Introduction

Although the concept of open regionalism (OR) has somewhat changed over time, it is currently a dominant feature of the Latin American regional integration initiative known as the Pacific Alliance (PA) -Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru-. This type of scenario aims for the strengthening of economic bonds between member States while also serving as a platform for better-quality commercial cooperation with third parties.

This article offers an analysis of the role played by the private sector in the regional PA integration initiative via the specific case of the SURA Group -a Colombian multilatina1 with tremendous growth and potential, which has businesses and economic interests in the four PA countries- and its dynamics therein. Consequently, the case study focuses on the research about how the Colombian private sector takes advantage of the structure offered by the PA. For governmental institutions and the productive sector, the PA is considered a good insertion mechanism towards the Asia Pacific region. The previous statement is based on evidence provided by different actors involved in the agreement.

Additionally, the article presents a historical overview of some proposals and mechanisms for regional integration in Latin America in order to identify the regional impact and scope of the PA. Given the article's extension, it is not possible to go beyond processes directly related to South America, which becomes a geographical limitation. However, it does not affect the central argument under analysis.

For this purpose, an extensive literature review was conducted in order to understand the historical evolution of the integration initiatives in Latin America. Besides, this article explores the repercussions some of these agreements have had for business interests. To complement these aims, the authors conducted several interviews with which they sought to grasp the real implications schemes like those the PA has in the concrete development of market opportunities for companies.

The paper is divided into four sections: the first one highlights the historical development of integration mechanisms2 during the last decades in Latin America; the second section explains the Pacific Alliance and how it works; the third section explains the role of the private sector within the Alliance, and, lastly, the specific case of the SURA Group illustrates the degree to which the private sector has utilized and has been affected by the PA.

The authors conclude that the PA is beneficial, as a whole, to the Colombian business sector and for international links with some regional actors. Also, results suggest this variety of agreement, based on the principle of OR, is appropriate and useful for obtaining better regional and international outcomes among private sector actors. Finally, the authors determined there is a need to strengthen academic research on this subject, which remains still embryonic.

Methodological aspects

This paper analyzes the OR approach inside the PA integration. To this end, the historical changes that Latin-American integration processes have witnessed are evaluated in order to understand how the recently created PA inhabits the OR principle. It resulted noteworthy during the literature review the lack of research about the importance of the private sector within the PA and its role inside the agreement.

This article is the product of a qualitative research in which primary and secondary sources were used. Firstly, a literature review was conducted, considering papers and books written about the historical development of Latin American integration mechanisms. At the same time, articles about OR and its implications for the region were analyzed. In this process, relevant texts from authors such as Quiliconi and Salgado (2017) and Ozaryún and Rojas (2013) were studied. Thereafter, different works on the PA and its trajectory were reviewed. Different publications regarding the role the private sector has in diverse regional mechanisms were considered. In addition, other secondary sources as magazines, newspapers, business reports and documents published by the PA were consulted.

It is noteworthy that, during the literature review, it became evident the lack of research about the importance and the role private sector has in the PA. The author's strategy was directly targeted towards important players inside that sector, basically, because as Silverman (2016) says:

those of us who aim to understand other's understandings choose qualitative interviewing because it provides us with a means for exploring the points of view of our research subjects, while granting these points of view the culturally honoured status of reality (2016, p. 53).

Consequently, this research used semi-structured interviews conducted by the authors, convinced about the meaningful information direct actors can supply. In this approach, observations gathered from academics and other personalities involved directly with regional integration were crucial as primary sources; the interviewee Diego Cardona, for instance, is both an academic and a practitioner regarding these topics. Besides, it is important to mention the interviews conducted with prominent businessmen such as Mario Hernández and Sergio Ignacio Soto, and executives of the SURA Group, including Ricardo Jaramillo Mejía, Vice-President of Corporate Finances, and Ignacio Calle Cuartas, SURA Asset Management President, aiming to understand the views the private sector and the aforementioned company have about the reach and impact the PA has had.

Open Regionalism and Its Historic Evolution

Latin American regional integration should not be confused with European or North American integration processes, given the pronounced regional differences in play. The current scenario, in each case, is clearly the product of a distinct and complex historical process. Nonetheless, the North American and European examples offer basic conceptual frameworks from which Latin American initiatives may be understood and adjusted.

Such adaptation is certainly apparent in the PA initiative, which promotes trade and incipient social integration via the free movement of people in a manner conducive to the particularities of the region.

Since the initiative is based on the concept of OR, we shall begin by briefly charting the genesis of that term.3 In this sense, this work requires a review as detailed as possible, regarding the historical perspective, on how regional integration has progressed on the road to the emergence of the PA as a singular instrument in this matter.

The concept of OR gained importance during the 90's when the Latin American and the Caribbean region were facing the new challenges of market liberalization and globalization.4 Some argue it was a natural outcome of the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP), suggested by the Washington Consensus,5 while others suggest it was a forced or coercive outcome, due -to some extent- to the failure of regional integration based on the previous ECLAC recommendations (Stiglitz, 2002; Toro, 2004).

