Introduction

Due to the pandemic that spread worldwide at the end of the year 2019, educational communities had to turn their teaching to online platforms to reach learners’ homes. Indeed, in 2020, 1.2 billion children worldwide had to move from traditional classrooms to virtual classrooms because of COVID-19 (Xie et al., 2020; World Economic Forum, 2020). As a result, the importance of studying virtual learning environments has been brought to the forefront. Undoubtedly, the change from traditional classrooms to in-home lessons has been a complicated one for L2 teachers advocating for the importance of communication, especially considering that this change seems to be one we will continue dealing with in what is known as post-Covid education (Albidaly & Alshareef, 2019; Zhao & Watterson, 2021).

As this transition from traditional to online platforms unfolds, it is becoming evident that new challenges are surfacing for EFL teachers, particularly in the realm of fostering spoken interaction. This aspect of EFL teaching has posed difficulties for educators in even conventional settings, and in online settings these may intensify. Some of the reasons why students avoid speaking are fear of mistakes, shyness, anxiety, demotivation, and lack of confidence (Al Nakhalah, 2016; Inayah & Lisdawati, 2017). Oral production has become a sensitive issue in virtual learning environments because of behaviors such as turning off cameras and microphones (Setiawan & Fauzi, 2022). In turn, this behavior makes it difficult for the teacher to know if students are paying attention to the lesson and for the students to interact with others (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021; Setiawan & Fauzi, 2022), all of which can lead to burnout (Shlenskaya et al., 2020). In the case of second language teaching, the absence of interaction may hinder learning, as language proficiency requires practice to be developed (Chapelle, 2006; Kitade, 2000).

Since the pandemic started, researchers have explored interactions in the virtual classroom by paying attention to students’ perceptions (Echauri-Galvan et al., 2021), virtual environments in English language teaching (Herrera Mosquera, 2017), and the use of media and social networks (Ariza Covarrubias & Pons Bonals, 2021). However, little investigation has been done on how L2 teachers have faced this significant change (Lukas & Yunus, 2021). To address this gap and better understand teachers’ perceptions of how interaction in the L2 occurs in virtual settings, we formulated two research questions:

1. How have teachers incorporated digital tools into their online lessons?

2. What are the challenges teachers face when trying to promote interaction in online courses?

Literature review

The Role of Interaction in the post-Covid Classroom

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the grand majority of educational institutions worldwide. What started with what many thought to be a temporary shift in the way teaching was conducted has come to represent a far more significant change in the educational system at large (Zhao & Watterson, 2021). Several previously traditional language courses have transitioned to online or hybrid modalities (Albidaly & Alshareef, 2019); this is in line with the renewed surge of online education programs during and after the pandemic (Sadjadi, 2023). Therefore, in this post-COVID educational landscape, many teachers and students continue meeting online regularly, as well as making use of technology to offer feedback and communicate information. The pandemic’s effects have both consolidated as well as boosted online education (Xie et al., 2020).

This surge in online education presents unique challenges, including the need to help students set clear goals for autonomous learning (Carcamo & Perez, 2022; Kauffman, 2015), managing increasing stress levels (Lemay et al., 2021), and fostering diverse contexts for interaction with and among students (Markova et al., 2017). Addressing these challenges requires a focus on creating a positive online classroom environment, encompassing factors such as rapport and emotional connections between teachers and students (Alonso-Tapia & Ruiz-Díaz, 2022; Kaufmann et al., 2016). Studies indicate that fostering independent and cooperative climates correlates positively with academic performance, resilience, well-being, and learning satisfaction (Qiu, 2022; Rovai, et al., 2005). The establishment of a positive online classroom is crucial for factors contributing to online learning success, including self-regulation (Carter Jr. et al., 2020), motivation (Matuga, 2009), enjoyment (Reyes et al., 2012), and communication (Lehmann, 2004). One concept underscoring the importance of communication in a positive online classroom climate is sociability. Sociability is understood as the degree to which a learning environment facilitates the creation of a space within a group that cultivates trust, respect, and strong interpersonal relationships (Kreijns et al., 2007; Kreijns et al., 2013). Achieving a positive and sociable online learning environment should create opportunities for encouraging and maintaining social interaction, thus making it easier for learners to develop their skills (Weidlich & Bastiaens, 2019).

