Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Profile: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development.

Print version ISSN 1657-0790On-line version ISSN 2256-5760

profile no.10 Bogotá July/Dec. 2008

Error Analysis in a Written Composition

Análisis de errores en una composición escrita

David Alberto Londoño Vásquez*

Institution Universitaria de Envigado, Colombia

* E-mail: davidlondono@coomevamail.com

Address: Carrera 27 B No. 39 A sur 57 Centro de Idiomas Envigado, Antioquia, Colombia.

This article was received on November 27, 2007 and accepted on April 30, 2008.

Learners make errors in both comprehension and production. Some theoreticians have pointed out the difficulty of assigning the cause of failures in comprehension to an inadequate knowledge of a particular syntactic feature of a misunderstood utterance. Indeed, an error can be defined as a deviation from the norms of the target language. In this investigation, based on personal and professional experience, a written composition entitled "My Life in Colombia" will be analyzed based on clinical elicitation (CE) research. CE involves getting the informant to produce data of any sort, for example, by means of a general interview or by asking the learner to write a composition. Some errors produced by a foreign language learner in her acquisition process will be analyzed, identifying the possible sources of these errors. Finally, four kinds of errors are classified: omission, addition, misinformation, and misordering.

Keywords: Error, mistake, clinical elicitation research, incidental sample

Los aprendices comenten errores tanto en la comprensión como en la producción. Algunos teóricos han identificado que la dificultad para clasificar las diferentes fallas en comprensión se debe al conocimiento inadecuado de una característica sintáctica particular. Por tanto, el error puede definirse como una desviación de las normas del idioma objetivo. En esta experiencia profesional se analizará una composición escrita sobre "Mi vida en Colombia" con base en la investigación a través de la elicitación clínica (EC). Esta se centra en cómo el informante produce datos de cualquier tipo, por ejemplo, a través de una entrevista general o solicitándole al aprendiz una composición escrita. Se analizarán algunos errores producidos por un aprendiz de una lengua extranjera en su proceso de adquisición, identificando sus posibles causas. Finalmente, se clasifican cuatro tipos de errores: omisión, adición, desinformación y yuxtaposición sintáctica.

Palabras claves: Error, equivocación, investigación a través de elicitación clínica, muestra incidental

Introduction

In this investigation, based on personal and professional experience, I focused on a composition entitled "My Life in Colombia".

I followed clinical elicitation research, by asking the research participant to produce some data which was then analyzed. This incidental sample is taken from one of my students. Her name is Erika and she is a high-beginner student (level 2 at a public university in Antioquia, Colombia). She has four two-hour lessons a week, from Tuesday to Friday in the morning. She is 18 years old and does not feel confident with her English learning process, but her professional goals require a good command of it. She participates in all the class activities and I consider her a responsible student. Even though she commits the same errors in both oral and written English, she often tries to express her ideas and feelings in English. In order to highlight her errors and how they work, I use the surface strategy taxonomy to describe them.

Literature Review

Learners make errors in both comprehension and production. Corder (1974, p. 25) has pointed out: "It is very difficult to assign the cause of failures in comprehension to an inadequate knowledge of a particular syntactic feature of a misunderstood utterance". Indeed, an error can be defined as a deviation from the norms of the target language. In this literature review, firstly I briefly show the five steps in error analysis suggested by Corder. Secondly, the collection of a sample, in fact massive, specific and incidental samples, is briefly mentioned.

Thirdly, I introduce the identification of errors and its four divisions. Fourthly, the category taxonomy and surface strategy taxonomy, which we can apply to a corpus, is presented. Fifthly, I continue with the explanation of error, showing the two main positions on the source of error in foreign language learning. Finally, I introduce the evaluation of ideas as the last step in errors analysis. Let me start, then, with Corder's five steps in error analysis.

