Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile no.10 Bogotá July/Dec. 2008

Unveiling Students' Understanding of Autonomy: Puzzling Out a Path to Learning Beyond the EFL Classroom*

Descubriendo cómo comprenden los estudiantes el concepto de autonomía: descifrando un camino de aprendizaje más allá del aula de clase de inglés

J. Aleida Ariza Ariza**

Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC)

** E-mail: aleariza71@yahoo.es

Address: Avenida Central Norte, Tunja, Boyacá. Cra 16 No 36-30 Apto 102 Balcones de la Calleja

This article was received on January 30, 2008, and accepted on August 12, 2008.

This paper aims at reporting a research project on students' understandings of autonomy evidenced in their learning experiences while in the EFL classroom and outside of it in a Colombian public university. This research study is conceived as a response to the new paradigm we are exposed to in our social and educational settings in which decision making becomes a key feature of individuals. Data were gathered through field notes, video recordings, a questionnaire, interviews, students' logs and audio-recorded plenary sessions. The results of the study indicated that students conceived autonomy as an opportunity to find a key to learning beyond the classroom. When walking on this path, students faced a dilemma between detachment and teacher dependence; they showed independence in decision making taking advantage of learning opportunities beyond the classroom and engaging in reflection. They also constructed knowledge through experience and carried out learning self-evaluation processes.

Key words: Autonomy, learning experiences, learning beyond the EFL classroom, self-evaluation

Este artículo reporta un proyecto de investigación sobre las concepciones de autonomía de estudiantes evidenciadas en experiencias de aprendizaje de inglés dentro y fuera del aula de clase en una universidad pública colombiana. Este estudio de investigación responde al nuevo paradigma al que estamos expuestos en nuestro entorno social y educativo en el que la toma de decisiones es un elemento primordial para los individuos. Los datos se recolectaron mediante notas de campo, video-grabaciones y bitácoras de los estudiantes. Los resultados del estudio indican que los estudiantes conciben la autonomía como una oportunidad para su aprendizaje más allá del aula de clase. A lo largo de este camino, los estudiantes enfrentaron un dilema entre distanciamiento y dependencia del profesor y mostraron independencia al tomar decisiones utilizando oportunidades de aprendizaje fuera del aula de clase y reflexionar. Asimismo construyeron conocimiento a través de su experiencia y llevaron a cabo procesos de auto-evaluación.

Palabras clave: Autonomía, experiencias de aprendizaje, aprendizaje fuera del aula de clase, autoevaluación

Introduction

This article attempts to report the results of a descriptive research project focusing on students' understandings of autonomous learning and the way these were evidenced in multiple learning experiences both in and outside the classroom in a Basic English course of the undergraduate program in Philology and Languages at a public university in Colombia. Thus, the research question that guides this study is this: What do EFL undergraduate students' learning experiences contribute to our understanding of learner autonomy in the Colombian university context?

The problematic area of the current study was identified through my teaching experiences in different places in which I have shared learning spaces with different types of learners. A recurrent situation in EFL classrooms is the high level of dependence on the teacher that most students display. We, as learners, have been exposed to learning environments where the ones who are entrusted with making most of the decisions are teachers. Thus, students go through the learning process performing a passive role which does not allow them to be part of richer classroom dynamics.

This philosophy of education, in which students are considered merely recipients of knowledge, has been questioned for many years, but its discussion nowadays is at the core of our educational system with the implementation of the credit policy in most of the universities in Colombia. This policy was conceived as a tool for boosting students' independent work, so that they may become more active and committed to their learning process. The credit system implies that for every class hour students attend, they are expected to work two hours independently. Considering credits as the basis of our curricula implies understanding what a credit is and what independent work implies. Under this vision teachers are encouraged to design syllabi considering students' autonomous practices as a crucial element in the development of courses. Bearing this idea in mind, one sees that clarity in concepts such as autonomy and independent work becomes a must.

In the coming sections of this article I will provide a brief discussion of some basic concepts in relation to autonomy, autonomous learning experiences and autonomous learners' characteristics, information about the context and participants of the project, and the research design. In the same fashion, the findings will be presented along with their pedagogical implications and conclusions.

Key Concepts

Autonomy and Autonomous Learning

Society changes all the time and education should accept the challenges that the ever changing society brings with it. Learner independence has become a key issue in today's world.

Nowadays, one of the main aspects in our educational environment is the individual's development. Each learner has a potential and a series of abilities which enables her/him to take an active role in her/ his learning. Our goal, as educators, is to raise our students' awareness about their learning capacities, their responsibility in the learning process, and the importance of taking control over the process in order to be able to cope with the new challenges society presents. Holec (1981) supports this idea when reflecting on the importance of autonomy. His position focuses on the fact that in order to achieve freedom as individuals, one has to develop those abilities which enable him/her to take more responsibility in handling the diverse matters of the society he/she lives in.

Within a general perspective, autonomy can be used in different ways. It can refer to situations in which learners study on their own. It is used to refer to a set of skills that can be learned and applied in "selfdirected learning". Autonomy is also defined as a capacity we are born with which, in the majority of the cases, is suppressed or disavowed by educational institutions.

Benson & Voller (1997) highlight the concept of autonomy as a feature of individuals or of social groups. Autonomy as a characteristic of individuals is thought of as detachment from education as a social construction; while as a quality of social groups, autonomy entails reconsidering the distribution of power among the members of that social group. This dichotomy is connected to Benson's (1997) versions of autonomy. Benson argues that there are three different versions of autonomy, to wit: the technical, the psychological and the political. In the technical version, autonomy is regarded as "the act of learning a language outside the framework of an educational institution and without the intervention of a teacher" (p. 19). In the psychological version, autonomy is considered an ability learners have to take charge of their own learning. These two versions are closely connected to the perception of autonomy as a characteristic of individuals. On the contrary, the political version emphasizes autonomy as the control a learner exercises over the process and content of learning. Then, this last version is related to the conception of autonomy as a characteristic of social groups.

According to Little (1991), autonomy can be considered as "the capacity students have for detachment, critical reflection, decision making and independent action" (p. 4). Reflecting on the same issue, Dickinson (1995) emphasizes that autonomy is an attitude toward learning in which students are prepared to take responsibility for their learning. I would like to highlight this author's reflection on the various degrees of autonomy as self-directed behavior concerning decisions about what to learn, when and where learning should be developed, materials to be used, ways to monitor the learning process and how to carry out assessment of the process.