Social presence through effective interactions is integral to enhancing sociability in virtual learning environments (Sjølie et al., 2022). Defined as the feeling of sharing an online space with another real person through frequent and meaningful interactions in virtual classrooms (Lowenthal & Snelson, 2017; Park & Kim, 2020), social presence has been shown to serve an essential role in increasing students’ sense of satisfaction and community, learning, trust, and positive group dynamics (Molinillo et al., 2018; Park & Kim, 2020; Sjølie et al., 2022; Tseng et al., 2019; Turley & Graham, 2019). Considering these benefits, social presence should be essential for any learning community that adheres to socio-constructivist learning theories and hence values interaction. From a socio-constructivist perspective, interaction plays a crucial role in multiple educational processes, such as adapting input, offering feedback, creating learning communities, negotiating meaning, and promoting mindfulness, among others (Anderson, 2003). Recent studies have shown that isolation and lack of social interaction may lead to course attrition (Hawkins et al., 2013). For online learning to succeed at the university level, it is imperative that teachers are prepared and adequately adapt their practices to this modality. Therefore, teachers must make use of appropriate educational platforms and implement effective approaches that foster interaction in the virtual learning environment, considering that interaction can ameliorate negative feelings in students and promote autonomy (Mosquera Gende, 2021, 2022; Singh & Thurman, 2019).

Researching interaction: a matter of classification and perception

The exploration of interaction in educational contexts has been a subject of study for decades, with researchers employing quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. In order to conduct comprehensive research on interaction, it has become crucial for researchers to identify the different types of interaction that occur in the classroom and to explore teachers’ perceptions of how they manifest (Mosquera Gende, 2023; Ricardo & Vieira, 2023). Understanding how types of interaction and teachers’ perceptions can impact educational dynamics is essential for research to be useful and contribute to improvements in educational practices.

Flanders’ Interaction Analysis stands out as one of the initial systematic efforts to investigate verbal interaction within the classroom, which is fundamental for learning (Evans, 1970). Flanders’ system involves characterizing verbal classroom interaction into (1) Teacher Talk and (2) Student Talk. Teacher Talk encompasses both indirect and direct influences involve comments that help students deal with feelings, encouragement, accepting students’ ideas, and asking questions. Direct influence occurs in instances in which the teacher is giving a lecture, directions, or justifying his authority. Concerning Student Talk, Flanders identifies three instances: student talk-response, where students respond to the teacher; student talk-initiation, where students independently initiate interaction; and silence or confusion. It’s notable that Flanders’ classification primarily focuses on teacher-student interactions, which suggests a teacher-centered perspective and appears to ovelook the importance of interaction between students.

From a learner-centered perspective, Moore (1989) introduced a framework for interaction in distance education, comprising three types: learner-content, learner-instructor, and learner-learner. Moore’s framework shifts the emphasis away from interactions initiated by the teacher, placing the learner at the core of classroom dynamics. To address the challenge of finding the right balance among types of interaction, Anderson (2003) proposed the equivalency of interaction theorem. This theorem suggests that meaningful learning can occur if one of the three forms of interaction (student-teacher; student-student; student-content) is provided at a high level, without significant negative impact if the other two are lower. Moore’s (1989) framework has served as guidance for several experimental studies in the last three decades, Bernard et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis comparing interaction treatments based on Moore’s (1989) framework with other distance education approaches. The analysis of 74 achievement effect sizes revealed that educational interventions using this framework have an impact on students’ achievements, thus confirming the significance of understanding the types of interaction.

Teacher’s perception has also emerged as a valuable focus in understanding classroom interactions. Teachers’ beliefs, in fact, play a pivotal role in determining the effectiveness of virtual learning environments (Moore-Hayes, 2011) and the success of curricular changes (Bonner et al., 2020). If a teacher is not on board with an idea or misunderstands it, it is unlikely that students will benefit from it. In this regard, researchers have noted that for teachers to effectively utilize Information Communication Technologies (ICTs), they need to adopt a critical stance. This stance helps them make informed choices that can improve their teaching practice in virtual learning environments (Ricardo & Vergara, 2020; Van-Deursen & Van-Dijk, 2016).

