Introduction

Throughout the years, English has become an essential tool, not only for communication but also for professional purposes. According to Cambridge English (2016), “English language skills are important for over 95% employers in many non-native English-speaking countries” (p. 2). This scenario is of particular interest for Chilean higher education institutions, which promote the acquisition of specific job competencies. As a result, speaking skills development in social and professional contexts has become a major focus of English teaching and assessment. For instance, tourism and hospitality courses are offered at a Chilean professional institute, where, after two semesters of instruction, first-year students are expected to communicate effectively in English and reach an A2 level of English according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), and second-year students are required to progress to a B1 level after their fourth semester of English.

However, based on class observations, it was noticed that some learners struggled to master basic communicative language functions fluently. The primary deficiencies in learners’ speaking fluency were their low speech rate and frequent long pauses, which often led to communication breakdowns. In this study, a low rate of speech was considered segmented speech production at the word and phrase level; whereas frequent long pauses were regarded as extended speech breakdowns that often disrupted spontaneous oral fluency. Conversely, a high speech rate was also observed, and thus, was deemed fluent speech production at the suprasegmental level as a full sentence elaboration. The use of short pauses was considered allowable as they could be used for clarification and conversation repair without disrupting overall speaking fluency.

These learners lacked opportunities to practice the English language in an authentic context, apart from their classroom teaching, and they did not have any access to interactions with native and non-native speakers of English. The situation is different in other higher education institutions, which usually rely on the support of native English-speaking professors and foreign language teaching assistants through language exchange programs. Therefore, the present study is aimed at assessing the contribution of the Tandem language exchange application to support learners’ speaking fluency by providing an opportunity to practice with native and non-native speakers through activities that required interaction via audio recordings. In order to conduct this research, it was necessary to clearly define the research objectives describe below.

General Objective

Explore how the Tandem-language exchange application supports first-year Tourism students’ English-speaking fluency to fulfill basic communicative functions.

Theoretical framework

Speaking fluency in an EFL classroom

Fluency is an aspect of language that has been commonly associated with spoken language mastery and is considered an element that contributes to communicative competence (Tavakoli & Wright, 2020). In fact, it is a recurrent indicator in international English proficiency examinations such as Cambridge English exams. Several authors have attempted to provide a clear definition of fluency, such as Spratt et al. (2011) , who regard it as “speaking at a normal speed, without hesitation, repetition or self-correction and with smooth use of connected speech” (p. 36). Likewise, Lackman (2010) defines fluency as “a speaking sub skill together with pronunciation and accuracy and it involves learners in practicing speaking with a logical flow without previous rehearsal or planning” (p. 4).

However, the concept of speaking fluency may be broader than just natural, uninterrupted speech production. According to Segalowitz’s model (2010) , from a psycholinguistic perspective, there are three types of fluency: cognitive fluency, utterance fluency, and perceived fluency. On the one hand, cognitive fluency refers to “the speaker’s ability to efficiently mobilize and integrate the underlying cognitive processes responsible for producing utterances with the characteristics that they have” (p. 48). On the other hand, utterance fluency involves “the temporal, pausing, hesitation and repair characteristics” (p. 48) related to oral production. In contrast, perceived fluency has to do with judgements “made about speakers based on impressions drawn from their speech samples” (p. 48).

Brand and Götz (2011) acknowledge temporal variables related to fluency, such as “speech rate, length of speech runs or the number and length of filled and unfilled pauses” (p. 257). Bøhn (2015) agrees with this view noting that speaking fluency is determined by different aspects such as speech rate, number of filled and unfilled pauses, number of errors, and use of formulaic language.

Furthermore, Tavakoli and Wright (2020) , commented on Segalowitz´s (2010) framework, stating that it “is also important in reinforcing the hearer’s role in fluency as an interactional construct and not just a learner-internal psycholinguistic construct” (p. 26). Therefore, speaking fluency may stretch even further than the speaker’s own individual speech production processes and could be associated with a social interactive dimension.

