Introduction

Communication plays a significant role in a language classroom. As a result, teachers and researchers have developed various methodologies and approaches to help learners improve their communication skills. One such approach is Task-Based Instruction (TBI) which, according to Ellis (2003), aims to create tasks that enable students to communicate effectively in different contexts while understanding cultural values. Hence, there is a strong connection between communicative competence and TBI. Lin and Wu (2012), as cited in Pohan (2016), note that TBI has been adopted in countries such as Taiwan, China, Indonesia as part of their educational policies to enhance the communicative competence of both students and teachers.

In Colombia, there has been a notable effort to adopt and adapt TBI and other approaches to improve communicative competence in language classes, as evidenced by the works of Cordoba (2016) , Calvache (2017) , and others. Indeed, the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) in the years 2006, 2014, and 2016 has developed important guidelines that each regional government has adapted to their respective contexts. These guidelines include the English Suggested Curriculum, The Basic Learning Rights, and Basic Standards of Competence. TBI is one of the primary approaches recommended by the MEN to enhance communicative competence in the English language by including tasks that are aligned to the Colombian context.

To implement the MEN’s guidelines, the Department of Risaralda in Colombia has launched various bilingualism initiatives, including Bilingual Risaralda and the Systematization Process of Meaningful English Teaching Experiences in Risaralda (López & Velásquez, 2021), which is guided by the Secretary of Education and seeks to improve the English language level in Risaralda. The most recent bilingualism macro-project involved 33 public schools distributed across the Department. This project was conducted in alliance with the academic team of the BA in Bilingualism and the Institute of Foreign Languages of the Technological University of Pereira (UTP)1. The objective was to strengthen the English competence of the students and teachers by incorporating the bilingualism guidelines provided by the MEN (2016) English Suggested Curriculum and to contribute to the development of communicative competence through the inclusion of the TBI approach.

To accomplish the main objectives of the macro-project, teachers received training on implementing Task-Based Instruction (TBI). The training consisted of fourteen sessions held between 2018 and 2019 in which twelve English language teachers from the 12 municipalities of Risaralda volunteered to participate. During the training seasons, English language teachers worked closely with UTP’s academic team to design TBI learning guides that included tasks tailored specifically for middle grades (6-8) and high grades (9-11). The tasks were developed with consideration for the context, interests, and needs of Risaralda’s students.

To create these learning guides, teachers worked in pairs to brainstorm task ideas that were relevant to the Colombian context. They also included communicative competence objectives and suggested materials. The UTP academic team then completed the guide design by adding more sequences of activities, materials, and assessment procedures. The final product was shared with the twelve teachers, who provided feedback and made final decisions. To explore the experiences of the English language teachers with the implementation of the learning guides, the following research question was posed: What are the perceptions of English language teachers regarding Task-Based Instruction in Risaralda, Colombia?

The current trends in bilingualism advocate for a shift in the teaching paradigm (Mejia, 2006). This paper sets a precedent for the strategies adopted by Department of Risaralda has adopted and adapted to promote bilingualism in the region and strengthen the English proficiency levels among its population, particularly through the implementation of English classes based on TBI adapted to the students’ contexts. Additionally, this paper sheds light on how English language teachers can continue working on their professional development by participating in projects like this one developed in Risaralda.

Theoretical Framework

This section describes the theoretical foundations that support this study. The concept of communicative competence is presented based on Hymes, as cited in Torres (2019). TBI and tasks follow the definitions proposed by Ellis (2003) , Nunan (2004) Cordoba (2016) , and Calvache (2017) . Finally, teachers’ perceptions are described as defined by Reyes and Cruz (2017), Carvajal and Duarte (2019) .

Communicative competence

To understand the purpose of the training sessions with the 12 English language teachers was to strengthen their communicative competence, it is important to define the concept. Hymes (1972) cited in Torres et al. (2019) defines communicative competence as using specific language knowledge in a truly communicative setting. Rickheit and Strohner (2008) provided another interpretation of the concept of communicative competence, which incorporates Torres et al.’s definition. This interpretation suggests that communicative competence is linked to a set of guidelines that create a smooth conversational flow, without being limited by any particular linguistic system that unifies language and its usage within a defined character. It is important to note that these conceptualizations of communicative competence also encompass sub-competencies such as linguistic, pragmatic, and sociolinguistic skills.

