Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile no.7 Bogotá Jan./dec. 2006

Adriana González Moncada1

1 Holds a doctoral degree in Linguistics (TESOL) from State University of New York at Stony Brook. She is a teacher educator and researcher interested in foreign language teacher education and professional development issues. She is currently the Director of the School of Languages at the Universidad de Antioquia.

agonzal@quimbaya.udea.edu.co

This paper reports on the findings of a case study carried out at Universidad de Antioquia as well as explores training on materials use in our teacher preparation program and its effectiveness in the practicum. The data analyzed suggest that, although teacher educators having new approaches to train future teachers in materials use, they still need to revise the way they include this component in teacher preparation curricula. Training in the use of materials should include their use in settings with limited resources as well as those with greater possibilities in technical and non-technical materials. Lastly, the author raises awareness about the need to include materials use as an issue in local and national EFL teacher education agendas.

Key words: Materials use, training, teacher education, practicum

Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio de caso llevado a cabo en la Universidad de Antioquia en el que se exploró la capacitación que damos a nuestros estudiantes de pregrado en el uso de materiales y su efectividad en la Práctica Docente. El análisis de los datos sugiere que a pesar del avance en la forma como los formadores de docentes tratamos el uso de los materiales, se hace necesaria una revisión de la forma cómo los estudiantes son expuestos a este uso. La formación en el uso de los materiales debe incluir contextos escolares en los que haya recursos limitados y aquellos donde haya mayores posibilidades en materiales técnicos y no técnicos. Finalmente, la autora llama la atención sobre la necesidad de incluir el uso de los materiales como un punto en las agendas de formación de docentes a nivel local y nacional.

Palabras claves: Uso de materiales, entrenamiento, formación docente, práctica docente

INTRODUCTION

This paper reports on the findings of a case study carried out at the Universidad de Antioquia as well as explores the way our future foreign language teachers are trained in the use of teaching materials. This reflection is based on my role as a teacher educator, and it presents an analysis that includes both a retrospective and current assessment of how our institution has approached materials training.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Materials are an essential component in teaching. As a starting point, I present some definitions found in literature. Ramírez (2004, p. 2) defines materials as “anything used by teachers or learners to facilitate the learning of a language.” Tomlinson (1998, p. 2) includes the following in the list of possible materials: “cassettes, videos, CD-Roms, DVDs, dictionaries, grammar books, readers, workbooks, photocopied exercises, all kinds of realia, lectures and talks by guest speakers, Internet sources, and so on.” Brinton (1991) defines materials, “the media” as she calls them, into non-technical and technical media. In the first category she proposes the following items: “blackboard/whiteboard, magnetboards/flannelboards/pegboards, flashcards, index cards, wall charts, posters, maps, scrolls, board games, mounted pictures, photos, cartoons, line drawings, objects/ realia, pamphlets/brochures/leaflets/flyers, equipment operation manuals, puppets, newspapers/ magazines.” She says that these items have many advantages in places where technical resources are scarce. They are also cheap and user-friendly. The technical media category is composed of the following: “audiotapes/audio-recorders/players, records/record players, CD’s/CD players, radio/television, telephones/teletrainers, films/film projectors, computer software/hardware, overhead transparencies/overhead projectors, language lab/multimedia lab, opaque projectors, slides, filmstrips/slide and filmstrip projectors.” Contrary to those from the first group, the latter are expensive and less user-friendly. McDonough and Shaw (1993, p. 9) list the following materials as needed in the English classroom: “books and paper, audio-visual material (hardware and software for cassette and video), laboratories, computers, reprographic facilities and so on.” They also argue: “the design and choice of teaching materials will be particularly affected by the availability of resources as well as the capacity to teach effectively across a range of language skills.” For this paper, materials will refer to textbooks, computer software and visual aids as well as video and audiotape equipment. I decided to focus on their use for two reasons: one, these materials are available in all the teacher preparation programs in Colombia; and two, they are cited by EFL teachers as the basic devices to teach an effective English lesson.