Some would argue that OR obtained its quintessential expression in the activities, agreements, and discussions within the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC), established in 1989 (Bergstein, 1994). However, the forum did not seek to define OR nor explicitly utilize such terminology. Indeed, several years passed before a precise academic definition was offered. Bergstein (1994),6 synthesizing five possible definitions, suggested that "the concept represents an effort to achieve the best of both worlds: the benefits of regional liberalization, which even the critics acknowledge, without jeopardizing the continued vitality of the multilateral system."

Furthermore, he notes that many promoters of OR conceive it as a "device through which regionalism can be employed to accelerate the progress towards global liberalization and rule-making." Along these lines, he offers five possible conceptualizations: first, the notion of OR as an open membership in a regional organization (e. g., the PA);7 second, the existence of an unconditional most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment.8 The problems that normally arise with unconditional MFN constitute the third alternative, i. e., conditional MFN extension to specific agreements of liberalization. A fourth possibility would be to simply continue the reduction of barriers on a global basis while all members pursue their regional goals. Lastly, there is an analysis about the outcomes of changing the traditional view about this matter, which would entail simultaneous achievement of free trade in the region and the world. The result would again turn on the policy decisions of the members (Bergsten, 1997).

In the interest of offering a complete and useful definition of OR, it is important to further note Fernández and Hogenboom's (1996) characterization, based on ECLAC reports:

Open regionalism is the conceptualization of regionalization and globalization of the Latin American economy as one inseparable process. [It is] based on two pillars. First, it is based on growing economic interdependency at the regional level (...) Second, it is based on regionalization of national private capital elements that have been strengthened by the selling of public enterprises [sic.] (p. 4-5).

As previously indicated, both pillars are underpinned by a change in economic ideology within Latina America and the Caribbean. However, although regionalism as a concept was mainly developed during the 90s (at least by most thinkers and scholars), if understood as a mean towards defining necessary steps inside the Latin American integration processes, it is an older idea.

During the 70s, regionalism in Latin America was orchestrated under the auspices of import substitution industrialization (ISI), a protectionist model designed to avoid international competition in national markets (Rojas & Terán, 2016). During the same decade, the ECLAC led the implementation of the ISI model, centered on the desire to develop regional economies, which at the time were based on imports.9

As a basic definition, following Bussell (2018), the ISI model was intended to incorporate three key phases or steps: first, national manufacture of previously imported simple nondurable consumer goods; second, the extension of domestic production to a wider variety of consumer durables and more sophisticated industrial products, and, lastly, the exportation of manufactured goods and continued industrial diversification and specialization. Some Asian cases potentially show successful implementation of this process (Balassa, 1977; 1982).

Thus, the ISI model may be understood as an attempt to reduce foreign economic dependency by increasing internal production of industrial and manufacturing products. However, the model does not entail the elimination of imports since, when a country increases its industrial levels, it starts to import new materials in order to satisfy its requirements.

One relevant objective of the ISI model was to protect internal production sectors from external competition. Subsequently, "economic policy instruments such as quotas, tariffs, subsidies, and special licenses were applied to imports and exports" (Levy-Orlik, 2009, p. 436). Furthermore, some policies created to finance specific economic and social sectors were coercively enacted. States had total control. Therefore, the model could also be defined as a path whereby States increased their dominion over society.

According to Reinhardt and Peres (2000, p. 2), critics of the model argued that the ISI "was based on a misguided rejection of the basic principles of laissez-faire economics." As problems with ISI appeared, discussions regarding its advantages shifted their focus on Latin America where -after the implementation of the model-, industries and companies subject to it could only subsist through the rent-seeking made possible by protectionism and subsidies, which made them unable to compete in international markets. However, it is not appropriate to offer generalizations about the ISI model outcomes since some cases demonstrated different scopes.

According to Martinez (2016), two main events during the 80s influenced Latin American regional relations: the signing of the Single European Act and the Latin American external debt crisis with their well-known strong effects. Because of these events, governments in the region decided to reduce tariffs and open up to international trade. In addition, some evident problems associated with protectionism during its final stages in the region were noted by Levy-Orlik (2009):

The main problems of protectionist policies were: first, their generalization, including all manufactured goods for which there was internal demand, and thus protectionist policies were used to produce high-tech final goods. Second, protectionist policies covered domestic and foreign capital equally. There was no intention to build a national industrial core to develop and fortify backward or forward linkages. Finally, LA faced more difficulties in comparison to other developing regions because of the characteristics of the us economy, primarily low import capacity and a wide range of manufacturing that made LA industrial specialization more difficult (p. 448-9).