The Common European of Reference for Languages CEFR (2018) also defines communicative competence in the light of linguistic, sociolinguistic, and pragmatic competences. According to CEFR (2018), linguistic competence refers to the knowledge of the language system, that is grammar, vocabulary, orthography, morphology, syntax, and phonology. In contrast, sociolinguistic competence refers to “the knowledge and skills required to deal with the social dimensions of the language use” (CEFR, 2018, p. 118). In other words, it encompasses understanding the cultural aspects of language use. Pragmatic competence has to do with the communicative functions of the language in which language has to be used in an organized, coherent, and transactional way. Based on these definitions, the new bilingualism policies have incorporated communicative competence as the main pilar in English language education.

Task-Based Instruction and Tasks.

As Task-Based Instruction (TBI) aims at developing communication (Long, 2015), it is necessary to consider it as an approach that allows learners to exchange meaning. According to Willis and Willis (2011) , TBI supports the educational process by means of creating a necessity that can only be solved through the language, with tasks serving as the core component of this approach. By situating students in context, tasks generate a need that can be met through language use, leading learners to arrive at a solution.

Ellis (2003) shares similar views on TBI, highlighting that this approach utilizes daily social communicative acts of students as inputs and methods of language learning. TBI focuses on meaning, communicative strategies, and communicative effectiveness. Ellis understands that tasks are the central element of TBI:

A task is a work plan that requires learners to process language pragmatically in order to achieve an outcome that can be evaluated in terms of whether the correct or appropriate propositional content has been conveyed. To this end, it requires them to give primary attention to meaning and to make use of their own linguistic resources, although the design of the task may predispose them to choose particular forms. (Ellis, 2003, p. 16)

Cheng and Moses (2011) provide a more specific definition of tasks, which are viewed as the primary means for learning a second language. However, these authors explain that the educational benefits of tasks alone do not guarantee successful language learning. This is because the teacher, who acts as the facilitator of the task, needs to have a solid understanding of how tasks work when implementing them in the classroom. The success of a task, as Cheng and Moses sustain, depends on the teacher’s perceptions regarding TBI and the tasks themselves. If a teacher does not properly follow the process for conducting a task in classroom, students will not achieve the main objective of TBI which is communication.

The ideas by Cheng and Moses (2011) are complemented by Pohan et al., (2016), who state that that teachers’ perceptions of TBI can have either positive or negative impacts on language learning. According to Pohan et al., (2016) teachers are motivated to use TBI is to improve students’ interactive skills, intrinsic motivation, academic progress, and their own professional development. However, some teachers who are required by their schools to use TBI in their teaching express reluctance due to their lack of knowledge in implementing it, the inadequacy of materials for TBI, and difficulties in assessment.

Lin and Wu (2012), as cited in Pham and Buu (2018) , also acknowledge the potential benefits of TBI in English education as it allows students to gradually develop communication skills. Nevertheless, they point out the difficulties in implementing it due to factors such as inflexible syllabus, class size, exam-oriented systems, and limited teaching time. Similarly, Ismaili (2013) claims that TBI provides learners with opportunities to use language in relatively real-life situations. In his study, learners lacked exposure to English outside the classroom, so the implementation of tasks helped them to improve their communication skills.

Research has proven the effectiveness and positive perceptions of TBI in Colombia, despite the differences in how it is implemented in international settings. Calvache (2017) explains that TBI is an approach that enables teachers to facilitate communication classes in which learners are not simply transmitting and repeating grammar, but rather performing tasks that enable them to use meaningful and realistic language, thus raising their awareness of sociocultural differences. To explain the success of a task, Calvache (2017) cites Nunan (2004) , who emphasizes the importance of following a process that includes a pre-task stage that prepares and provides students with the necessary linguistic elements to develop the task, a while-task stage where students rehearse and present the task, and a post-task stage to allow learners to reflect and self-assess their learning process during the task.

Conversely, Córdoba (2016) centered his study on how TBI can integrate the four language skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) mediated through TBI. His findings suggested that both teachers and students perceived TBI as an opportunity to learn language in a more natural way. However, in the same line of Calvache’s (2017) conclusions, Córdoba also emphasized the importance of following the TBI framework for effective implementation, which includes the pre-task, while-task, and post-task stages.

Teachers’ perceptions

Since the goal of this study is to describe English language teachers’ perceptions regarding the implementation of TBI, it is paramount to conceptualize what perceptions are. According to Polkinghorne (1995), cited in Carvajal and Duarte (2019), perceptions are stories that describe human experiences that help understand learning experiences. For this reason, it is crucial to give voice to teachers and pre-service teachers as their narratives can contribute to reflect on their professional development (Carvajal & Duarte, 2019).