Teachers and students recognize the importance of using materials, since the teaching process is made easier and materials may be used to explain, exemplify or practice the content presented to students. Materials can represent a source of motivation for students when these materials change the dynamics of the class routines through the possibility of manipulating objects, accessing audiovisual material or promoting interaction with others. Materials, if chosen adequately, can promote the integration of language skills by addressing language and content in a holistic way (Hinkel, 2006). In terms of learning styles (Reid, 1995) and intelligences (Gardner, 1993; Armstrong, 1994), materials can also help the teacher address the individual differences of students. Additionally, the use of materials helps teachers motivate students by “bringing a slice of real life into the classroom and presenting language in its more complete communicative situation” (Brinton, 1991).

Presently, the rapid growth of technology offers many more options than those proposed by Allwright in the 1980s or by Brinton, McDonough and Shaw in the 1990s. Supyan (2004), Tomlinson (2005), Harmer (2001), Kitao and Kitao (1995), among others, report on the benefits of various options provided by CALL, especially concerning the possibility of responding to students’ needs in a more individualized way. As a part of the new materials available now for language teaching, we can find an overwhelming amount of papers reporting on the advantages and disadvantages of the use of the new technologies in language teaching.

Materials are considered a key element in language teaching and may have the same status in language instruction as students, teachers, teaching methods and evaluation (Kitao & Kitao, 1997). These five elements are interrelated. Thus any change introduced to any of these elements will affect the others. Defining a closer relationship between materials and students’ motivation, Peacock (1998) found that materials considered “enjoyable” and “useful” increased the on-task behavior in English classes. Consequently, students became more involved in the learning tasks.

McDonough and Shaw (1993) state that course planning, syllabus design, the appropriateness of methods as well as the selection of materials and resources, will be affected by the following factors: the role of English in the country, the role of English in schools, teachers, management and administration, available resources, support personnel, number of pupils, available time, physical environment, socio-cultural environment, types of tests used as well as procedures for monitoring and evaluating the program itself. Arias (1994) included materials as one of the factors in the dynamics of teachers’ professional development, since materials may exert some influence on the teachers’ work with colleagues. She invites teacher educators to consider materials to be a powerful variable that may affect learning and teaching, since they are particular to the different settings.

Although the literature reviewed stresses the importance of materials, there is no evidence of studies carried out in Colombia that critically review how EFL teacher education programs address training on materials use in the curricula. This paper intends to provide a description of a particular teacher education program to enable teacher educators to reflect critically on the training given to undergraduates in our local and national contexts.

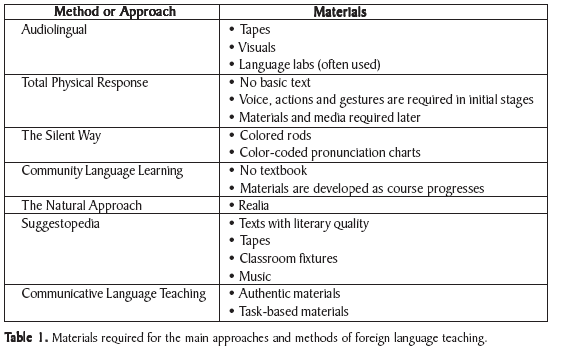

Some ELT methodologies have based their implementation on the use of certain kinds of materials. Without access to those resources, teachers may have serious difficulties with carrying out their teaching under the principles of the given methodology. Brown (1994, pp. 70-71) summarizes the materials required for the main approaches and methods of foreign language teaching as shown in Table 1.

Subsequent approaches to foreign language teaching such as Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT) (Nunan, 1993) or the Natural Approach (Krashen & Terrell, 1983) claim the use of authentic texts, oral and written, as a requirement in their implementation. Although methods may require a specific set of materials that may be indispensable for their effectiveness, textbooks became an alternative because they were apparently eclectic alternatives to save time and money. Pictures and graphic materials presented in textbooks may be more efficient than teachers’ descriptions, and can represent all kinds of objects that may be hard to take to the classroom. The critical evaluation of textbook use is nowadays a must (Seldon, 1988) as teachers are the main participants in their process of reflective teaching.