Finally, this study addresses speaking fluency as a language learner phenomenon that integrates some aspects of the diverse views presented. Ideally, it is conceived as spontaneous speech that a learner mostly produces at the sentence suprasegmental level; however, such fluent oral production can make use of short pauses or hesitations in order to clarify and organize the speaker’s intended message. Nevertheless, this study does not consider speech production as fluent if it is elaborated at the segmental level, such as word or phrase framing, or if the speaker repeatedly uses extended pauses.

Tandem mobile application and speaking skill

Tandem is a language exchange app that allows users to interact with native and non-native speakers of a target language via one-on-one written messages, audio recordings, and video and audio calls. In this regard, Nushi and Khazaei (2020) suggest that the Tandem app supports oral skills because of the connection established with native speakers of the target language. The same researchers indicate that Tandem can be of assistance in foreign language teaching because teachers can motivate students to practice the target language outside the classroom in an authentic communication context. In addition, the use of the Tandem app follows important language learning principles such as reciprocity (Tardieu & Horgues, 2019), given that interaction is achieved through the partners’s goodwill to conduct the exchange process and support each other.

Even though the Tandem app can be a useful resource for improving speakers’ fluency, it cannot be denied that there are logistical issues when talking to people from distant places, such as connectivity issues depending on the area where they live. This issue was highlighted by Sophonhiranrak (2017) as the second most crucial problem in mobile learning, particularly in rural settings. Nair and Yunus (2022) also acknowledged a constraint in the practice of speaking skills using a mobile device when participants´ socioeconomic level is insufficient to own and access this kind of technological item.

Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL)

Accordingly, research has provided valuable insight into the advantages of mobile assisted language learning (MALL) for EFL learning. For instance, according to Foomani and Hedayati (2016) , the ubiquity of mobile devices provides limitless language learning opportunities in everyday life experiences and promotes learners’ autonomy. Khan and Islam (2019) claim that MALL helps to maintain the learners’ interest and motivation. In addition, Namziandost and Nasri (2019) state that EFL learners perceive social media as a valuable tool for improving their speaking skills. Their study underscores that both Iranian students and teachers concur on the potential of social networks to facilitate academic pursuits. Similarly, Dressman and Sadler (2019) agree that language exchange applications help learners gain confidence and overcome mental barriers associated with limited face-to-face interaction with native speakers. This perspective is particularly relevant given the prevailing tendency among many learners to favor instruction from native-speaking teachers over non-native speakers. The attitudes of such learners have been explored by authors such as Todd and Pojanapunya (2009) ; Alseweed (2012) ; Karakas et al. (2016) ; and Madrid and Pérez (2004) .

With regard to mobile learning, WhatsApp is a modern and easy-to-access application that can be used for language learning purposes. Indeed, Andujar-Vaca and Cruz-Martínez (2017) highlight WhatsApp as a valuable asset for English learners to make significant improvements in their oral proficiency, particularly in negotiating meaning during verbal exchanges. Similarly, Han and Keskin (2016) argue that it can significantly impact language acquisition by reducing EFL speaking anxiety. Additionally, Minalla (2018) recommends using voice messages in WhatsApp chat groups as an effective technique to enhance EFL learners’ verbal interactions outside classroom settings.

Thus, MALL may offer relevant and diverse opportunities for practicing a target language, catering to learners’ needs across various dimensions. These encompass language skills refinement, such as speaking proficiency, the cultivation of positive attitudes, including motivation and engagement, and the expansion of learners’ exposure to interactions with native speakers, while likewise fostering engagement with non-native speakers, who while perhaps not as proficient as native speakers, may still provide a significant opportunity for practice in terms of intelligibility and overall communication. Regarding speaking skills development, research on task learning, students’ oral deficiencies, and the integration of technology in the classroom are of utmost importance, as explored in the next section.

