Introduction

The development of language learning strategies (LLS) is a recurring research topic in the field of Applied Linguistics. In Colombia, for instance, a glance at national academic journals from the past four years reveals a wealth of research on strategies, confirming a consistent and growing concern among teachers in fostering students’ abilities to plan, monitor, and evaluate their progress in foreign language acquisition. Taking a more active role in monitoring their own progress is an ability expected of autonomous learners, rendering language learning strategies a crucial necessity at early stages of the learning process. Under the model that Oxford (2011) has called Strategic Self-Regulation (2R), “learners actively and constructively use strategies to manage their own learning” (Oxford, 2011, p. 7).

With this in mind and convinced that instructing students in strategies and autonomy helps them learn and use the language more effectively, two researchers at the School of Language Sciences, Universidad del Valle, carried out two independent action-research cycles with pre-service language teachers. The first study, reported in Hernández (2016) , involved an action-research cycle in an English class for beginners. The participants were first-semester students from the Foreign Language Teaching Program at Universidad del Valle. The objective was to assess the impact of teaching learning strategies on student’s development of self-regulation in language learning. One of the most important results from this study suggests that a specific sequence is necessary in implementing learning strategies to foster autonomy. Furthermore, the study suggests that for instruction on strategies to have a positive impact, it should take into consideration a small number of strategies, ideally no more than three strategies at a time. A similar conclusion was drawn by Guapacha and Benavidez (2017) , who suggest that working with a small set of strategies over extended periods enables better monitoring of progress and prevents overwhelming students.

Similarly, Ramírez (2017) implemented an action-research project, which sought to design and evaluate two syllabi for the development of student autonomy. This project involved a different group of first-semester students from the same bachelor program. The results suggest that a short-term intervention is needed to challenge a prevalent cultural tendency toward a lack of autonomy among Colombian students. Additionally, the results underscore the importance of substantial changes in syllabus design for these initiatives to succeed (Ramírez, 2017).

The outcomes of both projects have been integrated into an instructional proposal for language learning strategies aiming at promoting learner autonomy. The proposal has been conceived as an adaptable intervention suitable for any institution, curriculum, or syllabus. Likewise, the fundamental principles for the design of this proposal are applicable across any level of instruction and to groups varying levels of foreign language proficiency, whether low, intermediate, or advanced. The proposal is structured in three stages, each with distinct goals. The first stage is aimed explicitly at raising awareness among the participants about the strategies they are already using for learning the foreign language; the proposal understands these strategies to be of a spontaneous nature. This means that they are developed by the learner with no instruction, and they are closely related to learning styles or common pedagogical classroom interactions. The second stage of the proposal is envisioned as the cornerstone of the instructional process, as it comprises a set of strategies designed to foster the development of learning strategies, objective setting, progress monitoring, and the evaluation of outcomes. This second group of strategies requires intense instruction and direct promotion within the language course for a conscious acquisition, as the learner is expected to develop essential skills fundamental to the development of an autonomous human being. The third stage aims to consolidate the acquisition of the strategies in a way that allows the learner to apply them in settings and aspects of their life. The goal of this proposal is to facilitate the transfer of strategic knowledge developed within the context of the foreign language to other areas of the participants’ academic and personal lives. The authors of this paper share our proposal in the hope that the academic community of English teachers in Colombia might scrutinize, adapt, and comment upon it, with reference to their own respective contexts and experiences.

Conceptual Framework

LLS as a path for the development of learner autonomy

In the early 70s, in the heyday of the communicative approach, the new focus on language as communication brought a burgeoning demand to explore novel concepts and methodologies for the instruction of foreign languages in the classroom. As a result of this new movement in language teaching, the concept of strategy appears in conjunction with the concept of autonomy. Some authors like Rubin (1987) state the need to adopt strategies as an objective in foreign language teaching. In Rubin’s (1987) view, explicit instruction regarding strategies should benefit learners in terms of their efficiency and degree of independence in their learning process, both of which are paramount in the development of future autonomous professionals (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Chamot, 1999, Oxford, 1990, Nunan et al., 2000; Cohen, 1987).