Furthermore, Pennington (2010) explains that teachers’ perceptions are centered around personal feelings, opinions, and attitudes that inspire people to take actions. In this sense, Reyes-Cruz et al. (2017) state that the word “perception” is usually associated with conceptions, beliefs, and views with regard to a particular situation or phenomenon that enables a particular community to know the way people think, thereby constructing knowledge based upon these “conceptions”.

This study agrees with the definition provided by Papadakis and Kalogiannakis (2020) who point out that teachers’ perceptions are “the thoughts or mental images which teachers have about their professional activities and their students, which are shaped by their background knowledge and life experiences and influence their professional behavior” (2020, p. 17). In this project, teachers’ perceptions are conceived as the experiences, narratives, and thoughts teachers have about the implementation of TBI.

Method

Research Design

This study was developed as a qualitative research that aims at understanding how people create the meanings of the world and their experiences (Merriam, 2009), which includes the perceptions, considerations, and narratives of the teachers about the implementation of TBI. Additionally, the study was framed within the methodology of narrative inquiry, which highlights the importance of deeply understanding people’s experiences to get a better view of the real factors that affect their performances, taking into consideration that teachers are also people feelings and experiences. (Estefan et al., 2016; Clandinin, 2013; Hutchinson, 2015).

Participants and Context

This research is part of a larger project on bilingualism that was carried out between 2018-2019 by the Gobernación de Risaralda and the Secretary of Education of Risaralda, in partnership with the Technological University of Pereira and the vice-rectory for research and extension. The macro-project involved 33 state schools, but only 12 of them decided to participate in this study. The selected schools are non-certified schools (Escuelas no Certificadas), which means that these schools do not have a Secretary of Education in their location but are instead governed by the main Secretary of Education of Risaralda.

A convenient sampling technique was used to select the English language teachers who participated in the study, meaning that only those who volunteered to participate were included (Otzen & Manterola, 2017). The Secretary of Education of Risaralda sent an invitation letter to 33 teachers who had taken part in training sessions with the UTP, and 12 of them accepted the invitation. These 33 teachers had previously been involved in the design of the learning guides that were implemented in 33 public schools in Risaralda. However, for the purposes of this study, only the data collected from the 12 participating teachers were analyzed (see Appendix D).

Research Procedures

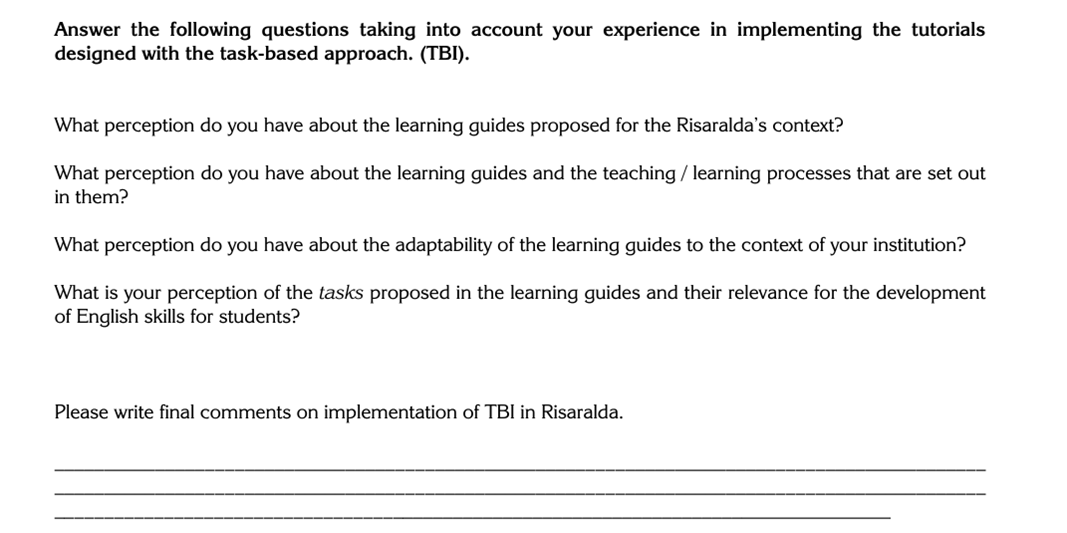

This research used three different data collection instruments to analyze English language teachers’ perceptions after the implementation of TBI. The first instrument was a questionnaire (see Appendix A) as it is a useful method for discovering participants’ narratives about a situation (O’Leary, 2014). The questionary asked four questions mainly about the teachers’ experiences implementing the tasks proposed in the learning guides designed by them, and their adaptability to Risaralda’s context.