Research on speaking skills and Mobile learning

Research on the effect of mobile learning in fostering speaking skills has been an area that has been eagerly explored throughout the last few decades. For instance, Dugartsyrenova and Sardegna (2016) delved into students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of Voice Thread, an asynchronous multimodal web-based tool, for enhancing oral skills development. The findings indicated that participants acknowledged the tool’s positive impact on their oral proficiency development. They particularly appreciated the playback and recording features, recognizing them as valuable for language skills practice. Likewise, Albino (2017) evaluated the enhancement of speaking fluency among Angolan ninth graders through an 8-week intervention using task-based activities such as picture description and feedback tools such as recast and prompts. The study revealed that learners significantly improved their speech production speed, enhanced grammatical accuracy, and expanded the elaboration of their utterances. In addition, Zamani (2019) investigated the effect of cyberlearning on the speaking fluency performance of EFL learners. This study involved assessing an experimental group exposed to both traditional classroom instruction and cyberlearning sessions conducted through a virtual learning environment. Following a speaking post-test, the author concluded that learners subjected to the experimental treatment tended to decrease their hesitations and pauses due to the positive impact of cyberlearning. This contrasts with the research participants in the control group who were not exposed to the cyberlearning methodology.

Moreover, Schenker and Kraemer (2017) investigated the effects of additional out-of-class speaking practice using Adobe Voice, an iPad storytelling application, on the overall speaking proficiency, fluency, and usage of complex syntactical constructions in the German language among American learners. Their findings revealed a statistically significant difference in the overall speaking proficiency of students who received additional out-of-the classroom speaking iPad practice compared to those who did not. The use of Instagram positively favored students’ speaking performance, as they felt comfortable interacting with native speakers from other countries and engaging in discussions on topics of personal interest.

Furthermore, research on mobile learning has offered an opportunity to explore learners’ speaking deficiencies, allowing for reflection and the formulation of recommendations to improve their skills. Moreover, it has enabled the analysis of educators’ use of technological tools for instruction. Alaraj (2017) conducted a study on Jordanian learners who had recently graduated from high school and had started their first year at university. The study underscored three primary EFL speaking challenges faced by students: insufficient vocabulary (lexis), lack of listening and overall practicing, and psychological challenges. Results from a semi-structured interview conducted with a sample of 100 male students revealed that students perceived that lexis was tightly connected to EFL speaking fluency, since the lack of the former hindered the latter, leading to communication interruption and reverting to the speaker’s mother tongue. On the other hand, the research by Yang, Gamble, and Tang (2012) explored Voiceover instant messaging (VoIM) on English oral proficiency and learning motivation. Their findings recommended the implementation of prompt feedback, modeling, and encouragement to boost proficiency and motivation. Finally, Carpenter and Green (2017) conducted a study on the use of Voxer, a messaging tool which supports communication through text, voice, image, and video. Their research, involving a sample of 240 educators, unveiled that the predominant usage of this technological tool was for professional learning endeavors. Educators engaged in communication with peers from various districts and regions, prioritizing interactions with fellow educators over communication with students or family members. Participants also reported that the knowledge and insights gleaned through the use of Voxer had a tangible impact on their practices as educators.

Methodology

Participants and intervention

This is study constitutes an action research project that seeks to change and improve teaching practices within the EFL classroom. The study included a non-probabilistic and purposeful sample consisting of seven first year-female undergraduate students aged between 18 and 20 years old, all attending a Chilean higher education institution. These students volunteered to participate in this study and were part of a larger class of 30 students enrolled in the International Tourism Administration program. They were all taking their first English for Communication course. At the end of this initial course, the participants were expected to reach an A1 level of English according to CEFR. They were expected to demonstrate proficiency in basic communicative language functions, including introducing themselves, describing appearance and personality, and discussing daily routines.

The intervention consisted of four 70-minute online sessions, conducted once a week using the Microsoft Teams platform. These sessions were scheduled separately from the regular classes. Each session aimed to practice English speaking fluency by exchanging recorded voice messages with partners on the online Tandem app. If online partners were unavailable, participants engaged with offline partners. Tandem partners could vary from session to session depending on availability and were selected randomly based on their profiles. Invitations and written messages facilitated communication with them.

Participants could also send voice messages related to practiced communicative language functions such as self-introduction, describing appearance and personality, and discussing routines. The intervention design included pre-activities such as vocabulary review and video analysis, as a strategy to make sure participants focused on oral fluency when using the app. Additionally, learners were encouraged to use the Tandem app as frequently as possible after each intervention session. They were prompted to report orally during the subsequent session the amount of time they dedicated to practicing on the app.