This interest in providing explicit instruction on learning strategies originates from a desire to raise awareness among students about the importance of taking an active role in the learning process and eventually assuming full responsibility for their learning. Some studies demonstrate that successful learners make efficient use of learning strategies (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990; Green & Oxford, 1995; Anderson, 2005; Hernández, 2008). When a learner understands their learning process as an active and constructive process, they constantly strive to develop skills that enable them to establish learning goals, monitor their actions, regulate and control cognition, motivate themself, etc. All these actions contribute to shaping an autonomous learner, and eventually an autonomous human being. In a similar vein, Pintrich and de Groot (1990) argue that actively participating in the learning process means looking for opportunities to understand, practice, and learn. In this sense, Oxford (1990; 2011) states that developing cognitive, metacognitive, affective, and social strategies contributes to developing communicative skills and stimulates active participation in communicative situations both in and outside the classroom. In other words, learner autonomy represents a destination that is reached through the development and implementation of effective learning strategies.

LLS and curriculum design

Thus far in this article, the importance of LLS has been extensively demonstrated. Its relevance is also recognized within the educational sphere when educational reforms integrate conceptual and behavioral components into their proposed curricula. Educational professionals have traditionally focused on conceptual content, but there is now an evident need to integrate this conceptual and behavioral content. This is crucial for empowering students to effectively navigate their academic journey. Students are entrusted with a great responsibility, but institutions and academic programs are also responsible for providing students with the appropriate setting to build their knowledge and to develop robust tools for self-directed learning. To address this requirement, curriculum design needs to signal the use of strategies within the context of general education, enhance content delivery, and promote independent thinking and autonomy in students.

According to Deng (2010) , curriculum planning must progress through three levels of development: the institutional level, the programmatic level, and the enacted level. At each level, the curriculum must be designed to cater to students’ needs in terms of both conceptual and behavioral content. When seeking to integrate these two types of content, both the institutional and the programmatic levels of the curriculum need to be addressed, as they collectively determine the national perspective in education. The institutional level formulates national goals in education, whereas the programmatic level provides standards and criteria aimed at establishing a relationship between the broader national educational framework and the design of institutional documents, such as school activity plans, curriculum planning for specific subject areas, among others. Deng’s (2010) curriculum model directs the enacted level to the classroom: it gathers all documents and materials circulating in the classroom which are the product of interaction between the teacher and the students.

Within this perspective, instruction on learning strategies can be formulated and developed at the enacted level when planning classroom workshops, activities, tasks, or projects. Regardless of the class’s methodological orientation, each piece of work might designate a space for developing learning strategies that promote the integration of behavioral content into the learning process. However, it would be desirable for this work to be conceived at a previous level that includes specific, formal institutional documents, such as those previously mentioned: the institution’s general plan for specific academic periods, institutional academic projects, or differentiated curriculum for specific subject areas. These documents should undoubtedly be fully informed by and aligned with institutional perspectives, values, principles, and goals. This ensures that the proposal for instruction becomes institutionalized, preventing it from remaining solely a “one-man” endeavor.

It is clear, however, that merely issuing institutional documents is not enough: if the design of a curriculum based on the development of learning strategies is to work, it is necessary to introduce the idea, ensure comprehension among teachers and students, create an environment conducive to promoting their active participation, demonstrate various methods of implementation, and encourage continuous practice until the use of the strategy becomes habit. When this happens, students are empowered to experiment with new approaches and explore diverse applications in different contexts to successfully construct their own strategic style for learning and living.

Context and participants that inspired the proposal

The instruction proposal was conceived within the Foreign Languages (English-French) program at a public University, specifically targeting newly admitted students at the introductory English level. The research conducted by Hernández (2016) and Ramírez (2017) involved 50 students in total (25 students in each research project) aged between 16 and 18 years old. Around 90% of these participants had graduated from public schools, and their English level was A1 at the time of admission. The English course adopted an integrated skills approach and was taught in two-hour sessions, three times per week.