Corder (1974) suggests that many of the researchers who carried out error analyses in the 1970s continued to be concerned with language teaching. Indeed, many of those who attempted to discover more about L2 acquisition thought the study of errors was itself motivated by a desire to improve pedagogy. That is why Corder proposes five steps in error analysis research in order to reach that objective. These steps are:

1. Collection of a sample of learner language

2. Identification of errors

3. Description of errors

4. Explanation of errors

5. Evaluation of errors.

Collection of a Sample of Learner Language

The first point in error analysis is the collection of a sample of learner language. Researchers have identified three broad types of error analysis according to the size of the sample. These types are: massive, specific and incidental samples. All of them are relevant in the corpus collection but the relative utility and proficiency of each varies in relation to the main goal. In other words, in this first step, the researcher has to be aware of his research, and the main objective of this stage is selecting a proper collection system.

The first type of sample mentioned involves collecting several samples of language use from a large number of learners in order to compile a comprehensive list of errors, representative of the entire population. A specific sample consists of one sample of language used, collected from a limited number of learners.

Finally, an incidental sample uses only one sample of language provided to a single learner. In practice, the most common samples used by researchers are specific and incidental in order to avoid the difficult task of processing, organizing and evaluating the large quantities of samples taken in a massive sample collection.

Identification of Errors

Once a corpus of learner language has been collected, the errors have to be identified. Therefore, it is necessary to know how to identify them. Indeed, the identification of errors depends on four crucial questions. The first question is to set up what target language should be used as the point of evaluation for the study.

The second is related to the differences between "errors" and "mistakes or slips". An error is made when the deviation arises as a result of lack of knowledge while a mistake or slip occurs when learners fail to perform to their competence in the target language. Normally, a mistake or slip is immediately corrected by the learner.

The third question is about interpretation. There are two kinds of interpretation: overt and covert. The former is easy to identify because there is a clear deviation in form (She selled her car) and the latter occurs in utterances that are syntactically and semantically well-formed but pragmatically odd (Where do you go?). The fourth question is focused on deviations. There are two kinds of deviation: correctness and appropriateness.

Their difference is very simple: the first is a deviation of the rules of the language usage (I did ate with her) and the other is a deviation of the language use (she can to do whatever she wants).

Description of Errors

The description of learner errors involves a comparison of the learner's idiosyncratic utterances with a reconstruction of those utterances in the target language. Researchers propose that there are two descriptive taxonomies of errors: linguistic categories and surface strategy.

Linguistic categories are associated with a traditional error analysis undertaken for pedagogic purposes; they can be chosen to correspond closely to those found in structural syllabi and language text books. This type of description allows a detailed description of specific errors and also for a quantification of a corpus of errors.

Linguistic categories, as Richards says (1971), state that learners' errors were the result of L1 interference.

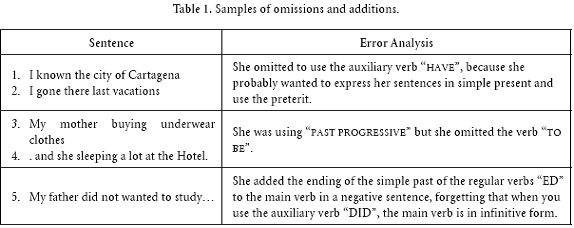

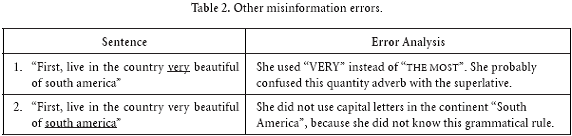

From another point of view, surface strategy taxonomy highlights the ways in which surface structures are altered by means of such operations as omissions, additions, misinformations and misorderings. Omission is considered as the absence of an item that should appear in a well-formed utterance (He cooking); addition is defined as the presence of an item that should not appear in well-former utterance (She doesn't works at hospital); misinformation is the use of the wrong form of the morpheme or structure (The chair was maked by the carpenter) and finally misordering is regarded as the incorrect placement of a morpheme or group of morphemes in an utterance (What is doing my mother?).

Explanation of Errors

There are two main positions on the source of errors in foreign language learning. One holds that errors are due to interference from the mother tongue. The other, the "creative construction" theory, proposes that the processes used in acquiring a first and a foreign language are identical and that foreign language learners' errors will resemble those of a child learning the language as his mother tongue. A third possibility is that at least some errors can be related neither to L1 interference nor to L2 developmental strategies. It has been proposed by Corder (1967) that language learners develop inter-language grammars, idiosyncratic dialects or approximate systems, and that errors will not necessarily be based on either the mother tongue or the target language.