After decades of trying to find a method that works in different settings and significant analyses of the failures of some methods, language teachers and teacher educators understood the need to become eclectic. Language teachers are to make informed choices based on what works for them in their particular setting (Brown, 1994). Newer approaches in teacher education reveal that we have moved away from the conception of the existence of one single “method” to teach languages. We recognize the value of post-method pedagogies in which teachers are reflective practitioners that use what they find effective for their classes (Kumaravadivelu, 2003; 2005; 2006).

The framework proposed by Kumaravadivelu includes three operating principles that apply to the needs, wants and situations faced in diverse settings, which of course include materials, and these are particularity, practicality and possibility. The author defines these principles as:

Particularity seeks to facilitate the advancement of a context-sensitive, location specific pedagogy that is based on a true understanding of a local linguistic, social, cultural, and political particularities. Practicality seeks to rupture the reified role relationship between theorizers and practitioners by enabling and encouraging teachers to theorize from their practice and to practice what they theorize. Possibility seeks to tap the sociopolitical consciousness that students bring with them to the classroom so that it can also function as a catalyst for identity formation and social transformation (Kumaravadivelu, 2006, p. 69).

As a logical consequence of these principles, teacher educators must study more closely how they can help future teachers in using materials in the EFL classroom. The particularity principle is important in our materials training as teacher educators need to provide student teachers with alternatives to their particular contexts, since they may be EFL teachers in rural settings, underprivileged neighborhoods in urban areas or private schools with various types of teaching materials. In the search for practicality, teacher educators need to help students find a situated, eclectic, personal approach to using materials in their teaching. This may allow them to reflect on their experience and write about new ways to teach with and without materials or to look for alternative ways to use traditional materials. The possibility principle may have an application in the awareness training possibility of changing the paradigm of EFL teachers from mere materials consumers in ESL settings to teachers capable of creating effective teaching conditions regardless of the availability of certain teaching materials.

Context of the Study

As an attempt to help future teachers become better qualified for teaching, undergraduate programs give a very special role to training in materials use. Teacher education programs in Colombia include this training as part of the content of the course “Methods of Foreign Language Teaching”. However, in a quick review of the twenty-four undergraduate programs in Foreign Language Teaching available in Colombia, I found that only two universities list on their web pages courses that deal explicitly with materials.1 The courses are “Foreign Language Pedagogy and Materials Production” at the Universidad del Cauca2 and “Course and Materials Design” at the Universidad de Antioquia.

The program at the Universidad de Antioquia has increased the importance given to materials in the foreign language teacher preparation program. Since 1996, materials are included as a component of the curriculum. As a faculty member, I have been in contact with the following course programs:

• 1996-1998: Medios Auxiliares de la Enseñanza y Evaluación de L2/L3 (Materials and Assessment in L2/L3). This was a mandatory course taught twice a week using computers at least once. Two samples of the programs implemented for this course are presented in Appendix 1. Regarding the materials component, the main scope of the course was to train students in the use of computers, as it was a growing need for EFL teachers. Students learned to type their own papers using “Word” and to use electronic mail (something quite new in Colombia at the time).

• 1998-1999: Medios Auxiliares de la Enseñanza y Evaluación. In 1998, I became a faculty member at the Universidad de Antioquia. After analyzing the previous program and talking to student teachers, I came up with a new version of the program (see Appendix 2). The materials component was taught in the first part of the course, devoting less time to assessment.

• 1999-2000: Medios Auxiliares de la Enseñanza y Evaluación. After having reviewed the students’ suggestions and comments from the previous semester, I introduced some changes to the program for both semesters in 1999. One, the same topics were organized according to the students’ ranking. Based on their needs in the practicum, the students proposed, first, having the assessment component and then, the materials component. Two, I decided to focus more on the use of technical materials as my students insisted on their need to be familiarized with computers. Most of them did not have a computer at home; therefore, using them in class was one of their main motivations. And three, the use of the Internet, e-mail and multimedia software became the topics on which I spent more time.

