Introduction

The day after the 1988 Brazilian Constitution was enacted, a deputy from Rio de Janeiro presented an amendment bill proposing the death penalty.1 Despite the progressist mood of that time, the author was able to gather 185 signatures from his colleagues in support of his bill (20 more than needed).

Politicians like him are emblematic of the large sectors of the Brazilian right that have deep roots in the authoritarian past. Since the democratic transition, right-wing forces formerly associated with the dictatorship have maintained their political clout by electing large delegations to both chambers of Congress (Madeira, 2006). At the same time, conservative politicians have tried to avoid the right-wing label, a phenomenon that has been labeled the "abashed right" (Madeira & Tarouco, 2010; Power, 2000; Souza, 1988).

However, this shame seems to have faded in the xxi century, as more politicians name themselves rightists and conservatives, while the legacies of authoritarianism have faded away, and the former cadres of the authoritarian ruling party no longer represent a majority of rightist politicians (Câmara et al., 2020; Quadros & Madeira, 2018; Quadros & Madeira, 2020). Beyond the growth of political right in the legislature, the increase in right-wing supporters within the society (Rennó, 2020) suggests that there is public demand for a new right agenda. Brazilian right-wing parties would now be ready to appeal to voters, signaling, for example, their lawmaking efforts.

This paper describes how the Brazilian party system deals with the conservative agenda of the New Right, comparing constitutional amendment proposals from federal deputies of right and left, old and new political parties from 2001 to 2022. Selecting the xxi century allows for comparing proposals presented under governments from left and right, matching the two contrasting ideological waves in Latin America.

This research started with the expectation that the New Right agenda would be embraced by recently created right-wing political parties (those that emerged since 2001), showing an adaptation of the party system to new social demands. Findings like that would be reasonable given the increase of right-wing identification among voters in the same period already pointed out in the literature (Amaral, 2020; Singer, 2021).

However, the results indicate that the new Brazilian right-wing political parties are not the sole promoters of the New Right's constitutional agenda. Topics aligned with conservative issues have also been frequently addressed by parties across the ideological spectrum, including those from the left and center, new and old.

The main contribution of this paper is to show how the conservative agenda, which started in Brazil with the emergence of the New Right politics, has been integrated into the constitutional activities of a broad range of political parties. From right to left wing, federal deputies have proposed constitutional amendments to restrict rights and guarantees and toughen coercion provisions. Proposing constitutional amendments has been a way to advance this non-negligible demand in Brazilian politics and a way for legislators to indicate their stand.

The following sections describe the constitutional amendment process in Brazil, the social sources of the conservative agenda (the demand side), the Brazilian political and institutional context (the legislative dynamics and party system), and the conservative content of constitutional amendment proposals (the supply side). Quantitative analyses support the argument and lead to conclusions about the embrace of the conservative agenda by Brazilian political parties.

Amending the Constitution

Legislative behavior is a valuable proxy for measuring political positions, preferences, and ideologies. How representatives position themselves by proposing changes to the status quo (or opposing these changes) may indicate where their parties stand in the political arena. Beyond legislative voting, the content of legislative proposals may also reflect their parties' political agenda (Batista, 2020; Quadros & Madeira, 2020; Tarouco, 2007).

This research focuses on constitutional amendment activity rather than ordinary legislative activity due to its contents and the scope of its consequences. Amendments to the Constitution are particularly useful to get a grasp of parties' preferences and ideologies. Left-right and progressist-conservative cleavages appear more clearly in constitutional activities where there are opportunities to change (or keep) rights, duties, guarantees, and law-and-order provisions. Proposals of constitutional amendments also get more public visibility than lower-level bills and are instrumental in position-taking and credit-claiming strategies.

On the other hand, ordinary lawmaking usually refers to circumstantial policies where deputies may be freer to act strategically instead of ideologically. Brazilian deputies usually position themselves according to the government-opposition cleavage at the sub-constitutional level, rather than along the left-right dimension (Zucco Jr. & Lauderdale, 2011).

The Brazilian political system encompasses a presidential system, federalism, bicameralism, and open-list proportional representation. Each of these institutions spreads fractions of political power among multiple stakeholders (Horowitz, 2003) and creates several veto players (Ames, 2003). Beyond that, the Brazilian Constitution regulates a wide variety of issues, including extensive definitions of limits and duties regarding public policies (Arantes & Couto, 2010), making constitutional amendments necessary for every new government. That complex arrangement compels political actors to negotiate on nearly all issues and makes federal deputies especially interested in signaling their constituencies through legislative proposals on relevant matters.

