INTRODUCTION

Complex courtship behaviors with different types of male-female interactions have been described for Neotropical frogs over the past decades (e.g., Zina and Hadd-ad 2007, Nali and Prado 2012, Silva et al. 2014, Faggioni et al. 2017). These courtships are characterized by a combination of acoustic, visual, and tactile stimuli. Acoustic stimuli comprise advertisement and courtship calls (sensuToledo et al. 2015), the latter of which are emitted in close encounters among males and females (Lima et al. 2014, Zornosa-Torres and Toledo 2019). Tactile and visual stimuli include, for instance, male or female touches (Zina and Haddad 2007), holding of hands (Centeno et al. 2015), bites (Silva et al. 2014), bumping (Ovaska and Rand 2001), vocal sac displays, movements with limbs, and head and body postures (Starnberger et al. 2014, de Sá et al. 2016, Faggioni et al. 2017). However, these observations are rare (Köhler et al. 2017) and likely comprise only a fraction of the complex behaviors that may actually exist among the highly diverse Neotropical frogs (Pyron and Wiens 2013).

Courtships with complex signals are known in Bokermannohyla, a Neotropical tree frog genus with 30 species (Nali and Prado 2012, Centeno et al. 2015, Frost C2021). In Bokermannohyla ibitiguara (Cardoso 1983), a gladiator tree frog endemic to the Cerrado of Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil, the courtship can last for up to 60 minutes (Nali and Prado 2012). Males typically call perched on the vegetation, but oviposition sites or nests are small, concealed water-filled depressions outside the main body of water or other hidden sites on the stream bank, such as holes or rock crevices (Nali and Prado 2012, R. C. Nali, pers. obs.). During the courtship, the female follows the male to the nest while he emits courtship calls. Right before presenting the nest to the female, the male slaps the female on the side of her body and she follows him to proceed with nest inspection (Nali and Prado 2012). Although courtship calls were previously heard, they were neither recorded nor described for B. ibitiguara (Nali and Prado 2012), a species considered as Data Deficient, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature -IUCN (Caramaschi and Eterovick C2004). Descriptions of this type of call are extremely rare for the genus, available only for B. nanuzae (Bokermann and Sazima, 1973) and B. luctuosa (Pombal and Haddad, 1993) (Lima et al. 2014, Zornosa-Torres and Toledo 2019).

Herein we describe the courtship call of B. ibitiguara and provide further details of the mating behavior observed in an artificial environment. Moreover, we report on clutch characteristics and compare advertisement and courtship calls emitted by the same male to check whether specific acoustic parameters vary, further corroborating the ability to modify call parameters in this species (Nali and Prado 2014a).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Field work was conducted at the Serra da Canastra National Park, municipality of São Roque de Minas, Minas Gerais State, southeast Brazil (GPS coordinates: 20° 13' 38" South, 46° 36' 59" West, datum WGS84, 1339 m), during five nights in January and February 2013. The park is located within the Brazilian Cerrado, characterized by savanna-like vegetation, and observations were made in a typical breeding site for the species, a stream covered with riparian vegetation (Nali et al. 2020).

We searched for individuals at the breeding site guided by male vocalizations and observed their behaviors using focal-animal sampling, all occurrences sampling, and sequence sampling (Altmann 1974). We recorded advertisement calls using a Marantz PMD 660 digital recorder with a Sennheiser ME66 unidirectional microphone at approximately 1 m from the male. Recordings of the courtship calls were made using the same equipment but closer to the male (<50 cm), since this type of call tends to be less intense (Wells 2007, Toledo et al. 2015). We made video recordings with a Samsung ES25 digital camera (12.2-megapixel resolution), from which we extracted audio WAV files to measure additional courtship calls (e.g., de Sá et al. 2016). We measured air temperature and relative air humidity with a thermo hygrometer. Individuals were collected, measured in the snout-vent length (SVL) with an analogical caliper (0.05 mm), anesthetized and fixed according to McDiarmid (1994), and deposited at the Coleção de Anfíbios Célio F. B. Haddad (CFBH), Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil. We fixed the egg clutch with formalin 5 %, counted all eggs, and measured egg diameter and gelatinous capsule diameter under a stereomicroscope Leica S8APO with a digital camera Leica DFC295 and software Leica LAS Interactive Measurements.