It is worth noting that this proposal emerged from collaborative reflection between the researchers who, while sharing similar research interests individually and independently, had not previously coordinated joint interventions. Additionally, a preceding study from the same institution, as reported by Guapacha and Benavidez (2017) , informed the design of the proposal. This underscores the importance of establishing bridges, dialogues, and connections between research projects, colleagues, and studies that are carried out within the same, or at least in similar, academic contexts. It is precisely through this dialogue that complementary findings were identified in the results of the separate investigations, consequently giving rise to this proposal. This dialogue allowed for, on the one hand, the identification of conclusions in relation to the instruction of the strategies themselves, and on the other hand, the recognition of the need to conceptualize the instruction of strategies within a curricular framework.

Strategies Instruction Proposal

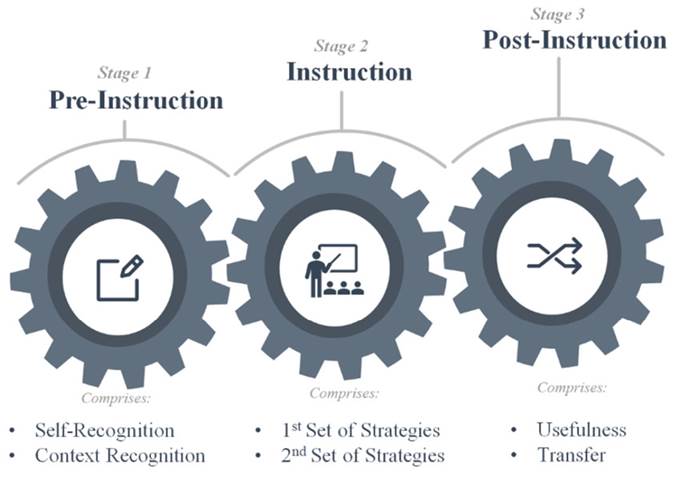

A key feature of this proposal is that it can be adapted to any context, any language level, or any curriculum. The proposal comprises three stages, following the pre-while-post sequence with which most teachers are familiar. An overview of the proposal is provided in Figure 1.

The first stage, or pre-instruction, is designed to help students get to know themselves as learners and understand what the institution expects from them. The second stage, the core of instruction, focuses on the development of six strategies, divided in two sets. Lastly, the third stage, or post-instruction, centers on reflecting upon the acquired strategies and exploring other contexts for their potential application. We now move on to scrutinizing the inner structure of each stage.

Stage 1: Pre-Instruction

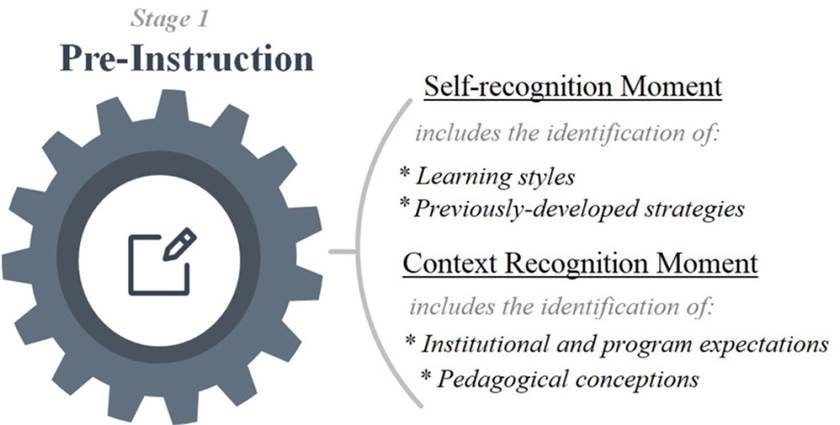

The initial stage comprises two phases: self-recognition and context recognition, as shown in Figure 2. First, the phase of self-recognition implies raising awareness among students regarding their identity as learners, which involves identifying a). their learning styles, and b). the strategies developed and adopted naturally throughout their lives, including those from non-academic settings. Figure 2 shows the inner structure of this stage:

Andreou et al. (2008) define learning styles as “a student’s preferred mode for perceiving, organizing, and retaining information” (p. 665). Together with learning strategies, learning styles “appear to be among the most important variables influencing performance in second language” (Moenika & Zahed-Babelan, 2010, p. 1170) because they offer a glimpse into learners’ individuality: their likes, needs, and personal objectives. Equipped with this understanding, learners can choose and refine learning strategies that are “appropriate to the material, to the task, and to their own goals, needs, and stage of learning according to individual differences” (p. 1169). Indeed, the study conducted by Moenika and Zahed-Babelan (2010) reveals that learners perform differently in the four main language skills depending on their personal learning styles, indicating that identifying their individual traits may help them enhance their innate abilities while pinpointing weaker areas from the outset.

Similarly, learners need to be made aware of the learning strategies they have acquired naturally outside the classroom. Moenikia and Zahed-Babelan (2010) , building on Oxford (1990) , remind us that learning strategies are the often-conscious steps or behaviors used by learners, implying a set of strategies and skills that may not be fully understood by the learner. For instance, Ramírez (2017) reports that the students who participated in his research demonstrated behaviors of strategic and autonomous learners in many aspects of their personal, non-academic lives. Some students were self-taught instrument players, while others had developed skills in arts and crafts by watching videos or following tutorials. Some had even achieved financial independence by applying strategies to their budgets. All these life skills required the development of learning strategies and a high degree of autonomy triggered by the students’ unique, intrinsic needs. Nonetheless, the same students who had successfully overcome different obstacles in their lives seemed to struggle when it came time to apply their learning strategies and autonomy to an academic context. It was only when they were made aware that their background knowledge relied heavily on a set of organically acquired strategies that they were able to bring those strategies into the classroom.

Secondly, the phase of context recognition involves informing students of what the institution and program expect from them and the pedagogical principles that underpin institutional practices. These expectations are often summarized in the graduate profile and general objectives. It is vital that learners identify these expectations and contrast them with their own expectations for there to be harmony between the institution’s vision for its students and learners’ personal objectives. For instance, Hernández (2016) reports that, at the beginning, the students in her study expressed astonishment at how much responsibility and independent work was expected of them, as their own expectations of their role might have differed. In the same vein, Ramírez (2017) reports that, in a course which promoted learner autonomy, students were initially reluctant to participate in designing course objectives or learning materials because such activities had never been part of their role as students in their previous experiences.

This discussion on roles leads us to the second aspect involved in recognizing context, which entails understanding the pedagogical concepts that underpin institutional practices. Both the teacher and the students need to reflect on the pedagogical interactions they establish, as well as on the institutional definitions of teaching and learning, the conception of language, and the particular methodological approaches that take place within the classroom. Students are often excluded from methodological decisions made by teachers, depriving them of valuable information for a successful performance and the establishment of clear and strong pedagogical commitments (Cotterall, 1995; Ramírez, 2015). Being aware of the pedagogical principles of a course, along with acknowledging the roles of students and teachers within their pedagogical relationship, promotes commitment to the institution, the program, and the learner’s personal life project. It also facilitates establishing and adjusting goals, both as a professional and as a human being.

Recognition in this stage can be consolidated through dialogue sessions between the institution and the learner (Ramírez, 2015), enabling the establishment of academic agreements. Building on Cotterall (1995) ; 2000), learner/teacher dialogue “implies constant communication between the teacher and the learners, which allows for constant assessment. Therefore, constant communication results in confidence, as constant assessment involves a continuous monitoring of the learning process by both the teacher and the learners” (Ramírez, 2015, p. 116). Regular communication can be guaranteed through the implementation of questionnaires that target the self-recognition of previous (and perhaps unconscious) strategies, as well as polls focused on personal learning styles. Additionally, the use of guided reflection logs on strengths and challenges of the learning process is encouraged (Hernández, 2016), as well as the use of journals. Journals have proven to be highly beneficial and rewarding in fostering the development of learner autonomy (Brown, 1994; Fulwiler, 1991; Nunan et al., 1999; Viáfara, 2005).