Brazilian legislatures endure four-year terms, which coincide with presidential terms. Federal deputies are elected from multinominal districts corresponding to the 27 states, with magnitudes varying from 8 to 70 seats. Fragmentation is very high, with the Effective Number of Parties reaching 9,9 in 2022 despite having decreased since 2018. Legislative careers in Brazil are divided between regressive and progressive ambitions, leading significant turnover in the composition of the legislature with each election. This dynamic affects legislative behavior, with constitutional proposals serving as an essential feature.

From its enactment in 1988 until 2022, 3664 legislative proposals were made for Brazilian Constitution amendments. These types of legislative bills are called pec (Propostas de Emenda à Constituição) and usually the same pec addresses a set of articles in the Constitution regarding a given subject. This high frequency of amendment proposals points to the critical role of the constitution in Brazilian politics (Couto & Arantes, 2022).2

The targets of pecs are the 250 articles in the Constitution, organized in nine titles, each addressing a specific set of issues. There is also a final title called adct (Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias), with 114 more articles regarding interim regulations. Table 1 shows the pecs submitted from 1988 to 2022 according to their authors and the titles of the Constitution they address.

Table 1 Percentage of pecs by author and title of Constitution addressed from 1988 to 2022

| Author | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title of Constitution addressed | Chamber of Deputies (1) | Executive Branch | Senate | Total |

| 1) Fundamental principles | 0,2 | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,2 |

| 2) Fundamental rights and guarantees | 14,3 | 8,0 | 13,5 | 14,1 |

| 3) Organization of the state | 12,7 | 22,7 | 14,2 | 13,0 |

| 4) Organization of the branches | 27,8 | 12,0 | 23,7 | 27,4 |

| 5) Defense of the state and democratic institutions | 6,1 | 2,7 | 4,1 | 6,0 |

| 6) Taxation and budgeting | 12,7 | 18,7 | 14,2 | 12,9 |

| 7) Economic and financial order | 3,1 | 8,0 | 2,0 | 3,1 |

| 8) Social order | 13,7 | 9,3 | 10,8 | 13,5 |

| 9) General provisions | 1,8 | 1,3 | 0,7 | 1,8 |

| Transitional provisions, others (2) | 7,6 | 17,3 | 16,9 | 8,1 |

| Total (N) | 3441 | 75 | 148 | 3664 |

| (%) | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Pearson chi2(18) = 74,8427 Pr = 0,000

1) Includes 11 pecs from committees and 3430 pecs from individual deputies.

2) Includes 296 proposals on adct, one addressing every title and another that didn't mention any article, chapter, or title.

Source: the author, with data from https://www.camara.leg.br

Proposals from the executive branch address significantly more titles on state organization, economic order, and provisional issues than do deputies. Conversely, pecs from deputies address significantly more titles on branch organizations than those from the executive branch. The specific emphases of the executive branch reflect the huge reform agenda of all governments during this period (Couto & Arantes, 2008). Moreover, it is a consequence of the Brazilian policy-oriented model of the Constitution, which, beyond the classic fundamental provisions, norms, and principles, also regulates public policy design, goals, and budgets (Couto & Arantes, 2022). As for the emphases of legislators, it refers to recurrent attempts from deputies to reform political institutions such as the electoral system, length of terms, and re-election.

The conservative agenda of the new right: The demand side

Recent ideological transformations of societies worldwide have posed conceptual challenges to social sciences analysts. Political phenomena such as radical right, far right, conservatism, and populism, despite usually being empirically associated, must be kept theoretically distinct (Kaltwasser, 2023; Mudde, 2022; Rennó, 2023). The theoretical distinction between right-wing politics and conservatism is crucial for this paper's discussion. It is evident, for instance, in the classification of political parties from all over the world made by the Global Party Survey project (Norris, 2020).3 Table 2 shows how these two dimensions are not the same despite being associated. Conservative parties are also the majority among the left parties.

Table 2 Political parties in the world, according to left-right and liberal-conservative dimensions

| Liberal | Conservative | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left | 47,8% | 52,2% | 100,0% (n=488) |

| Right | 28,0% | 72,0% | 100,0% (n= 422) |

| Total | 38,6% | 61,4% | 100,0% (n= 910) |

Source: Norris (2020).