These views do not need to be incompatible. In particular, inter-language systems might involve errors based on L1, L2 and other forms. However, a strong view of the creative construction theory, as maintained by Dulay & Burt (1972; 1974) holds that, in children below puberty who are learning a foreign language, almost all errors will be developmental. In support of this position, they found that only 4.7% of their child subjects' errors were due to interference, while 87.1% were developmental and the rest were "unique" (Dulay & Burt, 1974). A weaker view of either of the two main positions, outlined above, would still, presumably, predict something about the proportion of errors to be expected from each source: if errors are due mainly to interference, one would expect more interference errors but if they are due mainly to developmental strategies, a majority of developmental errors should occur.

In error analysis, a difficulty arises in trying to assign source of error, especially as many errors seem to have multiple origins. Developmental errors are those which resemble forms produced by children learning the language in question as their mother tongue. For example, many learners of ESL will produce "the king food" instead of "the king's food", where the absence of possessive /-'s/ is not due to interference but occurs in the speech of children learning English as their first language.

Interference errors are ones which clearly reflect interference from L1, for instance, forms such as "I have hunger" produced by speakers whose source language is French or Spanish. Dulay & Burt (1974) class as ambiguous errors which might be due to either source, such as "Jose no wanna go", which, when produced by a Spanish speaker, could be either interference or developmental. Unfortunately there appears to be no way, at present, to decide which source is operating in such cases or whether both are.

A further problem occurs in trying to analyze inter-language errors, by which I mean those not due to L1 or L2. Indeed, as Frith (1975) points out, it is very difficult to discover what the proponents of interlanguage systems consider to be the characteristics of such systems. It is not clear what they would describe as interlanguage errors, whether they would expect such errors to be systematic or idiosyntactic and what proportion of them might be expected.

Because of such difficulties with error analysis, some researchers (Krashen & Pon, 1975) have abandoned altogether the attempt to find sources of errors. Assuming, however, that analysis by source is still possible, it would be interesting to find out how adults perform as regards error production. If the creative construction theory is correct, should adults also be expected to produce a high proportion of developmental errors?

This study was undertaken partly to find out what proportion of adults' errors would be developmental, assuming (from observations on teaching adults) that a greater proportion than 4.7% would prove to be interference errors, and to see if any common inter-language forms would occur.

Other people who have analyzed adult errors have found both developmental and interference errors arise. Taylor (1975) suggests that beginners may have to rely more on their source language in formulating hypotheses about the target language grammar, whereas more advanced students could be expected to have reached a stage where they are capable of making generalizations based on the target language itself. He found that beginners made more interference errors than intermediate students. The fact that students may use different learning strategies at different stages of acquiring a language could have implications for language teaching and it would be useful to know if there are similar differences between intermediate and advanced students, a point studied by Krashen & Pon (1975).

It is also possible that sources of errors are relevant for studies of the ability to correct errors. Krashen & Pon (1975) found that an adult advanced ESL student could correct 95% of his/her errors (mistakes) immediately after production if utterances containing the mistakes were presented to him/her. Krashen (1975) proposes that adult learners acquire language in ways similar to children (naturally) and that they also learn language more consciously as a result of more formal teaching methods. What they learn is used to monitor their language production, given situations where they have occasion to monitor, such as in written work as opposed to informal conversation.

Where monitoring is not possible, the errors that occur tend to be developmental (i.e. related to acquisition). This suggests a need to find out whether this implies that developmental errors are actually harder to monitor than those from other sources.

The problems of ascribing errors to different sources have already been mentioned. Even if one can definitely describe an error as due to interference, there may still be difficulties in deciding whether the interference is phonological, syntactic or semantic. Error corrections may be useful in determining the precise form of interference, for instance in deciding between phonological and syntactic origins.

This is crucial for the creative construction theory, which refers to syntactic errors when it claims that most errors will be developmental. An error due to phonological interference is not considered a counter-argument to the theory.

One error which is common amongst Spanish learners of English occurs in the structure: pronoun -be - X, where the subject pronoun is omitted, to give forms such as:

Is crazy too

Is the man's mop

Is washing the floor

Most commonly, the omitted pronoun is "it" but it may also be "he", "she" or "they".