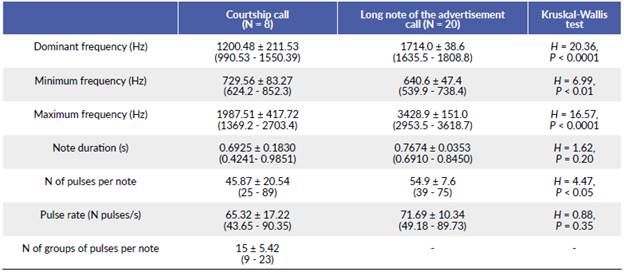

We measured acoustic parameters of the calls with the Raven Pro 1.6 software (Cornell Lab of Ornithology; https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/) using brightness and contrast = 70 and Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) = 512 (e.g., Nali and Prado 2014a). We followed the same acoustic nomenclature as in Nali and Prado (2014a) and measured the following acoustic parameters for each note: dominant frequency (Hz), minimum frequency (Hz), maximum frequency (Hz), note duration (s), number of pulses per note, pulse rate (N pulses/s), and number of groups of pulses per note. We compared the acoustic parameters of the courtship calls of the digital recorder vs. audios from the camera using Kruskal-Wallis tests to decide if we could combine those two sources for the call description. Also, as courtship calls seem to be a modification of the long notes of the advertisement call in this species (Nali and Prado 2012, 2014a), we compared acoustic parameters from the long note of the advertisement call vs. the courtship call emitted by the same male using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Significance values were assessed under P < 0.05.

RESULTS

On 24 January 2013 at 21:00 h (air temperature = 20 °C, relative air humidity = 77.8 %), we observed and recorded a vocalizing male (SVL = 38.10, voucher = CFBH 35867). Right afterwards, we observed a female nearby (SVL = 36 mm; voucher = CFBH 40566). We collected the pair and placed them in a transparent plastic bag with a small quantity of water from the environment. We held the bag statically but tilted, so that one of the tips was filled with water.

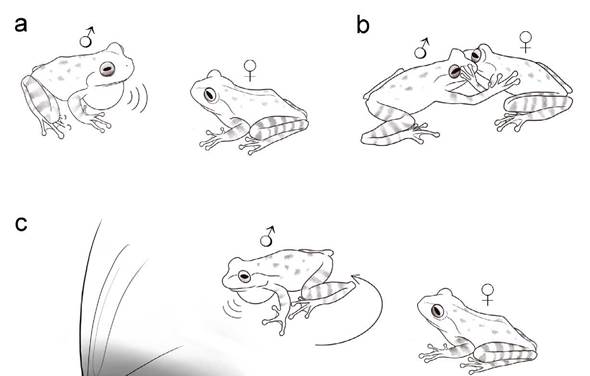

The courtship behaviors displayed included a female touch at the side of the male's head while he was emitting a courtship call right in front of her, and a second touch apparently on the male's leg when he suddenly moved up inside the plastic bag. The male then positioned himself again in front of the female, emitted a courtship call (Fig. 1a) and slapped the female on her side while the female touched the male by rapidly moving her arms up and down (Fig. 1b). After that, the male emitted another courtship call and walked to the plastic bag tip with water, guiding the female towards it (Fig. 1c). Approximately 15 s later, the female jumped to the same site. A video of this sequence of events was deposited in FIGSHARE under the link https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14696109. For the next three minutes, the male kept moving around, occasionally emitting courtship calls towards the female. The female displayed hand movements towards the border of the plastic bag while submerged in the water, as if she were adjusting and inspecting the oviposition site, and not signaling towards the male. On a few occasions, the male emitted advertisement calls, composed by long notes followed by a sequence of short notes (Nali and Prado 2014a). After approximately 10 min of observation, am-plexus did not occur and we ceased observation. At 22:50 h, we continued our fieldwork and when we returned, at 23:40 h, the female had laid eggs in the water accumulated in the bag tip. The clutch contained 142 eggs that were brownish at the animal pole and cream at the vegetative pole. Mean egg diameter was 1.64 mm ± 0.02 mm (range = 1.60 - 1.68 mm, N = 20), each surrounded by a gelatinous capsule with a mean diameter of 4.36 mm ± 0.26 (range = 3.9 - 4.78, N = 11).

