Skin-to-skin care/contact (SSC) is when the infant is placed prone on the mother's chest or abdomen with no cloth separating them. SSC should be encouraged as soon as possible after either vaginal or cesarean birth, SSC should be uninterrupted for at least 60 minutes, unless medically contraindicated 1,2. SSC is part of a neurobehavioral approach that recognizes and facilitates the infant's innate breastfeeding behaviors that enable them to find and self-attach to the breast often referred to as the "breast crawl", sometimes termed "biologic nursing." Breastfeeding should be encouraged and initiated as soon as possible after birth during this period of SSC. Immediate SSC and early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF) are two closely linked interventions that need to take place in tandem for optimal benefit. While feeding cues of healthy term infants are evident in the first 15-20 minutes after birth, they may diminish a few hours after birth. Weighing, measuring, and routine care for the infant should be delayed until the first breastfeeding is completed 1,2.

Benefits of early initiation of breastfeeding for mothers and newborns

The benefits of EIBF for mothers and babies are well documented 3-8. Many unique effects of EIBF are attributed both to the contact between infant and mother and to components found in breast milk;

Self-attachment by the infant through breast crawl reduces the risk for breast problems such as cracked or sore nipples.

SSC supports newborn's temperature regulation (reduced risk of hypothermia), vital signs stabilization, blood sugar levels maintenance, and metabolic adaptation. EIBF decreases the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage compared to routine hospital practices.

EIBF and SSC strengthen the mother-infant bond.

EIBF makes it possible to take colostrum, which contains immunological bioactive factors and growth factors. EIBF help to populate the newborn's micro-biome. Colostrum reduces neonatal morbidity, the risk of many infections including diarrhea 3,5, and the risk of developing neonatal sepsis 6. Similarly, initiating and establishing breastfeeding in the first hours and days of life has positive effects including optimum growth and development well beyond the time available in maternity and neonatal services.

EIBF will trigger the production of breast milk and accelerate lactogenesis and is associated with the increased rate of exclusive breastfeeding practices and ensure longer breastfeeding duration 7.

A study analyzing exclusive breastfeeding in 27 sub-Saharan African countries with a Multilevel Approach using MLwin found 12% higher odds of EBF in EIBF as compared with late initiation 7.

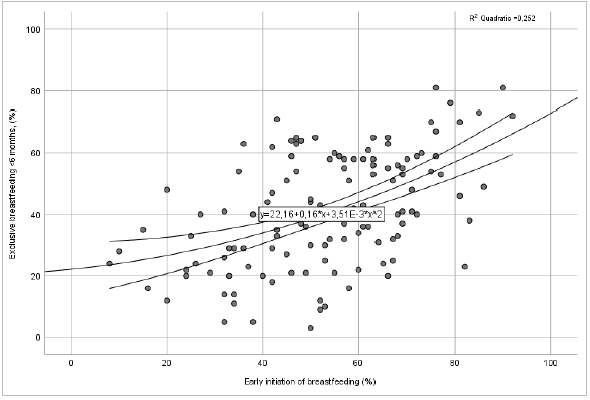

DHS, MICS, and other national household survey data 9 belonging to 133 countries from WHO-UNICEF data, 2015-2019 showed a positive association between EIBF and EBF as seen in Figure 1.

Delayed initiation of breastfeeding (DIBF) deprives children from the protective characteristics of EIBF and increases the risk of developing neonatal sepsis and death in the early neonatal period 3,6,10. The interaction between mortality and DIBF is documented with an increasing trend with the postponing duration 11. DIBF can also increase the risk of prelacteal feeding 12.