The 1990s brought a new variety regarding regional integration and cooperation known as OR: "The open regionalism model was based on the premise that unilateral trade liberalization was the key to enhancing more efficient participation of Latin American countries in the global economy through exports" (Quiliconi & Salgado, 2017, p. 17). Currently, some authors are speaking about new derivations and regional trends. However, that is not the concern of this paper.10,11

Based on the above trajectory, one might say that Latin American regional integration initiatives started long ago but not all were strong enough to reach the status of ratified treaties (Mace, 1988). The creation of the Latin-American Free Trade Association (LAFTA) in 1960 was intended to establish a common market in the region. It was created almost parallel to the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. In fact, LAFTA was substantially inspired by the EEC.

However, the development of these organizations followed very different paths. The political processes of regional integration in Latin America have indeed been far from stable.

Such instability is in evidence within organizations like the Andean Community (CAN, for its initials in Spanish), wherein political differences between member States (currently comprising Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, formerly including Venezuela)12 produced high levels of discord (Cordeiro, 2007). After numerous controversies and disagreements, Colombia and Peru effectively became a liberal faction on one side, while Ecuador and Bolivia became an opposing interventionist faction (Ahcar et al., 2013). In addition, Venezuela refused to participate in the organization because of its interest in joining Mercosur. Several authors (Malamud, 2006; Sainz, 2007; Sasaki, 2012) have also demonstrated that the Bolivarian government primarily defended its position by alleging Colombian and Peruvian unilateral free trade negotiations with the us and the European Union.

According to Blanco (2013), Andean integration has advanced as a matter of foreign policy that operates without consultation of society. Furthermore, integration is considered a political process and an outcome ensuing from governmental decisions. In this respect, Guerra-Borges (2001) pointed out that integration comprised of a set of political decisions taken by people, e. g., national strategic elites change every time the government changes.

Another instance worth briefly analyzing is Mercosur, which is theoretically a customs union between Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela (presently suspended), Paraguay, and Uruguay. Created in 1991, this community has recently been paying close attention to the development of the PA since it represents a challenge to its own status and accomplishments in the region. The development of Mercosur has been led principally by Brazil, and, as a result, there are complaints from small countries (Uruguay and Paraguay) of being ignored in the integration process.

As with CAN, Mercosur suffers from a lack of coherency among its member states. This is partly why it is so difficult to understand integration and regionalization processes in Latin America.13 Notwithstanding the general agreement to unify the region, shifting political and economic interests have slowed down Mercosur's progress and divided its member states. Such discord and intransigence have led Uruguay to explore membership possibilities in the PA (Mander, 2014), though full membership remains a somewhat distant prospect:

Last year, Danilo Astori, vice-president of Uruguay, which is Mercosur's least populated member and enjoys observer status in the Pacific Alliance, said he hoped his country would become a full member of the new bloc "as soon as possible". He criticized the "inaction" of Mercosur (Mander, 2014, p. 2).

Joining the PA would be a very difficult and complex process, moreover, requiring Uruguay to quit Mercosur, given that organization's restrictive regulations for its members; as such, it is not considered likely to enter the PA. Panama and Costa Rica, on the other hand, are official candidates for PA membership (Angeles et al., 2014), the latter candidacy being the most advanced.

Nevertheless, the goals of both associations, PA and Mercosur, are different. According to the official position, the first one aspires to an "insightful economic integration" (Alianza del Pacífico, 2012, p. 4), while the second one was inspired by the European Union (EU) and attempted to go beyond a basic common market. According to Mander (2014), Mercosur wanted to imitate the EU integration process to compete in a local and international arena. Now, based on this parallel review, it is not mistaken to say the PA -as a simple mechanism- is clearly challenging the previous Latin American regionalization processes.

By the first decade of the 2000s, the region started to develop what was called a post-hegemonic regionalism. According to Briceño (2013), however, the region remained highly fragmented during this period while hosting very different integration models. As stated by Martinez (2016), this phase of regionalism was also characterized by governments paying more attention to politics while leaving behind the economy and at the same time trying to create opposition to the us and its power over the region.

Such priorities are apparent in regional integration initiatives like La Alternativa Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra America (ALBA),14 which represented the views of the so called "Socialism of the twenty-first century," characterized by a general mistrust of capitalism, accompanied by growing attention to social issues like poverty and wealth distribution, at least in a rhetorical perspective.

Around 2007, concerns about the kind of regionalism predominant in Latin America spurred renewed approaches to balance the socialist wave in the region. Some governments, unwilling to engage with leftwing regimes' policies, also considered insufficient more liberal-minded regional agreements, such as the CAN, already in existence. Those concerns encouraged the first exchanges towards creating new forms of counterbalancing liberal integration: diverse discussions also reflected a growing desire to become commercially competitive as a region by thinking more globally.15

It was under these circumstances that the governments of Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru developed El Arco del Pacífico. The proposal was to design and boost a new regional power bloc exclusive of the sort of thinking expressed by Venezuela (which left the CAN in 2006)16 and Bolivia. The negotiating governments sought to join forces in order to reach global markets, especially in the Asia Pacific region (Morales & Sarracino, 2013).

