Although bats mainly use echolocation to move in their environment, they can use signals for orientation and movement (Suthers and Wallis, 1970), so visual organs are highly functional, even if they are small and with limited vision (Müller et al., 2009). It has been reported that, during the search for food and new refuges, vision aids in predator avoidance and, in some species, in the capture of prey (Altringham and Fenton, 2003; Eklöf and Jones, 2003), including the detection of flowers that reflect U.V. rays for those that feed on nectar (Winter et al., 2003).

Ocular abnormalities in bats have been scarcely reported (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). Some of the ocular lesions observed include corneal opacity, anophthalmia, microphthalmia, and bacterial infections (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). Recently, Turner et al. (2021) listed a series of ocular diseases in species of the family Pteropodidae, where corneal opacity leads, followed by cataracts, anterior uveitis, adnexal diseases and glaucoma. The most common causes of these diseases are trauma from interindividual and intraindividual aggression and falls or shocks during flight, which may be linked to underlying diseases that cause weakness (Turner et al., 2021). Other causes of these diseases are genetic predisposition, degenerations and environmental factors (Davidson and Nelms, 2013). Even in a study of ocular lesions in mammals, it is evident that the rabies virus extends to the eye, possibly through the ocular nerve (Dalton et al., 2020). Therefore, this would be another cause of ocular abnormalities in bats, as they may be reservoirs of the rabies virus (Scheffer et al., 2014).

The infrequency and scarcity of reports on the subject may indicate that it is not given the required importance or that cases go unnoticed for various reasons such as the small size of the eyes of some species (Sánchez-Hernández et al., 2019). The importance of reporting these anomalies in bats, whether in their eyes or another part of the body, marks a milestone in terms of studies on mortality due to diseases and their possible causes, and in turn is of utmost relevance for the study of ecosystem health (Bayon et al., 1999; Turner et al., 2021).

The objective of this report is to present the first case of ocular anomaly in Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Republic of Panama. Since it is a product of an unexpected observation during the development of the main study and we do not have the necessary materials for an adequate sample collection for any veterinary analysis, we cannot hypothesize about possible pathological or genetic causes of the anomaly.

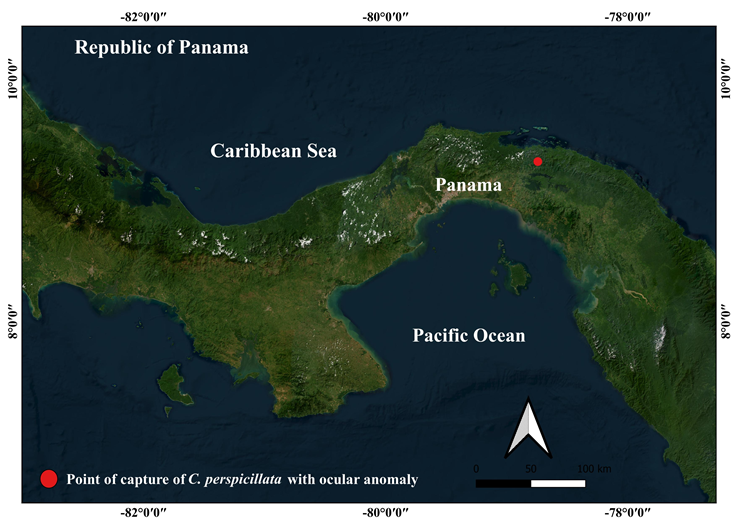

On February 9, 2023 in the Bunorgandi Private Nature Reserve (Figure 1) located in the Corregimiento de Cañitas, Chepo District, Province of Panama, Republic of Panama (9˚14̍ 53̎ N 78˚45̍ 09̎ W) of 53 individuals and 18 species, an adult male individual of C. perspicillata that presented an ocular anomaly was captured (Figure 2). The individual was captured at 19:55 hours using mist nets and identified using the guidelines of Reid (2009) and York et al. (2019). The individual presented swelling of the right eye globule and a small yellow coloration within the eye globule, which we assumed to be sightless as it did not respond to visual stimuli such as white and yellow light from flashlights, and proximity of objects. However, the left eyeball presented apparent normality, functional vision and responded to visual stimuli. Once the individual's data was recorded, it was released near the capture zone.

Figure 1 Capture area of C. perspicillata with ocular anomaly in the Bunorgandi Private Nature Reserve, Republic of Panama.

Figure 2 Individual of C. perspicillata captured in the Bunorgandi Private Nature Reserve with ocular anomaly in the right eyeball.

There are few records of ocular lesions, anomalies or diseases in bats, currently restricted to a few species in only five reports (Table 1).

Table 1 List of ocular lesions, anomalies or diseases recorded in bats.

| Species | Eye injuries or diseases | Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yangochiroptera | |||

| Eptesicus fuscus | Closed eyelids, unpigmented choroidal layer, undifferentiated retina and underdeveloped crystalline lens. | United States | Kunz and Chase (1983) |

| Carollia perspicillata | Blindness. | Brazil | Feijó et al. (2018). |

| Artibeus planirostris | Corneal opacity. | ||

| Artibeus lituratus | |||

| Artibeus jamaicensis | Corneal opacity, ocular injury. | Mexico | Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019). |

| A. lituratus | Corneal opacity, Active infection with subconjunctival hemorrhage, Anophthalmia. | ||

| Desmodus rotundus | Ocular infection. | ||

| Glossophaga soricina | Anophthalmia. | ||

| Sturnira parvidens | Ocular injuries with corneal perforation in the eye. | ||

| Tadarida brasiliensis | Microphthalmia or nanophthalmia. | ||

| T. brasiliensis | Ocular injury (non-specific). | United States | Dalton et al. (2020) |

| Myotis lucifugus | United States | ||

| Yinpterochiroptera | |||

| Pteropus vampyrus | Lens dislocation, cataracts, glaucoma, anterior uveitis, corneal disease, adnexal diseases (conjunctivitis, blepharitis, meibomianitis and partial tear of the lateral rectus muscle) and orbital diseases (retro bulbar abscesses, orbital fractures and acute traumatic proptosis. | United States | Turner et al. (2021) |

| P. pumilus | |||

| P. hypomelanus | |||

| P. giganteus | |||

| P. rodricensis | |||

| Cynopterus brachyotis | |||

| Rousettus aegyptiacus | |||

The little information available on eye injuries and diseases in bats generates several questions about how the lack of vision, which is complementary to echolocation signals (Feijó et al., 2018), affects the species in the wild to fulfill their functions of orientation, feeding and movement at short and long distances (LaVal and Rodríguez, 2002). Therefore, promoting reports of this type helps to gather information that can allow generating a basis for future studies more focused on analyzing the causes and consequences of ocular anomalies, injuries and diseases.