Pearson chi2(1) = 37,3831 Pr = 0,00

Right-wing politics and its supporters have historically changed in national contexts and over time. This paper is not about how extreme in the ideological scale is a right-wing party or how much they defy democratic rules. Instead, the focus is on the New-Right politics as a qualitatively distinct phenomenon that emerged in Latin America in the xxi century, resulting from the combination of an ultraliberal economic agenda and the conservative values wave. What justifies studying this specific manifestation of the right in Brazil is its recent coming to light after a long "abashed right" era (Power, 2000).

In the first years of the xxi century, Brazil saw the emergence of New Right politics, understood as follows:

A diverse set of individuals and organizations aiming to maintain societal hierarchies that are perceived as traditional or natural [...] Such hierarchies might include, for instance, patriarchy, the economic dominance of large businesses or landowners, or the subordination of LGBTQ+ individuals or Black and Indigenous Latin Americans. (Mayka & Smith, 2021, p. 3)

New right supporters have channeled their demands through a variety of social groups, from evangelical community churches to Internet platforms. Evangelical clergy usually mobilizes voters to support conservative candidates (Smith, 2019), who, after being elected, embody an influential interparty caucus inside Congress, the Frente Parlamentar Evangélica (Moddelmog & Santos, 2020; Santos & Moddelmog, 2019).

Rightist movements were also organized through online social networks and took the streets starting in 2013, initially protesting against all political parties and later demanding the impeachment of President Rousseff. Right-wing cyber activists extensively use digital media to spread political content, mobilize young Internet users, and rally virtually engaged crowds (Cavalcanti, 2021).

According to the literature on the New Right politics (Cowan, 2014; Cruz et al., 2015; Löwy, 2015; Mayka & Smith, 2021; Pierucci, 1987), it distinguishes from the traditional Latin American right by its opposition to the legacy of leftist governments. In contemporary Brazil, the content of its agenda varies among distinct groups of political actors who share the new right label. New Right voters and politicians oppose leftist parties because of their social and economic policies, corruption scandals associated with their governments, or their progressist values agenda.

During the military dictatorship (1964-1985), right politics were characterized by the fight against a communist threat. In the 1990s, neo-liberal governments emphasized globalization and privatization. Now, right-wing politics is no longer what it once was.

The so-called new right in Brazil comprises distinct advocacy streams. Inspired by moralist and religious discourses, conservatives aim to retrieve traditional values and hierarchies, reversing individual rights and guarantees such as those related to diversity and gender. The ultraliberals, in turn, claim to minimize state intervention in the economy, reversing redistributive policies, such as fiscal and social policies (Rocha, 2021). These two groups are similar in that they oppose changes in law and society promoted since the democratic transition, in addition to being proud of their right-wing and anti-left identities.

This paper focuses on the conservative agenda of new right politics instead of the ultraliberal agenda for two reasons.4 First, the conservative agenda introduces a new political dimension to the competitive landscape, whereas the ultraliberal agenda deepens the existing economic state-market dimension. During the first years of redemocratization, at the end of the twentieth century, the open defense of traditional moral order and repression of individual freedom would be displaced, while liberal reforms were already present in the 90s, in party platforms and government policies (Mainwaring et al., 2000). Second, each of these agendas finds its place in a distinct level of legislative activism. The conservative one deals with individual rights, guarantees, and freedom before public order and authority regulated in the Constitution. The ultraliberal agenda, on the other hand, may also be pursued through ordinary legislation and government policies that do not require to change fundamental provisions.

Conservatism fights policies and reforms made by left-wing governments, glorifies the past, and defends old morality against cultural change. Brazilian conservatives' agenda includes harsher laws to fight crime and reversing human rights and guarantees such as those related to protecting social minority groups, their rights, and full participation in politics and society.

From a theoretical perspective, new right politics appear in the scholarly debate either as a branch of the general right (Quadros & Madeira, 2018) or as a wing of an independent dimension (progressist-conservative) that crosscuts the left-right axis in a two-dimensional plane (Tarouco & Madeira, 2013). This paper reinforces the second view as the conservative agenda was pursued in pecs by parties from left to right.

Brazilian right-wing political parties: Old and new

Until the end of the twentieth century, support for the military dictatorship defined the political right in Brazil (Madeira, 2006; Power, 2008; Power, 2000). However, as the political arena resettled around PT and PSDB, several political parties tried to disguise their roots in the past regime, changing their names and moving to the center, "abashed" of their authoritarian heritage. Aside from the rebranded old right-wing parties, new political parties have emerged since 2001, seizing permissive rules that have further fragmented the Brazilian party system. Most of these novel parties started on the right wing of the ideological dimension (Maglia, 2020).