Studies on teachers’ perception of interaction in virtual learning environments have yielded interesting findings. Mosquera Gende’s (2023) study delved into the development of oral interaction in virtual contexts, revealing that teachers linked the use of digital tools to students’ perception of progress in oral interaction in a second language, suggesting a positive impact on the development of communicative skills. Similarly, Ricardo and Vieira (2023) examined how teachers’ beliefs and perceptions of online teaching evolved during COVID-19. Their findings showed an increase in techno pedagogical self-efficacy but a decrease in the perception of the institutional support. Despite challenges such as the absence of in-person contact and assessment difficulties, teachers perceived they acquired new skills through their online teaching experiences.

Recently, employing a mixed-methods approach, Keaton and Gilbert (2020) investigated the perception of online STEM courses using an adaptation of Moore’s Framework of Interactions (1989) . Using teacher ratings, interviews, and classroom data, the researchers found that learner-instructor interactions took place in both synchronous and asynchronous online settings. While synchronous interactions primarily occurred in structured instances, such as during classroom activities, asynchronous interactions were more unstructured. The study indicated a positive correlation between in-class interaction with the teacher and student satisfaction with the course. Perceptions of interactions varied among students; some expressed happiness regarding the social interaction both within and outside the virtual classroom, while others stated that interaction did not yield academic benefits. In this sense, social interaction appears to be a factor that leads to satisfaction and retention.

In summary, it is apparent that face-to-face and digital learning environments differ, particularly regarding what makes a positive climate conducive to learning. Social presence is a factor that has been identified as key to having an atmosphere that promotes interacting with other members of the class. The importance of this construct emphasizes the relevance interaction has in virtual learning environments.

Methods

Study design

This exploratory study was conducted in a private Chilean university. Qualitative data on online classroom interactions were gathered through a survey and semi-structured in-depth interviews with EFL teachers.

We formulated two research objectives for this project:

1. Identify how teachers use digital tools to promote interaction in online context.

2. Analyze the challenges that teachers of English have to face when attempting to promote interaction in online courses.

Participants

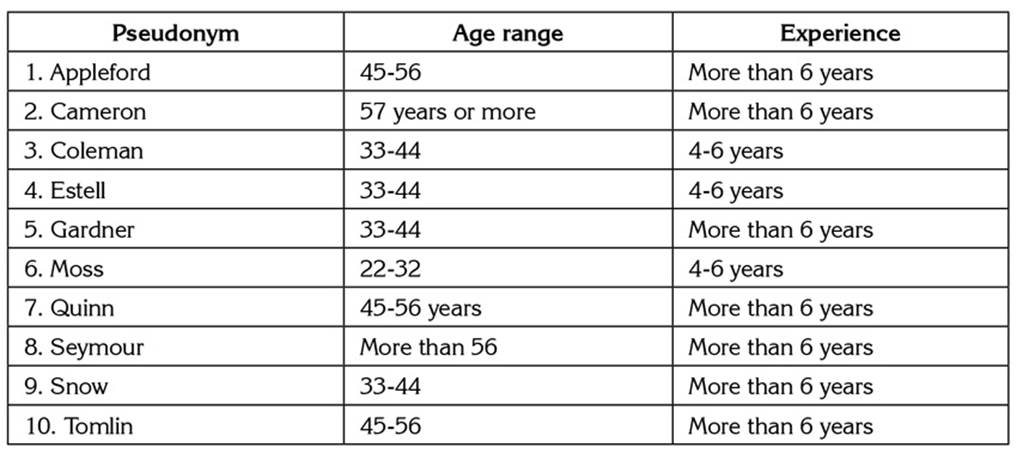

Our study involved ten EFL teachers who taught English at beginner and intermediate levels to students enrolled in various study programs, including engineering, journalism, and nursing. All ten participants had previous experience teaching face-to-face at the same university and were currently instructing either identical or similar courses in an online format. Demographic details about the participants are provided in Table 1.

As seen in Table 1, all the participants had been teaching at the university for 4 or more years. Therefore, they had experience in face-to-face teaching before the pandemic and transitioned to online teaching at the institution during the pandemic.

Procedure

To create the sample, we began by contacting coordinators of English departments in various regions of the country. We requested them to provide us with a list of the teachers in their teams who met the following criteria: (a) having taught for more than three years at the university, and (b) having experience teaching in both face-to-face and online modalities before and after the pandemic, respectively. Using the coordinators’ responses, we compiled a database of fourteen teachers who met the criteria. Ten of the fourteen teachers responded to our request. Then, we shared the consent form with them for their signatures. Upon completion, interviews via Zoom were scheduled based on mutual agreement between the participants and the researcher.