Data collection tools and data analysis techniques

This study considered three data collection tools: a pre-intervention English speaking fluency interview, a post-intervention English speaking fluency interview, and a semi-structured interview conducted in Spanish. On the one hand, the pre- and post-intervention interviews measured the participants’ initial and final speaking fluency level. The assessment criteria in the rubric included speech rate, which ranged from segmented speech production at word and phrase level, to suprasegmental speech production at sentence level. Another relevant assessment criterion was the frequency of extended pauses, which were considered as long hesitations that broke down communication and interfered with fluent speech production. On the other hand, the semi-structure interview collected the students’ perceptions about the Tandem app contribution to the development of their speaking fluency.

The data collected was analyzed using quantitative and qualitative techniques. Simple descriptive statistical methods such as mean scores, standard deviation, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were utilized. Mean scores were used to compare the students’ speaking fluency progression in terms of use of long pauses and speech rate using an analytic rubric (see Appendix 1 for more information). The rubric was adapted considering Brown’s (2001) fluency proficiency scoring categories and it was validated by three professors. The standard deviation indicated how spread out the distribution of the participants’ scores was from the mean. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was also applied to identify any statistically significant improvement in the participants’ final scores. Lastly, the results regarding learners’ perceptions of the Tandem app, gathered from the semi-structured interview, were subjected to thematic analysis technique, which allowed the researcher to identify the main themes and subthemes mentioned in depth by the participants.

Results and Discussion

The research results obtained from the pre- and post-intervention speaking fluency interviews were analyzed according to the specific objectives outlined in the study. To ensure greater consistency and validity in evaluating participants’ oral fluency, the results of both speaking fluency interviews were assessed by two evaluators: a fellow researcher and another professor from the same higher education institution. The second evaluator had been teaching the same courses for over three years. The assessment conducted by the fellow professor was considered valid and reliable due to her status as an external assessor who did not take part in the intervention. As a result, her judgment was considered more objective, devoid of any potential bias stemming from her involvement in the project.

Speech rate and use of pauses

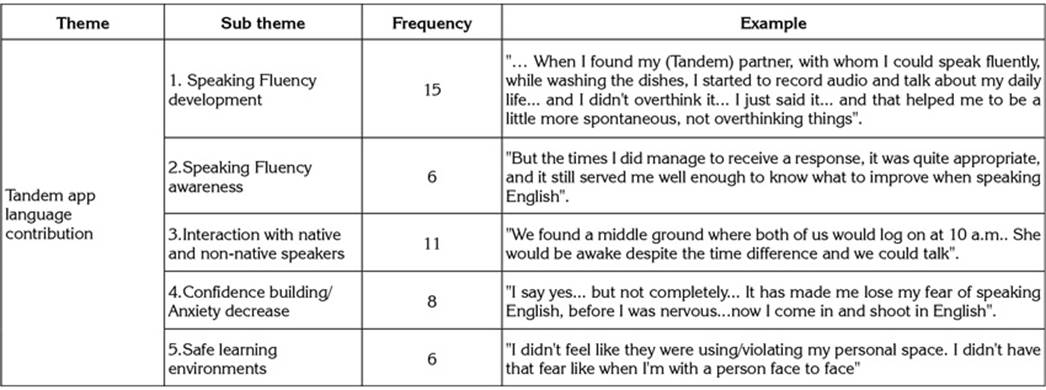

The first analysis of both group and individual mean scores from the pre- and post- speaking fluency interviews is presented in Table 1. The individual scores emerged from the analytic rubric used to assess the participants’ speech rate and the use of long pauses during the execution of three communicative functions: answering personal information questions, describing the physical appearance and personality traits of family members, and delineating daily routines. The rubic’s maximum score was 12 points.