In the first semester 2000, I stopped teaching the course. From then and throughout 2002, the course was taught by another faculty member who did not introduce any changes. In 2002, a deep revision of the curriculum motivated the program curriculum committee to separate the topics of materials from assessment. Materials became part of a new elective course called “Syllabus Design and Materials Development” (see Appendix 3). This course was designed as a possible way to help students overcome some of the problems they faced in the design of a research project for the practicum and to use materials better in their classes. Assessment was reorganized as a new core course. Its main objective was to provide students with more elements to understand and apply testing and alternative assessment in their classes.

The ongoing evaluation practice in the curriculum has made professors adjust the course to the students’ needs. The presentation of materials as part of the elective course was seen by the students as an academic asset from 2002-2004. In 2004, some variations were introduced to the program. The unit proposed for the materials component in the 2004 version is presented in Appendix 4.

In a review of the archives, the students’ evaluations for the academic years 2000-2001 show the benefits of this course to be an important element in their practicum. They acknowledged the importance of gaining awareness about the use of materials as well as the principles for adapting them. Yet, there is no documented evidence of the real impact the course may have had on their teaching, as there were no reports from practicum supervisors or cooperating teachers regarding the students’ use of materials.

METHODOLOGY

As a teacher and teacher educator, I have always been challenged by the students’ and teachers’ ongoing complaints about not having enough materials to teach with and needing more training on how to use and design them. Based on this need, I decided to explore training on materials use at the Universidad de Antioquia. The research questions that led the study were 1) How effective is the training on materials use for our students’ performance in the practicum? and 2) What elements should teacher educators include to improve that training?

I decided to do a case study since it allowed me to explore in some detail the particular setting of the Universidad de Antioquia with a limited number of participants in some detail (Tellis, 1997; Yin, 1994).

Participants

Participants were student teachers from the undergraduate program, practicum supervisors and EFL teachers. The students from a “Materials and Course Design” class were invited to participate, but only five of them expressed willingness to do so. These five students were doing their practicum in different public schools in Medellín in 2003. EFL teachers were contacted to participate in a larger study on their professional needs. Eighteen public school teachers offered to share their insights. Their interviews on materials were used to contrast and complement the students’ views. Three of the teachers were also cooperating teachers in the foreign language teaching practicum. All of them signed a consent form in which they allowed me to use their testimony and were informed of the research conditions. I used fictitious names in this paper to guarantee confidentiality.

The students informed me of their training regarding materials use. Cooperating teachers informed on the effectiveness of the students’ training and EFL teachers on their needs regarding materials. The three sets of views were intended to improve the efficiency of our undergraduate program regarding materials use.

Data Collection

Data collection included a documentary analysis of versions of the programs of “Materials and Assessment”, “Course Design and Curriculum Development” and “Course and Materials Design.” It also included the course evaluation files, two in-depth interviews (Kvale, 1996) with student teachers and cooperating teachers as well as two focus group sessions with EFL teachers (Debus, 1990)3 .

Data Analysis

The interviews and the focus group sessions were transcribed using standard orthography. Then, I read the texts looking for common patterns and identifying meaningful units. Then, the units were labeled and grouped to construct categories. My epistemological assumptions were interpretive (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Bassey, 1999; Silverman, 1993), as I based my analysis of the training on materials use in our program through a semiotic analysis of the data collected. I constantly compared the categories obtained with the units highlighted in the transcriptions to understand their relationship. I based the analysis on a grounded approach (Freeman, 1998) as I constructed the categories taking into account what the participants reported.

Data were validated through participant triangulation and data triangulation (Freeman, 1998), contrasting the opinions of the student teachers, cooperating teachers and EFL teachers. Three versions of the course program were analyzed.