My own conviction is that autonomy is closely related to motivation; if people have a sense of autonomy, they may be more motivated by the things that are important to them. Then, intrinsic motivation enables the learner to be self-motivated. Supporting this argument, Dickinson (1995) highlights the role autonomy plays in students' motivation, as learners' independent and active participation in their own learning increases motivation and the process becomes meaningful.

After the exploration of various concepts on autonomy, it is important to highlight the idea of autonomy as a multidimensional concept which is linked to different disciplines. In psychology and philosophy, motivation is conceived as the ability a person has to act as a responsible unit within a social group. In politics, this concept is regarded as the freedom from external control. For the purpose of this study, autonomy is considered as the ability and attitudes students evidence when taking control of their learning process.

Factors to Consider When Exploring Autonomy in EFL Settings

Nowadays, education focuses its attention on methods of learning rather than methods of teaching; that is, students should be regarded as active agents vis-a-vis their own learning process, which would imply being the ones who make the most decisions about their learning. However, in most Colombian educational contexts, the traditional teacher-dependent paradigm is the one we may find in EFL classrooms.

Then, the dynamics within the EFL classroom are challenged as both teachers' and students' roles are expected to take on a new dimension.

In what can be considered the traditional vision of teaching and learning, teachers have been considered the owners of knowledge which gives them authority to act as directors, judges, controllers and even managers of all that happens in classrooms. Under the vision of autonomy in the teaching-learning process, teachers are perceived as facilitators, guides, counselors and coordinators. When students are faced with new challenges in their learning, teachers even coach them. As suggested by Aparicio, Benavides, Cárdenas, Ochoa, Ospina & Zuluaga (1995), teachers' capacities "must include identifying students' learning styles, conducting training in learning strategies and helping learners become more independent" (p. 116).

Along the same line, Cárdenas (2006) discussed what teacher autonomy involves and the way it supports the development of autonomous attitudes in students. This author highlights self-awareness, awareness, responsibility, challenges, participation, collaboration and the changing of roles as necessary elements when implementing change towards more autonomous individuals.

Under the new paradigm, teachers are to be more supportive and collaborative with students' processes, including the definition of their learning objectives based on the identification of specific needs; the definition of contents to be explored; the selection of methods and techniques and the process of evaluation of what has been achieved. Therefore, teachers will be valued according to the quality and type of relationship they have with learners. Furthermore, teachers' new roles imply getting actively involved in the process or construction and reconstruction of knowledge as well as providing challenging tasks which motivate students in the decision making process.

Exploration of Autonomous Learners' Characteristics

There are a good number of research studies which explore autonomous learners' characteristics. In this article I concentrate mostly on Latin American experiences as they share a common research focus with the experience I intend to describe. Among research exploring autonomous learners' characteristics, Chan (2001) reports on a research project that aims at exploring undergraduate students' attitudes and expectations of autonomous learning and how ready they are for undertaking this learning approach. The participants are 30 first-year undergraduates studying in a BA program in contemporary English language at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. The main findings of this study show that autonomous learning is perceived as a method in which a student decides what, how, when and where to learn. At the same time, participants are aware of their commitment to exploit the opportunity to learn on their own. It is important to highlight students' concept of autonomy as opposed to working in isolation. On the contrary, they appreciate the teacher's help when they face autonomous activities.

Cardona & Frodden (2001) developed a multi-site case study in two universities in English language teaching programs.

The researchers detected conflict arising from the mismatch between teachers' and students' expectations. Students who found it difficult to develop their autonomy wanted the teacher to be a know-it-all and resented teachers who gave students the opportunity to be active agents in their construction of knowledge. Similarly, more autonomous students conflicted with "traditional teachers" and blamed them for lack of collaborative work and not taking part in research. Teacher teamwork was necessary in order to expand teachers' and students' concepts of autonomy and to make decisions leading to bridging the gap between beliefs and behavior.

In the same spirit, Luna & Sánchez (2005) described the characteristics of autonomous learners in an EFL setting and identified dependent students as the most common profile in a group of prospective teachers. There are different characteristics autonomous learners may display when facing EFL learning experiences. Among these characteristics, it is worth mentioning involvement in the management of their learning process, the use of life-long learning strategies, and negotiation of various aspects of learning situations. Autonomous learning is a long process which needs time to be developed and means to be facilitated and fostered in EFL classroom settings. It is both the responsibility of teachers and students to work together for a better atmosphere and proper conditions so that learning processes can be more meaningful and long-lasting. The exploration in this section sheds light on multiple issues regarding the main aspects to consider in the study of autonomy in language learning.

Learning Experiences Which Favor Autonomous Learning

The research studies mentioned in this section emphasize the importance of bearing in mind what autonomous learning entails regarding the methodological aspect.

It has been proved that there are a number of conditions which favour autonomous learning processes. Thus, these research experiences were considered in the stages of planning and implementation of the current research project.

As a reference point of what should be conceived as ways to encourage students' autonomy, Nunan, as cited by Benson & Voller (1997), proposes five levels to foster students' autonomy in relation to the content and the process of learning.

Learners should be aware of the goals, contents and strategies of the materials being used so they can select content and procedures according to their personal objectives, learning styles and strategies. The next step implies learners' interventions in the modification or adaptation of the goals and content. Later, students create their own objectives. In the final stage students go beyond the classroom and search for opportunities such as self-access centers and continue their process of material creation.

This model was considered in the study reported by Zorro, Baracaldo & Benjumea (2005), that aimed at establishing the relationship between autonomous learning and English language proficiency.

In the same spirit, Scharle & Szabó (2000) provide a guide for teachers on how to develop a sense of responsibility in students causing them to take an active role in the learning process. Three main phases related to the autonomous learning process are presented. First, they propose an awareness raising phase which is directly connected to the way students can become autonomous learners. Second, they emphasize the importance of changing attitudes in our students, a topic which is related to the environment promoting autonomous learning. Finally, they focus on transferring roles through practical, graded, well-structured activities which for me shed light on strategies that students may use to become engaged in an autonomous learning process. We can observe the clear relation of this proposal with Nunan's levels of encouraging learners' autonomy.

Ruiz (1997) reports on an autonomous learning experience carried out at Universidad Pública de Navarra in the foreign language courses taught from 1991 to 1993. In this experience the threehour courses were complemented with the creation of a self-access center where students could count on diverse materials with which to work autonomously and the support of teachers who guided them on an individual basis in counseling sessions.

The results of the experience showed students' proficiency level progress as well as changes in students and teachers regarding their roles. Students assumed a more independent and curious role in relation to the language and the way to learn it. On the other hand, teachers gained understanding about the shift of control as a necessary condition to foster students' autonomy.

