INTRODUCTION

Fishery resources are an important source of macro- and micronutrients for human populations, representing more than 17% of animal protein of the global consumption, and up to 50% in some countries (Thilsted et al. 2014). In Latin America, fisheries and aquaculture production are fundamental milestones in social, economic, and nutritional development, with about 85% of production resulting from artisanal fisheries (FAO & ECLAC, 2020).

This nutritional dependence on fish resources also leads to a potential exposure of human communities to health risks, considering that many of the parasitic infections that affect fish species for consumption are zoonotic (Chai et al. 2005). These parasitic zoonoses transmitted through food consumption, including fish, are of high relevance to public health and socio-economic problematics in some countries, particularly in Asia (Lima dos Santos & Howgate, 2011), in addition to being a key contributor to the transmission of diseases through food webs.

Zoonotic helminthiases related to the consumption of fish or fish products have been associated with populations in low- and middle-income countries (Chai et al. 2005). In the context of countries such as Colombia, Mexico and Peru, the acquisition of fish in local markets or through subsistence fishing can expose people to parasites at different stages of development (Rojas Sánchez et al. 2014; Castellanos-Garzón et al. 2019; Murrieta Morey et al. 2022). However, the geographic distribution of these diseases and the populations at risk have been constantly growing as a consequence of the expansion of international markets and demographic changes, increasing the risk of contagion even in developed countries (Chai et al. 2005).

Considering the above, the identification of parasites in fish not only allows us to know their diversity and ecology (Bautista-Hernández et al. 2015) but also to understand their role as keystone species in shaping communities and their importance in various ecological processes (Frainer et al. 2018). In addition, this understanding may be crucial for suggesting animal health guidelines aimed at controlling and preventing parasitic infections with health implications for both fish and humans (Quijada et al. 2005; Soler-Jiménez et al. 2017).

The yellow mojarra Caquetaia kraussii (Steindachner, 1878) (Pisces: Cichlidae) is a fish native from Colombia and Venezuela. In Colombia it is distributed in the basins of the Magdalena, Cauca, and Caribbean (Do Nascimiento et al. 2017) and Pacifica regions (Rivas-Lara & Gómez-Vanega, 2017). This fish is an important food source, being regularly consumed and traded by local communities. The research related to the mojarra amarilla includes biological and fishing aspects (Solano-Peña et al. 2013; Durán et al. 2014; Rivas-Lara & Gómez-Vanega, 2017; Zapata-Londoño et al. 2020), as well as parasitological studies (Olivero-Verbel et al. 2012; Castellanos-Garzón et al. 2020). However, these works focus on nematodes, overlooking the diversity of trematodes and associated acanthocephalans.

Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide an initial record of the diversity of helminths associated with yellow mojarra in a nature reserve in the Colombian Caribbean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

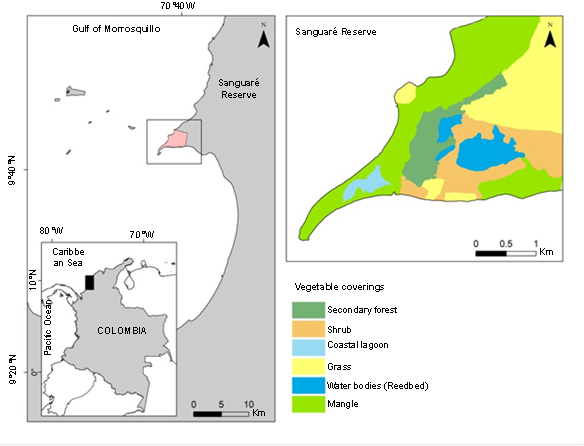

Area of study. The study was conducted in the Sanguaré Natural Reserve, located north of the Gulf of Morrosquillo 9°43'13.61" N, 75°40'33.31" W, municipality of San Onofre, Sucre, Colombia (Figure 1). The area corresponds to a civil society reserve and has an area of 898 ha and covers an altitudinal range between 0 and 50 m. The ecosystem is categorized as a tropical dry forest, exhibits a bimodal rainfall regime (April-May and October-November), an annual rainfall of 1100 mm, relative humidity close to 86% and an average temperature of 27 °C (Pizano & García 2014). Sanguaré offers a variety of vegetation cover, including 80ha of flood zones with abundant bulrushes and coastal lagoons, 110 ha of secondary forest, and 708 ha of grasslands, shrubs, and mangroves.

