Introduction

Breast cancer represents 10% of new cancer events in the world every year1; It is the main cause of mortality in women between 35 and 64 years old.2 In Colombia, it is the second malignant tumor in women and causes 1,700 deaths yearly3.Mastectomy, quadrantectomy and lymphadenectomy are the most frequent procedures in breast oncology surgery4,5.

Reported incidences of surgical site infection (SSI) vary between 10.2% and 30.0% and are higher than those of other clean surgeries (2.07%-3.9%).4,6-13The incidence of SSI in breast surgeries with prosthesis range between 2.5 and 30.0%.14

Our study estimates the incidence, associated factors and time freedom of infection at 30-days after breast oncology surgery with or without immediate reconstruction.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study of 308 patients with breast oncology surgeries at Clínica Las Américas, Medellín Colombia, between August and December 2011. The procedures were radical (complete mastectomy with or without axillary lymphadenectomy, and with or without immediate reconstruction), or conservative (quadrantectomy, tumorectomy).

Inclusion Criteria: Women 18 years old or older who underwent lective breast oncology surgery, with or without immediate reconstruction.

Exclusion Criteria: Active breast infection at or near the intended surgical area at time of surgery.

The post-operative follow up was conducted by a trained team of physicians and nurses and begun with a medical examination in the first week after surgery; patients had additional medical and nursing controls if they needed; at 30 days after the procedure, patients had a telephone follow up with a pre-structured format and a new medical control was schedule when it was necessary.

Data collecting instruments had three moments: pre-operative evaluation, intra-operative follow up and post-operative follow up. The researchers did not modify the routine patient medical care. Socio-demographic variables were evaluated (age, socioeconomic status, educational level, type of health insurance); medical and surgical history, comorbidities and previous treatments; current procedure data including antibiotic prophylaxis (if was indicated), surgery executed, type of surgical wound, duration of surgery in minutes and use of drainage devices. The post-operative follow up included medical evaluation, wound healing, antibiotic use, drainage device used (in days), hospital readmission, surgical re-interventions related to the index procedure, presence of seroma-hematoma and SSI.

The adequate prophylactic antibiotic treatment was defined as the administration of cefazoline, clindamycin or vancomycin, 15-60 min before surgical incision, according to our institutional protocol.

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of University of Antioquia and the Research Ethics Committee of Clínica Las Américas.

The primary outcome was SSI cases, defined according to the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control, version 2008.8 And secondary outcomes were seromas and hematomas diagnosed by attending physicians.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were described by proportions and its independency relationships were established with Chi-square test. For quantitative variables, the mean, measures of central tendency and mean differences were determined. The Relative Risk (RR) was calculated for the incidence of SSI, according to type of surgery. Confusion and interaction were also evaluated. Cox proportional-hazards regression model was used to estimate the Hazard Ratios (HR) of SSI by the stepwise method, when the Log Rank Test p value was <0.25. The time to event was the number of days between surgical intervention until first infection symptoms in a range of 30 days postoperative. Deaths unrelated to SSI and losses of follow up were considered as censures. The statistical analysis was performed using the PASW Statistics (SPSS Inc., Version 18.0. Chicago: SPSS Inc).

Results

The SSI rate was 16.2% (50/308); the infection was classified as superficial in 36 cases (11.7%), deep in 14 (4.5%) and none organ/space SSI (Fig. 1). The median time to SSI diagnosis after surgical intervention was 16 days (IQR: 10-22). Nine of 40 patients with immediate breast reconstruction were diagnosed with SSI (22.5%).

There were no significant differences in socio-demographic variables among the patients (Table 1). Previous history of breast surgery was present in 63 women (20.5%), diabetes mellitus in 34 (11%) and obesity/overweight in 161 (52.3%). The delimitation of surgical field was performed in 211 patients (69%) employing sentinel lymph node in 130 (61.6%), sentinel node plus self-retaining anchor wire in 55 (26.1%) and only self-retaining anchor wire in 26 (12.3%). Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to 307 patients (99.7%), it was adequate in 77.9%; no differences were found between types of surgery. The overall median time of surgery length was 90 min, interquartile ranges (IQR) 65-120; for conservative surgery it was 70 min (IQR: 55- 97.5), and for radical surgery, 115 min (IQR: 85-135).