Instruments

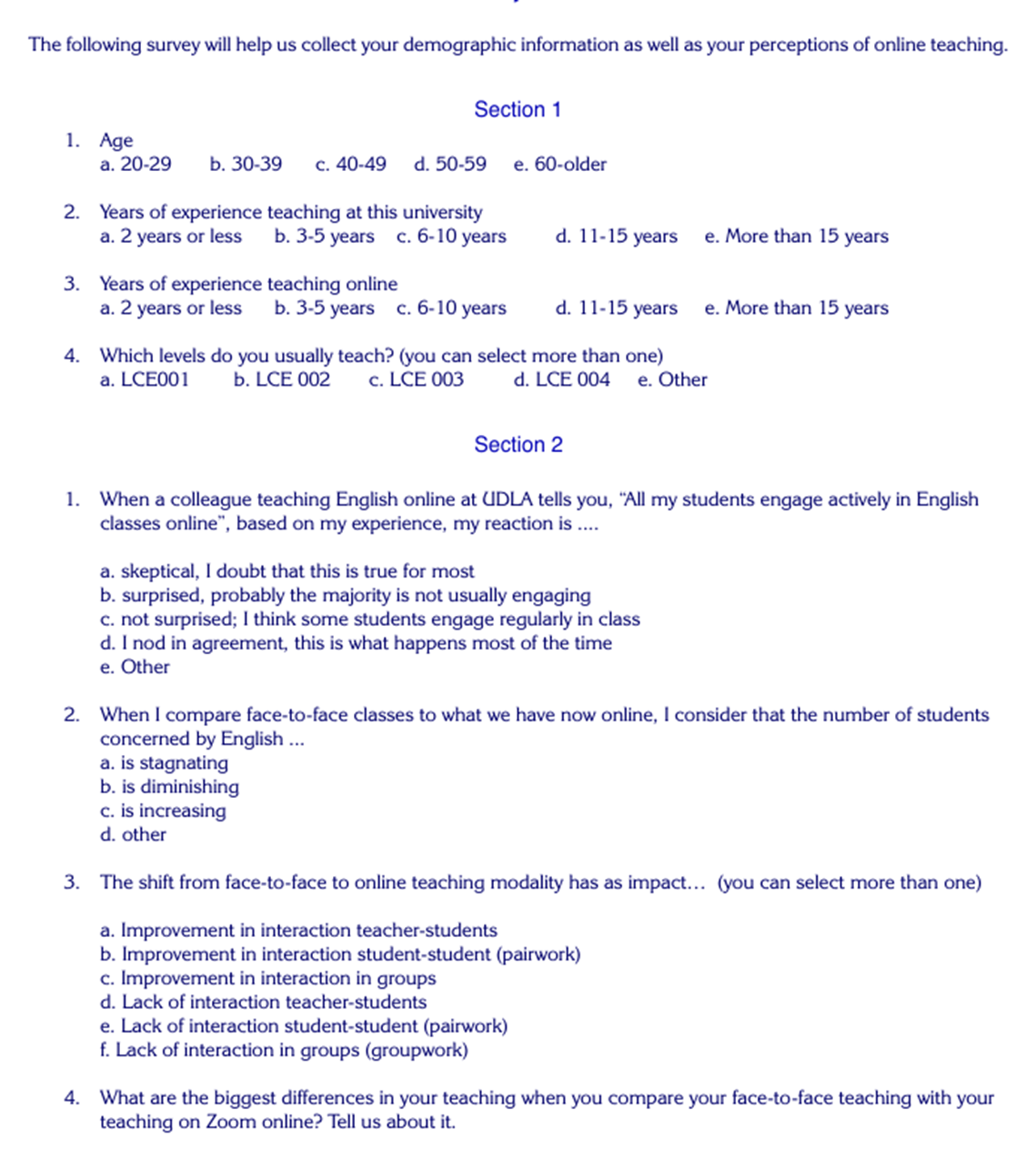

Two instruments were used to collect data from the participants. One of these instruments was a survey adapted from Toffoli and Socket (2015) . Originally focused on teacher’s perception of students’ informal online language learning habits, we selected and reformulated certain questions to apply to formal online language learning. Additionally, we asked for demographic information from the participants, as shown in Appendix 1.