It is also important to highlight the research carried out by Sharp, Pocklington & Weindling (2002). This is a report of a qualitative project of study support in twelve secondary schools in the United Kingdom. Among the factors they reported, it is relevant to mention students' enjoyment, the possibility of getting help with learning, the absence of persons who would cause distraction, and the opportunity to be in a different atmosphere.

The study concludes that providing highquality study support is beneficial but requires commitment, investment and a clear understanding of its potential contribution to the work of the school. The conditions featured in the projects previously summarized are directly connected to the psychological preparation students may need in order to face a new learning situation, the type of materials and activities proposed for students, the selfaccess resources available to them, and the importance of aspects such as cooperative learning and reciprocal teaching.

The Context

I got involved in a year long research project in 2003 that sought to explore students' understandings of autonomy and the way those conceptualizations were evidenced in students' learning experiences inside and outside the classroom. The investigation was carried out in the program for obtaining a Bachelor of Education in Philology and Languages, with emphasis in English, at a public university located in Bogotá. The program takes an integrated approach to language teaching, which means it is communicative oriented and flexible in terms of methodology.

Participants

Twenty one students who attended a course of Basic English 1 were informed about the nature and purpose of the project. Nine, four female and five male students, volunteered to partake in this study. I decided on this criterion of selection as it has been proven to be practical, not biased and motivating for those students who may decide to participate in the project.

Participants were from 16 to 24 years of age and had a basic command of the target language. Even though they were full-time students, two of them had to work and one participant was in the last year of an engineering program at a different public university. They were from different places in Colombia which made the experience more interesting for both teachers and learners. They registered in the program and attended fifteen hours of English a week, three hours per day, which is a great advantage for their learning process. This type of course is usually directed by two teachers, one in charge of the first two hours of instruction and the other directs one hour of class a day. I had the responsibility of directing the first two hour session of instruction once a week during the second term of the academic year in 2003. I was also in charge of supporting students' work in the computer room. The possibility of using the computer room was part of the design of the research project though the regular courses do not necessary have this tool for their classes.

The five one hour sessions of instruction were guided by a professor who, once she knew about the nature and objectives of the project, offered her help and support in the process of data collection. My colleague's role was crucial due to the fact that in these one hour sessions students were given the option to go to the computer room. Then, students who wanted to continue working in the classroom could do so and the data collection procedure was undertaken by her. Also, those participants who wanted to work with the computer were able to do that as I was there in case they needed any support or help.

Instructional Guidelines for the Implementation of the Autonomous Workshops

Taking into account the nature of the study, a general instructional guideline was needed. The current plan is not a structured instructional design but a picture of classroom atmospheric characteristics which permitted this study to be carried out. The program for the Basic English I course is grounded in a topic based syllabus with specific objectives related to the macro communicative skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing and objectives at micro-skill levels: grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, stress patterns, and spelling. For the exploration of students' understanding of autonomy and the way it is evidenced in their learning, the following methodological principles were applied:

- Working with contextualized language and authentic material to carry out communicative and cooperative tasks.

- Considering the students as the center of the process and as active participants in the multiple activities through individual, pair and group work.

- Understanding the role of the teacher as that of a facilitator, guide, motivator, counselor and permanent co-evaluator in the learning process, creating a rich environment in order to facilitate the communicative process among learners and encouraging students' work.

- Giving students a great variety of opportunities to contribute with opinions, experiences and feelings in order to activate their background knowledge and use it effectively.

- Encouraging students to set their own objectives, to assume responsibility for their own learning and to develop learning skills, thus developing learner's autonomy.

In the three hours per week allocated for the development of the project, one autonomous workshop was implemented. A total of ten autonomous workshops were planned and developed. The workshops were designed based on the information collected through an initial questionnaire which aimed at exploring participants' previous English learning experiences, in general, and autonomous practices in particular. It also explored students' perceptions regarding their strengths and weaknesses as learners of English. The syllabus of the course in terms of topics, language functions and language skills was also considered for the design of the workshops. Then, every workshop included various tasks on the given topic. Students were provided with listening, reading, speaking, writing, functional grammar and vocabulary activities distributed on separate worksheets, so that they could decide on the task(s) they wanted to do. Some of the activities were designed by the teacherresearcher and some were adapted from various sources.

In every session, instructional objectives were stated by the teacher along with students' setting their personal objectives. The two sets of objectives were considered equally important and complementary. Then, I informed students about the various possibilities for autonomous learning tasks for that session, taking into account types of materials (pictures, posters, newspapers, stories, games), types of arrangements (individual, pair and group work), various sources (readings, listening material) and suggestions for extra-class activities (video, songs, internet, CALL). Students decided what materials to use, arrangements to work with and sources to resort to. During the sessions I was attentive to support participants in the development of the activities when necessary. After the time allotted for the task was over, I asked students to share their learning experience orally in a plenary session which served the purpose of data gathering on the way autonomy is evidenced through learning experiences carried out by learners in the EFL classroom. As a closing activity, the last part of the lesson was spent on written, sometimes written and oral, peer assessment and self-evaluation. Once the assessment process for the lesson was finished, the teacher provided students with multiple suggestions to be explored and implemented outside the classroom so that students could take advantage of the suggestions and make decisions as to how to go about the extracurricular activities proposed. Diagram 1 below shows the main characteristics of the autonomous sessions.

Research Method and Instruments for Data Collection

As the aim of the study is to explore what the participants' learning experiences inside and outside the classroom contributes to our understanding of learner autonomy, I selected case study as the research methodology to undertake since it provided me with the opportunity to observe and analyze this situation in depth. Merriam (1988) conceives a case study as a research design used systematically to study a phenomenon by approaching it from a holistic perspective.

Within this paradigm, the researcher is the primary instrument as we are part of the context to be interpreted. Thus, the type of observation was that of participant observation as I engaged in the activities set out to be observed. Considering the main aspects of this project, I determined that the principal instruments to collect proper information were basically the following six: field notes, video recordings, questionnaires, recorded audio interviews, students' logs and audio-recorded plenary sessions.

All the instruments were designed and piloted during the first semester in 2003 and were applied in the second semester of the same year. Data were systematically collected in every three-hour session a week over a period of eleven weeks; thus, rich data could be gathered making it possible to triangulate the information. Two types of triangulation were implemented. First, methodological triangulation is evident as six ways to collect information on the same issue were used. Secondly, there was investigator/researcher triangulation as I was given the opportunity to have the support of a colleague in the data collection process, specifically with field notes and video recordings.