The second instrument was classroom observations, which Marshall and Rossman (1989), cited in Kawulich (2005) , define as “the systematic description of events, behaviors, and artifacts in the social setting chosen for study” (p. 2). The observations were conducted by the academic team of the project which provided an external view of the English language teachers’ perceptions as they were not part of the research team. The academic team was composed by English language teaching professionals hired by the Gobernación de Risaralda to receive training in supporting the participant teachers in the implementation of the project. To conduct the observations, the team used a pre-established observation format (see Appendix B) that included the description of the task, the development of the task (pre-task, while-task, and post-task stages), class procedure, material used, and general comments regarding the implementation of TBI.

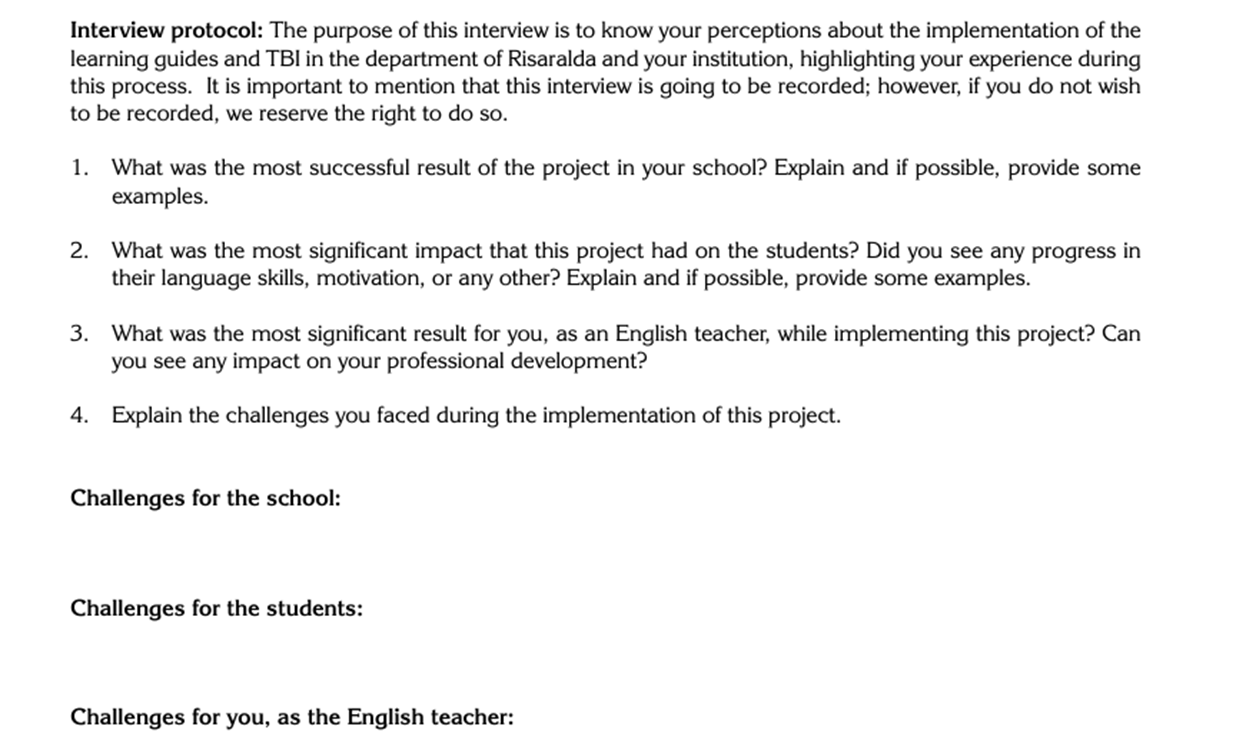

The third instrument was a semi-structured interview conducted with the twelve English language teachers at the end of the project during the last training session. Lambert and Loiselle (2007), as cited in Coughlan et al. (2009) , define the interview as a “research strategy to gather information about participants’ experiences, views, and beliefs concerning a specific research question or phenomenon of interest” (p. 309). The interview inquired about the teachers’ experiences, narratives, and perceptions of TBI and was conducted in English (see Appendix C).

Ethical Considerations

To ensure the trustworthiness of this research, an informed consent was obtained from the Gobernación of Risaralda, allowing the use of information from the project for academic purposes only. This consent contributes to the credibility of the research, as all findings are based on plausible interpretations of the original data collected by the professionals who worked with Gobernación of Risaralda.

Data Analysis

Regarding data analysis, this research used Grounded Theory proposed by Glasser and Strauss (1967) cited in Morales (2015) . This method allowed for the identification of ideas and concepts through the narratives of the participants, which were then coded based on their perceptions. The analysis process followed the steps proposed by Cresswell (2009) , which included organizing, transcribing, and digitizing the data. In this process, I received support from five students of the BA in English Language Teaching at UTP.