Table 1 Mean scores and standard deviations during pre- and post-intervention speaking fluency interviews

Source: Self-reference

Taking into consideration the mean scores displayed in Table 1, it is possible to state that, as a group, there was a slight improvement of 1.57 points (13.08%) in the learners’ overall fluency level. In fact, 5 out of 7 (71%) participants scored over 9 points in the pre-speaking fluency interview, and this figure increased to 6 out of 7 (86%) participants during the post-intervention speaking fluency interview. Additionally, given the high mean scores obtained, it can be inferred that students’ initial speaking fluency, particularly concerning speech rate and use of pauses, was notably proficient. Nevertheless, minor improvements of 3 points (25%) and 1 point (8.34%) were observed in Participants 5 and 7 respectively, as suggested by the results from the post-intervention speaking fluency interview. Accordingly, participants’ high mean scores during pre- and post-intervention speaking fluency interviews were consistent with the standard deviation calculated, as shown in Table 1.

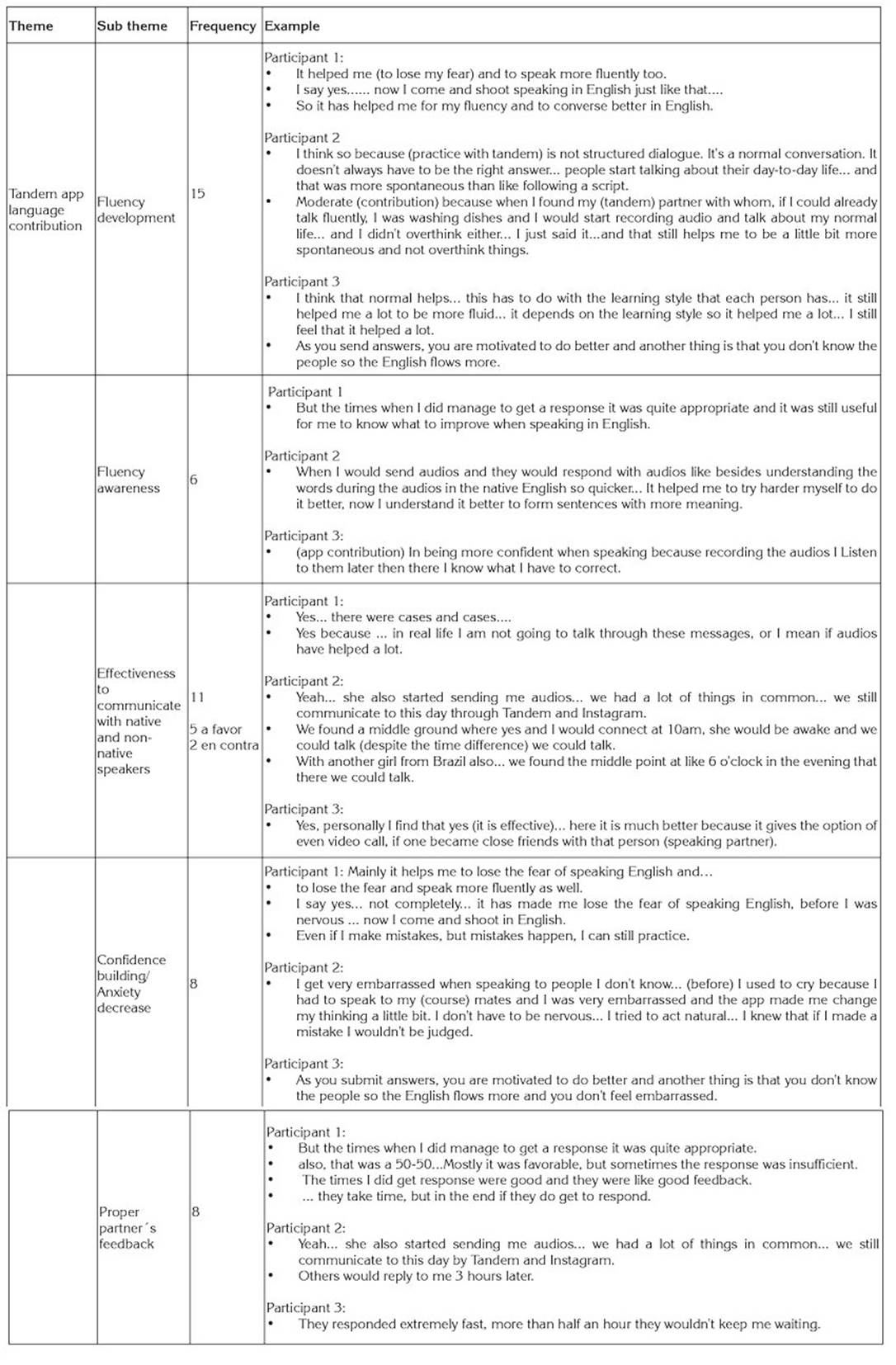

Hence students’ scores distribution presented low levels of dispersion, meaning that their results were not significantly spread out from the mean value. In addition, the post-speaking fluency interview exhibited a decrease of 0.24 points of variation in the results; this indicates that data became less dispersed due to the small improvement made by the participants in their second interview. In addition, the analysis of the results indicated a potential correlation between the time spent practicing on the Tandem app after every intervention session and the participants’ mean scores. For instance, Participant 5 and Participant 7 not only increased their overall speaking fluency mean scores but also reported some of the highest practice times, ranging from 60 to 95 minutes. These practice times were self-reported orally and registered by the teacher during each session, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Research participants approximated weekly practice time using the Tandem app outside the classroom (in minutes)

Source: Self-reference