Figure 1 Yellow mojarra Caquetaia kraussii sampling site in the Sanguaré Natural Reserve, San Onofre, Sucre

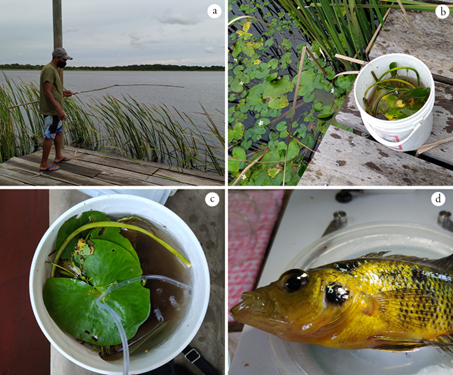

Sample collection and identification. The C. kraussii specimens were caught in the main inlet of the reserve by artisanal hook-and-line fishing in February and December 2020 (Figure 2 a) . After capture, the specimens were placed in containers with water and vegetation and transferred alive to the field laboratory, where they remained in a cool place with a constant supply of oxygen (aquarium air motor) (Figures 2b and c). For helminthological examination each fish was sacrificed by overdosing with Isoeugenol (Erikson, 2011), subsequently their total length (TL) was measured. External inspection of the eyes, oral cavity, gills, surface, and fins was carried out, as well as internal evaluation of the vitreous humor, retina, mesentery, digestive system, and body fin muscles, all by observation through a stereomicroscope.

Figure 2 Photographic summary of the collection and processing of yellow mojarra Caquetaia kraussii to search for helminths. a) Artisanal fishing with hooks, b) Containers with water and vegetation for the transfer of live fish, c) Installation of an oxygen net for host survival, d) Slaughter and immediate analysis for the recovery of live parasites.

The procedure for handling and treatment of helminths depended on their stage of development and body location. The parasite forms found were separated, cleaned with a Pasteur pipette and a fine brush, counted, and preserved in 96% ethyl alcohol for molecular analysis or AFA solution (pre-warmed in a water bath) for morphological identification. Metacercariae extracted from the buccal cavity and fins were manually dehisced, washed, counted, and fixed. Metacercariae not encysted in the vitreous humor were immediately transferred to fixatives (96% ethyl alcohol or AFA) and cleaned 24 hours after fixation. Helminths in the digestive system were transferred to a Petri dish with saline solution (0.7%), cleaned, counted, and fixed. Finally, large trematodes found in the buccal cavity and selected for morphological analysis were flattened between two slides with saline solution and then fixed. All collected specimens were transferred to the Helminthology Laboratory of PECET (Universidad de Antioquia) for taxonomic identification.

Representative specimens of each morphotype were processed (staining and mounting on permanent plates) for morphological studies following standardized protocols for helminths (Vélez, 1987; Lenis & Vélez, 2011). Specimens were identified to family or genus level (according to their developmental stage (larva or adult) following the specialized documentation (Yamaguti, 1975; Amin, 2002; Gibson et al. 2002; Pinacho-Pinacho et al. 2018; Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022) and deposited in the Colombian Helminth Collection of the Universidad de Antioquia (CCH.116 Batch 179-185). For each of the identified taxa, prevalence (P= number of parasitized hosts/number of hosts examined x 100) and average abundance (total number of parasites recovered from the host divided by the number of hosts inspected) were estimated as infection parameters (Bush et al. 1997; Bautista-Hernández et al. 2015).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