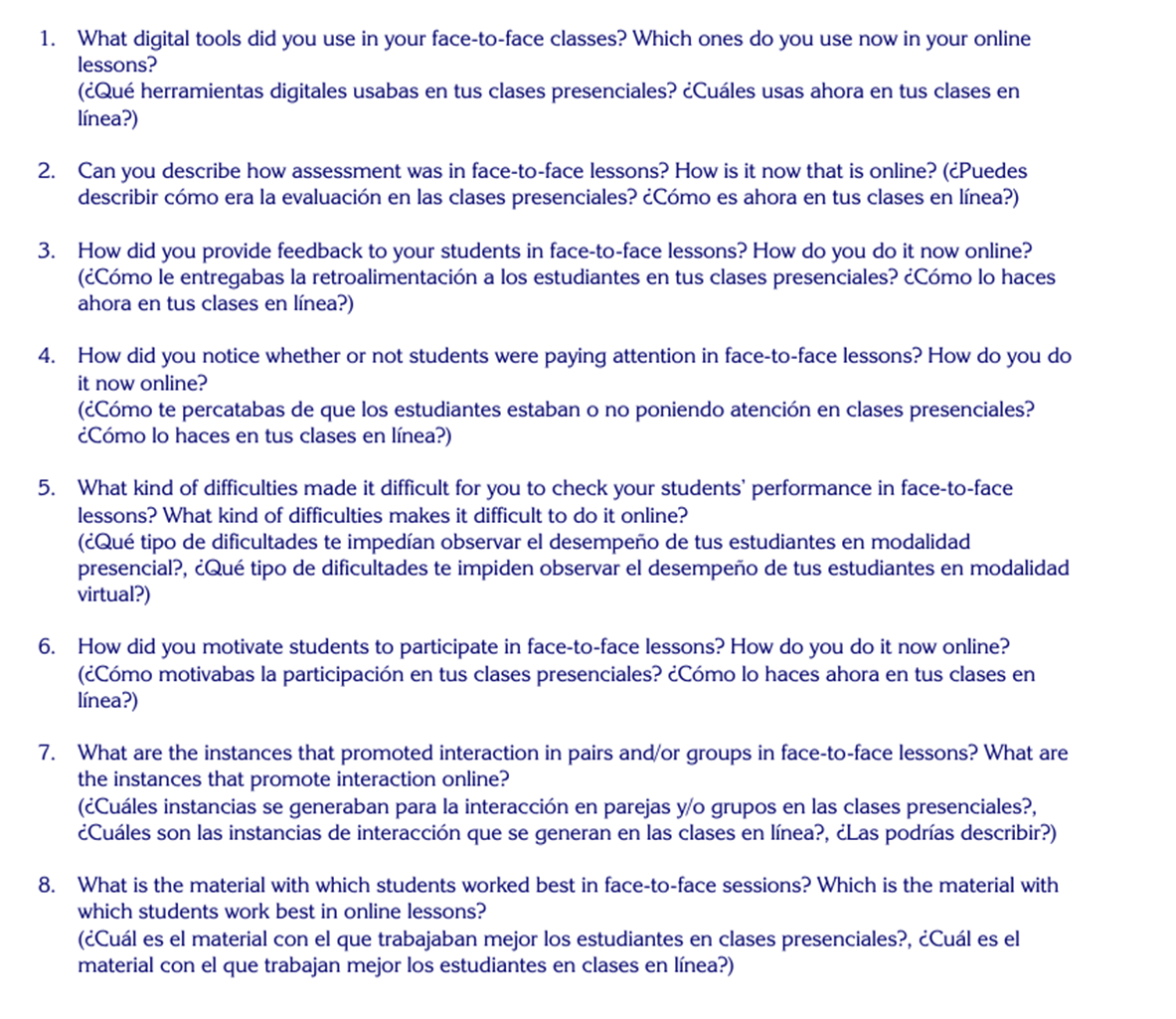

The second instrument we used was a semi-structured interview, with questions adapted from Le et al. (2022) , who designed an interview to investigate how teachers adjusted their methods to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we found that the questions originally designed for the study mainly aimed at gathering information about the teacher’s experiences teaching online. without providing much opportunity for them to elaborate on the differences between their current practices and their previous ones. To ensure that teachers explicitly addressed these differences, we edited the questions to make clear that we wanted them to compare both experiences. Appendix 2 shows the final version of the interview.