Field notes were a primary source of data collection. I took notes on-site as I was working with the participants. A special format was used in this process (See Appendix 1). It included information on the number of the session, the place, the duration of the observation process, the name of the observer and the date of the observation session. The format also included a section to takes notes on what participants did during the autonomous sessions and a parallel column for the researcher to write initial comments on what the notes may mean taking into account the research focus. Sixty-six formats were used during the development of the study.

The second instrument was video recordings of the sessions. This was a secondary instrument as it became a supportive device to complement and enrich the note making process. As a result, six video cassettes were recorded, transcribed and analyzed.

An initial instrument for data collection was a questionnaire1 which was elaborated, piloted, readjusted and implemented (See Appendix 2). The main purpose of this instrument was to explore students' learning experiences and their beliefs related to their processes of learning English as a foreign language. This instrument provided the researcher with valuable information for planning the autonomous workshops as it informed me about students' previous experiences and their needs and preferences regarding activities and materials. Likewise, the information collected through this tool shed light to guide the interviews.

The fourth instrument used for data collection in the research process was a semi-structured interview2 (See Appendix 3). In this type of interview a schedule is prepared, but most of the questions are open. Such protocol has certain prompts in terms of comments or follow up questions so the interviewee's time is respected (Wallace 1998). An adaptation of Seidman's phenomenological interviewing was designed. The main objective when using this type of interview is "to have the participant reconstruct his or her experience within the topic of study" (Seidman 1998, p. 9). The questions designed dealt with exploring students' affective dimension of their learning process, and students' reflections and understandings in two main areas: self-exploration as learners and their understanding of autonomy.

Another instrument used was students' logs3, which can be defined as structured journals as they follow a particular format previously established. Student logs were developed with the guidance of certain headings such as what students learned in that specific lesson, factors that eased the learning process and ways in which students have worked on problems or difficulties in their process. Finally, some space for afterthoughts or comments was provided so students could also reflect on what they did and set a plan of action to overcome possible difficulties. Each participant wrote one entry per week, from the last week in August to the last week in November, 2003. One hundred and five entries were collected along the research. This type of guided diary may be perceived as a tool for fostering students' autonomy as they are asked to examine their processes and reflect upon what they have experienced both in and outside the classroom.

The last instrument for data collection was the audio recording of plenary sessions4. As stated before, once each autonomous session was over, participants were asked to participate in a plenary session which aimed at unveiling students' reflections on the decisions they had made during those autonomous practices. Plenary sessions were also used by the participants as a space to express their feelings and concerns regarding the type of activities they had decided to develop and the outcomes of such practices.

Findings

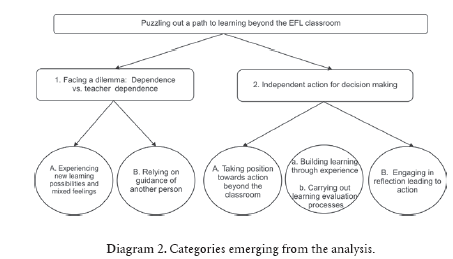

After taking some time to decant data, we analyzed and categorized these using Strauss & Corbin's theory (1990). The key concept in their proposal is the coding procedures which are conceived as plans of action by which data are cleft, conceptualized and recombined in new, different ways. Once this procedure was completed, one core category, two main categories and four sub categories with defined properties emerged. Diagram 2 represents the categories and their relationships.

To guide the reader in this section, some abbreviations were used to indicate the source of each piece of evidence5 presented. FN stands for field notes, V stands for video recordings, L stands for students' logs, C stands for audio -recorded interviews and PS for plenary session.

Puzzling Out a Path to Learning beyond the EFL Classroom

This core category refers to students' understanding of autonomy as a road to walk on along their learning process in and outside the classroom. On the one hand, participants in this research study were given the option to exercise their autonomy in various autonomous sessions. On the other hand, students were encouraged to share those experiences they created or looked for in order to contribute with their English learning process outside the classroom.

There are two main categories explaining this phenomenon. On the one hand, participants struggled between showing dependence on the teacher or on other individuals who are part of the learning environment and being detached from the teacher and leading their own learning process. On the other hand, participants revealed independent action when facing decision making processes. Thus, autonomy, as expressed by Benson & Voller (1997), has an individual and a social dimension. Let us examine the first aspect which defines this core category.

Facing a dilemma: Independence vs. Teacher dependence

This category refers to the predicament participants faced when given the option to handle, up to a certain point, their learning process. Most participants went through a mixture of feelings when tackling this new proposal to carry out tasks. They were uneasy as they had not been exposed to a similar approach to learning in a classroom setting. This emotional aspect of both teachers and participants is highlighted by Aparicio et al (1995) when they presented a proposal to promote awareness and confidence in teachers and learners when facing this new conception. Through the analysis process, two subcategories were identified. I called the first one experiencing new learning possibilities and mixed feelings. The second one is relying on other people's guidance.

Experiencing new learning possibilities and mixed feelings

When participants faced the new learning experience they had a dilemma between detached work and teacher dependence. This entailed going through a great variety of learning possibilities experiencing multiple feelings. Sometimes participants experienced happiness as evidenced during an activity based on a board game: "L: 'and now what happens? M: 'to jail' everybody in the group started laughing at the analogy with a local game called 'parqués' (FN 28). Whereas in certain occasions they showed confidence: "F starts working with the function - preposition guide. He works alone. No hesitation. He develops it completely, including the writing" (FN 37).

The evidence also shows that some students' attitudes reflect passivity when confronting a listening exercise. During the session on September 3, when a group of students were developing a listening exercise, this passive attitude was observed: "Ma came in at 3:10 and joined the group working on the listening exercise. In this group Ca was handling the tape recorder. Cl finished first and Mi began correcting the exercises with them. Pa and Le just looked and listened. They remained silent." (FN 18)

During the autonomous sessions, there were even moments of frustration due to feeling unable to carry out a task under students' personal criteria: "C starts with the puzzle (vocabulary). He frowns and hits his desk. He goes to check something in his course book" (FN 37). At first instance I interpreted the situation as if the student had not felt comfortable with the material. In order to avoid drawing conclusions based on assumptions, the same participant was asked about this specific event during the plenary session and he acknowledged getting mad at himself for not being able to remember the pieces of vocabulary needed for the exercise: "It was frustrating to begin developing the exercise and .. I couldn't remember... I was not able to remember" (PS 6).