The next step in the data analysis process involved reading and categorizing the data into themes. Two main categories emerged: perceptions about the implementation and challenges of TBI. After naming categories, the data was re-read to interpret the main categories. Excerpts that share similar ideas were then taken and the number of occurrences repeated were counted. At the end of the data collection, the codes with a greater number of occurrences were the ones considered to interpret teachers’ perceptions and later classify them. The academic team of the BA in Bilingualism supported me in this process by assisting with the categorization of data and counting the number of occurrences of each code.

Findings

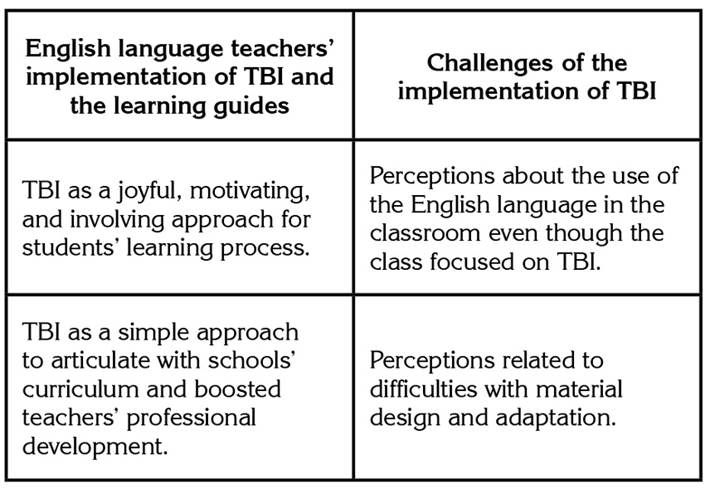

Once all data collected were analyzed, two major categories were found as shown in Table 1.

TBI as a Joyful, Motivating, and Involving Approach for Students’ Learning Process

The first perception to highlight is that English teachers perceived TBI as more engaging, joyful, and motivating for students in their learning process. According to their feedback, students seemed to be enthusiastic about using the target language in activities that were related to their daily life or contexts. Moreover, learning vocabulary and grammar was done in a more implicit way, without presenting concepts openly from the beginning of the lesson. This caught students’ attention and demanded them to search for words to communicate as the classes did not start with an explicit grammar explanation, but with a contextualization of the topic. These perceptions were consistent throughout the different data collection instruments. Teachers expressed that the learning guides implemented made the process more enjoyable for learners. As an example, the following narrative of Teacher 1, taken from the interview, illustrates this perception:

The English learning guides have been really helpful, the students have enjoyed the lessons. Students expressed that at the beginning of the project, they did not like English because it was always writing on their notebooks, but at the end of the project, they did different tasks that helped them to practice the language. For example, explaining the process of growing coffee which is very typical in this region.

The learning guides used in the classroom were based on TBI. As a result, students showed more interest in their learning process when exposed to this approach. Indeed, teachers observed a different attitude from students when learning English using tasks. Based on the narratives of the teachers in the questionnaire, teachers believed that one of the main reasons for students’ motivation in the classroom were real-life related tasks. This was stated by a Teacher 2 in the questionnaire:

The tasks have motivated the students since their contents conform to their previous or real-life knowledge.

In the previous except, it can be inferred that adjusting the learning guide’s contents to the students’ realities was a factor that enhanced their motivation towards learning. Consequently, the students’ increased motivation played a significant role in keeping them engaged in their learning processes. Furthermore, by looking at the classroom observations, motivation is still mentioned as something noticeable among the teachers involved in this project, as it is stated in the classroom observation 7 by Teacher 5:

I notice that the boys, thanks to the topics of the tasks, are very motivated to tell what they have, what they see in their community, through the tasks.

It is remarkable to mention that the learning guides included tasks related to students’ context created a better and more submerged English environment as stated by Teacher 3 in the interview:

The most relevant task my colleagues designed was when the different grades were divided into Colombian regions. Students looked for all the information considering the aspects concerning to traditions, customs, typical dancing, typical dishes, clothes. They put in together this information in a brochure and, they presented all this in the annual exposition (presentation) in the school. Students got dressed according to the region they had. They prepared the typical dish, they danced. They showed the most representative elements from each region. Students and visitors could learn more about different regions from Colombia.

The previous excerpt clearly illustrates how the learning guides were adapted to students’ Colombian context and how working with tasks motivated students to learn the language and use it not only in the classroom, but in event outside the classrooms.