All interviews were conducted via Zoom. We opted for video conferencing because the participants were in different parts of the country, and because videoconferencing closely resembles face-to-face interviews (Irani, 2019). Each interview was recorded, transcribed, and then revised by two researchers. The total interview data amounted to 429 minutes.

Data analysis

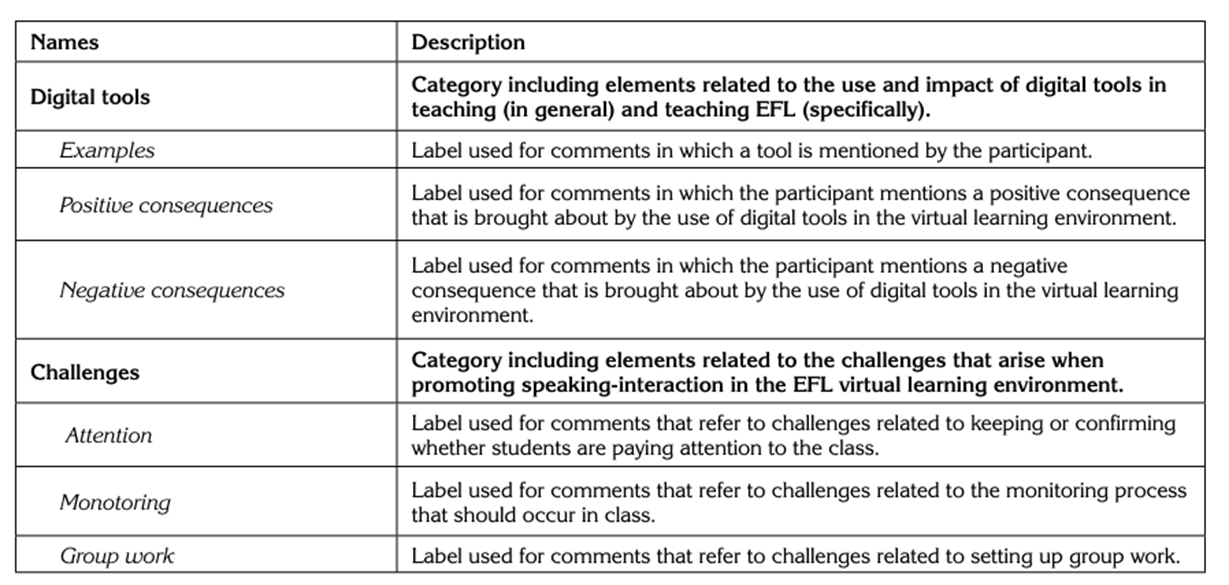

The survey data was analyzed using descriptive statistics that helped us better understand our participants. The open-ended question at the end of the survey was added to the corresponding transcripts of the semi-structured interviews. We used the software Nvivo to code and analyze the data. The resulting thematic table is shared as an appendix (Appendix 3). Specifically, the qualitative data was analyzed using Grounded Theory, following a series of coding processes that included open, theoretical, axial, and selective coding (Flick, 2018). After discovering new themes in subsequent interviews, we revisited each interview. Once the codebook was completed, intercoder reliability (ICR) was calculated by having two coders analyze separately 11% of the data (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). The level of agreement obtained was 82.5% with a kappa of .78, which aligns with the expected substantial agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Analysis and discussion

Implementing digital tools

During the interviews, teachers expressed that they primarily use digital tools they were already familiar with from face-to-face lessons, such as Kahoot, Padlet, Nearpod, and Wordwall are consistently mentioned. However, the main difference highlighted by some teachers is the systematic integration of these tools into online lessons, with both negative and positive consequences. On the negative side, teachers mention that students can become overexposed to certain tools, leading to reduced interest. On the positive side, teachers have had to familiarize themselves with more options in order to offer students greater variety. Despite initial stress, teachers recognize that this approach has helped them become more versatile and provide different options for each class.