My own interpretation of the findings emerging in this category is based on two main aspects. On the one hand, in the autonomous learning experience, students assumed various positions such as active participation or passivity, depending on the way they approached this paradigm of work. Aspects such as their language proficiency, their personal preferences and learning styles, and some personality features influenced students' decisions during the autonomous sessions. As evidenced before, some students showed confidence or passivity due to the material they selected.

Participants felt more secure developing a grammar or vocabulary guide than one based on a listening exercise as they usually reported more difficulty understanding listening texts. Participants also made decisions based on their learning styles; for instance, authority-oriented learners evidenced a greater need of teacher's support than independent learners. This analysis is validated with the information collected through the first instrument used, the initial questionnaire. Regarding the first item of the questionnaire, students reported practicing the language as the most efficient way to learn it (56%); 34% of the learners stated that meaningful learning and the possibility to enjoy the learning process were key factors in efficient learning. A low percentage of participants (12%) considered the use of various resources to practice the four communicative skills as a way to learn a language.

Fifty-six percent of the participants had had the support of friends, teachers or foreigners in the development of their English proficiency. On the contrary, 44% of the students said they had not had any support. In relation to the resources they use in their English learning process, 67% of the students reported the use of listening materials, especially movies and music, 56% said they read different types of texts such as readers or technical books, 12% reported the use the Internet as a tool for practicing and 12% of the participants said they took advantage of having foreign friends with which to practice speaking.

In relation to students' perception of their strengths and weaknesses in the language, 45% reported having a good command of vocabulary, 23% perceived themselves as efficient listeners; 34% thought their motivation and commitment were the main advantages in their learning process. Only one student considered that his analytical learning style had been of great help in understanding the mechanism of the language. Regarding participants' weaknesses, 34% of the learners reported having limitations with their pronunciation, and 23% pointed out grammar and writing as their main limitations. Other problematic areas students mentioned were speaking, lack of discipline and low self-confidence.

Considering extracurricular activities, 67% of the students said they carried out extracurricular activities. Listening to music and watching movies were the most common independent practices. Reading, speaking and developing assignments were also common activities (12%) among the participants. Two students considered the lack of time, motivation and not having the direction of someone knowledgeable as the main reasons for the absence of independent work.

On the other hand, while students experienced and exercised autonomy, they moved constantly from working independently to looking for support from different individuals who were part of the work dynamics. Participants looked for support from both the teacher and their peers. Such interaction was framed by aspects such as the participants' decisions concerning the activity selected, the material itself and the way to tackle it.

Regarding the activities selected, students evidenced the need of more support for writing exercises, listening tasks and Internet site activities. Participants also asked for support when they selected materials such as crossword puzzles or speaking tasks and topics. As evidenced in the questionnaire analysis presented above, this situation originated from a lack of previous learning experiences with this kind of resources. Furthermore, learners considered that, concerning speaking activities, they needed someone- the teacher or a knowledgeable peer-to provide constant feedback on their pronunciation and accuracy.

Relying on other people's guidance

The second subcategory identified was: Relying on Other People's Guidance. The uncertainty this new experience brought made students move constantly between working by themselves and depending on other individuals who were present in their learning experiences. Sometimes, they wanted to consult regarding their decisions.

In the first two sessions participants expected me to direct them about what to do and how to do it: "M: 'teacher, which activity should I do first?' L: What do you want me to do?" (FN 1). They also asked for clarifications of their doubts: "M asks me about the use of 's with names such as James", "M asks me about how to define oil. She is developing the reading guide" (FN 3).

In the last two cases we can deduce that students' dependence was caused by a lack of using leaning cognitive or meta-cognitive strategies such as resourcing, grouping or deduction (O'Malley & Chamot, 1990).

Participants also looked for teacher support with technical problems: "M is surfing in the English Club internet site- 'Teacher, please, help me... I don't know how to get here -pointing to a specific link in the site" (FN 14). Likewise, teachers are addressed as a source of unknown vocabulary: "M: 'What's the translation of weeknight?' although he had the dictionary in his hands" (FN 22).

As previously stated, the teacher's support, help and guidance were needed for different reasons. Participants looked to the teacher to accompany their decision making process regarding the selection of materials and exercises, as well as in the development of activities. The teachers became guides and advisors during the various decisions students made in the autonomous sessions and those carried out outside the classroom. Teachers were also regarded as sources of knowledge and were constantly consulted to clarify doubts. Similarly, as Chan (2001) reports, participants shared the idea of regarding the teacher as an evaluator, as shown by Ka in this interview excerpt when she was asked about her perceptions on the autonomous sessions:

26 I know what autonomous work is. All in all it is necessary,

27 It is also necessary that you assess us, I don't know, I mean…

28 You can make….a, yes, an evaluation on what each one of us does.

(C 3, p. 2, L 26-28)

The transformation of the teachers' roles in the methodological framework that autonomous work entails is evident. Autonomy does not necessarily imply developing learning processes in isolation, under no guidance or support at all. On the contrary, in autonomous work, teachers are called to assume various important roles which have a great influence in the results of this experience. The following is an example of a participant who clearly states the importance of a figure who guides students' autonomous processes.

264 T: Do you think that it is necessary for the teacher to be there? The English teacher?

268 Al: Well, I do believe that the language teacher or someone who knows the

269 language should be there, because (inaudible) one may turn to him (inaudible)…

270 In fact, it would be a great idea to count on tutors for these sessions.

(C 4, p. 23, L 264, 268-270)

Along the course this subcategory evolved in two directions. On the one hand, some participants maintained their need to have some support along the process that autonomous work entails. On the contrary, some other students became more independent in specific instances such as when developing extracurricular activities. Some factors which influenced this position are evident. First, students' learning preferences are a key aspect to bear in mind. There were some participants who preferred to work alone as stated by Ca in the interview when being asked about his work preferences during the autonomous sessions:

172 C: I don't know. This is, this is a very personal thing.

173 Sometimes I prefer to work on my own, I mean

174I prefer to do the stuff by myself

175 in order to do them well, I do them all alone.

179 It is the way I am.

(C 3, p. 19, L 172 - 175, 179)

Along the process students went through when looking for various possibilities to self-direct their learning, a systematic need to take independent action towards decision making was acknowledged. Thus, a second category related to this aspect that emerged in the analysis will be examined in the next lines.

Independent action for decision making

Little (1991) states that when defining autonomy one must consider aspects such as the capacity learners have to work independently, to develop critical awareness, and to make decisions which guide their further action. These are key aspects which explain this category. In the current study, independent action for decision making refers to students' understanding of autonomy as taking a position to lead their learning process. Students started to make decisions regarding multiple aspects of both the workshop sessions and extracurricular activities.