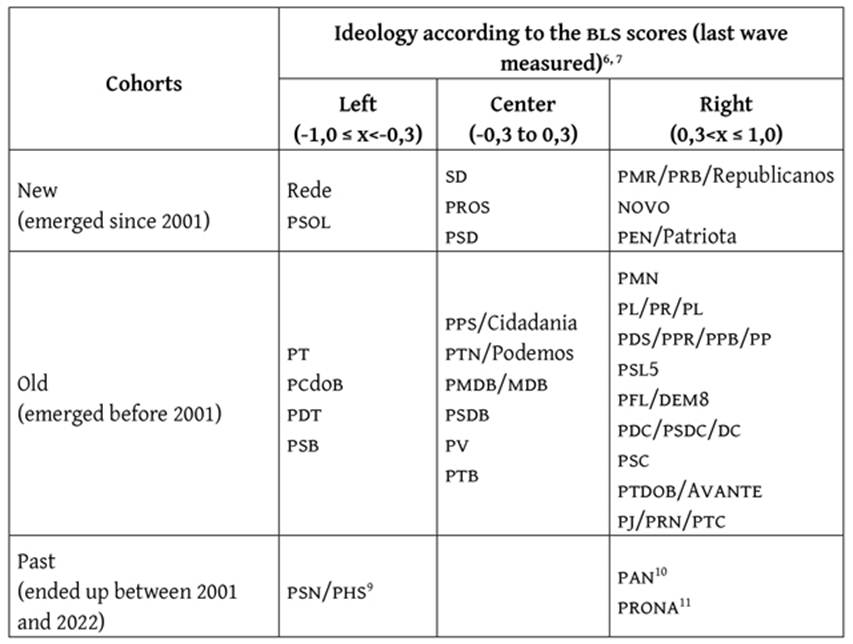

Parties' positions along the left-right dimension, shown in Table 3 are here measured using the Brazilian Legislative Survey - bls (Zucco & Power, 2024) scores.5 There are several other ways to measure party ideology (Tarouco et al., 2022). However, most Brazilian parties converge to the same relative order from left to right, despite the reputation of the inconsistency of the Brazilian party system.

Table 3 Brazilian political parties whose deputies submitted pecs from 2001 to 2022, by cohort

Source: the author, with data from Zucco and Power (2024).6 7 8 9 10 11

Almost one-third of Brazil's 27 current political parties with legislative seats are brand-new, having emerged since 2001. According to the bls scores, less than half of them are at the right of the ideological dimension, being, therefore, simultaneously newcomers and right-wing. Still, not all of them fit the concept of new right presented above. 12 On the other hand, many old right-wing parties have changed their names in the last 20 years. It seems that the political right has been renewing itself in Brazil, perhaps in response to the success of left-wing parties, perhaps following world trends.

Political parties and the Constitution: The supply side13

How does the institutional party system respond as new right politics emerges from society? Which political parties embrace its conservative agenda? The theoretical expectations that right-wing parties created in the post-2000 period would assume this task are not supported by data on constitutional amendment proposals.

Table 4 lists the specific chapters of the Brazilian Constitution that have been subject to conservative amendment proposals.

Table 4 Articles of the Constitution regarding the conservative issues

| Articles (filter 1) | Subject | New right issue targeted | Conservative change content (filter 2) | Conservative proposed changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 4 | Fundamental principles | Rights and guarantees | narrower than the status quo | 5 |

| 5 | Individual and collective rights and duties | Rights and guarantees | narrower than the status quo | 37 |

| 127 to 135 | Positions essential to Justice | Law-and-order | harsher than the status quo | 14 |

| 136 to 141 | Emergency provisions (state of defense, state of siege) | Law-and-order | harsher than the status quo | 1 |

| 142 to 143 | Armed Forces | Law-and-order | harsher than the status quo | 29 |

| 144 | Public security | Law-and-order | harsher than the status quo | 126 |

| 226 to 230 | Family | Rights and guarantees | narrower than the status quo | 38 |

| 231 to 232 | Indigenous people | Rights and guarantees | narrower than the status quo | 21 |

| Total | 271 |

Source: the author.