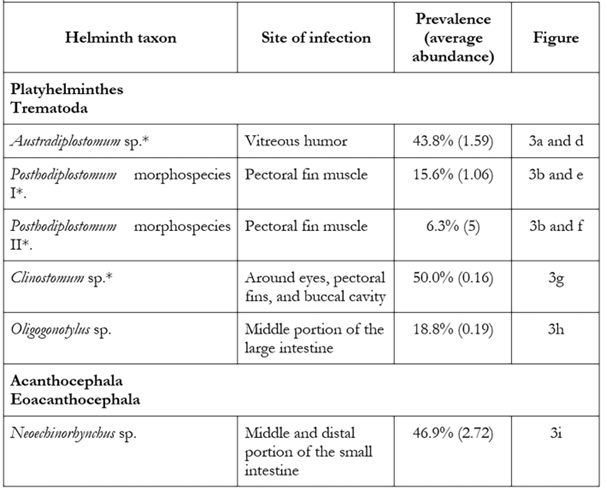

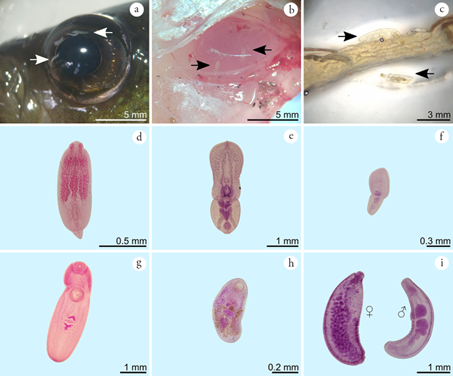

Thirty-two yellow mojarras with a body size range of 15-18 cm were analyzed. The average processing time spent on each host was 2.5 h. From the inspection of the hosts, a total of 242 parasites assigned to six types of helminths were collected, five belonging to the class Trematoda (Platyhelminthes) including Austrodiplostomum sp., Clinostomum sp., Oligogonotylus andinus (Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022), and two morphospecies of the genus Posthodiplostomum in addition to an Acanthocephala of the class Eoacanthocephala (Acanthocephala): Neoechinorhynchus sp. (Table 1). Parasites were collected as metacercariae around the eyes, outer part, and muscles of the pectoral fins, in the oral cavity and in the vitreous humor, while adult forms were found exclusively in the intestine (Figure 3 and Table 1). A total of 78.4 % of the fish examined were infected by at least one of the above taxa. The taxa Austrodiplostomum sp., Clinostomum sp. and Neoechinorhynchus sp. recorded the highest prevalences and average abundances (Table 1).

Table 1 Helminths registered in yellow mojarra Caquetaia kraussii in a coastal lagoon ecosystem, Sanguaré Natural Reserve, Sucre, Colombia.

*Genus for which only metacercariae were recovered

Figure 3 Helminths associated with yellow mojarra Caquetaia kraussii in the main reedbed of the Sanguaré Natural Reserve, Sucre. a) Free metacercariae in vitreous humor, b) Encysting metacercariae in pectoral fin muscle, c) Acanthocephalans in the middle portion of the small intestine, d) Metacercariae of Austrodiplostomum sp. e) Metacercaria of Posthodiplostomum morphospecies I, f) Metacercaria of Posthodiplostomum morphospecies II, g) Metacercaria of Clinostomum sp., h) Oligogonotylus andinus, i) Neoechinorhynchus sp. adults.

The identification of four types of metacercariae and two species in the adult stage suggests that yellow mojarra simultaneously serve as intermediate and definitive hosts for helminths. The life cycles recorded in the literature for the parasites identified here provide information on the trophic position occupied by the yellow mojarra in the ecosystem. As an intermediate host, it harbors trematodes of the genera Clinostomum, Posthodiplostomum and Austrodiplostomum, which complete their life cycle in other piscivorous species present in the reedbed. As a definitive host it harbors the trematode Oligogonotylus andinus and the acanthocephalan Neoechinorhynchus sp. which use other fish and arthropods as intermediate hosts, respectively (Razo-Mendivil et al. 2008; Lourenço et al. 2018; Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022).

The infection parameters obtained indicate that Clinostomum, Neoechinorhynchus and Austrodiplostomum are the most prevalent forms in the system studied and provide data on the parasite load for the host in the wild. In the context of local production and consumption, this information is important as a reference to make comparisons with artificial fish farming systems, especially in low-tech fish farms that are supplied by natural tributaries and favor the establishment of hosts and helminths (Lima dos Santos & Howgate, 2011).

