .024 | .455 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Satisfaction with family | .404 | .169 | <.05 |

| Coping | .038 | .06 | .52 |

| Moderation: Satisfaction with family*Coping | -.002 | .014 | .89 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Social Activities | .074 | .188 | .693 |

| Coping | .048 | .061 | .424 |

| Moderation: Social Activities*Coping | -8.31E-04 | .017 | .962 |

Table presenting the 12 moderation models, where only results where p<. 05 are considered statistically relevant.

Satisfaction with family was a statistically significant predictor of cynicism, regardless of coping strategy used [F (3, 168) = 8.473,p < .001; r 2 = .131], (Table 5). Lower Satisfaction with family scores predicts lower cynicism scores, but coping is not able to moderate this impact (B = -0.615). The same is true for social activities, which was identified as a statistically significant predictor, negatively impacting (B = -.327; p < .05), but not moderated by coping (Table 5).

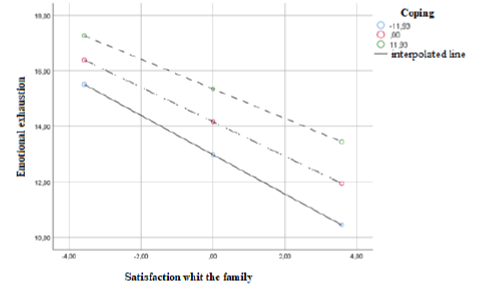

Levels of this variable are positively impacted by levels of satisfaction with family (B = .404; p < .05), but not moderated by coping strategies [F (3, 168) = 2.129,p < .098; r 2 = .037]. Satisfaction with family scores was the only dimension able to predict emotional exhaustion scores statistically significantly [F (3, 201752) = 9184.986, p < .001; r 2 = .12], with coping levels moderating this impact (Table 4). Higher levels of satisfaction with family impact lower levels of emotional exhaustion, with the lower the level of coping the greater this impact (BCope-1DP = -.708, B Cope0 = -.621, B Cope +1DP = - .534).

Finally, a final analysis was performed by means of Pearson's correlation to understand the correlation of coping with the other variables of the study. However, it was decided to analyze only the correlations obtained with the emotional exhaustion dimension for presenting the most relevant results. Statistically presented as: Self-blaming (r = .290, p<.001); Substance Use (r = .241, p<.01); Instrumental Support (r = .206, p<.01) and Positive Reinterpretation (r =.197, p<.01).

Discussions

The main objective of this study was to verify the prevalence of academic burnout syndrome and the possible correlations between its dimensions (emotional exhaustion, professional efficacy, and cynicism) with coping strategies and social support in higher education students from different health courses. The study aims to evaluate the quality of students perceived social support and its influence on the dimensions of academic burnout. It also aims to verify the associations between the coping strategies used and the dimensions of academic burnout, as well as to verify the influence of perceived social support and coping strategies as predictive variables in the development of academic burnout.

After the analysis, it was possible to notice that among the three burnout dimensions analyzed in the MBI-SS, the dimension with the highest mean score was emotional exhaustion. Thus, corroborating the results of other research conducted in recent years involving academic burnout. Studies with veterinary medicine and medicine academics showed, in their majority, high scores of emotional exhaustions (Amor, Baños, & Sentí, 2020; Puertas-Neyra et al., 2020).

The results presented in the dimension of cynicism indicate low levels of cynicism in the participating students, in line with studies conducted with health course students, in which the results show that most students have low levels of cynicism (Amor et al., 2020; Carlotto et al., 2009; Puertas-Neyra et al., 2020;).

Regarding the mean score of professional efficacies, this shows an increase, something positive, since high scores of professional efficacies are understood as a protective factor against burnout, because the relationship is inversely proportional, the higher the score of professional efficacies, the lower the risks offered by this dimension (Carlotto et al., 2009; Kilic, Nasello, Melchior, & Triffaux, 2021).

According to the results obtained in the Brief Cope instrument, it is important to mention the fact that the strategy most used by students in the sample was the use of substances, a result that contrasts with the studies of Carlotto et al. (2009) and Hirsch et al. (2015), in which this strategy was among the least used by the samples. In addition, it was observed that except for active coping, all the styles listed are emotion-focused coping styles, in which the person seeks to move away from the problem to regulate the unpleasant sensations and emotions arising from it.

In the review conducted by Andrade et al. (2021) aiming to gather studies about substance use associated with academic burnout syndrome, it identified a variation between 15.1% and 68.2% in the consumption of alcohol by students and from 9.2% to 41.4% in the consumption of illicit substances, also finding relationships between the consumption of alcohol and other illicit substances and the dimensions of academic burnout. Thus, although the cited study does not present substance use as a coping style, it shows associations between it and academic burnout.

Finally, the SSSS results obtained about social support satisfaction indicate that the dimensions of satisfaction with family and social activities had the lowest mean scores, compared to satisfaction with friendship and intimacy, a fact that contrasts with the study conducted by Almeida et al. (2018) with nursing students who showed high levels of satisfaction with social support in general. Furthermore, social support appears as a mitigator of stressful situations, thus, it acts as a protective and relieving agent of emotional exhaustion, through the use and satisfaction of resources from the available support network (Ye, Huang, & Liu, 2021).

Regarding the sociodemographic variables, the same, as observed in the study conducted by Amor et al. (2020), did not influence significant relationships in the prevalence of burnout syndrome. Differently from what was obtained in research such as that of Carlotto et al. (2006), in which variables such as year of graduation, first choice, age, previous graduation, and currently working influenced the scores obtained in each dimension of burnout syndrome. Such variables can be considered risk factors because they add demands, in addition to academic ones, to students, requiring a greater adjustment of coping strategies and personal organization to face them (Barrat et al., 2021).