Conversely, Participants 2, 3, and 4 ranked the lowest weekly practice time register (40 -45 minutes) and also the lowest speaking fluency mean scores during the post speaking fluency interviews. The perceptions collected through the semi-structured interview supported this finding. For instance, Participant 2 reported not having dedicated much time to practice fluency using the Tandem app, citing various reasons that deterred their engagement with the platform. Therefore, it is possible to establish a partial connection between changes in oral fluency and the timing of practice using the app. However, it’s worth noting that there are exceptions to this generalization. Participant 6, despised engaging in low timing practice (40 minutes), achieved twice the highest scores, probably due to their high scores in the pre-and post-tests. This outcome suggests that the participant may have already attained an intermediate level of English proficiency. This hypothesis is further supported by the teacher’s observations, indicating that the participant likely received effective language instruction during high school and had ample opportunities to practice the target language effectively, given their socioeconomic and cultural background.

The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was also applied to assess whether the improvements in speaking fluency exhibited by the participants was statistically significant. As per Corder and Foreman (2014) , if the critical value equals or exceeds the obtained value, the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, since the sample was comprised of 7 participants, and the test statistic value W obtained (2) is equal to the critical value (2) of the significance level chosen (0.05), the results of the learners’ performance in the post-intervention speaking fluency interview were statistically significant, considering that the improvement achieved by participants after using the Tandem app has a probability of error of 5%.

Similar advancements in speaking skills through practice involving mobile devices have been investigated by Schenker and Kraemer (2017) , who explored the effects of additional out-of-class speaking practice using Adobe Voice, a storytelling iPad application, on the general speaking proficiency, fluency, and syntactic complexity of American learners in German. Their study, which involved individual homework speaking assignments, revealed a statistically significant difference in the overall speaking proficiency of students who engaged in additional out-of-the-classroom speaking iPad practice compared to those who did not. Although speed fluency, which was measured as speech rate and calculated as the mean number of words per minute, did not present a statistically significant improvement in the intermediate speaking tasks, the overall score of the intermediate and the advanced tasks of the experimental group was slightly higher than those of the control group.