Global status for early initiation of breastfeeding

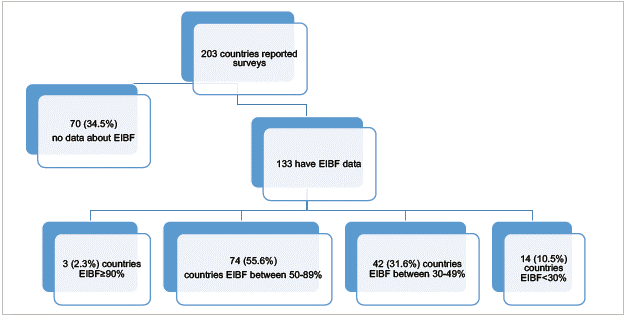

The WHO classified the percentages of breastfeeding within 1 h after delivery as poor, fair, good, and very good (o%-29%, 30%-49%, 50%-89%, and 90%-100%, respectively) 13. According to the report of 203 countries from WHO and UNICEF 9, 70 (34.5%) countries did not collect any EIBF data. Three (2.3%) countries in 133 had the rates more than ≥90% and 14 (10.5%) countries had EIBF<30%, 74 (55.6) countries had EIBF between 50-89% (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Distribution of breastfeeding rates by countries according to WHO classification 70 (34.5%) no data about EIBF

Nearly half of newborns are breastfed within the first hour after delivery 14. The rates of countries having EIBF ≥70% in WHO-UNICEF data were given in Table 1. Turkey 71% and Colombia 69% were in the good zone. The prevalence of EIBF changes from region to region (15-17); 35% in the Middle East and North Africa and 65% in Eastern and Southern Africa 16.

Table 1 Countries having EIBF >70%

| Countries | EIBF % | Countries | EIBF % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eritrea | 93 | Malawi | 76 |

| Burundi | 92 | Nauru | 76 |

| Sri Lanka | 90 | Rwanda | 76 |

| Uzbekistan | 86 | Sierra Leone | 75 |

| Vanuatu | 85 | Zambia | 75 |

| Kazakhstan | 83 | Cabo Verde | 73 |

| Oman | 82 | Ecuador | 72 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 81 | Ethiopia | 72 |

| Samoa | 81 | Namibia | 71 |

| Solomon Islands | 79 | Turkey (2018) | 71 |

| Bhutan | 77 | Mongolia | 70 |

The World Breastfeeding Trends Initiative (WBTi) evaluated EIBF in European countries and found no systematically collected data on EIBF in 6 of 18 countries 18. The average rate for 12 European countries was 57.2%. Rates ranged widely, with the highest in Portugal (84%) and the lowest in North Macedonia (21%).

Determinants of EIBF

Previous studies have suggested that family characteristics (such as place of residence, income status, family support for breastfeeding, and cultural factors), maternal characteristics (such as age, educational level, marital status, employment status, knowledge about the importance of breastfeeding, and experiences from previous pregnancies), characteristics of the last child (such as whether the pregnancy was wanted, birth order, preceding birth intervals, antenatal visits, place of birth, modes of birth, gestational age, need for neonatal resuscitation at birth, sex, and birth weight), and health facility factors (such as timing of skin-to-skin contact and lactational counseling) are all associated with early initiation of breastfeeding (EIBF) 15,17,19-22.

Older mothers are more likely to be experienced and knowledgeable due to previous births, and EIBF rates are higher among them compared to younger mothers. Inexperienced and insecure young and nulliparous mothers tend to report more negative postpartum practices and difficulties with initiation of breastfeeding 23.

Research indicates that women who begin to consider breastfeeding early in their pregnancy have a higher initiation rate (approximately 9.6 times) and longer breastfeeding duration, underscoring the importance of early prenatal education, including nutritional strategies 24. Insufficient or inaccurate knowledge about breastfeeding and breastmilk is considered one of the predictors of poor outcomes in EIBF. Therefore, pregnant women who receive breastfeeding counseling are more likely to initiate breastfeeding early 25. Additionally, women who receive support and encouragement from family members are more likely to initiate breastfeeding early.

Negative cultural beliefs about early breastfeeding and colostrum include:

The belief that colostrum is unhealthy or even harmful to newborns 26. One study reported that 25-35% of mothers discarded colostrum with the belief that it would be difficult for the newborn to digest and would cause cramps 25.

The belief that breast milk does not come immediately after birth 27 and that milk will not be sufficient in the first three days 28.

The perception that the mother and baby need to be cleaned and bathed after birth 29.