Postoperative hospitalization was one day in 199 (64.6%). The median time until the first medical evaluation after hospital discharge was 9 days, (IQR): 8-16.

The postoperative follow up was performed by a physician in 217 patients (70.1%), by a physician and a nurse in 58 (18.8%) and by a nurse alone in 12 (3.9%). All patients were alive at the end of follow up.

Twelve patients had readmission (3.89%) due to SSI, with a median readmission time after surgery of 18 days.

Drains in situ were used during a median of 16 days (IQR: 12- 22). Seromas-hematomas were detected in 79 cases (25.6%) and of these, 33 (41.8%) were drained. Inadequate manipulation of drain in situ was observed in 12.2% of cases.

The axillary node clearance was a risk factor in the bivariate analysis, RR 2.8 (95% CI: 1.67-4.74; p value <0.01), but it was not statistically significant in the multivariable model. The delimitation of surgical field was a protective factor in the bivariate analysis, RR: 0.49 (95% CI: 0.3-0.82; p = 0.006) (Table 2).

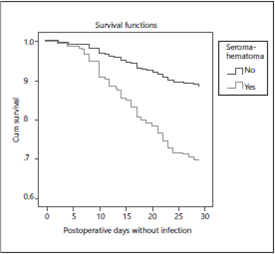

In patients with prolonged postoperative drain device SSI was higher than those without drainage, HR: 5.6 (95% CI 2.2-14.3, p < 0.000). The infection proportion with sili-cone suction drain (Jackson Pratt(r) ) was 6.7% versus 27.0% with polyvinyl suction drain (Hemovac(r) ) and it was higher in patients with seroma-hematoma, HR: 2.7 (95% CI: 1.55-4.96, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

SSI is one of the most important complications of breast oncology surgery that frequently occurs after patient discharge. In this study the most important risk factors were prolonged postoperative drain device and seroma-hematoma.4,9,10

The persistence of a drain in situ was a risk factor for SSI. The extended persistence of drains, washing tubes to remove fibrin clots, connection and disconnection of proximal tubes without standardized aseptic practices increase the risk of infection.4,11-14Some authors recommend removal of the drain when drainage volume becomes less than 30-50 ml/ day during 48 h; others recommend their removal at fixed time intervals (5-7 days); in our study, the median time of drainage was 16 days4,7,14-18. Future studies should be directed to remove the drain in less time.

In the postoperative period, the most frequent complications in breast oncology surgery were seroma-hematoma formation, with higher risk of SSI for seroma and for hematoma, increased the mortality and length of hospital stay.12,19 In our study, postoperative seroma-hematoma incidence was 25.6% while in others it ranged from 18% to 59%.6,14,15,20-22A case-control study showed that seroma-hematoma puncture and drainage were risk factors for SSI20.

The risk of developing SSI was significantly higher for mastectomies vs conservative surgeries in our study; other reports showed SSI incidences of 38.3% and 18% respectively.11 Studies with one year follow up in breast surgeries with immediatere construction reported similar incidences of SSI (2.5-30%)6-8.

Wire localization delimitation of the surgical field and radiocoloid injection before surgery showed a protective association; the limitation of intervention area decreases the risks of postoperative adverse events. The axillary node lymphadenectomy showed statistical differences in the development of infection. These findings are similar to other published reports14-23.

Follow-up was completed in a high proportion of patients, this is strength and it was possible compared preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factor.

The most important risk factors mentioned in the literature were evaluated. Next studies should appraise shaving of patients at home and their relationship with SSI. The strengthening of postoperative epidemiological surveillance systems, the use of silicone drains and sterile techniques to manipulation of tube11,13,14are practical tools to evaluate the reduction in seroma-hematoma formation and drain time in other studies.

In conclusion, our study shows that presence of postoperative seroma-hematoma and long time drain device were independent risk factors for SSI on oncology breast surgery. These results should encourage further studies on tools to help remove the drains in less time and avoid the formation of seromas and hematomas.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of people and animals. The authors state that for this investigation have not been performed experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that they have followed the protocols of the workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that this article does not appear patient data.