Participants’ perceptions of the Tandem app

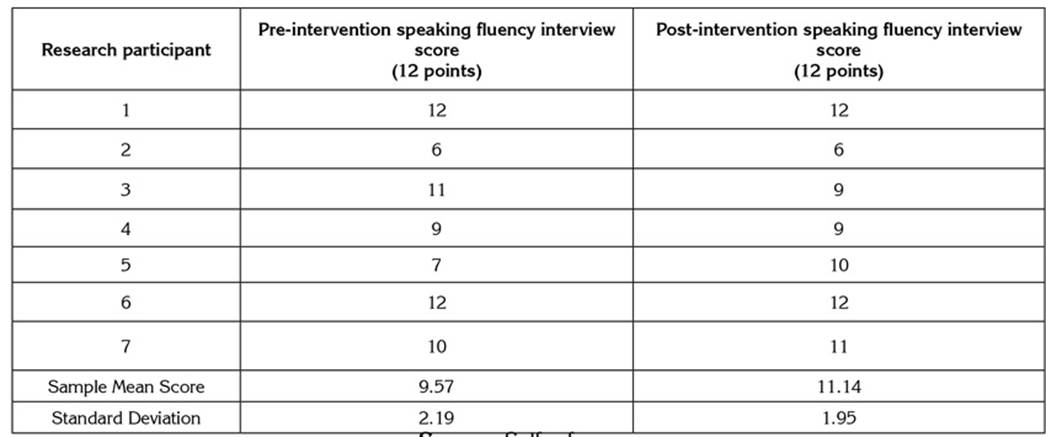

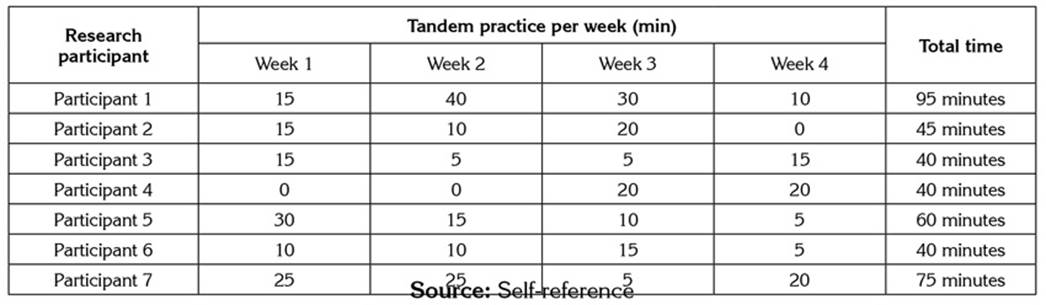

Learners’ perceptions, extracted from the semi-structured interviews, were examined using a thematic analysis. From the overarching theme concerning the Tandem app’s contribution, five major sub-themes emerged: speaking fluency development, speaking fluency awareness, interaction with native and non-native speakers, and the creation of a safe learning environment. These sub-themes are exemplified by excerpts from the participants’ comments in Table 3:

Most of the participants stated that practice on the Tandem app contributed to the development of their speaking fluency skills. 4 out of 7 (57.14%) students expressed that the app had helped them boost their confidence when speaking English, while 5 out of 7 (71.43%) learners declared that Tandem was useful in raising awareness of their own fluency and errors. Therefore, the perceptions of participants seemed to agree about the psychological support provided by this language exchange app. Similar benefits of the Tandem app are mentioned by Nushi and Khazaei (2020) , who noticed that the language exchange app assisted users not to be afraid of making mistakes.

In contrast, other sub-themes that emerged involved participants acknowledging that despite the support provided by the Tandem app, further work on their vocabulary, use of long pauses, and anxiety was needed. A few technical issues while using the app were also mentioned, such as app crashes and password control. Some suggestions for improving users’ experience using the app were also provided, for instance, enabling users to access more opportunities to use the translator feature. Nonetheless, one of the most frequently mentioned sub themes were the delayed replies (11 times mentioned) and insufficient feedback provided by some Tandem partners (repeated 9 times). Furthermore, all the participants agreed on these two negative aspects while using the Tandem app, although they differed in the length of time they had to wait for a reply, which in some cases ranged from hours to days. Regarding the amount of feedback received, this was also experienced differently since participants described finding a partner to interact consistently with as hard at the beginning. However, once the connection was made, communication tended to flow a bit more naturally.