The perception that the mother and baby are tired and need rest after birth 28.

The perception that babies sleep and do not show any signs of hunger after birth 28.

In a qualitative study conducted in Turkey on the breastfeeding practices of Syrian refugees, it was found that mothers with a low pain threshold and a desire to sleep preferred to feed their babies with sugar water and baby formula instead of breastfeeding 28. In Northwest Ethiopia, approximately three-quarters of mothers reported early breastfeeding initiation and colostrum feeding to their newborns. Among the mothers who did not initiate breastfeeding within the first hour after delivery, 46.4% reported fatigue, 14% reported cesarean section, and 11% reported insufficient milk as reasons 30.

Several studies have reported that the mode of delivery is one of the main determinants of EIBF status in newborns and that cesarean delivery delays the initiation of breastfeeding 21,31-33. A Baby-Friendly Hospital in Turkey showed that the rates of initiation of breastfeeding in babies born by cesarean section were significantly lower, up to the 4th hour, compared with babies born vaginally 31,32. Generally, delay in SSC, fatigue, and then delay in the start of breastfeeding are seen due to the sedative effects of anesthesia and additional procedures and problems that may occur to the mother and the baby due to cesarean intervention 21,31,33.

Delayed breastfeeding was also associated with maternal illness during pregnancy, maternal anemia, and gestational age 32. Many studies found that preterm newborns are more likely to experience issues with initiating breastfeeding 23,25. This result can be explained by problems such as limited oral-motor skills of the preterm infant, increased risk of hypoglycemia, delayed lactogenesis in preterm births, and maternal adaptation to a small infant.

Birth at health facilities has non-consistent results, which might be due to the presence of baby-friendly hospitals 32,34. Compared to public health sector childbirths, EIBF rates were lower for private hospital-born children in the Middle East and North Africa and Latin America, and the Caribbean, and for both private and home deliveries in South Asia 12.

The association between wealth disparities and EIBF might vary according to region and country. One study reported that the difference between the highest and the lowest wealth indices in nutrition indicators, including the EIBF ratio, was significant only in Latin America and the Caribbean 12. This could be explained by the fact that highly educated women in Peru have both higher cesarean section rates and greater purchasing power 12,23. Another study showed that higher household wealth groups had greater coverage of SSC and EIBF in (concentration index=0.152, p<0.001 and concentration index=0.103, p=0.002; respectively) than lower wealth groups in Nigeria. The greater the degree of inequality including the mother's education, the more the curves deviate from the line of equality 35. Significant wealth-, residence-, and educational-related disparities were found in EIBF rates in both 2000 and 2011 in Ethiopia but disappeared in 2016. This was associated with mass communication, public spot broadcasts about EIBF and breastfeeding to families having infants in the previous two years and they were found to be 80% effective 36.

Health care practices can have both positive and negative effects on breastfeeding 23,28,37. Good practices support breastfeeding by enabling mothers to successfully initiate and continue breastfeeding for longer periods. It is known that infants followed by nurses, midwives, doctors, or traditional birth asistants who have the knowledge and skills to supervise breastfeeding practice are more likely to achieve EIBF 37. Inadequate breastfeeding counseling during prenatal visits and the influence of the formula industry, or the lack of national strategies to promote immediate breastfeeding, create barriers to the positive impact of health care.

The WHO Secretariat conducted a qualitative review to examine mothers' views on early skin-to-skin contact and initiation of breastfeeding, and from 286 published studies on the subject, 13 articles, performed in Australia, Colombia, Egypt, Italy, Palestine, Russia, Sweden, Great Britain and Northern Ireland (United Kingdom), the United States (USA), were determined to be suitable for inclusion in the review 11. In general, it was found that mothers who had both normal and cesarean deliveries valued SSC and were happy to apply it. One mother reported that when she had skin-to-skin contact with her baby, she "forgets the pain" and that it "helped her heal"(n).