The parasite with the highest prevalence was Clinostomum (Figure 3g), which was present in 50% of the hosts analyzed. Adults of this genus generally invade the oral cavity, pharynx, or esophagus of piscivorous birds, while several species of fish and amphibians act as second intermediate hosts (Montes et al. 2021).

The genus Clinostomum comprises 23 validated species of which 11 are found in the New World, four of which are distributed in South America: C. detruncatum (Braun, 1899), C. heluans (Braun, 1899), C. marginatum (Rudolphi, 1819) Braun, 1901), and C. fergalliarii (Montes, Barneche, Pagano, Ferrari, Martorelli, & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2021); five in Central America: C. tataxumui (Sereno-Uribe, Pinacho-Pinacho, García-Varela & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2013), C. arquus (Sereno-Uribe, García-Varela, Pinacho-Pinacho & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2018), C. caffarae (Sereno-Uribe, García-Varela, Pinacho-Pinacho & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2018), C. cichlidorum (Sereno-Uribe, García-Varela, Pinacho-Pinacho & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2018), and C. heluans (Braun, 1899), and four in North America: C. attenuatum (Cort, 1913), C. album (Rosser, Alberson, Woodyard, Cunningham, Pote & Griffin, 2017), C. poteae (Rosser, Baumgartner, Alberson, Noto, Woodyard, King, Wise & Griffin, 2018), and C. marginatum (Montes, Barneche, Pagano, Ferrari, Martorelli, & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2021).

The species C. marginatum and C. complanatum (Rudolphi, 1814) Braun, 1899) were reported from piscivorous birds in the Colombian Caribbean (Rietschel & Werding, 1978; Fernandes et al. 2015). However, Caffara et al. (2011) indicate that C. complanatum has a distribution restricted to the European continent, suggesting the need for a taxonomic revision of the populations of Clinostomum reported in Colombia.

Clinostomiasis is a disease of minimal importance at the fish farming level, but Rosser et al. (2018) reported serious infections that can affect the health and subsequent marketability of fish. Metacercariae give fish a bad appearance, so people involved in sport, artisanal and commercial fishing discard parasitized individuals (Rodríguez et al. 2001). Clinostomum infections have been reported in humans, with localization in the mucosa of the throat and eyes. In cases in which a human consumes raw fish, the parasite accidentally attaches to the mucosal surface of the throat, resulting in a clinical syndrome known as halzoun, which manifests with symptoms of laryngopharyngitis (Park et al. 2009). This zoonosis has been reported mainly in countries such as Japan and Korea (Hara et al. 2014). When the infection is located in the lacrimal opening it manifests with discomfort and pain in the frontal sinus area (Tiewchaloern et al. 1999).

Neoechinorhynchus sp. was the form with the highest average abundance and the second most prevalent with 46.9% in C. kraussii (Figures 3c and 3i). This genus represents a diverse group of endoparasites of freshwater fish and turtles, with approximately 116 described species (Pinacho-Pinacho et al. 2018). The study of different populations of Neoechinorhynchus in Central America has allowed the validation of eight species in fish (Pinacho-Pinacho et al. 2020): N. golvani (Salgado-Maldonado, 1978), N. chimalapasensis (Salgado-Maldonado, 2010), N. roseum (Salgado-Maldonado, 1978), N. brentnickoli (Monks, Pulido-Flores & Violante-Gonzalez, 2011), N. mamesi (Pinacho-Pinacho, Pérez-Ponce de León & García-Varela, 2012), N. panucensis (Salgado-Maldonado, 2013), N. mexicoensis (Pinacho-Pinacho, Sereno-Uribe & García-Varela, 2014), and N. costarricense (Pinacho-Pinacho, Sereno-Uribe, García-Varela, & Pérez-Ponce de León, 2020). In South America, 12 species of Neoechinorhynchus have been described in fish (Arredondo & Gil de Pertierra, 2012; Melo et al. 2013; Brito-Porto et al. 2017; De Souza & De O. Malta, 2019): N. macronucleatus (Machado, 1954), N. butternae (Golvan, 1956), N. paraguayensis (Machado, 1959), N. prochilodorum (Nickol & Thatcher, 1971), N. curemai (Noronha, 1973), N. pterodoridis (Thatcher, 1981), N. villoldoi (Vizcaino, 1992), N. pimelodi (Brasil-Sato & Pavanelli, 1998), N. veropesoi (Melo, Costa, Giese, Gardner & Santos, 2013), N. inermis (Brito-Porto, Silva-de Souza & de Oliveira-Malta 2017), N. pellonis (De Souza & De O. Malta, 2019), and N. colastinense (Arredondo & Gil de Pertierra, 2012).