According to Briceño (2010), the "Foro Arco," as it was also known, had three functions. First, it sought to defend the neoliberal policies initiated in the late 80s. Second, the initiative was a response to ALBA and its proposal to create a regional integration agreement against perceived capitalist and imperialist threats. Third, it was designed to facilitate regional negotiation with Asia Pacific countries -especially China- (p. 25). Unfortunately, differences regarding governmental policies and lack of commitment hampered the initiative.

In 2010, however, Peru, Colombia, and Chile (later that year joined Mexico) returned to the negotiating table. Finally, on April 28, 2011, the Pacific Alliance was born in Lima, Peru, via the Lima Declaration. According to Abusada-Salah et al. (2015), the first arrangement signed by the PA members was the Central Agreement17 of June 2012, which contains the rules and legal framework of the primary integrative arrangement: the second being the Additional Protocol, signed in February of 2014, commonly known as the commercial protocol.

The PA

As elaborated above, the PA was intended from the beginning to focus mainly on commercial integration and international cooperation. It is an open and non-exclusive integration initiative,18 which means that its members are not restricted from negotiating other types of commercial agreements with non-member states, being this characteristic a main feature of OR. According to Fernandez and Portes (1998, cited by Garzón, 2015):

In open regionalism, the ultimate goal of clustering the national markets of different states is less about fostering intraregional trade among them and more about forming a larger market that could prove more attractive for market-seeking investors from abroad by increasing both the latter's incentive to "jump" the regional agreement's external tariff (in the case of a customs union) and the economic viability of lumpy investments (p.15).

Nonetheless, it is evident the PA'S understanding that to be attractive to the world, it has to be internally strengthened. For this purpose, governments and different interest groups work together in country-members to build the cooperation required.

Within the foundational agreement (Acuerdo Marco), it is possible to identify diverse features of this mechanism. It is noteworthy the certainty governments expressed regarding the direct benefits of regional integration. This is why, considering the value OR and multilateralism have, and reinforcing the relevance of the WTO principles

for the OR dynamics,19 the four member States decided to settle clear rules intended to promote economic growth and market diversification, mostly convinced about the benefits of creating new bonds, especially with the Asia Pacific region.

In the same line of the PA objectives, all of them explicitly written in the Acuerdo Marco (article III), the path to build a deep integration area was drawn, intended to achieve the free movement of capital, goods, services, and people. To fulfill this objective, the PA has proposed to drive for higher growth, development and competitiveness within the economies involved. Based on it, all endeavors are being directed to become a political cooperation, economic and commercial integration, and a global reach platform under the premise of OR (Alianza del Pacífico, 2012). In response to this, the PA approved its Visión Estratégica 2030, a document in which it is undeniable the global perspective this mechanism has as well as its motivation for continuous improvement and development, looking into the future (Pacific Alliance, 2018).

In addition, it is remarkable how the PA members defend the existence, importance, and legitimacy of previous (and future) agreements signed between them as well as with non-member states. This means that for the PA, there is no inconsistency when members, pursuing economic liberalization and market opportunities, sign different agreements outside this mechanism. Thus, the interaction between the international organizations and the PA allows country members to achieve their goals.

An evidence of this is the round-business meeting held last year in Peru, aiming to give visibility to entrepreneurs and companies from country members seeking opportunities to create connections and generate incomes. Among the countries invited to this round were Singapore, Thailand, India, Japan, and China, among others. In addition to that, there have been three more virtual rounds during 2020 due to the Covid-19 Pandemic.20

Chile's head of State is currently the pro tempore President, atop a structure that includes a Council of Ministers, High-Level Group National Coordinators (from each country member), and a Technical Group. Besides these organisms, there are some working groups that function transversally, including the Business Council,21 the Inter-Parliamentary Commission, and the Council of Finance Ministers. The existence of 59 observant countries (as of 2019)22 also indicates the international relevance of the PA as well as the critical support such observers deliver. It is not common to find this support for a simple agreement. Thus, the PA intends to restore the principles of OR initiated during the 90s, which enable Latin American countries to create regional agreements and supplies a platform for reaching the global economic sphere.

Within the complex of integration agreements that exist in Latin America, the PA comes as a response from four countries to promote OR, seeking to advance the process of economic integration among them as well as their global outreach, overcoming the ideological divergence found within other regional groups (González-Pérez et al., 2015, p. 34). According to Quiliconi & Salgado (2017), PA members continued to defend OR principles and values, "whereas the countries that face the Atlantic, particularly in South America, have generally maintained their previous regional commitments while including new social agendas" (p. 23).

The PA initiative has three basic objectives: firstly, to create a consensual path toward deep integration and move progressively towards the free movement of goods, services, resources, and people. Second, it aims to drive growth, development, and competitiveness of the economies of its members while achieving greater well-being, overcoming socioeconomic inequality, and promoting the social inclusion of its inhabitants. Finally, it aims to serve as a platform for political articulation and global economic and commercial integration with an emphasis on the Asia Pacific region (Alianza del Pacífico, 2012).