Stage 2: Instruction

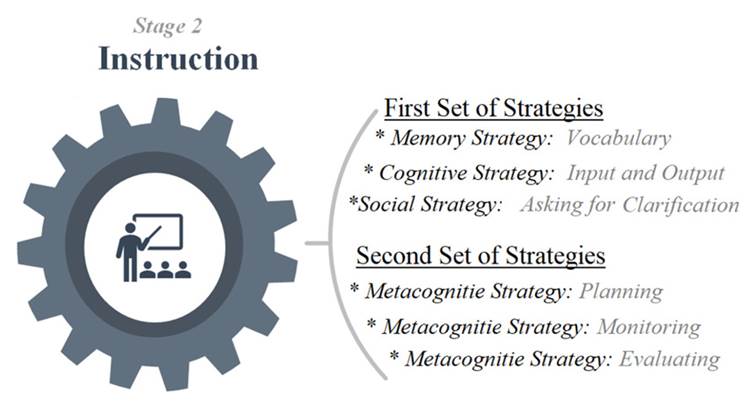

The second stage of the proposal corresponds to the core instruction, or “the While” phase. This stage unfolded in two phases: The first comprised the enhancement of three strategies, chosen from the memory, cognitive, and social categories established by Oxford (1990) ; 2011). The second phase comprised a new set of three metacognitive strategies aimed at fostering learners’ continuous reflection on their learning process: planning, monitoring and evaluating. It is worth noting that the number of strategies we recommend for each moment is not arbitrary. Drawing from our experience in previous research projects, we encountered a challenge in monitoring more than three strategies simultaneously, as each strategy requires in-depth development. Moreover, having more than three strategies tends to overwhelm students and, ultimately, the lack of constant accompaniment in the development of every strategy individually might demotivate them, increasing the risk of not using any of the strategies. Figure 3 shows the two set of strategies proposed for the second stage:

The first set of strategies has been thought out as preparation for the second set, as the strategies in the latter require greater effort to be acquired. We will now proceed to explain each strategy in detail. Firstly, the strategy “Vocabulary”, categorized under “Memory Strategies”, has been chosen as a starting point due to its practicality for assessing development. Learning vocabulary allows learners to set simple and quantifiable goals. Upon achieving these goals, students experience a sense of continuous progress, which in turn motivates them to continue learning. Similarly, vocabulary serves as one of the fundamental building blocks of communication, providing learners with essential elements for oral and written interaction in the foreign language from the outset. Finally, learning vocabulary is closely linked to the exercise of memory. This connection entails the exploration and recognition of learners’ memory types (whether visual, auditory, or kinesthetic), as well as their learning styles and preferences; in other words, the strategy of learning vocabulary strengthens the process of self-recognition proposed in stage 1.

The second strategy categorized under “Cognitive strategies” is called “Input and Output”. According to Oxford (1990) ; 2011), the purpose of this strategy is to make the most of the input received to produce some basic output. One way to leverage class input is asking students to provide a brief account, either orally or in written form, of what they have accomplished in class. This approach places special emphasis on the objective behind each activity; by doing so, students are encouraged to comprehend the activity, summarize it, and analyze the learning objective that underlies the instruction. At this level, the priority is to identify main ideas of texts in comprehension and to make summaries. Through this strategy, emphasis is placed on the recognition of the objectives behind each activity. This is particularly important because, as noted by Hernández (2016) , despite their commitment and willingness to participate in class and comply with what they are asked, students are not always aware of –or do not analyze on their own– the educational purpose of the activities they perform in class.

Finally, the first set is completed with the strategy “Asking for clarification or confirmation”, categorized under “Social Strategies”. This approach encourages learners to pose questions that arise within the pedagogical dynamics of the teaching-learning process. For Hernández (2016) , asking for clarification or confirmation should be taken as evidence that the learners have understood the greater part of an issue. Doubts, observations, confusion, or sheer curiosity are capitalized upon though this strategy to articulate questions that foster interaction with the teacher and other peers. Asking for clarification and confirmation provides learners with an opportunity to solidify the information they receive from classroom input and produce genuine output for the scrutiny of an audience.