FINDINGS

The data analyzed reported some contradictory issues regarding the training on materials use in the teacher preparation program at the Universidad de Antioquia. Student teachers seem to believe that they know enough about using materials; however, once they become teachers in real classrooms, they report it as one of their main professional needs. The following ideas are the main ones concerning materials use:

a. Lack of materials: The different teachers’ statements report this as the main issue. Although this may be a reality in Colombia, it is important to treat this limitation separately. Materials do not seem to be sufficient either as part of the resources for the practicum in our university or as part of the resources available at practicum settings as well as in the majority of the public schools in Colombia. Student teachers said repeatedly that they would like to have a resource center on campus where they could borrow different materials to bring to their practicum settings. The resources available at the university are mainly intended to teach in extension programs or to be used in the foreign language training of undergraduates.

Martha states:

“I wish we had more materials to take to the practicum schools. The videos available are too long and difficult to our beginner students in high schools and the themes are more for our interest as university students… The games and flashcards are to be used only on campus in the English program for children and adolescents.”

Eduardo, a student doing his practicum at a public school in a low-income neighborhood, states the problem of the lack of materials at the University as:

“Student teachers have access to very limited material, much of which is too geared for children or too advanced for our real needs, nothing specific for teenagers, our students in the practicum. We have English textbooks, grammar books, dictionaries and some very old and long story books, a lot of theoretical material, but no practical material.”

To solve the problem of lack of resources, student teachers try to make their own material. However, besides being a challenge for students, it may be a problem as practicum settings may not have materials either. All access to materials may depend on the English teacher or the student teacher.

Eduardo also states:

“This involves time, money and effort on our part, with little or no help from the school or the cooperating teachers. In the end, most of this material remains locked in a drawer and hardly ever gets to be used again. Is this worthwhile? Sometimes we get the material, we make it, and then ask the school for scotch tape or minor things to be able to use in the classroom and most of the time schools don’t even provide us with this.”

Every day, EFL teachers face the limitation of access to materials. Budgetary cuts in Colombian education have consequences for the quality of the support provided to schools. The sad reality of almost no resources is contrasted with the ideal school in which teachers have access to many technical and non-technical materials. More recently, the idea of a “Bilingual Classroom”4 , in other words a classroom equipped with computers and software to teach English, seems to be the dream of the majority of schools. The demand for esources may be as strong as the fundamental issues in the profession. From the eighteen EFL teachers interviewed, eleven reported the need for more materials as one of their main professional needs. Some of the teachers’ remarks were the following:

“I’d like smaller classes, a Xerox machine, a TV set, a VHS/DVD player, a tape recorder, and more expertise in English teaching methodology.” (Luisa)

“I’d like to study abroad, to have a language lab in my school and to have the opportunity to attend professional development programs for free.” (Rosa)

“I’d like to count on more teaching resources. In the majority of schools we work with there is nothing to develop my fluency in English and to be able to motivate my students.” (Ana)

“First, having an ideal environment to carry out my job as an English teacher. Second, having access to the appropriate resources to teach, like language labs… Third, having total freedom to create, change, improve… a space without administrative restrictions.” (Darío)

“I’d like to have a VHS/DVD player and a TV set for each classroom…and one classroom used exclusively in English class where I can have the materials. Students will come to this classroom. I won’t have to go to their classrooms.” (Dora)

“I’d like to have a library with a considerable number of books and videos in English, we may think about some classics. If students have access to the Internet, they may also learn about Shakespeare or Joyce.” (Marcos)

b. Limited access to existing resources: As a consequence of the budgetary constraints, also identified by Brinton (1991) as a teachers’ difficulty in the use of materials, resources have to be shared by a great number of teachers, and not only by English teachers. A tape/CD player may be a common element in foreign language classrooms in developed countries. Nevertheless, many EFL teachers may experience difficulties accessing this item. González (2000) cites the case of an English teacher and her daily struggle to use some material in her classes. The teacher said:

“In my school, we have a single tape recorder for the whole school. Sometimes I find myself reserving the tape recorder two weeks in advance because the music teacher, the French teacher and the physical education teacher would also like to use it at the same time I had planned to do so.”

There are also some additional factors that may affect the use of resources such as the lack of electricity or the lack of a socket, plug or switch to operate any kind of electronic device. These factors may be a challenge that interferes with the development of the planned lesson, as it may not be anticipated.