Thus far, the PA has been interesting for business leaders, especially in a comparative position against other Latin American integration initiatives.23 Among the leaders on record in support of the PA is Maria Lloreda, former director of Invest Pacific (Coutín, 2014, p. 115). Lloreda notes that doing business, strengthening international cooperation, or promoting investments without institutional support has long been a complex task, which makes the PA a useful tool for trade expansion. At the same time, it enhances the political representation of countries like Colombia, which have minor institutional presence around the world (i.e., embassies, consulates, and other diplomatic offices).

Further highlighting the advantages of the PA, Villarreal (2016) points to numerous accomplishments in stimulating trade promotion, movement of people, and financial integration via the creation and unification of exports and imports offices, the removal of visa requirement for citizens of country members, and the increased investment flow among the four economies, associates, and observers. Ortiz (2017) ratifies this when she argues three essential elements the working PA has involved: convergence, interdependence, and identity.

Finally, it is worth noting the flexible and open framework of the PA, which differs from the "heavy" and slow configurations of some integration processes in the region such as the CAN or Mercosur. Moreover, according to Colombia's former president, Juan Manuel Santos, during the seventh Summit of the PA in Cali, the alliance is the "new driving force" of the regional economy due to its intention not to follow the previous integration models established. Thus far, members have reduced tariffs, created shared embassies in many different countries, and export promotion offices in Asia and Africa.

The Private Sector as a Fundamental Actor Inside the PA

The private sector as a significant actor for Colombian politics was first studied by Cepeda et al. (1964). After that initial research, there has been a reduced but interesting approach to the topic. As Garten (1997) observed, commercial interests have played a key role in foreign policy in Colombia and vice-versa. Giacalone (1997; 2015) and Rettberg (2002; 2007) have also made meaningful contributions to this topic. However, the whole attention to these issues remains scant. This means that a study such as the one presented here can be understood as relevant, insofar as it opens the path to new approaches between the private sphere and the PA in all its member countries.

Although substantial scholar studies exist on the relationship between the private sector and foreign policy,24 very little of these works pertain to Colombia. This paper is a contribution to the field because it offers an explanation about the role played by a specific actor of the private sector, taking advantage of the agreements arranged by the government in the execution of its foreign policy. It is relevant, especially when the entrepreneurs are aware of their role in promoting not only internationalization and cooperation but also the generation of productive chains. In a personal communication, the SURA Group's finances vice-president, Ricardo Jaramillo (2019), pointed out "the private sector plays a determinant role in encouraging the government to promote more agreements and better dynamics".

Among the limited knowledge of this topic in Colombia, we note Losada's work (2000) and its impact on the study of business associations as nodes of the private sector in Colombia. This author offers a detailed analysis of the Consejo Gremial Nacional,25 an association which comprises the main businessmen and industrial concerns in Colombia and which, in turn, has the capacity to influence the decisions of the Executive26 (Losada, 2000).

Additionally, Amaya (2013) studied the role played by the associations in the dairy sector in terms of influence within the FTA negotiation between the European Union and Colombia. His conclusion was that both the private sector and the associations in general have received little attention in the South American country over the last decades. Thus, one may conclude that, prior to the 90s, the public-private nexus was an issue of some importance for academics and researchers, but this interest was gradually lost.

As Amaya (2013) explains, the prolific production of texts from the 70s and 80s far exceeds what has been produced since the economic opening in the 1990s. Likewise, this limited production congealed around two lines of analysis: the first emphasizing the variables of a globalized and economic order, and the second arguing that the influence of the private sector waned in the face of State action (Amaya, 2013).

This second approach is controversial for some works referenced by Amaya (2013): the research of Echeverry (1987) and the one by Sáenz (1992). Some of these authors argue for the representation of productive associations by the same political and economic elites that became the owners of the State. Dix (1967) and Bagley (1979) similarly note the high interference of the private sector through productive associations. However, these works are now somewhat antiquated and, thus, do not necessarily reverse the trend suggested by Amaya (2013).

Junguito et al. (2015), citing Schneider (2004), specified that considerations regarding the interference made by the private sector in decisions related to public policies in Latin America are highly variable. In the Colombian case, such participation "tends to be typically formal, structured, known, and transparent and its actions are publicly recognized" (Junquito et al., 2015, p. 24).

In general, the research carried out on the relations between the private sector and the national government shows how before the changes generated by the economic opening, trade associations were considered relevant, and their level and capacity of interference remained high. However, with economic liberalization, the guilds gave an important ground that managed to administer satisfactorily the country's large economic groups (Rettberg, 2003). Thus, the large economic industry groups maintain an important position in their dialogue with the Executive, a relationship that transcends the dynamics of the PA.

Similarly, the private sector plays a key role inside the PA.27 In fact, from an economic perspective, it is impossible to imagine the PA without the encouragement of this actor. From the outset (Foro Arco), the mechanism has involved direct participation from the private sector within the four nations. Furthermore, the private sector has consistently expressed a high level of commitment to the negotiations. Many Latin American entrepreneurs (contrary to the twentieth century's situation) now demonstrate an interest in international economic affairs.28 The change promoted by the PA is relevant in this orientation.