Cancino, Rosansky & Schumann (1975) suggest that in the case of "it" omission the interference is probably phonological. They reject the idea that it is due to syntactic interference from Spanish which allows a subject NP to be omitted, given a clear context. Instead, they suggest that it may arise because in Spanish "It's X" would be expressed as "Es X", with phonological similarity leading Spanish speakers to say "Is X" instead of "It's" in English. As evidence, they show that subjects produce "is" instead of "it's" in imitation tasks, and when they asked their subjects orally to correct sentences of the form "Is X", they would insert "he" or "she" if possible but would otherwise repeat the same form; for example, they would give "Is a book" as a correction of "Is a book", as though they thought that they had in fact made a correction. Evidence from written, rather than spoken, error corrections may help to clarify this issue. There are, then, several problems in the field of adult foreign language learning as far as error analysis and error correction are concerned. The present study seeks to follow up some of the issues raised by previous investigations in this area and to suggest further research.

Evaluating Errors

Error evaluation studies proliferated in the late 1970s and in the 1980s, motivated quite explicitly by a desire to improve language pedagogy. In these studies, judgments were based on three basic categories: comprehensibility, seriousness and naturalness of the grammar and the lexis. In this judgment process, judges have to keep in mind that there are two kinds of errors: global and local. Global error is the error which affects overall sentence organization (my house beautiful red), and local error is the error which affects single elements in a sentence (I want an hot dog).

The evaluation of learner error poses a great number of problems. It is not clear what criteria judges have used when asked to assess the categories of an error. Indeed, error evaluation is influenced by the context in which the errors occurred.

The Study

Based on the above literature, errors produced by a foreign language learner in her acquisition process will be analyzed identifying their possible producers. Then, the research methodology is presented, and in the results, as will be seen afterwards, four kinds of errors are classified. They are:

omission, addition, misinformation, and misordering.

Objectives

General Objective: To analyze the errors produced by a foreign language learner in her acquisition process.

Specific Objective

-To identify the errors produced by a foreign language learner.

- To describe the errors produced by a foreign language learner.

- To explain the errors produced by a foreign language learner.

- To evaluate the errors produced by a foreign language learner.

Methodology

The subject is a Spanish-speaking student from Colombia who is studying at a public university in Antioquia, Colombia. She has been studying English in the above university for five months. She passed English 1 level with a grade of 4.0. This course was taken at the university this year with a different teacher. Currently, she is finishing English 2 level. In her English class, there are only eight students. All of them are Colombians and none speaks English fluently. This research is a case study. Yin (2003, p. 13) defines a case as "an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its reallife context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident". He then adds: "In other words, you would use the case-study method because you deliberately wanted to cover contextual conditions believing that they might be highly pertinent to your phenomenon of study".

The student was assessed using the clinical elicitation method (CE). Corder (1981, p. 29) states that: "The CE requires the learner to produce any voluntary data orally or in writing, while experimental methods use special tools to elicit data containing specific linguistic items". The CE method involves getting the informant to produce data of any sort, for example, by means of a general interview or by asking the learner to write a composition. During the study, the learner wrote a composition entitled "My Life in Colombia" where she was able to use simple present, simple past and present perfect, which are the tense formation topics studied in English levels I and II. Their description was based on surface strategy taxonomy due to the fact that I focused on omissions, additions, misinformations and misorderings. I also kept in mind overt and covert errors and possible learner deviations related to correctness and appropriateness. Erika's errors also were analyzed in terms of whether they were due to interference from Spanish or to developmental strategies.

This sample took place two weeks after she wrote this composition. She was given as much time as she needed to make corrections before I checked it. The main goal was to identify how many errors she really wrote and which of them were only mistakes or slips (performance).

The Results

As I said above, the student was assessed using the clinical elicitation method (CE), using a personalized composition.

Corder (1973) classifies errors in terms of the difference between the learner's utterance and the reconstructed version and proposes four different categories:

omissions, additions, misinformations and misordering. The presentation of the error analysis is developed in the following way:

1. Firstly, introduction of the strategy taxonomy of the error.

2. Secondly, a specific example of the error taxonomy presented in Erika's composition.

3. Thirdly, error analysis. 4. Finally, other errors made by Erika in her composition, classified in the same strategy taxonomy.