Some schools may have the resources suggested in the literature, but it is not possible for teachers to use them. They may not even know the existence of those teaching aids. Some teachers have repeatedly reported in informal conversations and professional meetings that their schools have computer labs5 that are more a “sanctuary” than a learning resource for students. Those rooms are locked and equipment is hardly used. They are open when district supervisors visit the institution. Elkin, a student teacher, reports on his experience in one public school:

“In my school there is a computer room. There are five computers and I have forty-five students. One day I wanted to take them to the “lab”, but I found out that no one knew where the key was. Apparently the principal had it. One week later, my cooperating teacher found the key. We turned the computers on and discovered that there was no Internet connection. My brilliant idea was just a dream.”

Unless the schools have someone in charge of administering, lending, repairing and keeping the resources in a place accessible to teachers, those aids become part of the school’s decoration.

c. Lack of awareness of their limitations in materials use: Although syllabi have changed in the place granted to materials in teacher preparation at the Universidad de Antioquia, most students tend to consider their training as something not really necessary when it has to do with non-technical material. In a few cases, student teachers acknowledge their limitations in the choice, use, adaptation or design of materials. Even in their teaching experience, they believe they adequately employ teaching aids. In my reflection notes6 , from the materials and assessment course I taught, I highlight:

“At the end of the course, students in their evaluations reported having more interest in learning about the assessment component than about materials.”

(Course evaluation Semester 1998-I)

“Negotiating the course content with the students showed me once again that the materials component was considered less important for them than the assessment component. When I invited them to support their ideas, students reported having had “enough training” in the use of non-technical materials from the Methods I and II courses taken previously. Their main interest was evident as we started using the computers.”

(Course evaluation Semester 1999-I)

My reflections from that time seem to be still relevant. Erica, a student teacher, commented on her personal training on materials:

“In the Methods courses we studied about skills integration and communicative language teaching, as well as the materials we should use, but when I teach my English class sometimes I feel confused. I am not quite sure how to adapt a good reading from the Internet or how to design some games to practice certain language structures. The Course and Materials Design course was very good, but I need more time to share ideas with classmates and the teacher.”

Contrary to the positive view of some student teachers, some cooperating teachers have a quite negative outlook. The three cooperating teachers agreed on the following issues as problematic for some student teachers in their practicum settings:

1. Overusing “work sheets” to practice grammar structures;

2. Insufficiently and ineffectively using the board;

3. Making material (flashcards, mounted pictures) that are not quite useful;

4. Choosing inappropriate material for the students’ cognitive and linguistic level;

5. Having difficulties in the design of effective activities using computers.

They also said that students do not seem to be aware of these limitations in their self-assessment and have diverse opinions on the need to have longer and deeper training in materials use.

d. Exposure to unrealistic settings: Undergraduates in our program are trained in the use of materials in the Methods I and II courses and in the “Course and Materials Design” course. The first two are mainly theoretical courses that provide students with some principles to face their future teaching. The reflections held in these classes may be based on unreal classrooms portrayed in literature or in retrospective analyses of their own learning conditions. The third course, scheduled at the same level of the practicum, contains only one unit on materials use. This could take only about 20 hours of the instruction time (See Appendix 4). In this class, students carry out a small scale project in a resource center at an institution, mainly private language centers in Medellín. There the students become familiar with the materials available and the curriculum as well as the students’ needs to be able to design a course or a unit. Although this course shows some improvement in the quality of the training in materials use, students may not experience teaching in these institutions because the practicum handbook at the university stipulates that the settings for the EFL practicum must be public schools.

Darío, a teacher in a public school that has a “Bilingual Classroom”, made the following suggestion to improve teacher education programs regarding materials use:“You should expose students to the use of multimedia software and the adaptation of Internet pages to our classrooms. They could go to the schools and help us because we have some problems using and adapting technology.”