In July 2018, the fifth business meeting took place during the Thirteenth Pacific Alliance Summit in Puerto Vallarta. Presidents Peña, Santos, Vizcarra, and Piñera participated along with several leaders of the productive sectors from each country. Again, their presence ratified the fact that the private sector is perhaps the most relevant actor among those involved in the advanced dialogues regarding the PA.

Although politicians' speeches in events, such as the one mentioned above, are often thought to contain little more than empty rhetoric and political correctness, empirical evidence29 corroborates the important role that the private sector has played in the PA dynamics (Benavides, 2018; Forbes, 2018). Its role in accompanying the governments in making advances in the technical and operative design has been remarkable. In the words of Martín Carrizosa, president of the Colombian chapter of the Business Council of the initiative (CEAP in Spanish: Consejo Empresarial de la Alianza del Pacífico), "entrepreneurs are the driving force behind the Pacific Alliance" (Portafolio, 2018).

Many political leaders have recognized the importance of the private sector for the PA. Furthermore, the Colombian former president and Nobel Prize, Juan Manuel Santos, emphasized in the aforementioned business meeting how, "to a large extent, the good results achieved by the PA are linked to the active participation the private sector has had," so far (Burgos, 2018).30 It is worth emphasizing how one of the lines of greatest interaction and collaborative work within the PA is the one with the private sector. It is increasingly common to find entrepreneurs from the four nations communicating with each other to advance their projects and processes in multiple sectors (Alvarez, 2018).

Inside the mechanism framework, the officials, leaders, and business interests31 of the four members stay connected through an exclusive instrument created for this purpose: the CEAP, in which every country has a chapter (PA, 2012). The CEAP is, thus, the group in which the interests of the major business people are represented and wherein they discuss agreements and new policies influencing PA members and their national enterprises.32

It is noteworthy how the PA is among the few regional association agreements that include such a council to hear and make decisions regarding the private sector ideas, needs, and proposals. This is important not only because it allows the private sector to generate policies and propose agreements that will benefit the members, but also because it plays a key role in the development of strategies regarding business with other countries around the world, one of the key features of OR.

An essential aspect to bear in mind regarding the aforementioned council is the invitation governments from the PA extend to the most prominent business people in their own countries, which guarantees the safeguard of the private sector interests. In addition to this relevant representation, the active involvement of the private sector creates a bond between economies inside the PA. The council has promoted agreements regarding competitiveness, homogenization of norms and regulations between members, technical requirements, trade growth, and liberalization, among other issues.

In addition, the council has worked to reduce taxes and double tax payment requirements on business between PA members. They have made great advances in this matter while achieving significant results regarding the financial integration promoted by the Latin American Integrated Market (MILA, for its initials in Spanish).33 Furthermore, new information technologies' innovations have been implemented in order to improve communication among entrepreneurs and businesspeople within the PA.

Consequently, it is not a mistake to define the role of the private sector inside the PA as crucial and dynamic, mostly if we consider some recent events. Currently, Ecuador is interested in joining this mechanism.34 The private sector representatives from the country have made remarkable efforts to generate a competitiveness agenda, framed in the dialogue with the private sector of PA members. In the same line, the Ecuadorian government is giving priority to this goal (Tapia, 2020).

Furthermore, last year, the XIV Cumbre Empresarial was held in Lima. It is important to highlight the significant progress concerning common policies about pension funds, double tax pay elimination, greater financial and fiscal integration, digitalization, and the fight against corruption. In this meeting, scheduled regularly before the presidential summit, the relevance the private sector has regarding the consolidation of common interests was displayed (Mellizo, 2019).

According to Ricardo Vega Llona, Peruvian businessman and former president of a relevant association in that country, the private sector and the presidents inside the PA conduct negotiations as pairs, which is a unique feature of this mechanism. He also pointed out the remarkable high levels of interaction between these two actors and how there is a clear win-win situation in all matters (Mellizo, 2019).

Lastly, in an interview conducted by Comercio Exterior to Sergio Contreras, a Mexican businessman coordinator in the PA, he pointed out:

[E]l avance más importante [de la AP] es el consenso privado con el que se ha realizado. En otras negociaciones de acuerdos de libre comercio, las consultas con los empresarios corresponden a los funcionarios públicos de cada país. En este caso, se extiende el ámbito de las negociaciones y, en conjunto, los empresarios formulan recomendaciones a sus gobiernos, lo cual propicia una dinámica diferente (Gándara, 2018, p. 62).