Proposals for constitutional changes targeting these articles, either to narrow the rights or to harden the law-and-order provisions, were coded as a pro-conservative new right agenda. To identify both rights narrowing or law-and-order hardening, each proposed change was compared to the constitutional status quo, that is, the target articles in the Constitution as they were in force at the moment of the pec's introduction. Amendments in articles on rights and guarantees (such as those related to diversity, gender, sexuality, religion, race, and childhood) would narrow them, while amendments in articles on law and order would harden punishment, control, and coercion.14

Some examples of these changes include several proposals for reducing the minimum age for criminal responsibility (allowing teenagers to be arrested), asserting that every life must be protected from conception (forbidding abortion), expanding police powers (extending public security attributions to municipal guards and the army), and undermining indigenous people's protection (making it easier to bypass their formal guarantees).

These changes have been proposed by the deputies of several parties, from right to left-wing. The proportion of these conservative new right changes among all proposed changes serves as a proxy for their saliency in the parties' constitutional agendas. Table 5 shows the distribution among parties.

Table 5 Conservative changes in pecs, by federal deputies from 2001 to 2022, according to their political parties

| A | B | C | C/B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | PECs | changes (articles) | conservative changes (n) | Conservative changes (%) |

| PMDB/MDB | 313 | 581 | 49 | 8,4 |

| PFL/DEM | 218 | 382 | 37 | 9,7 |

| PL/PR/PL | 162 | 353 | 28 | 7,9 |

| PDS/PPR/PPB/PP | 148 | 293 | 26 | 8,9 |

| PSDB | 280 | 438 | 24 | 5,5 |

| PT | 322 | 582 | 19 | 3,3 |

| PDT | 147 | 226 | 16 | 7,1 |

| PSB | 133 | 209 | 15 | 7,2 |

| PTB | 103 | 221 | 13 | 5,9 |

| PSC | 52 | 82 | 9 | 11,0 |

| PSD | 72 | 103 | 8 | 7,8 |

| PPS/Cidadania | 81 | 121 | 6 | 5,0 |

| PMR/PRB/Republicanos | 38 | 51 | 4 | 7,8 |

| PTdoB/Avante | 13 | 17 | 3 | 17,6 |

| PROS | 13 | 19 | 3 | 15,8 |

| SD | 20 | 35 | 3 | 8,6 |

| PV | 33 | 48 | 3 | 6,3 |

| PTN/Podemos | 24 | 35 | 2 | 5,7 |

| PCDOB | 59 | 79 | 2 | 2,5 |

| PSOL | 8 | 9 | 1 | 11,1 |

| PSL | 12 | 37 | 0 | 0,0 |

| REDE | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0,0 |

| PDC/PSDC/DC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,0 |

| NOVO | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,0 |

| PMN | 5 | 39 | 0 | 0,0 |

| PJ/PRN/PTC | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0,0 |

| PEN/patriota | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0,0 |

| NoPartyDeputies/Past parties deputies15 | 16 | 22 | 0 | 0,0 |

| Total | 2284 | 4000 | 271 |

Source: the author.

The center party MDB proposed conservative changes more frequently than other parties. However, PSL, DC, and Novo (right-wing parties) did not propose any of these changes. Another piece of evidence against theoretical expectations is the saliency of the conservative agenda (column C) in the whole set of changes proposed (column B). Among the only nine articles addressed by PSOL, a far-left party that originated from a schism in pt in 2005, there was a proposal to include in the Constitution the statement that "all the power comes from God".16

The proportion of conservative changes relative to all proposed changes in constitutional articles (column C/B) clearly distinguishes political parties from one another. That distinction shows how important the conservative agenda is for each party, reflecting how much emphasis they place on it in their constitutional proposals. That proportion serves as a proxy for the saliency of the conservative constitutional agenda and can vary from 0 to 100 for each party.

Methods and data analysis

The empirical strategy applied to approach how the Brazilian party system has embraced the conservative agenda is the correlation between the saliency of conservative amendment proposals and the left-right position. The unity of analysis is the political party each year.

The left-right position is taken from the Brazilian Legislative Survey (Zucco & Power, 2023). The saliency of the conservative agenda is measured for each party in each year as the proportion of conservative changes relative to the total constitutional amendment activity. The conservative changes embodied in each constitutional proposal were manually coded according to two filters: the chapters of the constitution targeted (if they refer or not to typical concerns of conservative agenda) and the direction aimed in the amendment proposal (if reinforcing or loosening the conservative content).17

That way of measuring saliency aligns with the approach used in the literature on party manifestos. The saliency theory (Budge, 2015; Robertson, 1976) argues that political parties compete by emphasizing distinct subjects according to their specific advantages or weaknesses in each area. The distinct emphases are measured through the amount of text dedicated to each subject by each party in their platforms. This way of measuring saliency allows comparing parties by the proportion of any agenda in their proposals.18

As the data comprise more than 20 years and six legislatures, and Brazilian parties move along the left-right scale over time, the next step is to compute the proportions of conservative changes for each party each year. Thus, the measure accounts for changes in the status quo and party priorities. The average saliency among the 308 unities of party/year is 11,8 %, varying from 0 (as 136 cases of party/year points) to 100 % (as sd in 2013 and 2016, PTN/Podemos in 2002, PRB/Republicanos in 2013 and psc in 2019).