The analysis of the data collected showed that when students engaged in independent action, two big constructs emerged. First, students took a position towards action which was evident in a process of decision making regarding their practices. The second construct gears towards students' engagement in reflection when facing learning experiences in and outside the classroom.

Similarly, these constructs are defined by two common dimensions. One the one hand, students built learning through experience which permeated decision making and reflection processes. On the other hand, participants carried out learning evaluation based on the decisions made and the additional reflection on them. I will proceed to describe each one of these subcategories.

Taking a position toward action beyond the classroom

Regarding independent action, participants decided to practice English in and/or outside the classroom, or not to practice at all. Data analysis revealed four main factors which influenced these students' decisions. Students decided not to develop activities concerning their English learning due to constraints of time or other priorities different from academic ones.

The following instance is the account of a participant in his first log. Making reference to some written grammar exercises, Da accounts for his decision of not completing them: "I think this exercise is very important, But I also consider it is necessary to complement it with some speaking practice so that you can internalize the information. I didn't do it because I didn't have time" (L 8).

Likewise, J M reports on the same factor in his fourth log, "I couldn't spend time to do any extracurricular activity. It was the sports week" (L 28).

Another issue to consider is the difficulty students faced to carry out some of the activities proposed in the autonomous sessions caused by their novelty as stated by Ed in his first log on August 22nd: "Because it is the first time I develop a practice like this one, I had problems to listen and interpret certain words" (L 4). Personal commitment and self-demand was an aspect participants highlighted as a cause for lack of motivation. In this regard Pa reported:

"Little by little I have discovered and understood that learning implies personal commitment, then, the success or failure depends on oneself. It is really difficult to self-regulate" (L 25). On the contrary, participants' needs were revealed as a crucial aspect to develop autonomous practices. The following is an excerpt of extracurricular activities carried out by Al during the fifth week of the study: "This week I have been practicing English a lot because I have been looking for an opportunity to travel to England to study. I practiced with a pronunciation book…" (L 43).

In the analysis of data, decision making is one of the most consistent elements which evidenced students' understanding of autonomy in their real practice.

Considering Dickinson (1995) and Chan's ideas (2001), participants in this project make decisions regarding what, how, where and when to develop the activities provided in the autonomous sessions or the ones participants looked for. In relation to decisions on activities and the methodology to develop them, a relevant piece of data is found when some students were in the computer room: "A enters games in EnglishClub.com; she starts developing a crossword. P is downloading an exercise from Englishzone.com about simple present and is copying it in a diskette. Al is working in the English program 1, he first listens to the photo story and starts clicking on specific words to listen to their pronunciation" (FN 5).

Participants also decided who to work with using varied criteria. In some cases students looked for peers who were much like themselves:

143 Jo: Ah, I work with Nat because she makes me laugh and yeah, she is

144 less stiff. For example, I have worked with other partners

145 and...++ Once I was working with Ca and I told her

146 'let's stop doing this exercise and let's go outside' but she said 'No! We have to do this'.

(C 4, p.6, L 143-146)

Students also took into account the level of English proficiency they considered they had in order select their partners:

152 I also prefer to work with Nat because we have a similar level. With An,

153 with An I feel good, but she doesn't ++ doesn't have the vocabulary

154 so, she notices it and walks away to work by herself.

155 I always tell her 'Hey! Come with us' because I feel bad for her

156 but then I think…. It is better that way because we can practice speaking better,

157 and that is because Nat and I speak easily.

(C 4, p. 6, L 152-157)

When students decided to work in pairs or groups, they adopted certain roles or positions I consider worth mentioning. Some of the learners acted as leaders of small groups: "J used Spanish to explain some things the members of the group didn't understand. She performed as a guide of the activity" (FN 9). Another role assumed was of directing specific activities: "Pa manages the tape recorder. She says 'again?'… Pa wanted to compare her answers, but the group decided to listen to it once more" (FN 11). Other participants preferred to model for their peers: "Ma is telling the rest of the group what she understood -when developing a listening activity- she reports on different pieces of information. She models the pronunciation" (FN 31).

Decisions regarding the place to work were also made: "D, A, Nat and Jo are outside, on the steps. They are talking about the person of their dreams. They are using English." (FN 18) In this case participants explained their choice of place on the grounds of respecting the silence their peers seemed to need in order to develop the activities. In other instances learners decided to take some of the materials home or to look for materials or learning opportunities in resource centers such as the one the British Council has. Some evidence enlightening this analysis was provided by Al when asked about the reasons for his preference to work at home:

274 I prefer to go there (the British Council resource center). It is connected to

274 what I told you once, in the plenary; I feel freer when I handle my time. Then

275 I do not go there straightforward, I first go home, have lunch, and then

276 I go there. I start to develop the stuff and other things I wanted to do, so…

277 I notice I work harder +++ I felt free outside the classroom.

(C 4, p. 25, L 274-277)

As it was mentioned in the explanation of the second category, independent action for decision making, reflection and inquiry was also present along the process of facing learning experiences in and outside the classroom. I will proceed to describe and exemplify this subcategory.

Engaging in reflection leading to action

Being able to engage in reflection processes is at the core of autonomous learners' characteristics (Little, 1991).

Students engaged in reflection upon significant aspects of their learning process as well as on their view of the autonomous sessions carried out in this study. Regarding reflection upon students' learning process, data analyzed showed how extracurricular activities as well as activities carried out during the autonomous sessions lead participants to ponder their strengths and weaknesses in relation to their English proficiency level as well as in the way they tackled the activities. Let me exemplify it with some evidence. In her log entry number seven, Jo reports: "I studied the pronunciation symbols, because my main difficulty is the symbols. But, in the long run it was the same. I didn't feel any progress… I guess it is a process" (L 59).

Ya also reported on her difficulties:

"Regarding my difficulties I have to say that self-observation is an important exercise for me. I am always trying to identify my mistakes and trying to find the things that I need to improve. I already found (for example) that I need more speaking and vocabulary and I need to remember a lot of things that I have probably forgotten". The same participant kept on explaining the way personality factors have a direct influence on her difficulties with the language:

"Another important aspect, talking about my mistakes, is the intensive influence of nervousness. I think that I am a shy person. Before I was extremely shy and now I am less shy due to the self-observation" (FN 6, 7).