Additionally, 1 out of 7 (14%) participants expressed having gone beyond causal interactions, being able to establish a more permanent partnership with the other Tandem users by negotiating a mutually beneficial schedule and topics to practice. This opinion was found thrice among users and it exemplifies the application of the key principles of autonomy (Holec, 1981) and reciprocity (Tardieu & Horgues, 2019) in which Tandem Language Learning is based on. In addition to that, the participants’ experience using the Tandem app may have been affected by the amount of time they used the app too, since it is very likely that the participants who devoted more time to practicing spoken English with the Tandem app might have found more partners to interact with and received better feedback than those who used it occasionally after the intervention sessions.

The ongoing process of action research did not go through without some setbacks. The main drawback encountered had to do with students’ long delays in receiving a reply to continue with the conversation, ranging from minutes to days. Occasional exchanges happened weekly as well, and even a few participants were able to establish more stable partnerships, but only after two to three weeks of practicing and sending messages and requests. Moreover, participants in general scored high levels of speaking fluency in the pre-intervention interview and, in some cases, improvement was impossible because some students (Participants 1 and 6) obtained the maximum scores (12 points) in both pre-and post-intervention speaking fluency interviews.

This high level of speaking fluency may be related to the timing practice allotted by using Tandem app and determined by their previous experience and exposure to the language. Tourism students have different socio-cultural backgrounds as well as varying levels of motivation. Typically, learners with more significant speaking fluency deficiencies would have been ideal for this research. However, to ensure a better sample size, the invitation to participate in this study was extended as a free and voluntary activity, without any prerequisites other than the learner´s eagerness to participate.

Finally, it is important to continuously question our personal approach towards teaching and assessing speaking fluency, and reflect upon what factors and fluency standards we usually take into consideration:

The narrow focus on speaker internal factors has overshadowed the significance of speaker-external and interactional factors. Moreover, the emphasis on speaker-internal factors can sometimes lead to an over-idealised or overly-native speaker-based description of fluency: ‘normal’ speed, no disruption or undue hesitation, fluid, continuous… the ideal sense of fluency may not work in authentic real-world situations. (Tavakoli & Wright, 2020, p. 147)

Therefore, an ideal native-like standard for speaking fluency might not always serve our students’ learning needs and purposes, especially when teaching a one-semester course. Consequently, by conducting research in our own classroom contexts, keeping ourselves updated about best practices and innovations, and daring to try new methods, we can further research and contribute not only to our discipline but more importantly to our students’ lives.

Conclusions

This action research project envisions oral fluency as a dynamic phenomenon, not only related to the cognitive and articulatory processes each individual experiences as in Segalowitz’s (2010) framework, but also enhanced by interaction with other target language users in an authentic context, as highlighted by Tavakoli and Wright (2020) . Similar studies on improving English speaking skills using language exchange applications such as the Tandem app are encouraged to support learners’ specific needs.

Teachers could use the Tandem app to have learners hone not only fluency but also pronunciation, vocabulary, grammar, and writing skills. For instance, through oral and written messages, the Tandem app may provide opportunities for additional practice on syntactical patterns such as Wh- and Yes/No questions. Through voice messages and video calls, students could practice basic communicative language functions such as the ones this research has already covered, and more advanced ones, for example, giving and justifying opinions and talking about hypothetical situations. Moreover, analyzing audio messages and chat history could be useful for learners to reflect upon their pronunciation, accuracy, register, and use of discourse markers.

Furthermore, compelling methodological considerations regarding the integration of the Tandem app in the everyday classroom remain to be researched, such as the establishment of more stable partnerships with Tandem users. If a more permanent connection between learners and Tandem users were to be achieved, it might be possible to support the lack of exposure to native and non-native speakers of English that students usually encounter. Additionally, Tandem could be used for an extended period, such as a semester, to research how the app supports students’ overall oral proficiency. In order to deal with limitations such as delayed responses and international timing settings, this study recommends that teachers encourage students to use the Tandem app among classmates and members of other English courses and learning communities. Alternatively, teachers may organize Tandem networks among native speaker contacts they might have and/or among non-native language practitioners such as students from different programs. Finally, this action research study highly recommends the use of technological tools such as the Tandem app, as its use contributes to developing learners’ positive attitude towards learning a foreign language, while providing them with the opportunity to improve their speaking skills by interacting in the target language with other users in real-life settings.