Once learners have received training and experience in the first set of strategies, they are expected to be able to analyze teacher’s pedagogical decisions. Moreover, it is likely that they begin to make some decisions independently in favor of their learning process. Against this background, the second phase of this stage focuses on a new set of three strategies, –all of them chosen from the “Metacognitive strategies” category–which establish the grounds for the learners to constantly assess their learning process. The first strategy is “Planning”, which goes hand in hand with designing and setting objectives. The reason why learners need to be instructed in how to plan and set learning objectives is because these are not easy tasks, nor have they been in the domain of the learners. In Ramírez’s study (2017) , for instance, participants would usually feel reluctant to set their own objectives as they cast this responsibility on the teachers’ role. In Hernández’s (2016) , on the contrary, participants did want to set their own objectives, but they would often design and write goals that had nothing to do with their contexts or the needs they had previously expressed. Thus, “Planning” is intended to help learners to design learning goals in consonance with the pedagogical context that surrounds them: the institution, the class, the specific didactic unit they are in, the particular class activity they are expected to comply with, etc. Similarly, we recommend that learners be instructed in the basics of composing in written form the goals that they express orally.

The second strategy, “Monitoring”, focuses on tracking the process, the progression of the activities, and the assessment of students’ own learning process. Monitoring helps learners to seize their strengths and weaknesses, allowing for the establishment of new objectives in a cyclical process. It also enables the student to calibrate their initial objectives: if progress is either too difficult or too easy to measure, the learner realizes the objective has been designed incorrectly. In monitoring, students also develop the capacity to provide feedback to their own learning, and in the ongoing assessment action, they become critics and objective evaluators of their learning process. This strategy requires deep and constant reflection on the part of learners, and when it is fully developed it might take students to assume autonomous behaviors and self-regulation, which foster a better self-esteem and fuels the desire for further learning.

Finally, the third strategy of this set is “Evaluating”. In traditional approaches, various forms of evaluation typically fall within the purview of the teacher. However, in student-centered classrooms seeking to foster autonomous learning, evaluation processes are encouraged as part of the learners’ role. Evaluating implies making a synthesis of the monitoring process. It is a strategy that allows for the closure of process, so that new goals and objectives can be designed in the long term. Ramírez’s study (2017) revealed that students did not initially feel comfortable or confident in evaluating. They tended to either assign themselves very high grades, anticipating that the teacher might deduct points, or assign themselves very low grades, hoping for praise and extra points from the teacher. This type of behavior revealed that students needed to be trained in taking a critical and objective stance vis-à-vis their learning process. Learners have been deprived of evaluation processes for so long that they feel evaluation has to do with pleasing the teacher or with doing well on metric scales, rather than with assessing what they have learned and what they lack. Therefore, we recommend that training for this strategy includes various types of evaluations: self-evaluation, peer evaluation, teacher evaluation, and syllabus evaluation. Furthermore, we encourage teachers and learners to engage in sharing their evaluation with their peers. When evaluation is openly discussed among peers, learners establish comparison standards, can compare their learning process with that of others, and may recognize the diversity of learning styles, preferences, pacing, and backgrounds within learning. In other words, evaluation should be a process that allows students to acknowledge who they are as learners, and to see themselves as part of a diverse collective.

Stage 3: Post-Instruction

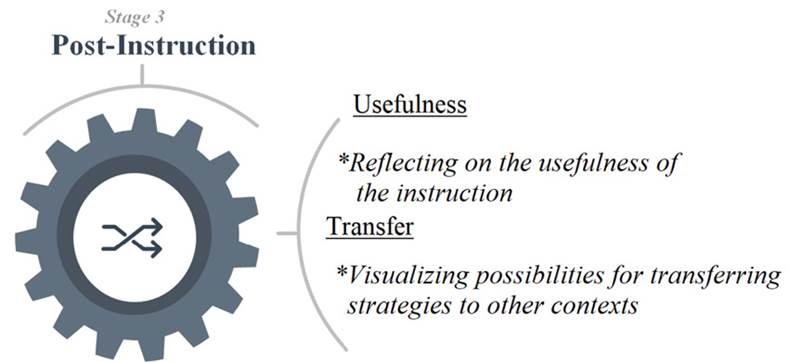

The third phase, called “post-instruction,” aims at reflecting and transferring the acquired knowledge to other settings of the students’ lives, including both academic and non-academic settings. Figure 4 shows the inner structure of this stage:

In the same vein as the previous stages, this one is also divided into two phases: a period of reflection on the effectiveness of the instruction, and a second phase of envisioning possibilities for transferring it to other contexts. Reflecting on the entire instruction allows students and teachers to assess the endeavor and adjust for future implementations. At the same time, students are reminded of their journey guided through and can identify aspects of their learning process where the instruction on strategies made an impact or not. This is what Navaneedhan (2011) calls “reflective teaching and learning”, that is the process of “looking at what you do in the classroom, thinking about why you do it, and thinking about if it works-a process of self-observation and self-evaluation” (p. 331). The experience of Ramírez (2017) suggests that a good tool for this type of reflection is found in the constant dialogue sessions between the teacher and the learners, as well as in the use of “KWL Charts” (see an example in the Appendix). Students need to be guided through other categories of strategies that they might find useful, and that this instruction may have not included.

The second phase involves transferring the strategies developed to other areas in learners’ lives. Although there can be an immediate transfer (for instance, students applying some strategies in other courses while receiving the instruction in an English course), we want our students to develop a long-term transfer, meaning that strategies acquired in the academic preparation might become tools for other academic and non-academic settings. As an anecdote, the participants in Ramírez’s (2017) research developed strategies that they used in other courses immediately. However, two years after the research, the teacher asked some of his former students about how the strategies continued to impact their lives; the answer was overwhelming: the strategies had been part of that particular course, but once the learners moved on to other courses with other teachers, the instruction became a part of the past. This anecdote suggests that, after an instruction in strategies, it is desirable for students to have a space for reflection on how new learning tools can become permanent allies, which are available when they, autonomously, decide to use them even in contexts where there is no teacher or authority present.

To this end, Hernández (2016) proposed a series of spaces that she called plenaries. These consisted of group sessions led by the teacher, where students share their perceptions about learning and implementing strategies. They discuss how they are currently applying strategies, as well as brainstorming possibilities for further transfer. Plenaries provide a highly productive context for idea-sharing, as students are exposed to their peers’ insights on learning strategically and transferring their knowledge to other settings, which they might have not considered before. Moreover, these sessions constitute a moment for self-evaluation, in which learners identify the progress they have or have not made vis-à-vis the report of their peers’ progress.

These strategies have been chosen deliberately. The reason behind this sequence has to do with the intention of taking learners from lowest to highest degree of difficulty in acquiring learning strategies. Proposals such as those of Dolmans et al. (2016) Hattie and Donoghue (2016) , distinguish at least three groups of strategies: surface strategies (easier to acquire), deep learning strategies (understanding and analysis of process), and transfer strategies. Likewise, recent studies show the importance of promoting the gradual exercise of strategies in students based on their learning styles, so that they evolve from surface to deep (metacognitive) learning and transfer strategies, thus guaranteeing lifelong learning (Saqr et al., 2023; Yamaguchi, 2023; Barani et al., 2023).

Although this marks the conclusion of formal instruction, it is necessary for us as teachers to convey to students that this is merely the commencement of their journey toward autonomous learning. This instructional phase must culminate in a collaborative reflection between the teacher and their students. Through this reflection, students become cognizant that the success of their learning now hinges on the level of autonomy they decide to exert in their own process. In this sense, the structure of this instructional proposal matches perfectly the five degrees of autonomy proposed by Nunan (1997) .