Omission

"First, live in the country very beautiful of south america"

In the underlined part of this sentence, Erika omitted the subject pronoun "I" before the verb, as a result of the Spanish influence since in this language people normally use tacit subject pronouns. As mentioned, omission is considered to be the absence of an item that should appear in a well-formed utterance. In this sample, L1 verbal conjugation influenced Erika's L2 grammatical structures, affecting directly the rules and modifying the usages of L2 grammar categories. Based on Spratt et al. (2005, p. 44), this indicates interference.

The authors point out that "an interference or transfer is an influence from the learner's first language (L1) on the second language".

Other omission errors are presented in Table 1.

Additions

"I am study Administration"

In the underlined part of this sentence, Erika added the verb to be to a present simple sentence because she probably assumes that the verb to be has to be in all the sentences. As outlined earlier, addition is considered to be the presence of an item that should not appear in a well-formed utterance. This error was unconsciously made, because her learning process has just started and she had been working out how to organize the elements that comprise L2. As can be seen, her process was not yet complete. This kind of error is called developmental error (Spratt et al, 2005).

Misinformation

"I known the city of Cartagena there the clime is hot"

In the underlined part of this sentence, Erika used two incorrect forms. The first one is "there" instead of "where" and the second one is "clime" instead of "weather".

These errors are the result of the lack of English vocabulary, and the wrong use of the meanings provided by the dictionary.

On the other hand, we should also remember that misinformation is considered to be the use of the wrong form of the morpheme or structure. This same example could have another interpretation and on equally convincing explanation. In other words, the learner's perlocutive act could be different, possibly she meant to say: "I know the city of Cartagena. There the weather is hot", but she was not aware of the correct English punctuation and this misinformation, added to vocabulary problems, changed the sentence meaning. In this case, the word "clime" meets interference error requirements, and becomes a false cognate.

Other misinformation errors are

shown in Table 2:

Misordering

"First, live in the country very beautiful of south america"

In the underlined part of this sentence, Erika incorrectly ordered the words in this sentence. The correct syntactical order was "… in the most beautiful country of South America". In connection to this, we should bear in mind that misordering is considered to be the incorrect placement of a morpheme or group of morphemes in an utterance. In addition, misinformation is present in the sample above. This is evidenced in the use of "very" instead of "the most". In this case, L1 syntax influenced Erika's L2 grammatical structures, modifying the position of L2 grammar categories, affecting meaning, and indicating interference.

On the other hand, the student composition makes us realize that it is important to keep in mind overt and covert errors and possible learner deviations related to correctness and appropriateness.

Overt and Covert Errors

In Erika's composition all her errors were overt. An overt error is a clear deviation in form; for example:

1. My father did not wanted to study…

2. I known the city of Cartagena 3. I gone there last vacations

4. My mother buying underwear clothes

5. … and she sleeping a lot at the Hotel.

Erika's composition did not have covert errors due to the fact that the wellformed sentences meant that she expressed her ideas appropriately, according to the context. Finally, Erika's errors were also analyzed in terms of whether they were due to interference from Spanish, due to developmental strategies.

Interference and Developmental

Burt (1974) classified errors collected into three broad categories:

a. Developmental (i.e. those errors that are similar to L1 acquisition).

b. Interference (i.e. those errors that reflect the structure of the L1).

c. Unique (i.e. those errors that are neither developmental nor interference).

I present some samples taken from Erika's written composition and which are classified in two main categories: developmental and interference (see Table 3). As can be seen in the table, the composition does not have a "unique" error type. Additionally, the samples evidence the learner's will to get the message across.

Conclusions

Learning a foreign language demands not only willingness, but also practice and commitment by both learner and teacher.

That's why, indisputably, error analysis is a fundamental and relevant tool in language teaching, in order to reorganize and transform the teacher's point of view and readdress his/her methodology, with the aim of fixing and filling the students' gaps.