The 15 studies for early SSC and EIBF in Australia, Canada, China, France, India, New Zealand, and the United States were conducted in health workers and stakeholders; 7 studies were for favourable views towards early SSC, 9 for safety concerns during SSC after cesarean delivery or epidural anaesthesia) and 2 for concerns about breastfeeding and SSC when the infant was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Most maternity staff had favorable views towards SSC after delivery. Some health personnel had concerns about early SSC and breastfeeding, especially after deliveries with anesthesia 11.

Although most maternity staff are aware of the positive effects of early SSC, some have reported that it is not always reasonable to implement this step and start breastfeeding within half an hour of delivery and that it is impractical and unsafe to initiate breastfeeding in the operating room. It has been reported that the routines of the operating room will hinder this practice and it is desired to remove the mother and baby from the delivery room as soon as possible after delivery. One study noted that it is impractical, if not impossible, for nurses to initiate breastfeeding in the operating room due to the mother's physical position, the risk of contamination of the incision site, and possible disapproval by doctors.

Healthcare providers have reported safety concerns for early SSC and breastfeeding for infants admitted to the NICU. Common concerns were physiological instability and dislodging of the intravenous and umbilical catheters. Although neonatal ICU staff are aware of the benefits of SSC, they report that it is better to ignore this intervention because the risk to infant safety is too great 11.

Interventions to improve EIBF

Risk-group-specific planning is required. Some strategies have been proposed that may improve breastfeeding status at birth 2,11,16,34,38-43.

Accurate and effective information about the benefits of EIBF to pregnant women should be provided in the health institution, in the community, and different settings, including the media.

Guiding mothers with appropriate delivery methods can reduce cesarean deliveries except for medical indications.

Cesarean section should not prevent the mother and baby from early contact. Mothers who are given spinal or epidural anesthesia are awake enough to respond to their babies immediately. Training of health personnel on how to support breastfeeding after cesarean section improves SSC and EIBF rates. A supportive healthcare worker is important to help the mother start breastfeeding after a cesarean section. When this is not possible, a trained family member can help the SSC keep the baby warm and confortable and start breastfeeding.

Elective interventions for babies should be postponed to reduce barriers by SSC and EIBF. Consideration should also be given to providing only medically necessary interventions during childbirth because some interventions such as epidural anesthesia and opioid pain medications can have implications for breastfeeding 41. Maternal epidurals and opioid pain medications have been associated with decreased adaptive breastfeeding behaviors in newborns and early breastfeeding cessation. Labor pain medications have also been associated with delayed onset of lactation (defined as lactogenesis stage II occurring >72 hours after birth), regardless of method of delivery. For women who require these pain medications, special attention may be needed to assist with the frequency and effectiveness of breastfeeding and to monitor the infant's hydration status if there is a risk of delayed onset of lactation. Minimizing medical interventions during labor and birth may help set the stage for uncomplicated breastfeeding 42.

Premature babies can attach to the breast, and suck after reaching 27 weeks of gestational age. Premature infants can start breastfeeding as soon as the baby's sucking reflex begins and the baby is stable.

Implementing the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative in conjunction with IYCF policies and programs is key to increasing the EIBF rate and preventing healthcare facilities from missing out on opportunities to counsel and support EIBF in prenatal care and delivery. Baby Friendly Hospitals are at a key point in the programming of breastfeeding starting from the prenatal period.

Regular training and practices containing up-to-date information about breastfeeding for mothers and health professionals should be supported by policy and administrators 43.

Currently, data on EIBF is not systematically collected in some countries, indicating that the importance of WHO recommendation for EIBF is not appropriately recognized. There is an urgent need to introduce the routine monitoring system of EIBF in all countries. The original Ten Steps, published in 1989, are grouped separately with "the first two steps that address the management procedures necessary to ensure consistency and ethics" and the "other eight steps". This will make it easier to monitor breastfeeding indicators, globally.

Mothers who cannot initiate breastfeeding within the first hour after birth should be encouraged to breastfeed as soon as possible, as it is more beneficial to start breastfeeding as early as possible due to the inverse duration-response effect. This should be considered for mothers-infants who have had a cesarean delivery or have a medical condition that prevents the initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour after birth ♣