The Learning Guides Facilitate the Articulation of the TBI Approach with the Schools’ Curriculum and Boosted Teachers’ Professional Development

Another perception regarding the implementation of TBI is its alignment with the needs and curriculum of the schools. The data analysis revealed that teachers perceived a prominent change in the way English was incorporated in the schools’ curriculum. For example, at the beginning of the project, most of the content presented in the curriculum and syllabi was related to the structural aspects of the language such as grammar, and vocabulary.

After implementing the project, English teachers were able to incorporate the principles of the TBI approach in the Schools’ English curriculum, which allowed them to structure their classes in a more organized way. This helped them to better understand their role, the materials they needed, and the main aims of each class. This is reflected in the following excerpt from the questionnaire written by Teacher 4:

The learning guides included all the information related to my role as a teacher: curriculum, tasks, action plans, platforms, virtual communication. Before the project, I did not consider the content proposed in the curriculum of my school because it was just grammar. After the intervention, I know how to design tasks that entail all the communicative aspects of the language.

The previous excerpt highlights the significance of compiling all the information to establish better classroom practices and notes the changes in the curriculum resulting from the implementation of TBI, which represents a paradigm shift in the schools and in the classrooms.

Another relevant aspect that illustrates the articulation of the learning guides with the school’s curriculum is related to the alignment that the learning guides had with the guidelines proposed by the Ministry of Education MEN (2016), English Suggested Curriculum, Basic Learning Rights, and Risaralda context. Teacher 6 highlighted this alignment in their interview.

The curricular implementation, in my opinion, is very consistent with the needs of the region and is very well aligned with national English policies and the documents such as the English suggested curriculum and others.

Building on the previous information, the participants of the study believed that the curricular implementation, referring to the process of teaching their classes with the TBI learning guides was aligned to the English national policies of the MEN. This alignment not only strengthened the development of the classes, but also improved schools’ curriculum. With the learning guides as tangible guidance English teachers were able to restructure the English curriculum at their schools.

In addition to the improvements in the English classes and the restructuring of school curricula, the learning guides also had a positive impact on the professional development of the English language teachers in Risaralda. Teachers reported that working with the learning guides, designed by themselves, enabled them to improve their planning skills, select materials more effectively, and develop additional activities that they were required to do but struggled to find time for. The narrative of Teacher 11 in the interview clearly illustrates the professional development growth.

In my case, it facilitates many things. Teaching in a public-school context requires not only teaching the subjects of the class but also solving problems of indiscipline, attending to parents, and doing follow up. Also, well, daily planning as sometimes you can give five or seven different courses, different grades. So, these (learning guides) give us time for other things that are equally relevant while we are in charge of other things. (We know that at the end) with these guides, we are going to have a solid product, since we have the step by step (process), if we know what we want to adapt, we have all the necessary attachments, then it is quite a complete material. And, in general terms, it fit like a glove.

The TBI learning guides helped the educator to save time in the different academic responsibilities he/she had, and as a result, the extra-time gained allowed the teacher to focus on other academic obligations as the materials were complete and ready to be adapted to the class. Additionally, working with the learning guides, based on TBI, boosted professional development in the English language teachers experiencing a methodological shift as expressed by Teacher 10 in the questionnaire:

This project made me to ‘change the chip’ concerning to strategies and methodologies. Before the training sessions, I used to guide the classes focusing on grammar and vocabulary without thinking of a context to use them. With the training sessions, I learnt to integrate grammar and vocabulary with a task including not only linguistic competence, but pragmatic and sociolinguistic competences.

Teacher’s 10 opinion goes hand in hand with what Teacher 6 expressed in the interview:

Working through this project I have experienced a really big change in the way of teaching English. Nowadays, when I teach my subject, I don’t focus on the grammar topic, because that´s something that really doesn’t make the difference in students’ learning process, it´s not meaningful for them. On the other hand, I focus on a task that really calls their attention and I teach the grammar topic implicitly, so they don´t feel like they have been learning the same thing in their whole lives.

These narratives of teachers demonstrate that the implementation of TBI allowed them to enhance their professional growth, undergo a shift in their teaching methodology, and align the TBI approach with the learning needs of their schools and students.

Challenges After the Implementation of TBI in Risaralda.

The second major finding after data analysis was teachers’ challenges during the implementation of TBI in their classes. As presented in Table I, the first challenge has to do with the use of TBI in the class, but with Spanish classroom interaction. The second was related to issues in material design and adaptation.

Perceptions About the Use of the English Language in the Classroom Even Though the Class Focused on TBI

To begin with, the data collected from the group of observers acknowledged that although teachers made use of the TBI learning guides, the percentage of English classroom interaction was lower than expected. The first of the excerpts, taken from the observation 2 of Teacher 9 shows that both teachers and learners used English sparingly.