Students' reflection became a step which led them to take action regarding their process as shown in the following excerpt by a learner who shared the experience of attending a congress on English:

"Definitively, what I have to overcome is fear of speaking in English, because though I understood most of what people said to me, I replied in Spanish. I guess this limitation can be tackled just by speaking and that is going to be my main objective" (L 67).

Once learners identified their limitations, they used a variety of strategies to overcome them. Among the most common strategies students used, systematic practice, repetition, memorizing, revising, association and note taking are worth mentioning. The coming examples account for the way different participants worked on their difficulties. Cla: "The way I worked on my limitations was trying to practice more, in my case listening" (L 5); Ja: "I check new vocabulary or words I have forgotten on a daily basis. I compare the words I listened to in class or outside the classroom with the phonetic transcription in the dictionary in order to correct pronunciation" (L 57). Pa: "I worked on my difficulties repeating words from a reading or a listening exercise on a given topic and then I associate the way they are written with the way they are pronounced" (L 16).

An interesting issue of reflection is the way participants viewed the autonomous learning sessions. All the students who were asked about their perceptions on this topic agreed about the benefits it provided and how comfortable they felt with the experience:

176 Ca: I like them (the autonomous sessions) I really like them

177 T: Why do you like them?

178 Ca: Because +++ in my opinion they are fulfilling the objectives

179 you posed ++ that is, to be able to discover what is wrong and all the stuff

182 I work by myself, alone, nothing else matters, I mean, it is like

183 to unveil one's soul and, yes, one learns.

(C 3, p. 7, L 176-179, 182-183)

In light of the data analysis process and regarding the two subcategories previously explained -taking a position towards action beyond the classroom and engaging in reflection leading to action- we can observe two dimensions which permeated both components. On the one hand, the process students undertook to make decisions and to carry out reflections leading to action allowed and, at the same time, led students to build their own learning through experience. On the other hand, students got involved in a dynamics of the evaluation of multiple aspects regarding their learning process. These dimensions will be addressed in the next paragraphs.

Building learning through experience

When students decided upon practicing English in and outside the classroom, they built up learning continuously.

This construction and reconstruction of knowledge, which has become a tenet of critical pedagogy, occurred through multiple phenomena. These dynamics will be explained in the coming paragraphs.

Students built knowledge through the autonomous experience taking advantage of aspects such as their background knowledge, the possibility to set clear purposes and objectives, the various opportunities to practice the language, the techniques and strategies to develop multiple tasks and the students' capacity to acknowledge their difficulties and to find ways to overcome them.

Students used linguistic knowledge to tackle tasks in order to construct knowledge, as reported in the field notes. The following example refers to the way a student carried out a listening task. "When An completed the listening exercise, she decided to translate part of a song: 'pero yo no te puedo sentir cerca ahora... No, thought is the past tense of think" (FN 2). This excerpt evidenced the way this participant relied on some knowledge of the language in order to cope with a task.

Setting clear objectives and having achievable purposes is a second dimension of both decision making and students' reflection. Participants acknowledge the importance of having clear objectives when engaging in the activities proposed in the workshop as well as in the exercises carried out outside the classroom. An interesting piece of evidence regarding this aspect can be found when a group of students was doing a listening task. Their objective was to identify the use of prepositions of place through a listening exercise. They decided to start working on an individual basis:

"Ma and Ka started with the first listening exercise. Ka: "Again". Ma nods her head. Ka: "It is three words - again - near to the City Hall." Ka talking to Pa: "Is interesting?" Pa: "Yes." Ka: "Is in the park or on the park?" Ma: "In". They listen again to check and nod their heads" (FN 38).

The next dimension relates to various strategies and tools students implemented while developing tasks in and outside the classroom. As highlighted by Dickinson (1995), being autonomous implies developing an attitude toward learning in which students get prepared to take responsibility for their process. Therefore, students are called to decide upon the way to direct their learning and the resources to do so.

In the excerpt below we can perceive how a student used systematic work in order to develop different activities they selected during the sessions held in the computer room. "Ale is working on a photo story. He pauses in every scene and then clicks on pronunciation. He asks about the expression 'Does that ring a bell?' he says 'I don't see a bell' he asks me for the explanation of it" (FN 6).

A key element in students' knowledge building process is their capacity to account for the outcomes of their autonomous learning experiences. This core aspect will be accounted for in the following paragraphs.

Carrying out evaluation processes

Participants showed a constant need to evaluate both their decisions during the autonomous sessions and their own learning process. In order to assess their learning process students use different tools and varied forms. Thus, participants' evaluation process was made through peer correction: "K, M and C did the listening before and now are comparing their answers" (FN 26); "K: 'Again?' M nods her head - they are completing a chart about places, their location and interests. K: 'It's three words, again?' They listened to it again. 'Near to the City Hall' (FN 38).

Another tool used to assess their performance was the answer key. Initially, the activities proposed were adapted and, due to the amount of activities and all the work that having them ready entailed, I did not think about having an answer key for each one. Later in the process, during a plenary session, a student suggested having answer keys. Once answer keys were available, most learners used them as a tool to evaluate their performance: "K completes the first exercise on reading and grammar, the activity was individual, then she keeps on doing all the exercises. Later she goes to check with the answer key" (FN 12). "Most people are doing grammar exercises. Paul is correcting some listening exercises. He has just finished, he is checking with the answer key" (FN 42).

In a few cases students wanted the teacher-researcher to assess the performance of the task proposed for the autonomous workshop sessions: "M asked me to check her exercise copy. I did it and it was all correct" (FN 5). Finally, participants used computerbased evaluations in order to assess their own learning progress: "A continues with another type of quiz but in the same web page" (FN 33).

The examples provided so far have illustrated the idea that constant evaluation processes that look for assessing students' progress comprise a key element within an autonomous framework. Participants acknowledged the importance to evaluate multiple aspects entailed in autonomous work as well as their performance in the activities provided during the autonomous workshop, and the ones they developed outside the classroom.

Conclusions and Pedagogical Implications

EFL students' understandings of autonomy were evidenced as the way they find a road to learning by expanding on the boundaries of the classroom setting. Students evidenced their conception of autonomy in they way they faced the multiple activities proposed during the autonomous workshop and the ones they looked for outside the classroom.

Autonomous work is a new paradigm for both teachers and learners. Being a new model, autonomous work generated uneasiness as learners faced a predicament between detachment and teacher dependence. A variety of feelings and states emerged. In certain specific moments of this process students felt happy, uneasy, confident, and even frustrated. We as teacher must be prepared to support students along the process so that they can face it easily and comfortably.