Rosa, a teacher who works in a very poor neighborhood, said this about the training required by student teachers:

“As a student, one needs to learn to work with nothing. I cannot ask my students to buy a textbook, a dictionary, or to get some money to pay for copies. I just have the board and chalk. It’s very hard to be creative under these circumstances. I wish student teachers could visit my school and face the reality of displaced people who have nothing. I’m sure the university does not expose them to that kind of reality.”

There is another reality that the Universidad de Antioquia may not be taking into consideration, namely, the private schools and language centers that possess lots of technical and non-technical materials. Students need to be exposed to the use of new technologies and to the multiple applications of CALL. They ask for more time in the curriculum to use the language lab and express the need to acquire more software in order to be prepared for the job market in private institutions.

Due to the limitation of resources at the Universidad de Antioquia, our students are trained to use some “standard” resources such as the Internet, videos, tapes, flashcards and games. The use of specialized software for language learning or the immense possibilities of virtual learning is not our program’s strength.

I would mention one last issue regarding the complexity of finding an effective approach to materials use in teacher education. In the search for this, teacher educators may easily forget simple issues such as the use of the board, the design of a handout or the construction of cheap materials because technology seems to impose a more striking demand. We cannot forget that the diversity of EFL settings in Colombia ranges from classrooms with no materials to classrooms with the latest technology in language learning. Both settings are real and deserve the analysis of teacher educators.

CONCLUSIONS

This case study is an introductory exploration to the training on materials use in teacher preparation programs in Colombia. It has some limitations that may have contributed to the conclusions drawn. On the one hand, as mentioned previously, access to the programs regarding materials use in Colombian universities was quite limited. It may be possible that more institutions address this topic explicitly as part of their teacher preparation program. On the other hand, the analysis of the course content dealing with materials at the Universidad de Antioquia from the point of view of a teacher educator was restricted to the retrospective analysis of the author from 1996 to 1998. It was not possible to compare my own notes with the students’ course evaluations because they were not available in the archives. More student teachers and practicum supervisors as well as teachers need to be included in a broader study. Additionally, more research on the implications of the changes implemented in the curricula is needed to comprehend better the impact of the training on the students’ performance in the practicum. Further research needs to be done on the professional needs of EFL teachers regarding materials use, including technical and non-technical materials. The documentary analysis demonstrated that our treatment of materials use may require some deeper reflection as a part of local and national teacher education agendas. This may not be only an aspect to be improved in our university. It may apply to other teacher education programs in Colombia and in other EFL settings.

As conclusions, I highlight the following issues:

EFL Teachers see materials as a very important component in effective teaching. They tend to associate effective teaching with the availability of different kinds of materials, mainly technical.

Student teachers require longer and deeper training in the use of technical and non-technical materials. They must be acquainted with different possibilities to make adequate choices in their classroom settings.

Teacher educators need to expose students to real school contexts in which students face the limitations in the use of materials experienced in regular EFL classrooms. Additionally, they need to train future teachers in the use of applications of multimedia in teaching and learning foreign languages as private schools and language centers include the use of these materials as strengths in their EFL programs.

I would stress the following aspects as tasks to be considered by teacher educators in local and national agendas regarding materials use:

1. Present “materials” as an independent component in teacher education in the form of a course. This may include aspects such as the reflective use of technical and non-technical materials, the adaptation and design of tasks as well as a more intensive and critical exposure to CALL. This course should be complementary to the practicum so that students have the opportunity to connect effectively and authentically the theory with the practice.

2. Envision scheduling short internships in schools that have no resources as well as in ones with lots of resources so that students may be acquainted with both realities.

3. Include materials use as an issue to be studied by teacher educators in the professional agendas. A comprehensive analysis of the training used in diverse settings may contribute to theorizing on better ways to prepare EFL teachers. The challenges faced by our teachers may be the same in many developing countries.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply thankful to the anonymous reviewers whose suggestions improved this paper enormously. I am also thankful to my colleague, Clara Arias Toro, for her insights.

1 The other twenty-two programs reviewed include some elective courses. It was not possible to identify the names and content of these courses; therefore, it might be possible that some of them address the use of materials.