Considering this, it is possible to emphasize the certainty private sector representatives share about how important and crucial their role is to comprehend the realities of each economic sector. The interviews conducted throughout this research confirm this position in each one of the country members. Colombian businesspersons, for example, besides expressing their commitments with the dynamics of OR, have supported dialogue, interaction, and further agreements with the other country members.35

Furthermore, in reviewing business activities developed and supported by the PA, the role of the private sector becomes unquestionable. When analyzing internal advances (with external repercussions), business leadership is also evident. Even unpopular bureaucracies have been circumnavigated via the intervention of entrepreneurs, business groups, and economic (productive) associations.36

Thus, it is crucial to evidence the important role the private sector has inside the PA by exemplifying it with a real company. Moreover, the chosen firm was studied deeply in order to understand its real implications as a key player not only inside the Colombian market but also in the countries it has businesses due to its condition of multilatina. At the same time, it is relevant to understand how governments and the commitments they make as PA members concern the private sector.

SURA Group as a key player in the private sector

The SURA Group is one of the most important Latin American service sector companies. It is a firm based in Colombia with more than 70 years of experience. During its history, it has faced many challenges and has grown very fast over the last two decades due to several wise acquisitions in the region.

The 90s, for example, presented many new opportunities to the company, as with the spread of globalization, all companies faced the new scenarios such changes engendered. According to the official SURA Group website,37 in 1997, the company was named Compañía Suramericana de Seguros, but officials later decided to separate their insurance business from their investment portfolio, which led them to create Suramericana de Inversiones S. A. and Suramericana (the parent company). In the following years, the company consolidated its social security and investment portfolios.38 In 2008, even as the global financial crisis hit, the company began trading its shares in the over-the-counter (OTC) market in the United States, which represented a major milestone for the Colombian economy. However, it was not until 2009 that the company underwent a new structural change, after which the holding company was renamed Grupo de Inversiones Suramericana (Grupo Sura, as it is known today).39

The year 2011 was very important for the growth of the company and the development of new businesses in Latin America. It was then when the first steps regarding its consolidation as a multilatina began. According to an employee of SURA Asset Management,40 it was in 2011 when the company acquired the ING Group pensions and assets in Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, the largest acquisition by a Latin American company at the time. Later that same year, the company created their subsidiary SURA Asset Management in order to have a specialized group managing the assets of the recently acquired ING Group in Latin America and other business lines.41

The period from 2012 to 2015 witnessed the company's strong consolidation as a multilatina, with the SURA Group name becoming widely known in the region. By 2016, the company acquired the Royal & Sun Alliance Group (RSA) in Mexico, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, and Brazil; this purchase represented another strategic advance in the region through the acquisition of an important insurance group with many years of experience.42 As an interviewed employee stated, "SURA Group has known how to take advantage of specific economic situations that have happened in the world in order to make better acquisitions."

According to the information provided by another SURA employee,43 SURA Group has two main investment lines, classified as strategic investments and portfolio investments, the latter owning substantial shares of other important companies such as Argos Group and Nutresa Group (two of the biggest companies in Colombia). Regarding the strategic investments area, SURA Group has businesses in sectors including insurance, pensions, savings, and risk management. Additionally, their subsidiary SURA Asset Management (SAM) has operations in Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Uruguay, and El Salvador, which is the part of the company in constant involvement with the PA and its members. SAM has people working in every country they have investments, particularly in the PA member states. According to some interviewees, SURA Group has recognized the relevance of these specific markets inside the Latin American region.

The current organizational structure of SURA Group is framed in the graphic below:

According to the CEO of SURA Asset Management,44 SURA Group's internationalization process started in the 90s, but the agreements generated within the PA have been very beneficial for it, and the company is highly aware of how to take advantage of those agreements. It has also trained employees with respect to PA provisions. For instance, one of the most important agreements within the PA (of which, inter alia, SURA employees have been appraised) is the possibility for a parent company in one country to operate subsidiaries in another PA country with lower taxes, which allows the mobility of dividends.

As stated by an employee during an interview, "we are convinced of the opportunities the Pacific Alliance gives to the region; this is why SURA Group has been very interested in participating in the whole PA strengthening process." The company's former CEO also pointed out the importance of the commercial agreements fostered by the Chambers of Commerce from every PA country, which boosts the possibility to increase FDI among them.

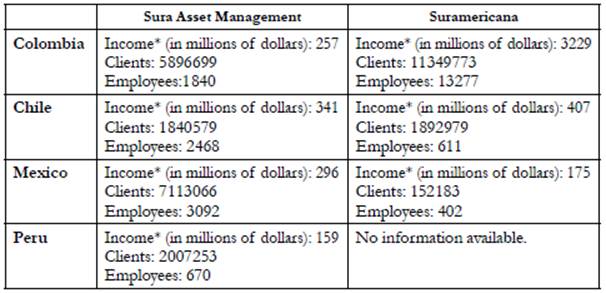

According to the SURA Group Annual Report (2017), the representation of the Company in the PA countries is substantial (Table 1).

Table 1 SURA Group basic information in PA member countries

* Income corresponding to commissions from companies AFP Protección and AFP Crecer (not the same method registered in the consolidated financial statements).

Source: compiled by authors from information provided by the Sura Annual Report (2017, p. 10).