In the study conducted by Kilic et al. (2021), factors such as gender and year of graduation are presented as variables in the prevalence of the dimensions of the syndrome, therefore, in general, women manifest greater emotional exhaustion while men manifest greater depersonalization, in addition, students in the last year of graduation tend to present higher rates of burnout, a fact not evidenced in the present sample.

Moreover, the course being taken did not show relevant data regarding the prevalence of burnout. According to research by Corredor and Sanchez (2020) and Almeida et al. (2018), the syndrome was more observed in the nursing area, due to the greater proximity to human suffering and work overload; however, this was not observed in the present sample because it was substantially composed of psychology students, as well as in the study by Carlotto et al. (2009), also conducted with psychology students, in which the sample did not show burnout, obtaining higher scores in emotional exhaustion and professional efficacy (the latter considered positive) and low scores in cynicism, results which are similar to those of the present sample.

In relation to the moderation analyses, it is important to highlight the role of satisfaction with social activities that impact the cynicism dimension in an inversely proportional way, that is, the higher the level of social activities, the lower the level of cynicism. This effect is like that shown in the study by Kong et al. (2022), where evidence was found that physical and leisure activities can reduce burnout levels in nursing students, also finding a negative association between physical activity and burnout. The relationship between physical activity and burnout contradicts the study by Amor et al. (2020), in which no relevant interactions were found between the practice of social activities and improvement in burnout rates in medical students investigated by the sample.

High scores of satisfaction with the family positively impact professional efficacy in such a way that even though there is again no relation with residing or not with the family there is the impact of family support as a protective factor to burnout in the dimension of professional efficacy, a fact that elucidates the importance of family support during the graduation process as well as observed by Hirsch et al. (2015) in which the family constituted itself as the main source of supporters of the analyzed nursing students. The study conducted with 188 medical students at a Croatian university demonstrated that for this group family loneliness had a negative impact on professional efficacy (Gradiski et al. 2022), highlighting the importance of family satisfaction for this dimension.

Despite being moderated by satisfaction with the family, the burnout dimensions did not suffer the effect of intervention by the sociodemographic variable related to living or not living with the family. This finding corroborates the result presented in the study by Amor et al. (2020), in which the variable living or not living with the family had no influence on the incidence of burnout of medical students who participated in the study.

Another important fact to be analyzed is the moderation effect caused by the variable coping in the emotional exhaustion dimension, as previously mentioned, this dimension has an intermediate score indicating the presence of emotional exhaustion in the sample, this effect can be attributed to the use of coping styles focused on emotion, where the goal is the relief of unpleasant feelings and emotions from the stressor, so that the coping styles most used by the sample participants; substance use, self-blame, focus on the expression of emotions, denial, and behavioral disconnection, seek to distance themselves from the stressful events for the relief of these sensations.

The overuse of emotion-focused strategies can trigger the development of emotional exhaustion since they imply a constant escape from reality. That said, the high emotional exhaustion scores corroborate the research of Carlotto et al. (2009), Hirsch et al. (2015), and Andrade et al. (2021) in which students who used emotion-focused coping strategies more frequently had higher levels of emotional exhaustion. Thus, satisfaction with family, acts to reduce the indices of emotional exhaustion, even with the use of emotion-focused coping.

Individuals who use coping strategies in general, in a larger or smaller quantity, are prone to develop elevated levels of emotional exhaustion, however, family support can reduce these effects even in individuals who make great use of coping strategies, which present higher levels of exhaustion. Thus, the greater the perception of satisfaction with the family, the lower the levels of exhaustion (Figure 1).

In relation to the results obtained in Pearson's correlation, the strategies of the emotion-focused type were more used, which aim to reduce the negative emotions and feelings caused by the stressor. The strategy of self-blame was in evidence, which consists in the act of taking responsibility for the event. The next most used strategy is substance use, which is related to the increase in emotional exhaustion, as it is a strategy to distance oneself from the stressor (Andrade et al. 2021). Still as a coping strategy focused on emotion, positive reinterpretation is used to control or reduce the existing discomfort, thus requiring a great mental engagement and thus, it is negatively associated with emotional exhaustion and positively with professional effectiveness (Carlotto et al., 2009).

The limitations of this study focus on the number and little variability of participants in the sample, which were students of a psychology course from private universities. The sample showed high rates of emotional exhaustion, but it was not possible to observe prevalence of Burnout syndrome. Important data were found about satisfaction with the family as a predictor for emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and professional effectiveness, as well as important correlations between emotion-focused coping and emotional exhaustion dimension.

It is important to emphasize the finding that the coping strategy most used by the sample was the use of substances with significant correlations in Pearson's analysis and the use of emotion-focused coping in general, being the type of coping most used by the sample, a fact that implies the high scores of emotional exhaustion, since the excessive use of emotion-focused coping contributes to the development of emotional exhaustion. Thus, this study can serve as a starting point for future research seeking to understand the reasons that lead the academic population of health students to use coping strategies focused on emotion and especially the use of substances, and projects can also be developed to help these young people to seek alternative ways of dealing with these stressors by also offering a support network for students. Research that verifies the efficacy of intervention proposals with college students that favor the development of healthier and more adaptive coping strategies can also be envisioned, as well as further research to understand the correlations between social support and burnout, especially the correlations between family support and burnout.