In Colombia, the study of acanthocephalans is still in its early stages, and only five species are reported in fish (Nickol & Thatcher, 1971; Schmidt & Hugghins, 1973). Two of these belong to the genus Neoechinorhynchus: N. prochilodorum (Nickol & Thatcher, 1971) reported on Prochilodus reticulatus (Valenciennes, 1850) in Laguna del Sonso, Valle del Cauca (Nickol & Thatcher, 1971), and N. buttnerae (Golvan, 1956) reported on Colossoma nigripinnis (Cope, 1878) in Leticia, Amazonas (Schmidt & Hugghins, 1973). Considering the high levels of cryptic diversity that this group presents in other regions of the Neotropics (Pinacho-Pinacho et al. 2018), Neoechinorhynchus species richness may be underestimated for the country. Based on this scenario, the morphospecies reported here could represent the record of a species previously unreported for Colombia. Taxonomic studies will allow us to know the specific identity of this morphospecies and its relationship with other species of the genus.

Acanthocephalosis, including that caused by forms of Neoechinorhynchus, has negative impacts on fish production. Neoechinorhynchus buttnerae is considered one of the species with the greatest impact on aquaculture production (Ramos Valladão et al. 2020). It is considered a silent disease, which goes unnoticed by the fish farmer, if adequate sanitary control is not carried out (Ramos Valladão et al. 2020). Acanthocephalans affect the mucosal, submucosal, and muscular layers, causing laceration and intense inflammatory reactions. The main clinical manifestation in fish parasitized by acanthocephalans is progressive weight loss. Once in the intestine of the fish, the parasite alters the integrity of the intestinal mucosa and then begins to compete for the nutrients ingested by the fish (Jerônimo et al. 2017).

In the present study, three morphospecies of the family Diplostomidae were also found parasitizing C. kraussii, these were Austrodiplostomum sp. in vitreous humor (prevalence 43.8%; Figures. 3a and 3d) and two morphospecies of Posthodiplostomum encysted in pectoral fin muscles (prevalences of 15.6% and 6.3%; Figures. 3b, 3e and 3f). Adult forms of Austrodiplostomum are intestinal parasites of cormorants, while metacercariae are parasites of the eyeball and brain of freshwater and brackish water fish (García-Varela et al. 2016; Sereno-Uribe et al. 2019). This genus includes only two species: A. mordax (Szidat & Nani, 1951), described in South America and A. compactum (Lutz, 1928) reported from the United States, Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Peru, and Brazil (De Fátima Cracco et al. 2022). In the Colombian Caribbean, adults of A. compactum and A. ostrowskiae have been reported in piscivorous birds (Rietschel & Werding, 1978) and as metacercariae in C. kraussii (Olivero-Verbel et al. 2012) in Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852) and O. niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Soler-Jiménez et al. 2017). It is important to note that recent molecular analyses propose synonymy between A. compactum and A. ostrowskiae (García-Varela et al. 2016; Ostrowski de Núñez, 2017; De Fátima Cracco et al. 2022). Austrodiplostomum metacercariae cause verminous cataracts in fish and can affect other organs such as gills, muscle, swim bladder and brain (Amin, 2002). High infections in cultures associated with this genus are attributed to high fish densities and abundance of mollusk hosts in artificial ponds (Violante-González et al. 2009).