For the SURA Group, the PA constitutes a significant market and substantial opportunities to grow in Latin America, which has been its main area of interest since the beginning of its expansion. Furthermore, the former President of SURA Group, David Bojanini, indicated in 2015, during an interview for a Latin American magazine, how SURA is trying to replicate the same business portfolio they have in Colombia in the rest of the countries in which it operates (Villahermosa, 2015).

As previously stated, pension funds are one of SURA Group's principal businesses. Within the PA region, pension funds are a rapidly growing market, which could offer substantial opportunity for SURA as market integration increases. Along these lines, one of the main goals of SURA Group in the PA is to develop the possibility of pension mobility among country members, i.e., the possibility for regional workers to move from one country to another without losing their existing pension savings.

There are also significant opportunities regarding financial systems within the PA member countries. For the SURA Group employees interviewed, the financial market in the region has not yet achieved its full potential, and many actions can be implemented to overcome informality and attract more clients willing to invest in the region, especially considering the growth potential. From this perspective, the vice-president, Jaramillo, says:

Although the motivation to enter those markets was not the existence of the Pacific Alliance itself, it helps today. As there are more initiatives towards further integration, we get more benefits. If there are double taxation agreements, we get benefits; if we accomplish more integration regarding financial services, we get benefits; if there is free mobility regarding pensions, we get benefits (personal communication, 2019).

SURA Group's efforts to avail itself from the full benefits of the PA have operated substantially through SURA Asset Management, which offers a regional vision for its clients. For instance, a Colombia-based company, which performs acquisitions in Chile and Mexico, can receive complete regional advice and investment management from SURA Asset Management. This is the key area wherein SURA Group is taking advantage of the PA arrangements. In this line, Jaramillo said:

We are proactive actors in fostering the Pacific Alliance agreements and their deeper integration, because we are convinced this represents a win-win situation for country members, not only for the economy, but also for the companies, markets, population, etc. (personal communication, 2019).

As the SAM CEO also revealed in 2018, they managed 140 billion US dollars for 19 million clients within the countries they operate, which represents an enormous amount of assets and clients for a Latin American company.

Nonetheless, challenges persist in the region, especially in light of the agreements an initiative such as the PA can deliver. According to the SAM CEO, three main topics remained at the top of the agenda for the companies participating in the CEAP:

Rules that allow worker's mobility (in terms of pensions) among the PA members.

Recently, there was a major milestone in the investment capabilities of the PA members, represented in the possibility granted to the pension funds of one PA member to invest in the stock exchange of another PA member.45 This proposal, however, still requires refinement and further engagement from the four governments.

The possibility for people located at one PA member state to buy stocks from another PA member stock exchange. This is directly related to the MILA (Mercado Integrado Latinoamericano) and efforts made to create an integrated market for current and future PA members.

These issues still require action from private sector representatives in the council. It is generally expected, however, that barriers to their implementation will be surmounted in collaboration with the four member governments.

Conclusions

Several conclusions may be drawn when analyzing the topics covered in this paper. First, integration processes vary greatly in Latin America. The historical voyage reveals serious difficulties in determining the most suitable model, scheme, mechanism, project, or initiative. At present, an updated and refined concept of OR has reemerged as a viable path through the implementation of the PA. Although authors have given different names to this type of integration, in reality, the PA remains fundamentally aligned with the notion of OR defined for the region during the period of structural adjustment programs (SAP) in the 90s.

Secondly, this work demonstrates the novelty and impact of the PA initiative in the region to ease regional integration. It may even be said that it has gradually become a challenging mechanism for Latin America, given its distinctive features and its substantial effects in such a short time. Hence, the agreement raises the question of what has been previously carried out with respect to regional integration in this part of the world, which at the same time can give some light about the flaws of other instruments. Likewise, the PA has provided a vehicle to non-state actors when seeking to influence economic policy and regional integration initiatives.

Along these lines, a third conclusion emerges. The private sector represents a key role inside the Pacific Alliance. As major players in country members' economies, the most prominent businessmen and businesswomen are essential to the development of economic policies and further commitments, not only inside the region but also boosting international projection -especially, in the case of the PA, with Asia Pacific countries. Moreover, the research conducted enabled the authors to conclude that the PA is at the same time very relevant for business interests in the country members, and the key actors inside this sector recognize this integration initiative gives them tools to enhance economic development and cooperation. These findings lead to another meaningful conclusion: the importance of strengthening research on the role of the private sector inside regional engagements like the PA. There is a lack of work regarding this topic, and further study would be beneficial, not just for the international business field but for the analysis of Latin American international relations.

Lastly, this paper analyzes how the SURA Group has taken advantage of the international agreements reached by the Colombian government. Not only has SURA strengthened its businesses in Colombia, but it has also developed a substantial network of subsidiaries and different business lines, in part, by taking advantage of PA provisions. The SURA Group is emblematic of companies throughout the region making effective use of international agreements originated in regional integration mechanisms, among which the PA stands at the forefront.