Kahoot is always a good option although I feel that now too many of my colleagues use it, so students do not really feel like playing with Kahoot. What has worked well for me is Padlet because now I have it with lots of information. I use the same one so that students keep adding examples and even get inspiration from others. (Moss)

EFL teachers tend to connect the majority of digital tools and platforms they use in virtual learning environments with gamification. According to gamification research (Kim et al., 2018), these tools serve at least two purposes for teachers in their classrooms: they act as motivational and monitoring strategies. They serve as motivational strategies for students as they are usually well-received. EFL teachers believe that students not only can practice the language but also engage with the lesson through these activities. In addition, they serve as monitoring strategies because these platforms provide results for the participants, thereby making students visible to the teachers, even when their cameras are turned off.

I use Wordwall for games… I think it helps make the lessons more hands-on… Nearpod, Socrative, or any similar tool. These tools make students know that I am not going to be speaking all the time, and that they have to be practicing the language… I think this is motivating for them. (Gardner)

Quizizz, they love it… to know who won, who took more time… for me motivation is so important… I think that is the key as well as adapting. I am getting old, I am the one who has to adapt to the new technology, so I can use it to motivate them. (Quinn)

As Lukas and Yunus (2021) mention, during COVID-19, teachers have had the opportunity to explore materials that rely on the immediate accessibility available to students online. This contrast with traditional classrooms, where the materials often needed to be printed out. Additionally, most of the tools and materials teachers have found online are free, thus becoming affordable resources for both teachers and learners (Foti, 2020). Nonetheless, the material and tools to which teachers have access, though entertaining, seem to focus their attention on teacher-centered activities. Indeed, most of the digital material and platforms mentioned primarily enhance learner-content interaction and teacher-learner interaction, as teachers oversee the games and tasks. Although tools like Padlet offer opportunities for students to examine each other’s input, teachers often lead these activities as well; therefore, it can be stated that teacher to student(s) is the main type of interaction that is fostered through the digital tools used.

In the context of remote teaching in Chile, it has been reported that teachers have continued using teaching and assessment strategies akin to face-to face teaching, underscoring the need for specialized training (Villarroel et al., 2021). While this may not be the case in the present study, it remains apparent that teachers require training in strategies to enhance student-student interaction in online classes. As highlighted by Hernández-Sellés et al. (2023) , teachers have a crucial role in implementing collaborative learning processes in virtual environments. Consequently, it is imperative to identify and address the challenges associated with promoting interaction to facilitate effective teacher training.

Challenges for promoting interaction

While digital platforms like Kahoot and Padlet have proved useful for teachers, a recurrent challenge mentioned was the impact of students not turning on the cameras or microphones. Three main issues were identified: uncertainty about whether students were paying attention, being unable to monitor students, and not being able to implement effective groupwork. All these problems seem to originate from students’ lack of social presence during the EFL lesson (Sjølie et al., 2022).

Regarding the first issue, teachers emphasized how recognizing and interpreting facial gestures to know if students were engaged was of critical importance in the traditional classroom; this has become almost impossible in virtual sessions.

In the traditional format, everything was body language, facial expressions… it was noticeable not just the being there but being involved in it. However, in the online format on Zoom, most, if not all students, keep their cameras off. I have no way of knowing what they are doing while I explain things. (Alejandra)

There are days in which I feel alone because, of course, some days you think that maybe they are not paying attention, that you are the only one who turns on the camera, but I also have to understand that I cannot force them to. (María)

This feeling of isolation has been address in studies on online learning, which explore students’ perceptions of the online classroom. Studies have shown that peer influence can hurt students by decreasing participation and increasing feelings of isolation when most students decide not to turn on the camera or ignore the teacher (Liu, 2022; Sun, 2014). However, feelings such as those expressed by teachers during the interviews reveal that they may also have to endure isolation at times. Concerning our previous findings, it can be said that the activities teachers implement foster teacher-to-learner interactions, but interactions with learner-to-teacher that used to be expected in traditional classrooms have become more sporadic and difficult to achieve.

Similar difficulties arise with the monitoring of classwork. After teachers give instructions, they do not know with certainty if students are struggling with the activity or even doing it. Teachers indicate that, in traditional classrooms, it was much easier to find ways to monitor students’ work during class as well as to ensure the actual completion of the activities. For example, they could ask students to share their answers out loud or on the board, or check in with them while they were doing an activity to see if they were having any difficulties.