2 I tried to obtain the course program to analyze its content for this paper. Unfortunately, it was not possible.

3 The focus group transcriptions belong to the study “Professional Needs of EFL Teachers from Public and Private Schools in the Metropolitan Area of Medellín” sponsored by CODI, Universidad de Antioquia.

4 Some schools have been provided with these classrooms. They may be a set of computers that have access to the “English Discoveries” Software. There is no evidence of any local study regarding the benefits of counting on this resource.

5 Some schools have been provided with these classrooms. They may be a set of computers that have access to the “English Discoveries” Software. There is no evidence of any local study regarding the benefits of counting on this resource.

6 I kept a teaching diary for the courses from 1998 through 2000 as a way to reflect on my new job as a teacher educator in a public university.

REFERENCES

Allwright, R. L. (1981). What do we want teaching materials for? ELT Journal, 36, 15-18. [ Links ]

Arias, C. (1994). Teacher development: Meeting the challenge of changing worlds´ keynote speech at the 29th ASOCOPI congress. Medellín, Colombia. [ Links ]

Armstrong, T. (1994). Multiple intelligences in the classroom. Alexandria. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. [ Links ]

Bassey, M. (1999). Case study research in educational settings. London: Open University. [ Links ]

Brinton, D. (1991). The use of media in language teaching. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 454- 472). Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Brown, D. (1994). Teaching by principles. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [ Links ]

Debus, M. (1990). Handbook for excellence in focus group research. Academy for educational development: Washington, DC. [ Links ]

Ellis, R. (1997). The empirical evaluation of language teaching materials. ELT Journal, 51, 36-42. [ Links ]

Freeman, D. (1998). Doing teacher research: From inquiry to understanding. Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

[ Links ]

González, A. (2000). The new millennium: More challenges for EFL teachers and teacher educators. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2, 5-14. [ Links ]

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching. (3rd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Hinkel, E. (2006). Current perspectives on teaching the four skills. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 109- 132. [ Links ]

Kitao, K., & Kitao, K. (1995). English teaching: Theory, research and practice. Tokyo: Eichosha. [ Links ]

Kitao, K., & Kitao, K. (1997). Selecting and developing teaching/learning materials. The Internet TESL Journal, IV(4). [ Links ]

Krashen, S., & Terrell, T. (1983). The natural approach. Hayward, CA: Alemany Press. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2005). (Re)Visioning language teacher education. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Language Teacher Education. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota June 2-4. [ Links ]

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL methods: Changing tracks, challenging trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59- 81. [ Links ]

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

McDonough, J., & Shaw, C. (1993). Materials and methods in ELT. Cambridge: Blackwell. [ Links ]

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Nunan, D. (1993). Communicative tasks and the language curriculum. In S. Silberstein (Ed), State of the art TESOL essays (pp. 52- 68). Alexandria: Virginia. [ Links ]

Peacock, M. (1998). Usefulness and enjoyableness of teaching materials as predictors of on-task behavior. The Internet TESL Journal, 3(2). [ Links ]

Ramírez, S. M. (2004). English teachers as materials developers. Revista Electrónica Actualidades Educativas en Investigación, 4(2), 1- 17. [ Links ]

Reid, J. (Ed.). (1995). Learning styles in the ESL/EFL classroom. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. [ Links ]

Rossner, R., & Bolitho, R. (Eds.). (1990). Currents in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Seldon, L. (1988). Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials. ELT Journal, 42(4), 237- 246. [ Links ]

Silverman, D. (1993). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Supyan, H. (2004). Web-based language learning materials: A challenge. Internet Journal of E-Learning & Teaching, 1(1), 31- 42. Retrieved March 2006, from http://www.eltrec.ukm.my/ijellt/archive.asp [ Links ]

Tomlinson, B. (2005). The future of ELT materials in Asia. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2(2), 5- 13. Retrieved March 2006, from http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v2n22005/tomlinson.pdf [ Links ]

Tomlinson, B. (Ed.). (1998). Materials development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The qualitative report, 3(2). Retrieved May 2005, from http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR3-2/tellis1.html [ Links ]

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]