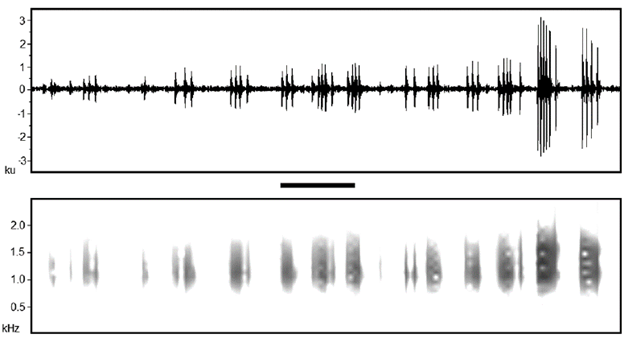

We registered three courtship calls with the digital recorder and five courtship calls from the WAV files extracted from the videos. All call parameters were statistically similar between these two groups (P > 0.05), so we combined the eight notes to describe the courtship call of the species. The courtship call of B. ibitiguara is composed of a long note with pulses distributed in groups (Fig. 2). Values of the acoustic parameters of the courtship call are shown in Table 1. The courtship call resembles the long notes of the advertisement call. However, when comparing the acoustic parameters of the long notes of the advertisement call vs. notes of the courtship calls, we found that the courtship calls had fewer pulses per note, lower dominant frequency, higher minimum frequency and lower maximum frequency, i.e., narrower call frequency bandwidth (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

We uncovered that the courtship behavior of B. ibitiguara is even more complex than previously described (Nali and Prado 2012). In addition to male slaps on the side of the female and nest inspection by the female already recorded (Nali and Prado 2012), we observed female touches on the male (see video above; Fig. 1). A female slap on the male had also been observed during a fieldwork in 2015, but we were not able to record it (R. C. Nali, pers. obs.). Thus, the video recording described here confirmed male and female tactile stimuli during the courtship in this species. Female touches are considered important reproductive stimuli and have been described for Bokermannohyla alvarengai (Bokermann, 1956), B. nanuzae (Bokermann and Sazima, 1973), and species of the genus Aplastodiscus, which belongs to the same tribe (Cophomantini; Zina and Haddad 2007, Lima et al. 2014, Centeno et al. 2015, Lyra et al. 2020, Faivovich et al. 2021). Probably male and female touches during the courtship in B. ibitiguara represent not only tactile stimuli, but also chemical communication arising from specialized lateral and mental glands (Brunetti et al. 2015). Mental glands are known for B. ibitiguara (Faivovich et al. 2009, Brunetti et al. 2015) and both mental and lateral glands occur in several related species (Brunetti et al. 2015). Specific studies are needed to confirm chemical communication in this group of frogs.

Figure 1 Some of the courtship behaviors displayed by a pair of Bokermannohyla ibitiguara inside a plastic bag, in Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil. a The male emits one courtship call in front of the female, b the male slaps on the side of the female's body, while she touches the male by rapidly moving her arms up and down, c the male turns around and emits one courtship call right before walking toward the plastic bag tip with water, guiding the female. See text for video link.

Table 1 Acoustic parameters of the courtship call of the tree frog Bokermannohyla ibitiguara, recorded from one pair inside a plastic bag, and long notes of the advertisement call of the same male prior to courtship and outside the bag, in the Serra da Canastra National Park, Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil. The results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (minimum - maximum). Kruskal-Wallis tests results for each comparison of acoustic parameters between courtship calls and long notes of the advertisement calls are shown.