Percentage of English used by the teacher and learners was very not enough. Even though the content of the class was presented in English, the teacher uses Spanish to give instructions, it is recommended to avoid translation and give and reinforce basic English commands.

These data indicate that the observed teacher had a very low level of English use in the classroom. According to the observer, even basic teacher’s functions, such as giving instructions, were performed in the L1. Consequently, learners’ responses were in Spanish too. Teachers serve as models for students, so if the teacher does not use the L2 for communicating, neither will the learners. Even though teachers used TBI to guide classes, it was necessary to increase the percentage and constant use of the L2, so communicative acts make more sense in the classroom. The following excerpt, taken from observation 2 of teacher 4, reinforces this issue as it states:

The class had an interesting dynamic; however, most of the instructions and class procedures were done in Spanish.

Despite the low use of English for classroom interaction, data show that during the task development, teachers followed the framework of TBI and encouraged students to use the English language, particularly in the core task stage as illustrated in the following except taken from an observation 3 of Teacher 9.

It is evident that students and teachers are using the English language during the planning and presentation of the tasks; enabling us to see students’ language progress.

The observations during the implementations of TBI were also corroborated by teachers themselves in their narratives. Teachers claimed that in most of their classes, their interactions are in Spanish as this is a way of managing the discipline of the class as stated by teacher 9 in the interview.

It is difficult to teach in public schools in which in most classes you have 35 or 40 students. Controlling discipline is a big issue, so I sometimes use Spanish to avoid classroom issues. However, with the implementation of TBI, I have noticed that my students are more motivated to learn, so I will increase more the use of English in my classes.

After analyzing the narrative of this teacher, it becomes evident that the use of Spanish during the English classes is basically to control discipline and it is not related to the implementation of the class. However, this teacher expresses that working with the TBI has enabled her/him to have better students’ disposition to the class allowing him/her to gradually increase the use of English for classroom interaction.

Through the process of the accompaniment by the group of observers, it was possible to see some progress in the use of English for classroom interaction as it is seen in observation 10 of Teacher 9:

It is noticeable that the teacher is following the recommendations proposed by the academic team of the UTP regarding the use of the English language for giving instructions, for following up activities, and for interacting with the students in class allowing students to communicate using the target language.

In conclusion, although English classroom interaction presented a challenge for the teachers, the feedback provided by the group of observers proved to be helpful in identifying areas for improvement. They helped teachers to take actions to improve in certain aspects of their classes and that impacted positively in the implementation of TBI and the development of communicative competence.

Perceptions Related to Difficulties with Material Design and Adaptation.

One of the significant challenges identified in the study was the difficulties of English teachers in using or designing material, planning the lessons, and adapting themselves to the TBI approach. Some teachers reported that they found the guides hard to understand, the guides needed to have a better adaptation to the context, such as indigenous groups who do not speak Spanish and who were learning English as a third language. Also, students with special educational needs and students with a very low English competence. Hence, it is worth mentioning the need to design culture-sensitive materials and assess their relevance in the class. The following excerpts from the questionnaire exemplifies how Teacher 12 felt about the learning guides:

Some videos are long, or their level is high, so I need to adapt the material to my students’ level and their language. In my school, I have students who belong to indigenous groups. They do not even speak Spanish well and sometimes the topics proposed in the tasks were very challenging for them.

Overall, this perception is providing information about the adaptation that is needed. The content that was created in the learning guides not all the time was accurate for the students’ proficiency. Therefore, teachers had to adapt different types of materials to make it more appropriate for the learners. A similar narrative is provided by Teacher 8 during the interview:

As a Teacher I had already used tasks for teaching. However, the implementation of the task guides provided by the project was a new challenge, as those tasks were new to me, I didn’t know how they were going to work on students. I consider that they are a great tool for me to use in English classes, as they provide me with a lot of activities for implementing in class, however I consider that I still need to continue analyzing the results of each task implemented in order to adapt it to students needs and trying to get a better result from them, let’s remember that as these tasks had never been implemented before, the results were still unknown, because some activities might not go as well as planned.

From this piece of information, it is noticeable that implementing the learning guides also involves a rigorous analysis on the teacher’s side. That is terms of the success of the task implemented and the material used which required teachers to dedicate more time. Additionally, the fact of changing from one methodology to another involved a process that was challenging as it is reflected by Teacher 6 in the questionnaire.