When a teacher realizes the nature of his/her students' errors and their possible sources, s/he can make better decisions, which will positively affect his/her performance and fulfill current pedagogical and professional demands.

In addition, the work of error analysis theoreticians (Burt et al, 1973; Cancino et al, 1975) who focused on collecting, categorizing and analyzing students' errors, has been developed and has shown teachers how they can apply theory in the development of their courses (Cohen, 1990; Schulz, 1991; Spratt et al, 2005). As far as error analysis, in some cases, its category divisions are not so precise, because they can be placed in different options due to the fact that a lot of sources appear as possible influences in an error.

Therefore, multiple explanations could possibly appear in an error analysis process, and socio-cultural context also has a valid role. In other words, L1 affects the L2 learning process not only syntactically, but also meaningfully. Prior knowledge (Ausubel, 1963) and cultural background (Canale & Swain, 1980) are two important elements in a foreign language learning process, and both appear in developmental and interference errors.

In this study, the use of category and surface strategy taxonomy facilitated Erika's written composition classification and analyses and became a great tool in error analysis. In other words, omission, additions, misinformation and misordering were identified in some cases in the corpus. Other errors were related to Spanish interference.

The experience described in this paper tells us that error analysis supports the purpose of language teaching. It can also contribute to changes in students' awareness of errors, lead to the acquiring of extra knowledge, and help them gain communicative expertise. By making students conscious of errors, we can also contribute to cognitive processes and to other changes that teaching can bring about.

Indeed, the process of language learning depends on the decisions and involvement of the students, based on their experience of life and of language as individuals. A better understanding of the learner can help the teacher understand what elements are playing a role in the students' learning process. Likewise, by analyzing and recognizing students' errors we may come to value the fact that errors are the most significant evidence of their efforts to follow the path of the learning process.

References

Ausubel, D.P. (1963). The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. New York: Grune & Stratton. [ Links ]

Burt, M.K., Dulay, H.C., & Hernandez, E. (1973). [ Links ]

Bilingual syntax measure. New York: Ed. Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch. [ Links ]

Canale, M., & M, Swain. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied linguistics. London, Longman. [ Links ]

Cancino, H., Rosansky, E. J., & Schumann, J. H. (1975). Testing hypotheses about second language acquisition: The copula and negative in three subjects. Working Paper on Bilingualism, 3, 80-96. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. (1990). Language learning: Insights for learners, teachers, and researchers. New york: Newbury House/Harper Row. [ Links ]

Corder, S. P. (1981). Error analysis and interlanguages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Corder, S. P. (1973). Introducing applied linguistics. Middlesex: Penguin. [ Links ]

Corder, S. P. (1971). Idiosyncratic dialects and error analysis. IRAL 9(2), 147-160. [ Links ]

Corder, S. P. (1967). The significance of learners' errors. Reprinted in J.C. Richards (ed.) (1974, 1984) Error Analysis: Perspectives on second language acquisition, pp. 19-27. [Originally in International Review of Applied Linguistics, 5(4)] London: Longman. [ Links ]

Dulay, H. C., & Burt, M. K. (1974). Natural sequences in child second language adquisition. Language Learning, 24(1), 37-53. [ Links ]

Dulay, H.C., & Burt, M.K. (1972). Error analysis: Perspectives on second language acquisition. London: Longman. [ Links ]

Frith, M.B. (1975). Second language learning: An examination of two hypotheses. IRAL, 13(4), 327-332. [ Links ]

Krashen, S. (1975). A model of adult second language acquisition. Paper presented at LSA. [ Links ]

Krashen, S., & Pon, P. (1975). An error analysis of an advanced ESL learner: The importance of the Monitor. Working Papers on Bilingualism, 7, 125-129. [ Links ]

Richards, J.C. (1971). Error analysis and second language strategies. Language Sciences, 17, 12-22. [ Links ]

Schulz, R. (1991). Second language acquisition theories and teaching practice: How do they fit? The Modern Language Journal, 75(1), 17-26. [ Links ]

Spratt, M., et al. (2005). The teaching knowledge test course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Taylor, B. P. (1975). Adult language learning strategies and their pedagogical implications. TESOL Quarterly, 9, 391-399. [ Links ]

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: sage. [ Links ]