According to Nunan (1997) , the first stage of autonomy development is awareness, which occurs during the pre-instruction phase, where students familiarize themselves with their learning styles, previous experiences, and strategies. The second stage, involvement, also occurs in the pre-instruction, where students are expected to design their own learning objectives. The third and fourth stages in Nunan’s proposal are called intervention and creation respectively, which students participate in adjusting the learning objectives they had initially designed. In our proposal, this corresponds to the instruction phase, where students learn how to plan, monitor and self-evaluate their learning process. Finally, Nunan (1997) explains that the last degree of autonomy development is the stage of transcendence, which matches our post-instruction, where students are expected to be strategic and autonomous learners beyond the classroom setting.

Final Considerations

In this sense, the implementation of this instructional model can be extended over the course of a school year, semester, or academic period; it all depends on the educational context in which it is applied, considering factors such as the number of students, their age, academic maturity, exposure to foreign language instruction, institutional policies, curricular objectives, and so on. We consider that this characteristic of adaptability is indispensable in education, since we relate with diverse and unique human beings, which means that what works for some may not work for others; hence the importance of developing proposals that are in constant construction and adjustment.

For such proposals to be effective, it is imperative to formally integrate them into curriculum and syllabi design. Otherwise, there is a risk that the proposal remains confined to the individual initiative of a single teacher, potentially limiting its impact and failing to achieve the desired outcomes. About this institutional backing, Hammond and Collins (1991) assert that

an innovation needs to be incorporated into the structure and functioning of its host institution within a short time if it is to survive: it needs to be institutionalized. If it is not institutionalized but merely tolerated as a minor aberration, it is unlikely to be taken seriously by learners or faculty, and may well fail completely. (Hammond & Collins, 1991, p. 208)

As mentioned at the beginning, the design of this model was motivated by its adaptability to various contexts and populations. Although the population that inspired the proposal was made up of two groups of undergraduates, we consider that the sequence, pre-instruction, strategies instruction, post-instruction, can be applied to any age group and educational level. However, activities and materials for each phase would need to be adapted according to the age and academic level of the population. For example, during the first stage of self-recognition and context recognition, an elementary school teacher might use games and posters to remind students of institutional expectations, while a teacher of an adult group might utilize a multiple-choice test to explore learning styles or discuss the course syllabus to emphasize student expectations. Despite variation in activities, the principle of self recognition and context recognition remains consistent across different age groups and educational levels.

Similarly, during the strategy instruction stage, adaptations can be made to accommodate different educational settings. For instance, when considering in the first set of strategies, specifically in the memory category, a primary school teacher might employ various techniques to help students remember family vocabulary: drawings to cater to visual learners, a song for auditory learners, and charades for kinesthetic learners. Likewise, a university professor could use the same resources and materials for his students to memorize the conjugation of irregular verbs in French. In this case, neither the activity nor the target strategy have changed, but rather the degree of difficulty, depending on the cognitive development of each population.

One aspect to take into account when implementing this proposal is the amount of time it requires. As teachers, we must open room in our syllabi for the development of this type of endeavor, which can generate in us a certain reluctance to surrender control and part of the traditional teaching pacing. However, any initiative aimed at developing learning strategies leads students to gradually develop new autonomous behaviors and acquire learning that may even exceed the planning of traditional pacing. This implies challenging traditional conceptions of the roles of students and teachers. This is not an easy task, especially for teachers (Ramírez, 2017). For instance, Cárdenas et al. (2001) illustrate how English teachers at six Colombian universities expressed a strong interest in their students’ autonomy development. Yet, they encountered significant challenges in negotiating syllabus design, class participation, and class procedures. As a result, their role as teachers often took on an authoritarian and paternalist nature.

Finally, it is important to mention that many strategy categories have not been considered in this proposal, though this should not be interpreted as a lack of importance. The strategies and sequence outlined here intend to boost learner autonomy to the extent that students can eventually acquire other strategies on their own This implies that while the proposal focuses on specific sets of strategies, students should still be informed about the full range of strategies and categories available. If implemented correctly, the proposal enables students to autonomously plan, monitor, and evaluate the acquisition of other strategies without requiring constant teacher guidance.