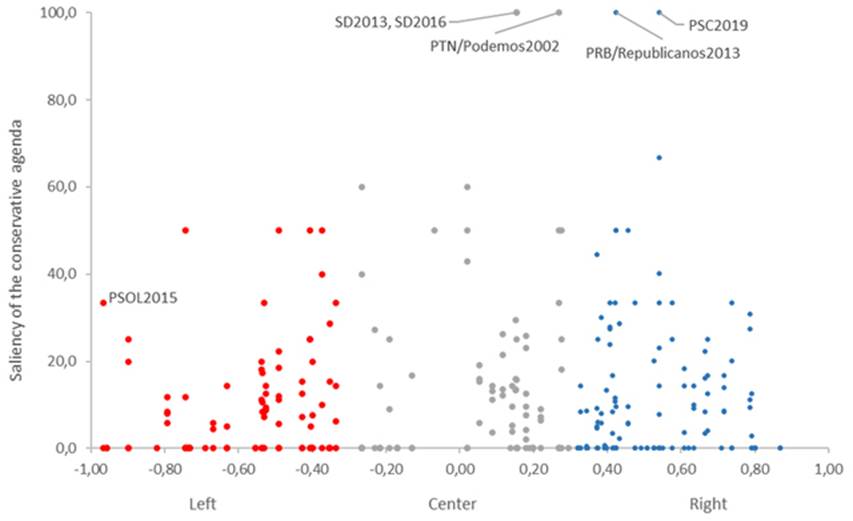

Figure 1 shows Brazilian political parties each year according to their positions on the ideological scale19 and the saliency of conservative agenda in pecs, measured as the percentage of conservative changes out of their yearly constitutional activity.

Source: the author.

Figure 1 Parties/years according to ideology and salience of conservative agenda in deputies' pec from 2001 to 2022

In the upper-right quadrant, we observe parties whose deputies, in specific years, exclusively focused on conservative changes in their pecs. However, there are many more right-wing parties whose interest in those issues is as low as the left-wing parties. Additionally, the center and left-wing parties reached 50 % of the emphasis on conservative changes, as much as their right-wing counterparts. As for the parties' constitutional activity, conservative and left-right dimensions are independent, as the Pearson test shows.

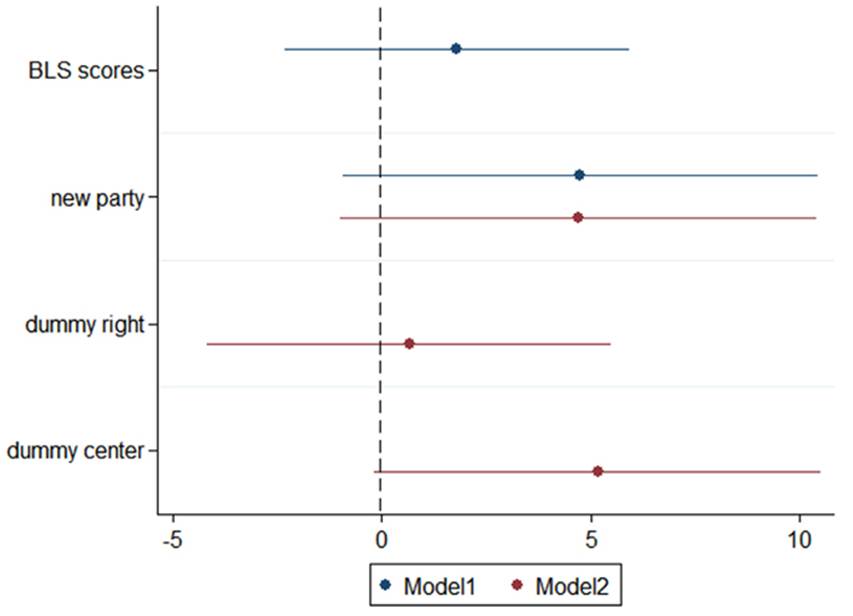

The new parties (those created in the xxi century) are dispersed throughout all the quadrants. Among those five parties with 100% pecs seeking conservative changes, only two (SD and PRB/Republicanos) appeared after 2001. The regression results in Table 6 and Figure 2 confirm that the saliency of the conservative agenda is not related to ideology or new-entrant parties.20