Posthodiplostomum are intestinal parasites of piscivorous birds with a worldwide distribution. The metacercariae of Posthodiplostomum found in the present study correspond to two morphospecies (Figures 3e and 3f), which differ from each other in body size and organ distribution. Eight species are reported from South America: Posthodiplostomum grande (Diesing, 1850), P. macrocotyle (Dubois, 1937), P. microsicya (Dubois, 1937), P. nanum (Dubois, 1937), P. obesum (Lutz, 1928), P. giganteum (Dubois, 1988), P. mignum (Boero, Led & Brandetti, 1972), and P. eurypygae (Achatz, Chermak, Bell, Fecchio & Tkach, 2021) (Fernandes et al. 2015; López-Hernández et al. 2018). In Colombia, the presence of P. nanum is recognized in Butorides virescens maculata (Drago & Lunaschi, 2011), and although previous work considered the occurrence of P. minimum (Rietschel & Werding, 1978), this has not been validated in recent listings for South America (Fernandes et al. 2015). The high morphological and molecular variation reported in metacercariae of some species of the genus in Central America (Perez-Ponce de León et al. 2021; Díaz Pernett et al. 2022) highlights the importance of carrying out taxonomic studies of the morphospecies found here, in order to establish their relationship with previously described lineages.

Metacercariae parasitize the surface of the body, fins, scales or in the musculature and body cavity of fish (Ritossa et al. 2013; Cech et al. 2020). When the parasites are located in the skin, melanophores agglomerate around them, giving rise to dark pigmented spots, which is known in fish farming as black spot disease (Rodríguez et al. 2001). Other liver-hosting Posthodiplostomum species are associated with liver damage that can cause digestion dysfunction and consequently, malnutrition in infected fish (Osorio-Sarabia et al. 1986; López-Hernández et al. 2018). Although at the fish farming level, it is known that black spot disease is produced by diplostomids (Alvarez-León, 2007 ; Horák et al. 2014), taxonomic studies are required to determine the species existing in Colombia.

Adult forms of Oligogonotylus andinus (Figure 3h) recorded a prevalence of 18.8 % and the lowest average abundance in the study. This is a genus exclusive to cichlids and contains three species, O. manteri (Watson, 1976) and O. mayae (Razo-Mendivil et al. 2008) in Central America (Razo-Mendivil et al. 2008) and O. andinus (Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022) described in the blue mojarra (Andinoacara latifrons) in a fish farm of peasant economy in the Antioquia department. The life cycle of O. andinus is complex and involves cochliopid, poeciliid and cichlid micromollusks (Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022). This research reports for the second time a population of O. andinus in Colombia, extending its distribution range from the Cauca River basin in the Andean region to the coastal region of the Colombian Caribbean.

The infection parameters in this study for O. andinus in yellow mojarra contrast with those found in blue mojarra, where the abundance and prevalence values reach values of 100% and 39.3% (Vélez-Sampedro et al. 2022). Focus studies on small fish farming systems provide important data on the dynamics of parasite transmission, useful for the design of control programs. The study of the life cycle of Oligogonotylus in blue mojarra revealed that the presence and high densities of intermediate hosts in fishponds favor high parasite loads (re-infection) in definitive hosts.

Therefore, given the importance of the mojarra amarilla in the food security of local communities, it is recommended to continue with efforts to identify the associated helminths and their transmission routes, which will not only strengthen programs for the management and control of diseases caused by helminths, but also public health strategies at the local level, as well as promote new studies to define the impact of parasites at the fish farming level.

At the taxonomic level, an integrative approach is required that includes obtaining adult specimens for morphological characterization of each species, as well as molecular validation of the parasite species found here and reported from metacercariae. In addition, the molecular approach will allow the identification of cryptic species such as the genus Neoechinorhynchus.

At the ecological level, the identification of other hosts involved in the life cycle of the parasites and their mode of transmission to fish is necessary.

Finally, from a veterinary perspective, treatment and control schemes should be developed. It is hoped that this study will serve as the foundation for future research, enabling diagnosis for other species of fish consumed in the region.