I tell my students, ‘Let’s do this exercise, you have three or four minutes’, and there we are in silence. I pause the recording. I have to trust that they are actually doing the activity… I cannot see how they are doing it. In contrast, where you are in the classroom, you can monitor, see what they are doing, and help them. (Tomlin)

Finally, setting up group work through the breakout room options on Zoom has had varied results for teachers. While a few argue that they have worked well and have achieved successful learner-learner interactions, the majority indicate that students rarely speak unless they see the teacher in the breakout room with them and that sometimes the students might be unwilling to be part of this type of activity.

In the traditional classroom we did brainstorming activities… and students would discuss in groups. I would promote this interaction depending on the level of the students… that interaction was great… but now doing that kind of activity is so difficult. (Coleman)

I have tried to put them together in groups, but some would disconnect the moment (groups were mentioned) … Sometimes I started groups with 5 in a room and ended up with 1 or 2. That was difficult. (Quinn)

Students’ reluctance to engage in group activities and use the language has been recognized as a challenge linked to negative peer influence, which leads to low participation (Liu, 2022). This is concerning as active exchanges play a vital role in fostering deeper learning in virtual learning environments (Falls et al., 2014; Koh & Hill, 2009). and their absence can serve as a demotivating factor (Liu, 2022). Teachers in our current study acknowledge that the difficulties in organizing this kind of work decrease the motivation of those students who are interested in participating. Additionally, group work is occasionally made difficult because of connectivity problems on the students’ part, which has been identified in previous studies as one of the crucial obstacles in online education (Ghavifekr et al., 2016; Lukas & Yunus, 2021). Consequently, teachers perceive that their students miss out on valuable speaking practice that would be more readily accessible in traditional classroom settings.

Considering the significant problems that the lack of interaction among learners appears to create for EFL teachers, we believe our findings challenge Anderson’s (2003) equivalency of interaction theorem. Even though teachers appear to be able to promote learner-content interaction and teacher-to-learner interaction in good measure, the lack of quality of learner-to-teacher and learner-learner interactions seems to negatively impact teachers’ motivation, students’ motivation, and the overall development of speaking skills in class. Consequently, EFL virtual learning environments must provide students with different types of rich interactions to have a virtual classroom that is conducive to developing students’ language skills and to increase positive factors related to sociability (Kreijns et al., 2013).

Conclusion

Nowadays, experts have stated that post-pandemic online education has gained enough space in the educational landscape to be considered either a significant part of the new normal, or, indeed, as the new normal itself. Given this evolving situation, it has become crucial, particularly in the context of L2 language teaching and learning, to reflect on the main challenges arising from this shift particularly regarding how teachers can be effectively supported.

In the present study, we explored how EFL teachers incorporated digital tools and platforms into their virtual classrooms and the challenges they faced when promoting interaction. Our findings indicate that teachers have attempted to integrate and systematize digital tools to face the challenges of promoting interaction. Some of the tools that have been well-received by students and effectively implemented by teachers are related to game-based learning platforms (e.g., Kahoot, Quizziz, Wordwall). Although these kinds of platforms had been gaining importance in education before the pandemic, it can be argued that COVID-19 has solidified their use as a response to issues of engagement and motivation. The use of these platforms is likely to continue increasing after the pandemic considering the effectiveness teachers report they have. In terms of teachers’ perception of interaction, two key areas have been significantly impacted: the frequency of teacher-student and student-student interaction. Teachers perceive that the lack of interaction has severe consequences for students’ speaking development, the quality of monitoring, and overall motivation.

Additionally, we identified that the lack of participation makes teachers feel isolated inside their virtual classrooms. Despite claims that online education enhances attributes such as self-regulation and autonomy, it is essential to recognize that these skills need scaffolding and development to effectively create a positive virtual learning environment. If teachers face challenges and isolation during teaching, they may become demotivated and eventually experience burnout.

Consequently, academic institutions incorporating online teaching and learning into regular programs should establish ongoing support for teachers to alleviate the potential loneliness they might feel inside a virtual classroom. These instances of support can offer opportunities for teachers to devise appropriate strategies for monitoring and motivating students, which should not only positively impact interaction, but also teachers’ well-being.

Future studies can further investigate the strategies that EFL teachers successfully implement in virtual classrooms to increase students’ participation, especially in learner-learner types of interactions. This line of research could explore innovative teaching methods that have been designed for the post-pandemic virtual classroom, considering factors to assess their effectiveness, such as teachers’ perceptions and students’ perceptions so as to obtain a holistic understanding of their use.