Table 6: Linear regression: Saliency of conservative agenda (% of conservative changes in pecs)

| Model 1 (Saliency) | Model 2 (Saliency) | |

|---|---|---|

| bls scores | 1.805 | |

| (2.098) | ||

| new party | 4.746 | 4.705 |

| (2.887) | (2.894) | |

| dummy right | 0.658 | |

| (2.453) | ||

| dummy center | 5.168 | |

| (2.707) | ||

| _cons | 10.95*** | 9.384*** |

| (1.111) | (1.899) | |

| N | 308 | 308 |

| R-sq | 0.012 | 0.024 |

Standard errors in parentheses * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001

Source: the author.

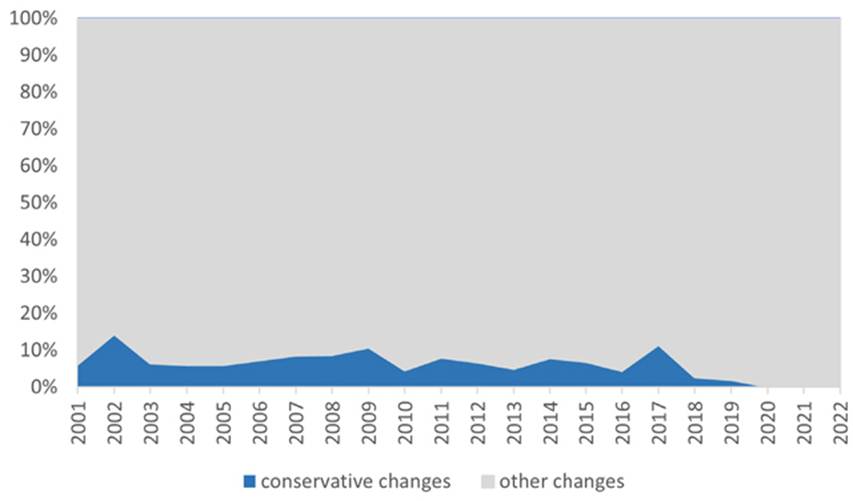

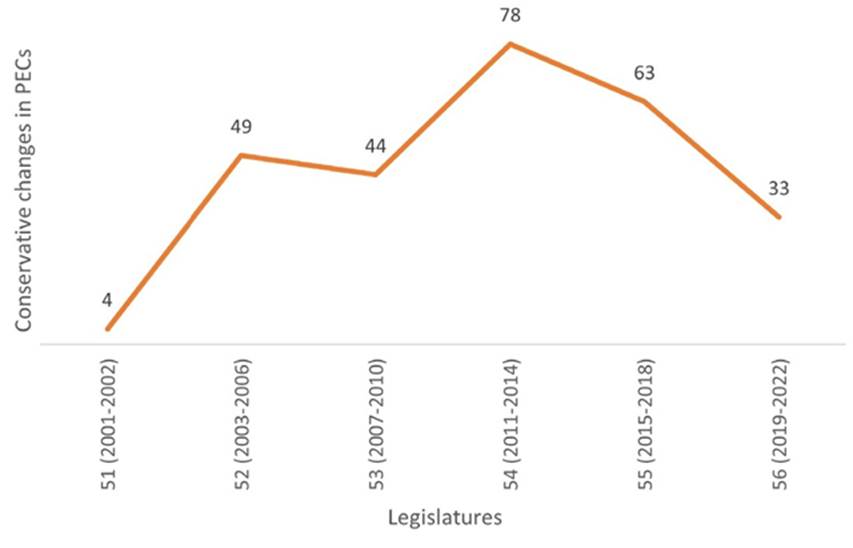

Surprisingly, the conservative agenda appeared more frequently in pecs submitted before 2018, when Bolsonaro's party (psl) elected many federal deputies. This puzzle may be attributed to several factors: i) the focus on blocking progressist pecs over the strategy of proposing conservative ones, ii) the focus on lower legislation levels over amending the constitution; and iii) the change in status quo by previous amendments. Figures 2, 3, and 4 show these variations over time.