Before implementing the tasks, students didn’t know anything about task implementation, students were following a grammar focused approach done by the previous teacher, this made students feel confused at the moment of starting using TBI, because students were wondering why there were not learning grammar, so the reason of this had to be explained in some ocations (sic).

The teacher’s response suggests that there are challenges in both adapting the students to the new methodology and implementing tasks successfully. Thus, when working with tasks, students’ learning rhythm have repercussions on teachers’ adaptation since they need to consider the different aspects that the classes involve, such as materials, activities, and topics among others. Even though the previous excerpt exemplifies a teacher’s frustration because the methodological change, it also proves the gradual methodological shift and professional development English teachers faced during the implementation of TBI classes, which at the beginning of the project was a hindrance, it later became in a positive outcome.

Discussion and Conclusions

This paper aimed at identifying Risaralda’s English language teachers’ perceptions after the implementation of the TBI learning guides. The findings suggest that one of the participants’ perceptions is that TBI, along with the various tasks used during implementation, allowed for more engaging and enjoyable English classes for students. TBI learning guides were focused on the contexts and social realities of students, such as describing the process to make coffee, describing the most important touristic places of the town they inhabit. This enabled students to easily understand, learn, and use the language, as the tasks were directly connected to aspects they already knew because these are activities that they do with their parents in the coffee region of Colombia. For example, as students already know the process of making coffee in Spanish, they can transfer this knowledge to the English language when exposed to the task. Hence, the outcomes of this study are in line with the works of Ellis (2003) and Ismaili (2013) who mention that when students are exposed to tasks adapted to students’ needs, they see the authenticity and meaningfulness of their learning process as they identify the connection of the tasks with their context, increasing their willingness to learn.

Teachers highlighted the methodological shift they faced during the implementation of this bilingualism project. Firstly, tasks were included in the curriculum and secondly, in the class, which required teachers to adapt content and materials. Initially, most of the English classes were focused on isolated grammar and vocabulary lessons, and teachers perceived TBI to be a time-consuming approach. Nevertheless, with the inclusion of TBI learning guides and training sessions, teachers started to see the benefits of implementing tasks by teaching grammar and vocabulary within the context of a task. This agrees with the ideas presented in Cordoba (2016) , Long (2015) , and Willis and Willis (2011) . Participants of the study expanded their horizons regarding the inclusion of tasks and communicative competence without leaving aside grammar and vocabulary as tasks include them.

Along the same line, the methodological shift also has implications for professional development. Initially, teachers found that using TBI was quite demanding, as it required extra time for designing materials, lesson planning, and adapting to a new approach, particularly if teachers are used to a lighter rhythm. However, teachers eventually changed their perception of TBI and reported improvements in their planning and teaching skills, because TBI demands teachers to be more aware of the design of culture-sensitive materials, lesson planning. This corroborates what Pohan et al., (2016) and Chen and Moses (2011), who assert that TBI can enhance professional development in teachers. They further argue that the success of TBI implementation depends on teachers’ perceptions of the approach and the process they follow with their students.

Moreover, the findings show that the use of TBI learning guides gave teachers the ease to articulate their content with the different curricula proposed in public schools. Furthermore, the implementation of the TBI approach was perceived overall to be useful for the adoption and adaptation of the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) guidelines for teaching English. As presented in the English Suggested Curriculum proposed by MEN (2016), TBI is one of the approaches that facilitates the development of communicative competence.

The issue of language use is crucial to teachers’ perceptions about the challenges they face. Most teachers in the study perceived that they needed to use Spanish to avoid disciplinary problems. However, with ongoing support from the academic team of the UTP, the participants were able to change this perception and began using more English in the classroom, which helped them improve the process for developing the task. These findings are consistent with the views of Chen and Moses (2011) manifest when they say that the effectiveness of TBI implementation rests on the perceptions teachers have.

Based on the results of this study, it is recommended to concentrate on studies that explore the perceptions of a larger number of English language teachers as well as students’ perceptions regarding the implementation of TBI within the English language class. In this project, the number of teachers who could participate in the training sessions was limited due to transportation, time, housing, and personal issues, as most teachers came from different towns. Hence, it is advisable to think of virtual spaces for training teachers which enables more to participate. By the time this project was developed, the Gobernación de Risaralda requested a face-to-face learning environment for the sessions.

The result of this study highlights the importance of implementing and designing TBI classes to help students learn the English language, as well as for English teachers who seek to improve their teaching practice and professional development. Additionally, the pertinence of this study relies on the knowing the perceptions of the English language teachers in which positive and challenging ones were found. Hence, this study serves as a baseline for further research that desires to know teachers’ perceptions in the implementation, design, and execution of tasks.