In terms of the dilemma students faced within the new paradigm -autonomous learning -the current study showed aspects that contrasted with research made by Thanasoulas (2000) regarding autonomy as a situation in which learners study on their own, without the intervention of the teacher. The findings of this study support the idea of autonomous work as another way in which teachers participate in students' learning process (Chan, 2001).

Within this framework, teachers are called to be guides, supporters, co-evaluators, and providers of materials and tasks which encourage students' decisions to work on them. Students' role is a more active one.

They are central in their learning process as they are the ones who make most of the decisions regarding the selection of materials and activities, the ways to develop them, partners to work with, places in which to carry out activities, strategies to use, and tools to evaluate their performance.

Another significant aspect of this study is students' understanding of autonomy as an opportunity to take independent action in order to exercise decision making dynamics. There are some important factors that play a crucial role when students are faced with decision making regarding their learning process. Motivation and students' needs and plans regarding the use of the foreign language are among the most relevant factors students' prioritize when organizing their work.

A point related to decision making is students' position towards action beyond the classroom. As described and analyzed above, in some instances learners decided not to carry out extracurricular activities due to the priority given to other academic activities or to a lack of time devoted to activities which might have fostered their English learning process. On the contrary, when participants decided on multiple aspects of learning, they assumed various roles depending on the type of decisions made. Some learners might act as leaders of their partners while others might model for their peers. In this sense, I coincide with the idea of autonomy as a feature of social groups (Benson & Voller, 1997).

Continuous reflection leading to action is a nourishing component of autonomous learning. Working within an autonomous framework promotes students' engagement in reflection regarding core aspects of their learning process as well as relevant features of autonomous experiences. In the current study, students reflected upon their strengths and weaknesses. A second issue of reflection was connected to the way learners perceive the target language and the importance of developing communicative competence. Students' motivation and sense of achievement were also foci of reflection as well as their limitations when tackling specific activities proposed or carried out outside the classroom.

An important dimension of autonomous work is the dimension of construction and reconstruction of knowledge which is essential in autonomous work. Learners build knowledge through multiple phenomena such as activating their background knowledge. A second aspect to highlight is the possibility to set clear purposes and objectives. When students are encouraged to set their own goals related to specific functions, they engage in a rich dynamics of setting personal objectives The last aspect in the construction of learning through experience is related to the techniques and strategies students implemented in order to develop the tasks they selected in the autonomous sessions as well as in extracurricular activities. When tackling a task, students used strategies and techniques such as systematic practice, repetition, association, memorization and note taking. The type of strategy selected and implemented is closely connected to students' learning preferences and to the type of activities participants decide to develop.

In this study, evaluation processes proved to be a core component of students' understanding of autonomy. Students carried out evaluation at two different levels. On the one hand, learners evaluated their learning experiences and the results of the activities and tasks in and outside the classroom. Here, students used peer correction, the teacher, answer keys and computer-based evaluation forms in order to assess their learning experiences. On the other hand, students evaluated aspects such as the way activities were developed, the materials used and the importance of the autonomous sessions held in the study.

All participants agreed on the benefits that autonomous sessions had in their learning experience. Autonomous sessions were regarded as very interesting spaces to exercise decision making related to most of the components of learning. As expressed by one of the participants, autonomous sessions allowed students to discover their weaknesses and to find a way to overcome them. It was the opportunity to unveil their souls.

The implementation of autonomous work requires a proper atmosphere where students and teachers feel comfortable and supported when engaging in a new teaching-learning paradigm. Thus, it is essential for spaces to be created so that students and teachers are able to express all the feelings they go through when facing a different learning dynamics. On the basis of this teacher-research, I have learned that plenary sessions are relevant spaces in which students could reflect upon the experience they lived. They had a cathartic dimension for both students and teachers.

* This paper reports on a research study conducted in 2003 and constituted the thesis of my master's studies.

1 The questionnaire was originally in Spanish taking into account both the purpose of the instrument and the participants' Basic English proficiency.

2The interview was done in Spanish taking into account both the purpose of the instrument and the participants' Basic English proficiency.

3 Students' logs were kept in Spanish taking into account both the purpose of the instrument and the participants' Basic English proficiency.

4 Plenary sessions were held in Spanish taking into account both the purpose of the instrument and the participants' Basic English proficiency.

5 Evidence was translated into English so that non Spanish-speaking readers would have access to this information

References

Aparicio, B., Benavides, J., Cárdenas, M. L., Ochoa, J., Ospina, C. & Zuluaga, O. (1995). Part II. Teaching to Learn. Colombian Framework for English COFE Project. London: Thames Valley University. [ Links ]

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18-34). London: Longman. [ Links ]

Benson, P. & Voller, P. (1997). Autonomy and independence in language learning. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, R. (2006). Considerations on the role of teacher autonomy. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 8, 182-202. [ Links ]

Cardona, G. & Frodden, C. (2001). Autonomy in foreign language teacher education. IKALA, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 6, 11-12. [ Links ]

Chan, V. (2001). Learning autonomously: The learners' perspective. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 25(3), 285-300. [ Links ]

Dickinson, L. (1995). Self-instruction in language learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy in foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon. [ Links ]

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy: Definitions, issues and problems. Dublin: Authentik Language Learning Resources Ltd. [ Links ]

Luna, M. & Sánchez, D. (2005). Profiles of autonomy in the field of foreign languages. PROFILE, 6, 133-140. [ Links ]

Merriam, S. (1988). Case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publications. [ Links ]

O'Malley, J. & Chamot, A. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Ruiz, Y. (1997). Aprendizaje autónomo en la adquisición de segundas lenguas: una experiencia en la Universidad. Didáctica, 9, 183- 193. [ Links ]

Scharle, A. & Szabó, A. (2000). Learner autonomy. A guide to developing learner responsibility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Seideman, I. (1998). Interviewing as qualitative research. A guide for researchers in education and social sciences. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

Sharp, C., Pocklington, K. & Weindling, D. (2002). Study support and the development of the selfregulated learner. Educational Research, 44(1), 29-41. [ Links ]

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. London: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Thanasoulas, D. (2000). What is learner autonomy and how can it be fostered? Retrieved August 24, 2008, from The Internet TESL Journal Web site: http://iteslj.org/Articles/Thanasoulas-Autonomy.html [ Links ]

Wallace, M. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Zorro, I.; Baracaldo, D. & Benjumea, A. (2005). Autonomous learning and English language proficiency in a B. Ed. in Languages Program. HOW, 12, 109-123. [ Links ]