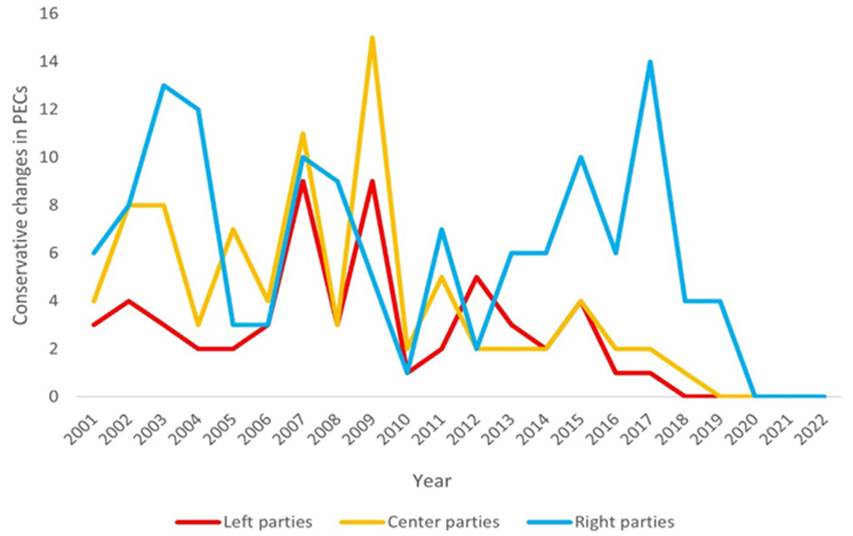

Beyond the variation over time, the frequency of conservative constitu tional changes proposed yearly varies among ideological blocks. Figure 5 shows cycles of pec with conservative content, differentiated by ideology. Deputies from right-wing parties proposed conservative changes at the beginning and the end of the period, while the center and left parties concentrated their activity around 2009. A possible reason for this variation is how each block of parties sees the status quo, which changes dynamically as amendments are approved.

Ideological blocks according to the categorization of bls scores (last wave available) in Table 2: left = (-1.0 s x<-0.3); center = (-0.3 to 0.3); right = (0.3<x s 1.0). Articles of the Constitution targeted in pec by deputies from 2001 to 2022 excluding 22 in pecs with no party (n=3978). Source: the author.

Figure 5 Conservative changes in pecs by ideology and year

For over twenty years, right-wing parties have submitted less than half of the conservative changes proposed to the Constitution. At some points, they even lagged behind the left-wing parties (2009 and 2012).

Conclusion

Proposing amendments to the constitution is an important activity performed by the deputies of all political parties. Constitutional changes that fit the conservative agenda are pursued through pecs, from left to right parties, old and new. As public demands became evident, politicians addressed them by presenting constitutional amendment proposals to their constituencies.

From 2001 to 2022, conservative saliency in constitutional changes did not distinguish the recent right-wing political parties. There is a consistent and visible conservative agenda in Brazil, but it is not exclusively driven by new right-wing parties. The novelty of a right-wing political party does not allow tracking the saliency of the conservative agenda in its constitutional activity.

Findings confirm that conservatism and rightism are not the same. Instead, they belong to two distinct dimensions of political competition space that cross cut each other. Constitutional amendment proposals in Brazil show that the party system has welcomed the conservative agenda and that political parties abstain from filtering the content of their members' proposals.

These results suggest that Brazilian legislators in the xxi century were no longer abashed to propose conservative changes. The ideologies of these parties do not prevent them from taking credit for advancing the rising conservative agenda. This paper found evidence that these legislators may come from any political party and work according to the institutional legislative book.

At the end of the twentieth century, Mainwaring and his coauthors (Main-waring et al., 2000) referred to conservative parties in Brazil as equivalent to right-wing parties, emphasizing their liberal economic agenda. At that time, the authors described conservative parties according to their programmatic bases, in which moral issues were addressed only briefly. The regime transition increased the presence of rightist parties in the competitive arena and warned of the risks they represented to the improvement of Brazilian democracy.

More than 20 years later, concerns about democracy have resurfaced, with the main threat now being attempts to retrench fundamental rights and guarantees and to harshen law-and-order provisions. This time, the risks come from legislators advancing that agenda through their constitutional amendment proposals. This study on pecs cannot fully capture the threat the Brazilian new right poses to democracy. Still, it may illustrate the extensive institutional ways for advancing its agenda and the low partisan hurdles in Brazil.