The typical advertisement call of B. ibitiguara consists of six long notes followed by a sequence of short notes (Nali and Prado 2014a). Playback experiments confirmed that these short notes are aggressive signals directed to males and that long notes would play a role in female attraction (Nali and Prado 2014a). The long notes of the advertisement call are audibly similar to the notes of the courtship call, so we provide further evidence that long notes are related to female attraction in this species. However, long notes of the advertisement call and courtship calls differed in some acoustic parameters, including the dominant frequency (Table 1), a different pattern observed in two congeneric species. In B. luctuosa (Pombal and Haddad, 1993), courtship and advertisement calls show similar dominant frequencies (Zornosa-Torres and Toledo 2019). In B. nanuzae, the spectral properties of both calls are also similar, including the dominant frequency (Lima et al. 2014). This pattern was also found in other species of the tribe Cophomantini, such as Aplastodiscus arildae (Cruz and Peixoto, 1987), Boana rosenbergi (Boulenger, 1898), and Boana atlantica (Caramaschi and Velosa, 1996) (Höbel 2000, Zina and Haddad 2006, Camurugi and Juncá 2013).

From previous studies mentioned above, one could ask: why would dominant frequencies differ between both call types in this species? The dominant frequency of the advertisement call of B. ibitiguara is a static property that is important for individual discrimination (Turin et al. 2018). In addition, larger males emit calls with lower dominant frequencies (Nali and Prado 2014a, Turin et al. 2018), potentially signaling better competitive ability for males and females (Nali and Prado 2014a). The fighting call of the species has a lower dominant frequency and males significantly lower the dominant frequency of the short notes of the advertisement call in aggressive contexts (aggressive call; Nali and Prado 2014a, b). Nali and Prado (2014a) uncovered that, when exposed to playbacks, males changed some parameters of the short notes of the advertisement call, which included lowering their dominant frequency. In this study, we confirm this ability to modify parameters of the long notes as well, i.e., the same male lowered the dominant frequency of the long notes of the advertisement call when the female approached, described here as courtship call. Thus, we hypothesize that males, when lowering the dominant frequency, could maximize the chances of amplexus by advertising a better competitive ability to females, which reinforces the role of sexual selection in shaping call variation in this species (Nali and Prado 2014a, this study).

Figure 2 Oscillogram (above) and spectrogram (below) of a courtship call of Bokermannohyla ibitiguara, recorded in the field immediately after the pair was collected and kept within a plastic bag in Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil. Observe one note of the courtship call composed by groups of pulses. Air temperature = 20°C, brightness and contrast = 70, FFT = 512. Scale bar = 0.1 s. Male snout-vent length = 38.10 mm; voucher specimen = CFBH 35867.

Courtship calls in frogs are often described as a version of the advertisement call with lower intensity (Felton et al. 2006, Wells 2007, de Sá et al. 2016, Köhler et al. 2017). Although we did not measure call intensity, this is audibly the case for the species (Nali and Prado 2012) and is also suggested by the narrower call frequency bandwidth (this study). Together with the fewer pulses compared to the advertisement call, this could be a strategy to avoid competitors, predators and energy expenditure in a situation in which one female is already engaged in courtship (Felton et al. 2006, Wells 2007).

Animal behavior may be strongly influenced by the presence of the observer (Martin and Bateson 2007) and specifically for frogs recommendations include avoiding pointing the flashlight directly onto the animals and using red lights (e.g., Miranda et al. 2008, Nali and Prado 2012). Although we encourage field observations applying these procedures, we suggest that rare behaviors should be reported even in artificial conditions, given that some of them are difficult to observe in natural conditions (Berneck et al. 2017, Pogoda 2019). The courtship call we describe here is a clear example, being only the third courtship call described for the whole genus. Our results not only expand our knowledge on the biology of the species, but also sheds light on mating behavior and the role of sexual selection in shaping call variation in frogs.